Abstract

As the first modelling environment, family represents a resource of visible and invisible, explicit and implicit, transparent and insinuated, persuasive, manipulative or convincing influences. As a source for the mental images that activate and adjust the attitudes of students towards learning school, family remains a bidder territory for investigation. The association between academic achievement and the myriad of potential variables visible and invisible it is a challenge assumed by many researches. The parenting as source for the mental images that activate and adjust some attitudes of students towards learning school remains a bidder territory for investigation. The paper is focused on the interpretation the academic achievement relative to a set of parents’ scenarios transmitted and internalized by the child as a set of beliefs that nourish, directly and indirectly, his attitude towards learning. An attitudes towards school possible trans-generational model. It was used a questionnaire which tried to capture details on issues such as: the evaluation (made by the pupils) of parents involvement in school activities, the pupils’ image on the importance that parents attribute to school and school career, the pupil’s adhesion to thematic statements. Number of participants: 140 pupils of gymnasia level. The data indicate statistically significant correlation between pupil’s academic achievement and parental internalized messages and attitudes.

Keywords: School learningfamilial curriculumparental modelbeliefs“earning attitude

Introduction

The level of children’s school achievement is a result of an interaction between numerous factors. This interactions can be a convergent or a conflictual. In first case, the result are the desired ones, in second the problems appear. Research has positioned the school results in relation with variables which belong to the school environment or non-school environment, in relation with variables which depend by pupils or not. The sources of these beliefs are the engagement of parents in learning activity, engagement expressed not only in a verbal way, but in an active one. Parents’ beliefs do not necessarily have to be explicit. Often subtle aspects of beliefs and behaviour can be very influential (Bempechat, 1992). As representative adults, parents impregnates family environment with their own culture relating to child's school experience. This culture is a significant landmark for adjusting expectations regarding learning. Walberg (1984) proposed the expression ”curriculum at home” that predicts academic learning twice as well as the socioeconomic status of families (Walberg, 1984, p. 397). Curriculum at home includes “informed parent/child conversation about everyday events, encouragement and discussion of leisure reading, monitoring and join analysis of tele viewing, deferral of immediate gratifications to accomplish long-term goals, expressions of affection and interest in children’s academic and personal growth” (Redding, 1992, p. 63)

Problem Statement

One of the main arguments for constructing school performance indicators is that raw, unadjusted results are influenced by factors beyond the schools' control. Farooq, Chaudhry, Shafiq, and Berhanu (2011) inventory numerous researches on the factors that influence the quality academic achievement .Educators, trainers, and researchers have long been interested in exploring variables contributing effectively for quality of achievement of learners. These variables are inside and outside the school that affect students’ academic achievement. All of the research reviews support the hypothesis that student performance depends on different socio-economic, psychological, environmental factors. Pupil composition is maybe the most important of such external factors (Hægeland & Kirkebøen, 2008). School performance indicators may be affected by differences in how socioeconomic status (SES) variables and prior attainment is controlled for. In terms of explaining individual variation in pupil attainment, parental education is by far the most important set of SES variables. It also matters how parental education is included in the model. Socioeconomic status (SES) is one of the most researched and debated factor among educational professionals that contribute towards the academic performance of students (Habibullah & Ashraf, 2013; Quaiku & Boateng, 2015).

The study of Wenglinsky (2001) produces three MSEMs (multilevel structural equation modelling). The first MSEM relates teacher inputs to student academic performance, taking into account student socioeconomic status (SES) and class size. SES (Students Family Gets Newspaper, Students Family Has Encyclopedia, Students Family Gets Magazine, Students Family Has More than 25 Books, Fathers Education Level, Mothers Education Level) has an effect size of .76, which far overshadows those of class size and teachers major (.10 and .09, respectively).

In his Theory of Educational Productivity, Walberg (1981) determined three groups of nine factors based on affective, cognitive and behavioural skills for optimization of learning that affect the quality of academic performance: Aptitude (ability, development and motivation); instruction (amount and quality); environment (home, classroom, peers and television)

The home environment affects the academic achievement of students. Educated parents can provide such an environment that suits best for academic success of their children. The school authorities can provide counselling and guidance to parents for creating positive home environment for improvement in students’ quality of work (Marzano, 2003). Coleman’s large scale study of the factors that influence academic achievement showed a stringer correlation between achievement and family background and environment that between achievement and the quality of the school (Colemen, Campbell, Hobson, McPartland, Mood, Weinfeld, & York, 1966).

The literature distinguished between cognitive socialization – how parents influence the basic intellectual development for their children, and the academic socialization – how parents influence the development of attitudes and motives that are essential for the school learning (Baker & Stevenson, 1986; Milne, Myers, Rosenthal & Ginsburg, 1986; Stevenson & Baker, 1987).

A considerable amount of research evidence is converging to show that parents’ attitudes, expectancies, and beliefs about schooling and learning guide their behaviour with their children and have a causal influence on the children’s development of achievement attitudes and behaviours (Ames & Archer, 1987; Bempechat & Wells, 1989; Eccles, 1983; Entwisle & Hayduk, 1988; Epstein, 1989; Fehrmann, Keith, & Reimers, 1987; Marjoribanks, 1979).

Epstein (1989) develops a TARGET model of academic socialization: six interrelated dimensions of the home environment that are conducive to academic achievement. That six dimensions are: task structure (the variety of home activities in which children are involved), authority structure (the level of children’s autonomy and their participation in family decision-making), reward structure (the ways in which parents recognize and valorise the advance in learning), grouping structure (the impact of parents for children’s social interaction with peers and family members), evaluation structure (the set of criterion and standards that parents use for judging the school performance), time structure (how parent manage children’s time).

Research Questions

Do children receives and internalize the parents’ behaviours and messages regarding school learning, investing them as a reference models and practicing them in their school learning attitudes?

Purpose of the Study

The paper proposes to analyse some rather invisible variables: the pupils’ beliefs about the importance of school learning, in their quality as potential results of parents’ messages.

Research Methods

The method used for data collection was a questionnaire which tried to capture details on issues such as:

- the engagement of parents in school activities: check school attendance, verify homework, verify learning achievement, encourage children in their learning efforts; (answers were positioned on a five-point scale: always, often, sometimes, rarely, never),

- the importance that parents recognize the school has,

- the pupils’ beliefs (eg the school is only useful for those who want go to faculty, the way in which my parents perform as pupils is a model, children should continue school even if their parents gave up early, etc.) (the answers were positioned on a five-point scale: strongly agree, rather agree, neither agree nor disagree, rather disagree, strongly disagree).

The answers were analysed on two dimensions: parents’ engagement and the pupils’ beliefs. For the first dimension were used 7 statements (initially, 9 statements were formulated, but to improve the reliability, two were eliminated), and for the second dimension were formulated 12 statements. The reliability for the first dimension was good (the value of Cronbach's alpha=.779). For the second dimension the value of Cronbach's alpha was .816, which means a good reliability, too.

In this investigation were involved 140 lower secondary school pupils (grades 5th, 6th and 7th): 40 pupils of 5th grade, 50 pupils of 6th and 50 pupils of 7th grades. The distribution was made based on two criteria: the level of school academic achievement (good students or weak students) and schooling environment (urban or rural). For create the group of subjects was used the analysis of school documents. Thus, based on the school learning situation registered in catalogues, were identified best two or three pupils in each classroom, and two or three pupils who are in academic risk (in some classes there was only one nomination, in other even five nominations). This was the mechanism for generating labels used "good student", "bad student".

The data were processed using IBM SPSS 19 software.

Findings

Dimension Parents engagement

Checking school attendance. 58.57% of the answers express the agreement on the importance that parents provide for school attendance, while almost 20% (19.29%) of the answers express the disagreement. Relation between the two variables is confirmed by statistical correlation coefficient 0.324, significant at a 0.01 level: the parents of good pupils show more interest for the presence / absence of children in school activities, compared to parents of students with poor school performance. In relation to environmental criteria, rural good pupils’ parents have obtained an average slightly higher compared with urban ones; instead, the average of the weak pupils’ parents from urban is higher than that obtained by the parents of the weak pupils from rural areas. In other words, relative to check the frequency of participation to school program, parents from urban areas show a higher commitment than parents in rural areas.

Verify homework. The behaviour surprised in the statement is performed by more than half of the parents of the questioned students: 58.57% of the answers express the agreement; only 18.15% of students recognize the absence or rather absence of parental behaviour. Although a statistically significant correlation is found (0.214 at a significance level of 0.05), it has a low intensity. However, allows the observation that students with good academic results say their homework are verified more often than students with poor school performance. A proof that parents the of good pupils value the home learning experiences more than parents of low achievers. Associated with environmental criteria, the data show that parents of good students from rural areas are more interested by homework compared with parents of pupils with similar results from urban areas. Possibly due to more free time compared to parents in urban areas.

Verify school learning results. Verifying school outcomes is a highly practiced behaviour by parents: 73.57% of students meet it in the family environment. The correlation between the two variables is 0.396 at a significance level of 0.01: parents of the pupils with good results is are more interested the school results compared the parents of weak pupils. Good pupils from urban areas said in a slightly greater extent that their parents are interested in school performance.

Provides encouragement regarding learning effort. Half of the surveyed students (51.33%) experience parental encouragement in their learning activity, while almost 31.53% of the answers express the disagreement Data indicate a significant difference at this level between pupils’ responses: to offer encouragement attitude is characteristic for parents of children with good academic results. Coefficient of correlation is significant: 0.517 at 0.01 level. Good pupils from urban areas said in a slightly greater extent that their parents encourage them in school activities.

Dimension Beliefs

The school is essential for my future. 56.43% of answers confirms the critical importance that parents invest in the experience of the school in relation to children's future. A quarter of the answers does not confirm this importance. The message about the importance of school makes the difference between pupils: successful pupils recognize the essential role that the school plays. The value of correlation coefficient confirms it: 0.748 at a significance level of 0.01.

The data obtained are confirmed by another one, regarding the belief "my parents believe that are more important things than school". Regarding the existence of other more important things compared to the school, 34.86% of the students receive confirmatory messages from the parents, 44.29% of students receive opposite answers. Thus, good students expresses the reality that their parents value the school more than anything else; but not the weak students. Correlation coefficient has a value of (-)0.722 at a significance level of 0.01. There is a poor correlation of the answers given in relation with ”environment” variable:

-0.179 (at the 0.05 level). The difference between the scores for the variable "meaning school for the future" generates a possible interpretation: pupils add their own spore in school valorisation. In other words, when parents affirm the importance of school, children's reaction is to amplify this meaning

Shaping force of parental example is captured by the variable "Children need to continue their studies even if their parents have abandoned them". 55.71% of students are convinced that parental abandonment is not a model to follow (noting that most of them (80%) answered "strongly agree"). Thus, by the criterion level of academic achievement, belief correlates: 0.643 (significance level 0.01). Pupils with high school results show more optimism. They say that should ignore the negative model of parent schooling. Pupils with poor results remain fixed in the parental’ model inertia.

The belief that school is useful only for those who intend to continue the university studies characterizes 77.8% of the students involved in the investigation. The interest shown by parents is a nutritional source for pupils’ school learning motivation. 83.56% of students recognize the effect of such parental attitude. The correlation of 0.171 (significance level 0.05) is not a strong one, but tend to confirms a reality: pupils with good academic results tend to recognize the importance of parental attitudes, in opposition to students with poor results. The difference between the two categories of pupils was made not by the means, but the standard deviation:

An interesting variable is related to the belief that a valid solution for coping in life is to work early (to start early to work). Half of responses agree the idea, a quart of them not. This variable is statistically significantly correlated both variable level of academic achievement (0.376 at a significance level of 0.01) and the environment variable (0.421 at a significance level of 0.01). For students with poor school results, early work represents an important alternative. Pupils from rural areas value the early onset of work more than urban students. The environment correlates more intense than achievement level. In other words, for students from rural and poor results an earlier job is a more reliable solution. The socio-economic situation of rural areas is a source of motivation for children to think work as a solution.

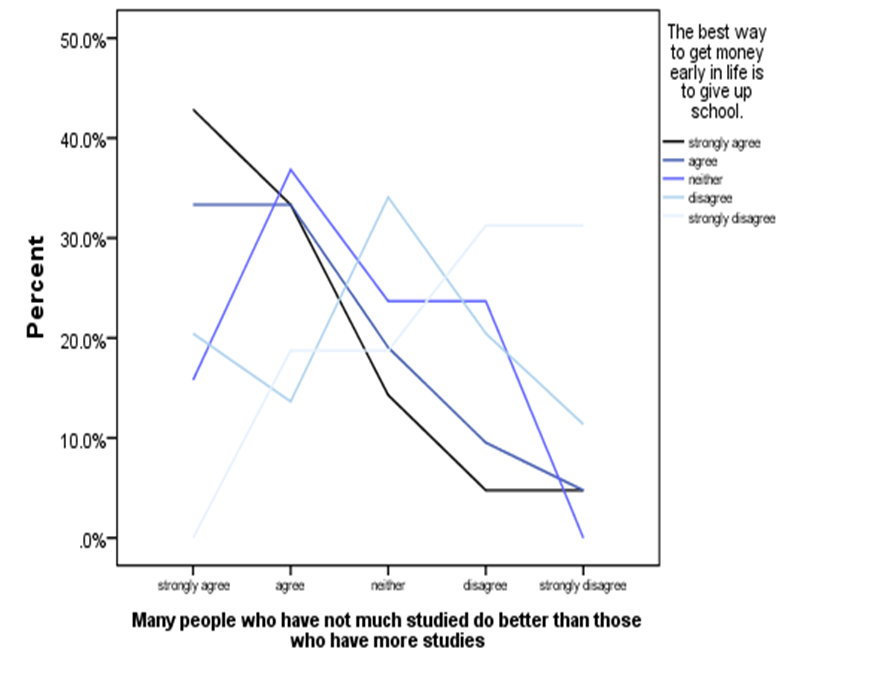

The above information in Figure

For pupils with poor results, a model of impact is those who although not many studies do better than those who have a long school career.

An interesting crosstabulation can be made on basis the answers at "Many people without education are better than those educated" and "Quitting school is the best way to get money early in life" (the correlation is 0.394 at 0.01 level). Pupils who agrees with school dropout are those who are convinced that many of those with no education are more successful in life (see Figure

Conclusion

The data allow some relevant conclusions. On the one hand, the way in which children receives and evaluates parental involvement in school learning activity is associated with the level of school performing as a student. Students with good school results are those who recognize that their parents show a greater involvement. This attitude of parents communicates pupils the importance of school experience. A message that has force to feed and adjust learning efforts. A message that shape pro-school beliefs and attitudes. Complementing this set of variables are those relating to most elaborate messages on the significance of school and especially to adhesions or distances expressed by the children in relation to them. Can be noticed that students with poor academic results are more adhesives on anti-school beliefs expressed by parents. Thus, it can be said that parents create by their attitude a scenario that children tend to perpetuate it. Even it was not under investigation, a conclusion with hypothesis value is requires: for children learning attitudes the belief expressed by parents have a higher modelling strength than they performing in past as pupils. Although the environment is not a variable that correlates to the same extent, he adds interesting social shades. Through their own system of values, the family provides the child with an axiological curriculum capable of shaping attitudes in relation to significant life experiences. The family builds a skeleton of behavioral landmarks (considered as significant) that it transmits both verbally and nonverbally, both intentionally and unintentionally, both transparently and insinuated. Children not only accept, but also react to these messages. But although they often filter this response, in their attitude to school, parents' messages have a strong modeling force.

References

- Ames, C., & Archer, J. (1987). Mothers’ beliefs about the role of ability and effort in school learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 71, 409-419.

- Baker, H., & Stevenson, D. (1986). Mothers’ strategies for children’s school achievement: Managing the transition to high school. Sociology of Education, 59, 156-166.

- Bempechat, J., & Wells, S. (1989). Promoting the achievement of at-risk students. In Kronick, R.F. (ed.) (1997). At-Risk Youth. Theory, Practice, Reform. New York: Routledge

- Bempechat, J. (1992). The role of parent involvement in children’s academic achievement. The School Community Journal, 2(2), 31-41. Retrieved from http://www.adi.org/journal/fw92/BempechatFall1992.pdf

- Coleman, J., Campbell, E., Hobson, C., McPartland, J., Mood, A., Weinfeld, F, & York, R. (1966). Equality of educational opportunity. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office

- Eccles, J. (1983). Expectancies, values, and academic bahaviors. In Spence, J. (Ed.) Achievement and achievement motives: Psychological and social approaches. New York: Freeman

- Entwisle, D., & Hayduk, L. (1988). Lasting effects of elementary school. Sociology of Education, 61, 147-159.

- Epstein, J. (1989). Family structures and student motivation: A developmental perspective. In Ames, C., & Ames, R. (Eds.) Research on motivation in education 3: goals and cognition. San Diego, C.A.: Academic Press, 259-295.

- Farooq, M.S., Chaudhry, A.H., Shafiq, M., & Berhanu, G.B. (2011). Factors affecting students’ quality of academic performance: a case of secondary school level. Journal of Quality and Technology Management, VII (II), 1-14. Retrieved from http://pu.edu.pk/images/journal/iqtm/PDF-FILES/01-Factor.pdf

- Fehrmann, P., Keith, T., & Reimers, T. (1987). Home influence on school learning: direct and indirect effects of parental involvement on high school grade. Journal of Education Research, 80, 330-337

- Habibullah, S., & Ashraf, J. (2013). Factors affecting academic performance of primary school children. Pakistan Journal of Medical Research, 52(2), 47-52. Retrieved from http://www.pmrc.org.pk/PRIMARY%20SCHOOL%20CHILDREN,PJMR-2013%20(2),p47-52.pdf

- Hægeland, T., & Kirkebøen, L.J. (2008). School performance and value added indicators - what is the effect of controlling for socioeconomic background? A simple empirical illustration using Norwegian data.

- Retrieved from https://www.ssb.no/a/english/publikasjoner/pdf/doc_200808_en/doc_200808_en.pdf

- Majoribanks, K. (1979). Ethnic families and children’s achievement. Sydney: Allen & Unwin

- Marzano, R.J. (2003). What works in schools: Translating research into action. Alexandria: Association for Supervision & Curriculum Development

- Milne, A., Myers, D., Rosenthal, A., & Ginsburg, A. (1986). Single parents, working mothers, and the educational achievement of school children. Sociology of Education, 59(3), 125-139.

- Quaiku, W., & Boateng, K. (2015). Investigating Stakeholders’ Involvement. Quality Basic Education Delivery. The International Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities Invention, 2(8), 1515-1524.

- Redding, S. (1992). Family Values, the Curriculum of the Home, and the Educational Productivity. The School Community Journal, 2(1), 62-69. Retrieved from http://www.adi.org/journal/ss92/reddingspring1992.pdf

- Stevenson, D., & Baker, D. (1987). The family-school relation and the child’s school performance. Child Develoopment, 58, 1348-1357.

- Walberg, H. J. (1981). A psychological theory of educational productivity. In Farley, F.H., & Gordon, N. (Eds.), Psychological and Education (pp. 81-110). Chicago: National Society for the Study of Education

- Walhberg, H.J. (1984). Families as partners in Educationa, Productivity, Phi Delta Kappan 65, 397-400. In

- Wenglinsky, H. (2001). Teacher Classroom Practices and Student Performance: How Schools Can Make a Difference, Statistics & Research Division. New Jersey: Princeton.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-066-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

67

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2235

Subjects

Educational strategies,teacher education, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Petre, C., & Simion*, L. (2019). Internalized Parental Messages As Source Of Children’s School Learning Attitude. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 67. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 687-694). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.03.82