Abstract

Romanian children’s participation in protests and marches held in February 2017, in all Romanian big

Keywords: Protestchildrenparticipationvaluescivic education

Introduction

The concept of political culture was firstly brought to attention by Almond and Powell (1966) who

considered that political culture of a society "consists of attitudes, beliefs, values, and skills which are

current in an entire population, as well as those special propensities and patterns which may be found within

separate parts of that population" (p. 23). Also we will consider political culture to imply an active or a

passive form of knowledge, emotions and values related to political subjects and to events that are

happening in a particular society. Dogan and Pelassy (1993) consider that the concept of political culture

"designates a set of political beliefs, feelings, and values that prevail for a nation at a certain time" (p.71).

One of the first modern studies that analyse the topic of political culture in democracy belongs to Almond

and Verba (1963) Civic Culture, Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations, (p.13) that defines

political culture as political orientations or attitudes towards the political system. These authors have

generally asserted that political culture has broad implications that affect the performance of the political

systems (Almond & Verba, 1963, p. 31-34).

As a free public manifestation of ideas, opinions, beliefs and values, the protest is considered one of

the indicators of modern democracies. It is a specific manifestation of political culture and it is an active

way for citizens to get involved in the country's governing act. Turner (1969) considers that "An act of

protest includes the following elements: the action that expresses a grievance, a conviction of wrong or

injustice; the protestors are unable to correct the condition directly by their own efforts; the action is

intended to draw attention to the grievances; the action is further meant to provoke ameliorative steps by

some target group; and the protestors depend upon some combination of sympathy and fear to move the

target group in their behalf" (p.816). Opp (2009), considers that a protest is: "1. an action or a behaviour as

a joint action; 2. the actors object to one or more decisions of a target, so the actors have at least one

common goal; 3. the actors are unable to achieve their goals by their own efforts, instead, they put pressure on targets; 4. the behaviour is not regular, it is «unconventional». An action may be «unconventional» if

there are no institutional rules prescribing that it is repeated over time" (p.34).

Related to political culture and protest, it is also the concept of political socialization process. In his

study, Greenberg (2009) defines political socialization as the procedure through which people accept the

convictions and the principles of the political system they belong to and that determines their personal roles.

This definition is built on the premise that political socialization is the learning "process by which the

individual acquires attitudes, beliefs and values relating to the political system of which he is a member and

to his own role as a citizen within that political system" (p.3). Models mediated by different agents such as

family, school, institutions and organizations, media, the entire society as a whole, are mentioned in many

studies on this topic (Easton & Dennis, 1969; Kawata, 1986; Ross, 1984; Bragaw ,1989; Shaheen, 1989;

Allen, 1989). In the

socialization as "any political, formal and informal, deliberate and unplanned learning process at any stage

of the life cycle, including not only the explicit political learning but also the non-political symbolic

learning" (p.55). This definition emphasizes that socialization is a progressive learning process in a

continuous change. It is also worth mentioning that the definition includes references to both formal

education (school) and informal elements such as media, the influence of the social group, institutions, the

politic regime and all the others social factors.

Problem Statement

In the present context, not only for Romania, but also at a worldwide level, the novelty of children

participating in public manifestation is indisputable. Thus, the presence of children participating in protests

raises a series of questions for educators, psychologists, educational and social scientists about the

suitability of their participation in civic events and about the impact it has on children’s education. This research is focused on revealing the parents’ intentions that can be identified in the children`s presence in

protests.

Research Questions

What particular social values are parents trying to promote through their children’s involvement in

protests? Our aim is to identify which specific categories related to the axiological field can be recognised

in the parents' discourse (cognitive, behavioural, attitude-evaluative, affective dimension). Thus, we intend to describe, based on the content analysis of written material, the parents’ attitudes and perceptions

regarding the values promoted through the children’s participation in protests.

Purpose of the Study

Our aim is to explore the perceptions of socially active parents regarding the values promoted

through the participation of children in protests, using as main source of information the family, who is the

main decision-maker and the one that supports their involvement in this activity. For this, we will use the

next working definition of values: "Values are explicit or implicit conceptions of what is desirable. They

are not directly observable, but involve cognitive, evaluative and emotional elements, are relatively stable

over time, they generate behaviours and attitudes, determine and are determined by other values, and the

characteristics of the social environment" (Voicu, 2010, p.261).

The variable is the value described by the following categories:

1. cognitive dimension: knowing, understanding, learning; 2. behavioural-active dimension: to

participate, to act, to make, to defend, to express, to take part; 3. attitudinal dimension: acting, believing,

sustaining; 4. affective dimension: not be afraid, to be happy, to be proud; 5. evaluative dimension: honesty

(not to steal), dignity, social justice.

This categorization also corresponds to the theoretical approach of Almond and Verba (1963) which

underlines the idea that political culture is synonymous with the frequency of the following types of

guidelines: 1. "cognitive orientation", that is, knowledge of and belief about the political system, its roles

and the incumbents of these roles, its inputs and its outputs; 2. "affective orientation" or feelings about the

political system, its roles, personnel and performance; 3. "evaluational orientation", the judgments and

opinions about political objects that typically involve the combination of value standards criteria with

information and feelings (p.15).

Research Methods

the members of on-line community.

by 80 respondents between April 30th 2017 and July 20th 2017. Among the questions related to the topic of

children’s participation in protests, we have chosen the answers to three open questions: 1.

child/children in protest? 66 answers; 2.

important for children to participate in protests, along with their parents? 60 answers; 3.

him/her/they in protests/marches that you have participated in? 59 answers.

considering the aim of the present study and the topic of our research. The answers were aggregated in a

text of 2680 words that was considered to be the unit of analysis. In the process of coding we considered

the "value" the main concept that was associated with 5 categories, described by verbal indicators. Thus,

the coding unit, or the word, in going to be our main instrument for the present analyse.

parents’ answers to the three open questions. Voyant Tools is an open-source, web-based application for

performing text analysis, such as word frequency lists, frequency distribution plots, and KWIC displays.

Findings

A brief analysis of the presence, the frequency and the distribution of the concepts in the aggregated text

applying LIWC program reveals the following features: (Table

1.LIWC ResultsDate/Time: 7 August 2018, 10:44 am, the text you submitted was 2680 words in

length.

According to the methodological theory, "The word frequency usually indicates the important

themes of the text" (Agabrian, 2006, p.23). Taking into consideration this criterion, the important themes

of the text are: children*(58), involve*(33), participate*(31). However, although the word "fear"(7), does

not indicate a high frequency in the basic text, the code is very important for the entire study at the level of

the affective dimension indicators, which justifies our decision to consider it as a significant word in the

emotional semantic category.

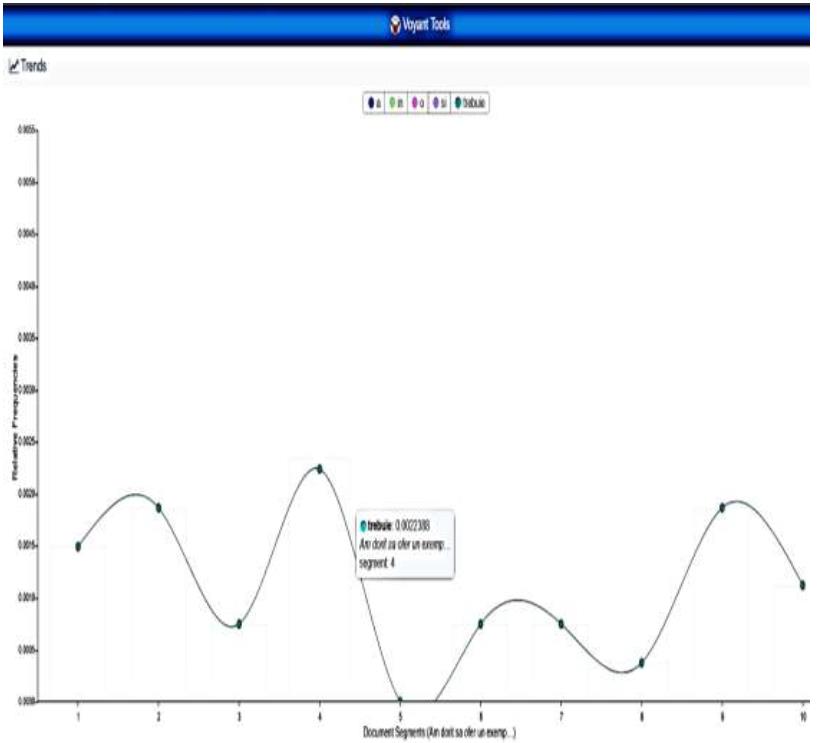

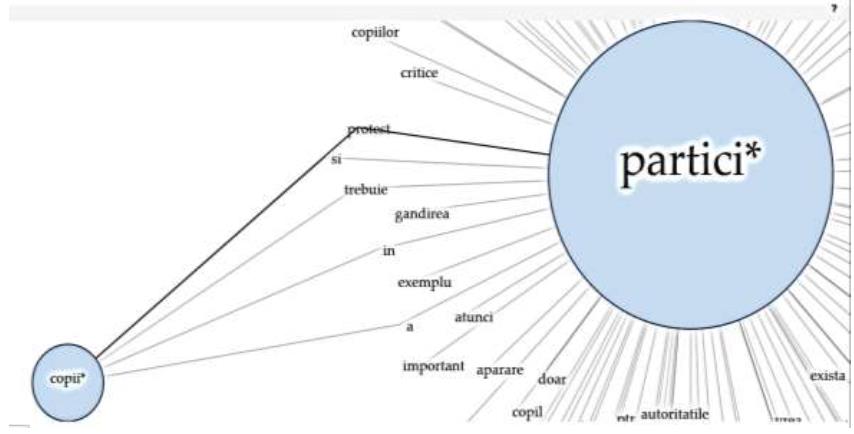

As for the frequency of the different indicators, the text analysis using the Voyant Tool Program

highlights, with the exception of the link words, that the word must*(30) has the highest frequency and a

relatively constant distribution along the text.(Figure

In terms of absolute frequency, at the level of different dimensions that contain the values

emphasized by the parents in their discourse, we can hierarchize them by the criterion of importance:

1.

"to express", "to take part" related with codes like: participate* (31), action*(13) supportive*(3),

defend*(5), conduct*(2) - total 63 indicators

2.

upheld*(10), responsible*(8), believe*(1), attitude*(1), civic*(15) - total 53 items

3.

sample*(13), value*(1), truth*(1), lie*(1), community*(11) - total 36 items

4.

learn*(10), know*(6), idea*(7), understand*(1) - total 24 units

5.

emotions*(1), feeling*(1), trust*(2) - total 11 items

Thus, we can state that the attention of the respondents focuses on sending messages that predominantly

reveal the behavioural-active dimension. The adults are urging for action, for involvement, for participation,

but they are also discussing subjects such as the values promoted and that are in accordance with the model

provided by themselves. For this interpretation there is a limit, such as the existence of indicators that could

be part of at least two dimensions: the word "protest", for example, was not included in the encoding list,

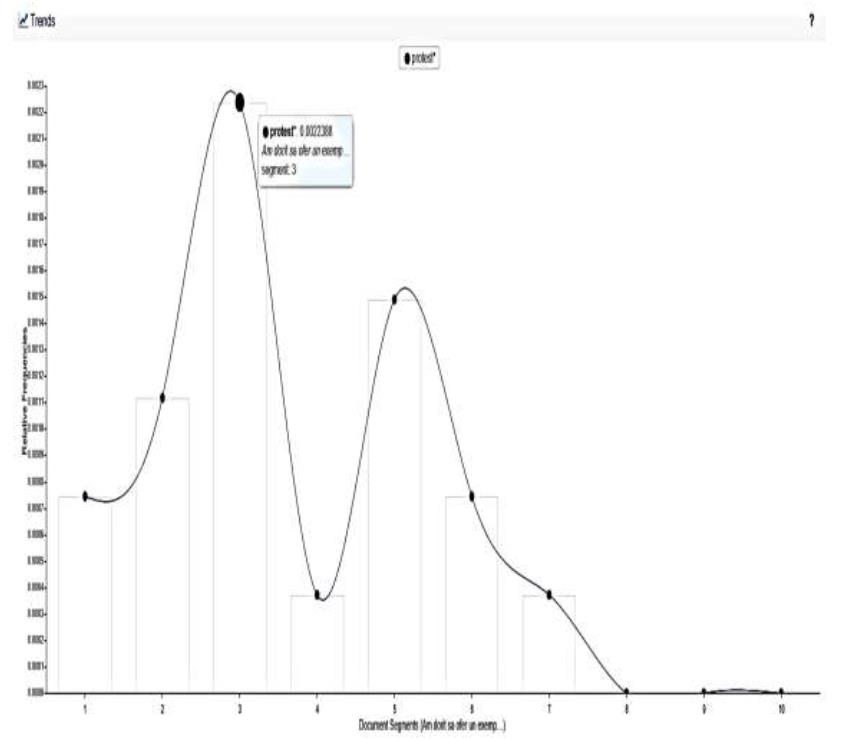

to avoid ambiguity. The word "protest" (Figure

The relational or semantic analysis based on conceptual links, examines the relationships between

concepts. In order to accomplish the proximity analysis, which is focused on the concomitant occurrence

of explicit concepts in the text, we will associate the codes two by two just to highlight the links between

the codes. We will determine a sequence of words of given length, by looking at the links between the units

of measurement and by identifying the simultaneous presence of explicit concepts in the text. The proximity

criterion that we applied over the text would have verified the concomitant presence of the concepts, thus

creating the conceptual matrix of the unit analysis (Agabrian, 2006, p.101). Frequent associations of words

in the text have led to the identification of the following proximity (words together): "a child must"(30 times), "children’s future"(13 times), "children's education"(13 times), "children’s participation"(8 times),

"children in protests" (8 times), "civic education"(7 times), "civic responsibility"(7 times), "the source of

learning"(7 times), "active implication matters"(7 times), "politic environment"(6 times), "participation in

protests" (6 times), "to promote values" (5 times), "community`s life"(5 times), "to involve children"(5

times), "the future society"(5 times), "it is a must to participate"(5 times), "the power of the example"(4

times), "the right to express"(4 times), "the participatory democracy"(3 times). Thus, the formed matrixes

or the interrelated contextual groups of concepts which suggest the parental concern for mainly cultivating

behavioural-active aspects and civic values as well as their will to be part of the community`s

life. Comparison of semantic links in text: 1. Analysis for the key concepts:

2.Analysis of relations between the most frequent concepts:

1. behavioural-active dimension,

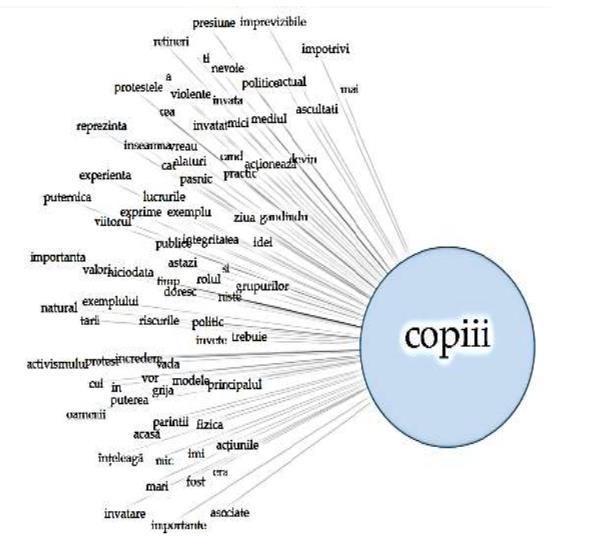

There are also two significant relationships between the codes children* and participate* (Figure

which highlight the intensity of the connection mediated by the words of the link, making a statement (two

concepts and the relations between them).

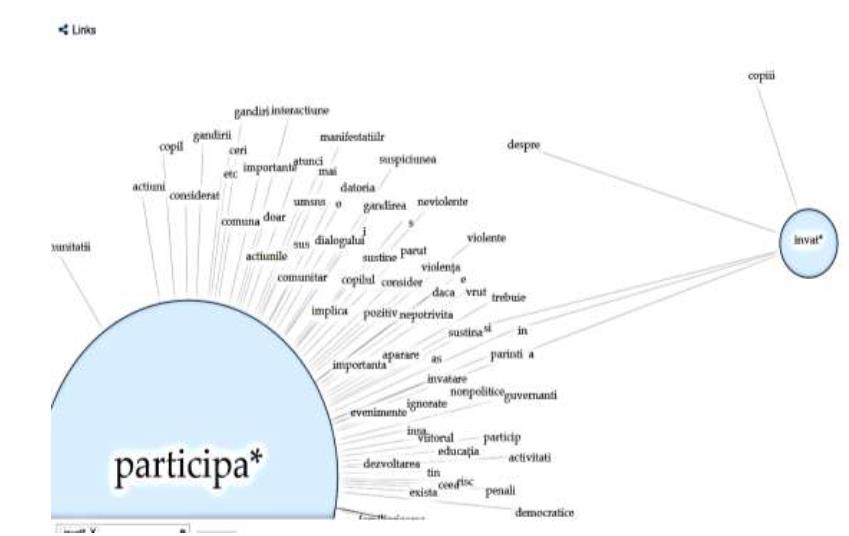

2.

structure of the two actors involved, the link between the children who learn and the parents who transmit

messages.

We also identify relational indicators belonging to the active-behavioural sphere, "involvement”, “expression”, “intervention”, “solving”, “protests”, “information”, “protect'' but also some of them related

to the evaluative sphere: ''good”, “values”, “community”, “the others”, “power”, “secure”, “independent”,

“political, “free". In other words, the content of learning mainly refers to behaviours, but also to appreciative

and evaluative aspects. This relationship reveals that learning refers both to active and behavioural practice

regarding the good example of parents and significant adults around.

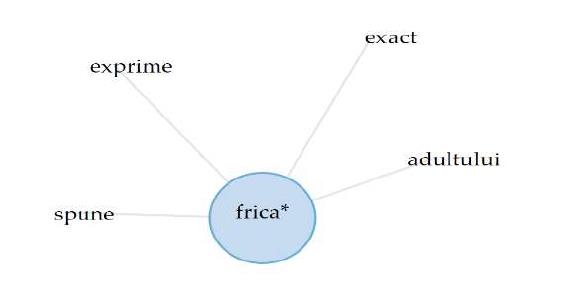

1.

fearful of saying”, “not being afraid to express yourself”.

The concept maps are tools for organizing and representing the information in the text unit. The

concept map, as a graphical representation of the relations between concepts, aims to indicate the direction

of the relationship between them, trying to create a model of the general meaning of the concept of value,

which can offer the possibility to analyse them through comparison. There are two significant relationships

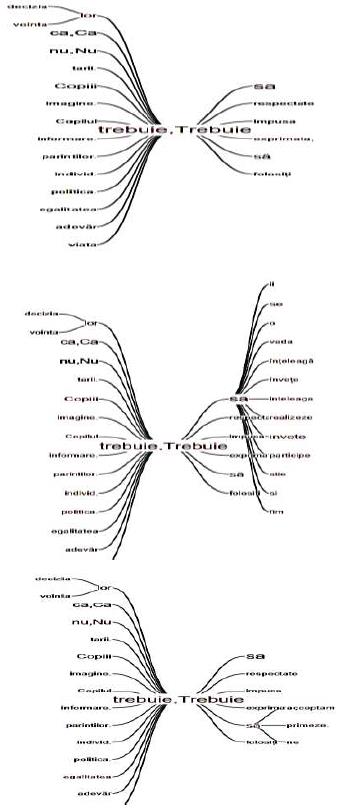

involving the codes protest* and must*, which highlights the intensity of the relationship mediated by the

link words, making a statement.

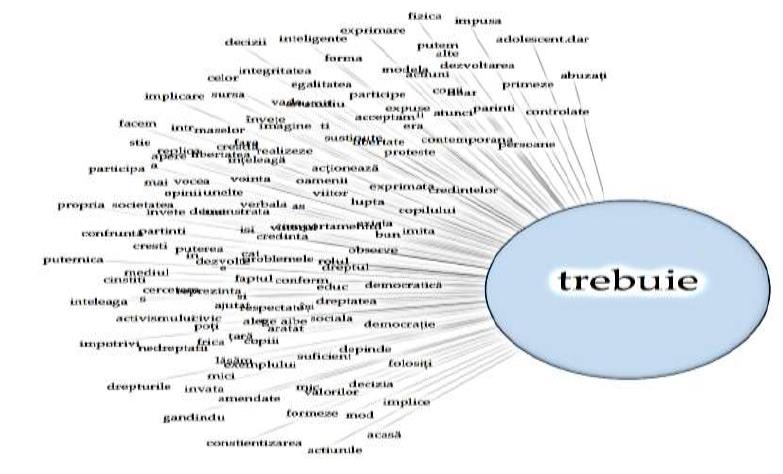

The word "must" has been identified in the context of analysis as having the highest frequency

among all the indicators, which has led us to deepen the analysis of its link with other concepts. Thus, by

realizing the map-concept (Figure

connection with decision and will (volitional and active dimension), but also with elements belonging to the cognitive sphere such as “to learn”, “to understand”, “to see”, as well as with verbs like “to accomplish”,

“to participate”, “to accept”, “to prevail”.

Conclusion

Considering concepts in the form of "ideative nuclei" (Agabrian, 2006, p.99), identified in the

respondents' answers to the three open questions in the online survey, we will consider that the ideological

nuclei of the messages that parents want to convey to their children have a pronounced behavioural-action

and an attitudinal predominance. Adults want to convince their children that there is a need (imperative

"must") for involvement and participation, by following their example, with reference to the evaluative

dimension. Another key concept that is related to the first one is the indicator civic* which defines the

attitude of the public protests and manifestations, although it is more recognized at the implicit level in the

answers received and less explicitly in the written messages and in the messages displayed in public space

on banners. Regarding the evaluative dimension, frequent reports are verbal testimonies such as "not to steal", "not to lie’’, placed in contrast to what is desirable. For children the message sent is the will to avoid

doing what is not in accordance with the generally accepted civic and moral values.

Although there were found in the parents' answers to the questionnaire, both references to cognitive and

affective dimensions are at a secondary level related to the attitudinal and behavioural - active elements

promoted. The emotional aspects invoked are “

mentioned in the analysis unit 3 times. What has been specifically and somewhat atypically has been the

invocation of fear, denial, "not to be afraid," that refers to history, functioning as an intention to demolish,

to defeat some fears of the past.

References

- Agabrian, M. (2006). Analiza de conținut. [Content analysis] Iași, Editura Polirom.

- Allen, J. (1989). Research in Review: children’s political knowledge and attitudes. Young Children, 44, pp. 57-61.

- Almond, G.&Verba, S. (1963). Civic Culture. Political Attitudes and Democracy in Five Nations. Princeton: Legacy Library.

- Almond, G.& Powell, Jr. G. (1966). Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

- Bragaw D. (1989.) In Training to be a Citizen: the elementary student and the public interest, Social Science Record, 26, pp. 27-29.

- Dogan, M.& Pelassy D. (1993). Cum să comparăm națiunile, [How to compare nations]. București: Ed. Alternative.

- Easton, D.& Dennis, J. (1969). Children in the Political System. Origins of Political Legitimacy. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Greenberg, E. (2009). Political Socialization. New York: Lieber-Atherton.

- Greenstein, Fred I. (1968). „Political Socialization”. In Sills D., Merton R., International Encyclopedia of Social Sciences, vol. 14, New York, Macmillan Publishers Company.

- Kawata, J. (1986). The Child’s Discovery and Development of ‘Political World’: a note on the United

- States, Konan Law Review, 21, pp. 233-265.

- Opp, K.-D. (2009). Theories of Political Protest and Social Movements:A Multidisciplinary Introduction,

- Critique, and Synthesis.New York, Londra: Routledge.

- Shaheen, J. (1989). Participatory Citizenship in the Elementary Grades. Social Education,53, pp.361-363. Ross, A. (1984). Developing Political Concepts and Skills in the Primary School. Educational Review, 36, pp. 131-139.

- Turner, R.H. (1969). The Public Perception of Protest. American Sociological Review, 34(6).

- Voicu, B. (2010). Valorile și sociologia valorilor. [Values and sociology of values] in Vlăsceanu L.(coord.),

- Sociologie, [Sociology] Iași, Polirom.

- Stiri.ONG. (2017). Copiii și democrația. Ce cred părinții activi social? Chestionar. [Children and

- democracy. What do socially active parents think? Questionnaire] Retrieved from

- https://www.stiri.ong/ong/civic-si-campanii/copiii-si-democratia-ce-cred-parintii-activi-social

- chestionar.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-066-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

67

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2235

Subjects

Educational strategies,teacher education, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Popa*, L. (2019). Children, Media And Democracy. Romanian Children Participating In Protests. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 67. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1543-1554). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.03.189