Abstract

It is a well-known fact that motivation represents a fundamental role in the general equation of the whole teaching-learning process, so that each teacher should know on one hand elements that reveal the specificity of the motivation activity, and on the other hand to master the levers or the ways to amplify it in the complex learning process. After a brief incursion into the vast and complex field of the significances of the concept of motivation, highlighted by psychological literature, we move to the typology of the reasons that support the learning activity. Knowing the types of reasons involved in learning, ways to increase motivation can be identified, accessible to teachers, but also to students. Qualitative research has been carried out for the purpose of observing the extent to which teachers in pre-university education have a functional grid to analyze and appreciate students' motivational status for learning, and have a set of effective levers to enhance and supports motivation and ability to use these resources in a differentiated way. The information was collected by applying a survey questionnaire. The results of the study show that in school practice, although the problem of decreasing motivation for learning is quite common, neither teachers nor students have always and to a satisfactory extent practical, applicable and effective strategies to solve it.

Keywords: Motivationmotivation typesimprovement strategiesmotivation factorsmotivation indicators

Introduction

In the category of internal learning conditions, motivation always occupies an essential place. That is why the teacher's great challenge with the students was, is and will be to identify the specific factors that motivate each student and the levers through which these factors can be maintained and amplified. In this difficult approach, there is a need for good collaboration between the teacher, the student and the family, the harmonization of their educational influences for the benefit and good of the children.

Problem Statement

Definitions of motivation

In the case of motivation, there is no conceptual ambiguity as it happens with other psychological processes and activities, and this is a positive aspect both for the evolution of the science of psychology and for the daily educational practices. Space constraints impose a limitation on the incursion into the literature that addresses the issue of school motivation. Thus, in the Great Dictionary of Psychology (Ardeleanu, Dorneanu, & Baltă, (2006) motivation is defined as "physiological and psychological processes responsible for triggering, maintaining and cessation of behavior, as well as the appetitive or aversive value given to the environmental elements on which it is exercised that behavior "( p. 773). In another paper of this kind, the authors prefer a more conceptual description of the motivation: "motivation is part of the relationship of behavior; thanks to it, the needs turns into goals, plans and projects; the subject actively seeks forms of interaction in such a way that certain relationships with certain objects are necessary or indispensable to functioning" (Doron & Parot, 2006, p. 513). In the above-mentioned approach, the development of motivation involves: channeling needs (learning); cognitive development (goals and projects); instrumental motivation (means and objectives); personalization (functional autonomy).

Turning now to other types of sources, Hayes and Orrell (1997) state that "the study of motivation is about exploring the underlying issues of our actions: how do we get to act and what kind of factors influence our actions” (p. 237) and Atkinson et al., (2002) define the motivation as "the study of wishes and needs relating to the factors that energize and direct behavior" (p. 441) Also, Reuchlin (1999), referring to the motivation, states that "it is particularly important to examine the factors that trigger the subject's activity, which guides it towards certain purposes that allow it to be extended if the goals are not immediately reached, or that stop at some point" (p. 391).

In the perimeter of Romanian psychology, Golu (2002) defines the motivation as "a specific form of reflection that signals to the command-control mechanisms of the personality system an oscillation from the initial equilibrium state, an energetic and informational deficit or a need to be satisfied” (p. 472). "An important definition also provides Zlate (2006) who considers that "motivation is an important lever in the process of self-regulation of the individual, a driving force of his entire psychic and human development” (p. 244). This means that selection and assimilation, as well as sedimentation of external influences, will depend on the motivational structures of the person. "A final definition of motivation, which we highlight, belongs to Popescu-Neveanu (2013) which reveals the specificity of the motivation in the following manner: "motivation fulfills a dual function in the person's system: a) having a reflective nature, the manifestation of causality in human behavior, motivation connects the person of the world and maintains it in the sphere of external determinism, which is vital for the person's being; b) being causally reproduced, transformed, and sedentary in time within the person, motivation operates a certain interruption in the chain of causes from the outside, gradually taking over it as the dominant command point in the person's behaviour (p. 705).

Typology of Reasons Involved in Learning Activities

Being a multi-purpose and extremely complex activity, motivation also shows a typology of quite varied motives, which in general remains relatively constant for most authors. We limit ourselves to summarizing only two which, of course, we present them in order the chronology of occurrence. Thus, Neacșu (1978), which dissociates the following types of motives: professional motives (explains the determination of the student to learn by his desire to prepare for the practice of a particular profession); socio-moral reasons (derived from the student's desire to be useful, to get the appreciation of others - teachers, colleagues or parents); individual reasons (refers to the need to affirm the student, the act of learning being made for "becoming someone"); relational motives (occurring on the background of relationships with other direct or indirect participants in the educational process); affective motives (such as fear of parents, shame of teachers, fear of the repercussions of getting a small grade); reasons for self-realization (are related to students' aspirations for personal fulfillment); stimulatory motives (materialized in praise, appreciation, encouragement); inhibitory motives (materialized in punishment, in conflict situations); motives grouped around a wish for success; reasons that are emphasized in the presence of some special skills in the instructive-educational process. All these reasons are perceived in everyday didactic activity according to the characteristics of the classroom but also according to the individual peculiarities of the pupils.

Also regarding the types of reasons, Pănișoară (2017) refers to Abraham Maslow's famous approach that identified several types of needs: physiological needs; security needs; membership requirements; needs of esteem; self-fulfillment needs. The conclusion of this typology is not to try to honor the needs of the last steps unless you previously satisfy those on the lower steps.

Ways to Boost Motivation for Learning Activity

Since the motivation is determined by a complex of variables, both inside and outside the subject, the teachers need to know what kind of motivation each student possesses in order to find the means and the ways to motivate him/her better for the activity learning. Identifying each type of motivation can be facilitated by knowing some indicators that are specific to one type or another. For example, in the case of intrinsic motivation, Barth (2002) considers that the main indicators are the following: a high level of concentration; the existence of spontaneous initiatives; the existence of an energetic attitude; the existence of a climate of free exchange and obedience to the other; expressing a shared pleasure; an expression of confidence. Based on the identification of the motivational structure of the pupils they work with, the teacher can design a specific strategy to amplify their motivation for the learning activity. The resources available to the teacher in this process are both the specialty literature and, above all, the didactic creativity, which is practically unlimited.

In relation to strategies that can amplify students' motivation for learning, we will selectively present some points of view by specialists. Thus, Osterrieth (1978) considers that among the possible ways of enhancing the motivation of the most important students are the following: permanent information of the pupils about the performances obtained at different types of activities; ensuring success in learning; the use of praise and not blame. Another author worthy of mention, Beauté (1994) lists other ways of enhancing motivation such as emphasizing the importance of content in different contexts of use, and also making students aware of the fact that learning inevitably implies and the consensus on the special efforts they have to make.

On the same note, Biehler and Snowman (1986) offer a series of suggestions for teachers, of which we selectively present the most important ones: making sustained efforts from teachers to make each subject interesting; using behavioral modification techniques to help students work for distant purposes; taking into account the individual differences between pupils in terms of their abilities, attitude towards school, individual work rhythm etc.; meeting the needs of the pupils (psychological, safety, affiliation, respect, etc.); increasing the number of attractive activities and diminishing the danger of non-involvement of students; providing (or creating) direct learning experiences that provide a realistic level of aspirations, enhancing self-confidence etc.; encouraging students who have problems, who have difficulties in overcoming them and developing self-confidence; the requirement for students to translate what they have learned into different educational disciplines into practice.

Very interesting and very effective are the proposals of other authors when it comes to enhancing students' motivation for instruction and learning. For example, Viau (1999) emphasizes the role of determining factors (conditions) for school motivation as levers of action to trigger and amplify it: the perception of the value of an activity; the perception of one's own ability to carry out an activity; the perception of the controllability (level of control over an activity). Regarding the perception of the value of an activity, it should be noted that the higher the value of an activity, the greater the degree of motivation of the students will be amplified. On the other hand, the more an activity will be perceived as less valuable, the less motivated and less interested in participating in its realization. As regards the student's perception of his/her competence to perform an activity, it can be stated that the pupil will become more motivated for an activity when he/she realizes that he/she possesses the necessary skills to accomplish that activity and less motivated in the opposite situation . Consequently, students need to be helped to develop skills to carry out the various school activities and to match their competencies to the various categories of tasks they will have to solve in the different moments of the training. They also need to be helped by the teacher to improve their perceptions of their competencies. In this sense, some authors (Marzano et al., 1992, cited in Viau, 1999, p. 176) offer teacher suggestions to help students improve perceptions about their own skills: students to set their own standards of success in a realistic manner and not to constantly appreciate through their colleagues; students should not be judged too severely when committing mistakes and understand the role and importance of error in the learning process (to distinguish between error and guilt/fault); in the work with mediocre students, the teacher divides activities into microactivity; when the context is favorable, the teacher allows each learner to define his/her own learning goals (goals must be clear and short-term), depending on their own capacities (the teacher must ensure that students know and want to use learning and self-regulatory strategies); students are aware of what they are doing well and what needs to be improved. Finally, with regard to the perception of the controllability of an activity, controllability means that the student anticipates, on the one hand, the way in which an activity will take place (its moments and sequences) and on the other hand the consequences or what follows of its deployment.

Viau (1999) offers a series of suggestions to improve students' perceptions of the level of control they can have on how learning is done: a) empowering pupils with the learning process in which they are involved, which assumes organizing, planning and managing learning. The teacher has to teach them how they can control their own learning and create the conditions to do it; b) organizing training and learning activities to enable students to make choices and take up learning; c) planning activities with a level of difficulty and complexity corresponding to the students' real abilities and possibilities, which are desirable factors in the causal attribution of the achievements (successes or failures) obtained in learning; d) instrumenting students with learning and self-regulatory strategies and their awareness of their importance in learning; e) raising students' awareness of the importance of attribution perceptions on motivation for learning and, implicitly, on school results/performance; f) avoid embarrassing or debilitating situations that can determine/affect the affective-emotional state of the students; g) emphasize the importance of the effort and time investment in learning, which are essential factors for success.

At all this, teachers can add others depending on context and specific didactic creativity

Research Questions

Qualitative research has been conducted for the purpose of finding and addressing the causes that maintain and amplify a state of discontent among teachers about the level of motivation of students to learn. Thus, the questions that arise from the results of the existing researches are natural:

These are just a few questions the answer of which could explain the situation in schools.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the research is to establish the extent to which the teachers in the pre-university education have a

The assumption from which we start is that not all teachers use a concrete, applicable and effective strategy, scientifically grounded, to ensure an appropriate level of student motivation for learning

Research Methods

The research was carried out on a group of 50 teachers in the pre-university education (80% women and 20% men), participating in the training courses in order to obtain the didactic degree II.

The questionnaire we used contains 8 open questions, leaving the respondent the opportunity to propose more answers. The percentages calculated relate to the number of respondents (50) and record the frequency of the response. (Table

Findings

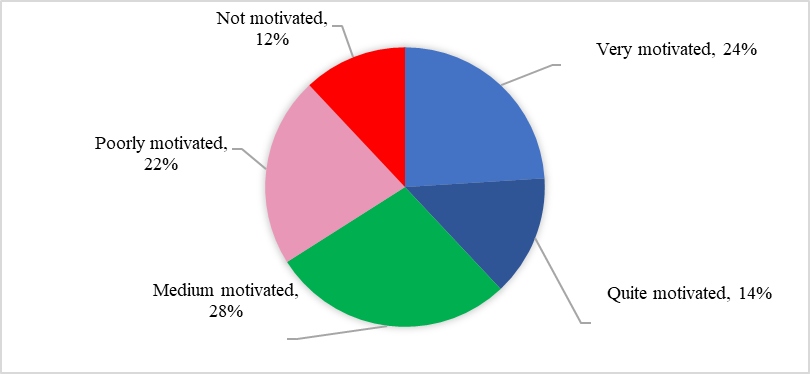

The first question highlights the level of motivation of the students in the perception of the teaching staff involved in the study: Q1.

The next two questions address the strategies used by teachers to assess students' motivation. The first question concerns the level of motivation indicators: Q2.

The table

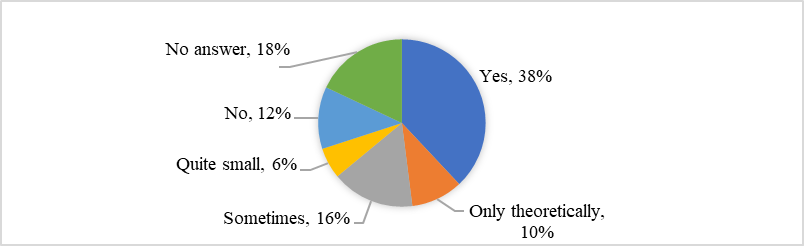

By the second question I have been looking at the teacher's work tool for assessing the level of motivation of students: Q 3.

As can be seen, most answers show that teachers either do not understand the question (32%) or do not answer (30%), which means that they do not have a didactic tool (a grid) for assessing the motivational status of pupils.

Regarding

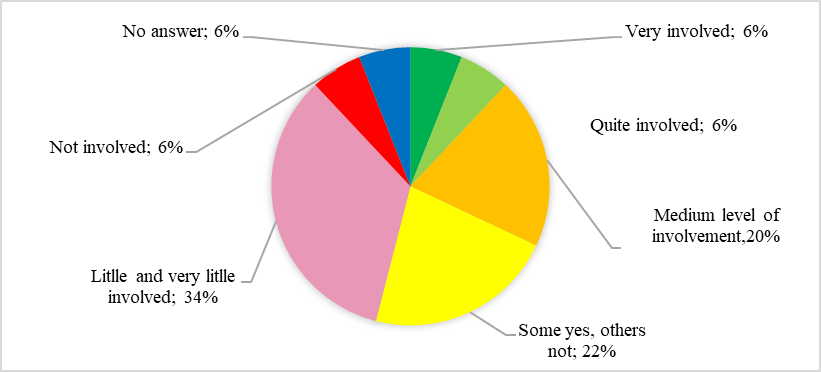

The following question relates to teachers' opinion on the degree of parent involvement in motivating their children to learn: Q5.

It can be noticed that teachers generally perceive a poor involvement of parents in motivating students to learn: 40% of the answers show that parents are little, very little or not involved in motivating pupils, and 42% of them show a relatively medium level involvement (environment involved, some yes, others not). And to this question, 6% of the teachers in the research group do not have an opinion in this respect, which can be interpreted as a lack of interest in it.

With regard to

To Q7:

The last question in the questionnaire pertains to the teacher's perception of the level of compatibility between student, family and teacher views on school motivation: Q 8.

Conclusion

Although the importance of motivational factors for learning success in schools is unanimously acknowledged, the conditions necessary to ensure an optimal motivational level of learning are not always met in school practice. Thus, not all teachers use a didactic tool/grid to assess students' motivational status with well-defined and individualized indicators that characterize the motivational structure of each pupil and scales of measure of motivation. Also, not all teachers have a set of effective action levers to amplify and support pupils' motivation for learning, resources built on a good understanding of the motivational structure of each student and used in a differentiated way. For this, more family support and better and more effective communication between the teacher, the family and the student is needed, which is not always the case.

In conclusion, although the problem of lower motivation for learning is quite common, neither teachers nor students or parents always and to a satisfactory extent have concrete, consistent, applicable, and effective solutions to solving it.

References

- Ardeleanu, A., Dorneanu, S. & Baltă, N. (2006). Marele dicționar al psihologiei (trans.) [The Great Dictionary of Psychology]. București: Trei.

- Atkinson, R.L., Atkinson, R.C., Smith, E.E. & Bem, D.J. (2002). Introducere în psihologie (trans.), [Introduction to psychology]. București, Tehnică.

- Barth, M. B. (2002). Le savoir en construction. Paris: Ed. Retz.

- Beauté, J. (1994). Les courants de la pédagogie contemporaine. Lyon: Chronique Sociale.

- Biehler, R & Snowman, J. (1986). Psychology Applied to Teaching. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Doron, R., Parot, Fr. (Eds.) (2006). Dicționar de psihologie (trans.) [Dictionary of psychology]. București: Humanitas.

- Golu, M. (2002). Fundamentele psihologiei (Vol. I, II) [Fundamentals of Psychology]. București: Fundației ”România de mâine”.

- Hayes, N. & Orrell, S. (1997). Introducere în psihologie (trad.) [Introduction to psychology]. București: All Educational.

- Neacșu, I. (1978). Motivație și învățare. Studiu asupra motivelor învățării școlare în ciclul gimnazial. [Motivation and learning. Study on the reasons for school learning in the gymnasium cycle]. București: E.D.P.

- Osterrieth, P.A. (1978). Faire des adultes (14th ed.). Bruxelles: P. Mardaga.

- Pănișoară, I.-O. (2017). Ghidul profesorului [Teacher's Guide]. Iași: Polirom.

- Popescu-Neveanu, P. (2013). Tratat de psihologie general [Treated general psychology]. București: Trei.

- Reuchlin, M. (1999). Psihologie generală. (trans.) [General psychology]. București: Științifică.

- Viau, R.. (1999). La motivation en contexte scolaire (2nd ed.). De Boeck Université.

- Zlate, M.(2006). Fundamentele psihologiei [General psychology]. București: Universitară.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

15 August 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-066-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

67

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2235

Subjects

Educational strategies,teacher education, educational policy, organization of education, management of education, teacher training

Cite this article as:

Căprioară*, D., & Frunză, V. (2019). Effective Strategies To Improve Student Motivation For School Learning. In E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues, vol 67. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1488-1497). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.08.03.183