Abstract

A reflection on urban experience and space leads to a greater complexity of study methods and requires analyzing not only at culturological and sociological but also at socio-psychological levels. The social fabric of the city and its substance are expressed by images the city inspires in its residents. The city estimates are often based on subjective opinions of people, and they are, by their nature, heterogeneous, fragmentary and non-uniform. There are great differences in people’s perceptions depending on their status, age, gender, faith as well as psychological wellbeing, level of trust/mistrust, etc. The city does not exist apart from its residents’ perception. They perceive external events and conditions, assess them and then shape their representations of the city. In the given study Yekaterinburg was analyzed in the context of its residents’ reactions: how the citizens evaluate and perceive the place of their residence in terms of its being secure, comfortable, friendly, and so on. The data obtained in the course of the survey were later translated into a psychological atlas of the city which is a peculiar “mirror” reflecting the city residents’ perceptions of how they find themselves within the space of the cosmopolitan centre. The survey revealed that insecure or unordered environment can fuel a sense of helplessness and fear that life is chaotic and pregnant with uncontrollable threats. It was also shown that the quality of life of the citizen depends not only on socio-economic development of the region but also on socio-psychological wellbeing of the city residents.

Keywords: Psychology of the cityYekaterinburgpsychological atlassocial representationspsychological security

Introduction

Life quality and people’s wellbeing has long been the focus of theoretical and empirical research. The majority of modern city studies include objective approaches to examining life quality and wellbeing levels of urban residents. As a result, coefficients relating to social and physical environment are created. These coefficients are easy to measure, estimate, and model (for example, salary, environment, environmental pollution, etc.) (Fakhruddin, 1991; Knox, 1974; Niewiaroski, 1965). However, in the last decade a greater attention has been given to subjective wellbeing’ aspects based on the data of sociological, psychological and socio-psychological research on people’s assessment of individual health, wellbeing, life satisfaction and happiness (Downs & Stea, 1973; Downs, 1977; Fischer, 1992).

The “city” subject is interdisciplinary and is disclosed through various research aspects: from mental maps of cities to city “mobilities” visualization. Insight into urban experience and space leads to sophistication of study methods and requires analysis not only at culturological and sociological but also at socio-psychological level. “It is interesting to note that there appears a category of an interpreted city space. This gives the opportunity to argue that a city’s meaning is embodied in its images thus regulating social interaction under distortion of social and communication structure” (Zinchenko & Perelygina, 2013, p. 105). Theoretical debates on possible links between subjective wellbeing and geographical, or much wider “contextual” conditions and characteristics (for instance, climate and socio-economic environment) (Ballas & Dorling, 2013) are being conducted. The significance of these characteristics and conditions in cities whose large population implies a greater range of individual differences is also investigated.

Jodelet (1982) suggests considering urban space as a “social and historic reality” where urban life experience of active subjects is concentrated. We no longer talk here about isolated individuals who react only to external irritants or internal processes functioning in the space of social meaning. Thus, Jodelet follows the transactional perspective of ecological psychology where man-environment-society are mediated, and man actively creates his own environment including historic, social and cultural background (as cited in Altman & Rogoff, 1987).

Taking into account the fact that greater parts of the world population live in big cities it is not surprising that a fast growing number of studies are focused on measurement of urban life quality and objective and subjective approaches (Arruda, 2010; Bomfim, 2010; De Alba, 2012; Glaveanu & Jovchelovitch, 2010; Haas & Levasseur, 2010; Jodelet, 2010; Priego & Jovchelovitch, 2010; Ramadier, 2010). It is worth noting that the city does not exist separately from its residents’ perception, and they perceive external events and conditions, assess them and then shape their perceptions of the city. In Zinchenko and Zotova’s (2013) opinion, “security/insecurity of the surrounding reality facilitates the formation of everyone's own sets of opinions, views and settings” (p. 111). Man has the dual world which involves both a world of immediately reflected objects and a world of images where an objective world is given to man (Leont’ev, 1979). The social structure of the city and its content are expressed by images the city has evoked in its residents. The city estimates are often based on subjective opinions of people who are, by their nature, heterogeneous, fragmentary and non-uniform. There are great differences in people’s perceptions depending on their status, age, gender, faith as well as psychological wellbeing, level of trust/mistrust, etc. As a result, there arises a problem of describing this specific area of psychological reality – a city world picture where man lives, a picture woven of his individual consciousness’ separate patches.

Problem Statement

Instead of the objective paradigm which has been practiced so far by domestic and foreign researchers for exploring city space and the city and which is based on the use of statistical indicators this study takes up the challenge of working out approaches and methods from the perspective of a subjective approach. The thing is that objective characteristics of the intensity of psychological phenomena often contradict subjective factors: the respondents’ attitude to life, level of trust and subjective wellbeing.

Research Questions

1. To identify the role of residential security for different categories of the population.

2. To reveal specific features of perceptions about Yekaterinburg in the representations of its residents.

3. To examine the city residents’ perceptions of different districts of Yekaterinburg.

4. To design a city map based on the dichotomy “secure/insecure”.

5. To single out the criteria which impact positive and negative perceptions of the environment.

Purpose of the Study

The study is aimed at designing a psychological atlas of Yekaterinburg on the basis of reconstructing “the city vision” through its dweller’s eyes.

Research Methods

1. Semantic differential with scales oriented to denotative attributes of the city such as: happy-unhappy, dynamic-static, friendly-cruel, secure-insecure, etc.

2. The method of mental maps as a way of visual reflection of the city residents’ perceptions about the city space and its objects.

3. The method of social mapping. Some particular locations of the city were linked to geographical references and placed on the city map by the respondents.

The data-processing methods included correlation analysis, distribution-free Mann–Whitney U-test, one-way ANOVA test. The data were analyzed via SPSS 20.0.

The sampling: 500 residents of Yekaterinburg aged from 18 to 65 belonging to different social groups. The respondents have been living and working for a long time and places of their residence and work are scattered throughout the city.

Findings

The study conducted identified that on choosing a location to live residents, in the first place, are guided by objective-subjective factors – housing affordability (per square meter price, this factor is the most significant for the majority of the testees), neighboring kindergartens, schools and factors of urban environment security (security of communications, safety of buildings, absence of industrial facilities with harmful, explosion-prone and fire hazardous components of production, security and safety of the district on a whole).

Priorities for young people are housing affordability, well-developed infrastructure and good-neighbor relations, and for residents above 35 it is more important to make an emphasis on psychological security of the environment and take into account the impact of these factors on their decision when choosing the place to live in megapolis. They also deny devotion to their “childhood playground” (I live here and everybody knows me), necessity to have good neighbors.

For childless people factors of urban environment security are practically insufficient and are placed closer to the end of the rating scale, they are more concerned with well-developed infrastructure, devotion to their “childhood playground” and good-neighbor relations whereas families with children focus on dwelling in a newly-built affordable house located in a prestigious, eco-friendly and secure district with kindergartens, schools and place of work at hand. It is typical of them to pay attention to factors of urban environment security and the impact of these factors on their choice of residence.

Thus, one of the key factors that effects the choice of Yekaterinburg citizens’ residence is psychological security of urban environment.

A significant empirical result was obtained in the course of the city assessment with the help of semantic differential method. It was found that the respondents perceive the image of Yekaterinburg as (characteristics are given by factor loading from greatest to least): “self-confident” (0.831), “strong” (0.814), “friendly”, comfortable”, “well-off” (0.811 all), “live”(0.809), “happy” (0.799), “optimistic” (0.797), “protected” (0.774), “dynamic”(0.766), “active”(0.755), “peaceful” (0.741), “understanding” (0.739), “moral” (0.712), “independent” (0.692) and “friendly”(0.660). It can be assumed that characteristics represented in the respondents’ consciousness indicate basic features common with the youth, i.e. in the eyes of Yekaterinburg citizens it is a “young and mobile city”, to a greater extent.

In the course of the survey the respondents were asked to name five places in Yekaterinburg which are “Most liked”, “Most disliked”, “Most famous”, etc., and the results obtained are as follows:

– The most favorite places: 75% respondents marked Central park for Recreation and Leisure, Historic Public Gardens/Dam (Plotinka), Olympic Embankment, Public botanical garden, October square, the Morosov’ Park; 50% respondents indicated Business centre “Vysotsky”, pedestrian street Vaynera, Opera and Ballet Theatre, 1905 year square, the lake Shartash, the Uktuss Mountains; every forth respondent singled out Yeltsin Centre, Ascension Hill, Literary Quarters, Cathedral-on-Blood, Federal University Walk, “Koltsovo” airport;

– Most disliked: 95% respondents named Uralmash/Kosmonavtov Avenue, Elmash, Old Sortirovka (Railway Sorting Station) area/Pekhotintsev Street), Chelyuskintsev Street, Vtorchermet (Secondary Ferrous Metals) neighborhood, Tagansky strip mall, Khimmash, Bus station, “roundabout at Kalina plant”;

– Most famous beginning with most popular: Historic Public Gardens/Dam (Plotinka), Cathedral-on-Blood, Opera and Ballet Theatre, Central park for Recreation and Leisure, Business centre “Vysotsky”, Ural Federal University area, Vaynera pedestrian street, Yekaterinburg City/October square, Yeltsin Centre, TV Tower, Tatischev and de Genin monument, Uralmash plant, Khimmash plant.

Therefore, in the respondents’ consciousness, “most liked” places are closely connected with “most famous” places, and almost all respondents relate city outskirts, little-known districts and roads with heavy traffic to “most disliked” places.

In the respondents’ consciousness, the city is divided into the following zones:

– “City of the rich” – “Tikhvin”, Krasnoarmeyskaya Street, territory with Radischeva–Vaynera–Lenina–Sakko and Vantsetti Streets, Krasny Lane, Karas’eozersky gated community.

– “City of the poor” – suburbs of every city district, Uralmash, Vtorchermet, Elizavet, Khimmash, Sortirovka, Elmash.

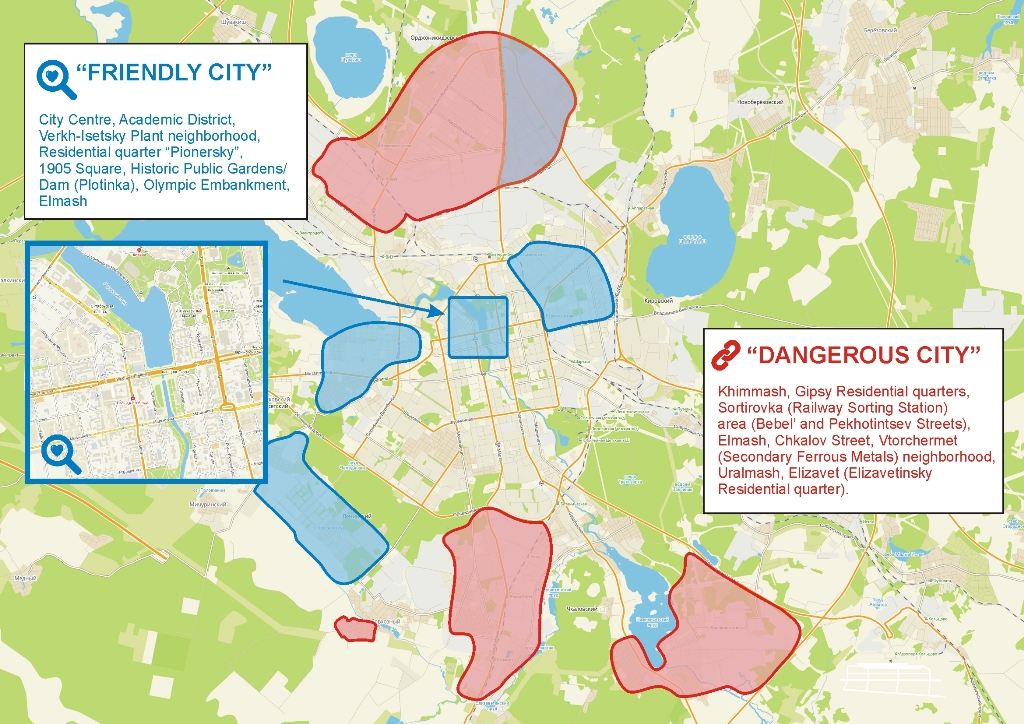

– “Dangerous City” – Khimmash, Gipsy Residential quarters, Sortirovka (Railway Sorting Station) area (Bebel’ and Pekhotintsev Streets), Elmash, Chkalov Street, Vtorchermet (Secondary Ferrous Metals) neighborhood, Uralmash, Elizavet (Elizavetinsky Residential quarter) (see figure

– “The city I like most” – Central park for Recreation and Leisure, Historic Public Gardens/Dam (Plotinka), Olympic Embankment, October Square, Public botanical garden.

– “The city I wouldn’t agree to live in” – Uralmash, Vtorchermet, Elizavet, Khimmash, Sortirovka, Elmash, the 7th Keys, Uktus, Concrete Goods plant area, Blue Stones residential area, city outskirts (old houses), quarters near industrial facilities.

– “The city I know best of all” – Downtown, Khimmash, South-West residential area, Uralmash, micro residential area “Botanical”, Bus Station area, Rubber goods plant neighborhood, “Academichesky” quarters, Elmash, Vaynera Street, Verkh-Iset plant (VIP) embankment, Federal University residential area.

– “The city I know the least” – Uralmash, Elmash, city outskirts.

– “The city of snobs” – the “Hyatt” hotel, The Ural Federal University after the 1st Russian President B. Yeltsin, Downtown, “Tikhvin” quarters, territory with Radischeva–Vaynera–Lenina–Sakko and Vantsetti Streets, blocks of houses in Sverdlova–Chelyuskintsev–Krasny Streets (“Dinamo” stadium area), House of Printing – Lenina and Turgeneva Streets, Yeltsin Street, Marshal Zhukov street.

– “The city of ethnoses” – “Tagansky strip mall”, Sortirovka, Gipsy Residential quarters, Chkalova Street, “Zavokzalny” (beyond the Railway station neighborhood), Ctarykh Bolshevikov Street, Vtorchermet.

– “The city I would move to if possible” – Karas’eozersky gated community, Krasny Lanes (“Dinamo” stadium area), right-bank VIP quarters, Serova, Surikova, Radischeva Streets, “Academichesky” quarters, Krasnoles’e neighborhood, micro residential area “Botanical”.

– “The friendly city” – Downtown, “Academichesky” quarters, VIP quarters, “Pioneers settlement”, 1905-year Square, Historic Public Gardens/Dam (Plotinka), Olympic Embankment, Elmash (see figure

– “The city of non-mainstreams” – “Uralsky Rabochiy” Printing house area, Drama theater area, October Square, Vaynera Street (backyards), Ural Federal University area, location near Central Department store “Passazh”.

– “The city of excursionists” – Historic Public Gardens/Dam (Plotinka), Vaynera pedestrian street, Literary Quarter, Cathedral-on-Blood.

– “The city of students” – Student town – territory near Ural Federal University, Mira–Malysheva Streets, adjacent territory of all Yekaterinburg higher schools.

– “Trading City” – shopping and leisure centers “Grinvich”, “Mega”, “Alatyr”, “Tagansky strip mall” and “Dirizhabl’, Vaynera pedestrian street.

– “The city of socio-economic activity” – Business centers “Antey” and “Vysotsky”, Fevralskoy Revolutsii and Yeltsina Streets, City Administration, Yekaterinburg-City.

– “The city of pleasures” – shopping and leisure centers “Grinvich”, “Alatyr”, “Raduga-Park”, Central Department store “Passazh”, Central park for Recreation and Leisure, the Uktus Mountains.

Conclusion

Changes in the Russian cities’ landscapes should be read through the lens of the citizen, his perception of place, everyday activities, and actualization of public places. Like any other complex systems the city cannot be assessed unequivocally, it is evident that such a system will produce a host of citizens’ subjective opinions and perceptions. The study’s analysis of Yekaterinburg was based on the city residents’ characteristics through evaluating such factors as: personal wellbeing and emotional comfort, satisfaction of an individual’s need for security, the city level of security/insecurity, efforts made by city authorities to provide security. In other words, a citizen’s life quality depends not only on socio-economic development of the region but also on socio-psychological wellbeing of its residents. In the estimation of the respondents Yekaterinburg as the city of “the First Russia” (Zubarevich, 2015) possesses the status attractive for its residents, according to their perceptions it is “dynamic”, “young”, optimistic” and “friendly”. On the other hand, some stereotypes with regard to “unfavorable districts” were established. Consequently, it is not necessary for a real threat to exist, unsavory reputation is enough to prevent a person from having a desire to live in this neighborhood, moreover, he will try to avoid appearing in a notorious place.

The study shows that the city value depends on the citizen’ emotional wellbeing, on how secure and comfortable his life in megapolis is. However, psychological security of urban environment rides on both the individual himself, perception of his living in the space and the city powers participation in provision megapolis security, residents’ wellbeing and emotional comfort protection.

The proposed approach for studying urban space can contribute to researchers’ dynamically organizing and visualizing several dimensions and is a potentially powerful and promising tool which can greatly facilitate socio-psychological research efforts.

The societal value of the city atlas resides in its use as an instrument to operationally monitor social wellbeing of the population. It reflects the dynamics of trends in the field of psychological security of personality and society and plays an important role in the formation of a feedback between society and the authorities for further development of society.

Acknowledgments

The article was supported with a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (project № 16-18-00032-П).

References

- Altman, I., & Rogoff, B. (1987). World views in psychology: trait, interactional, organismic and transactional perspectives. In D. Stokols & I. Altman (Eds.), Handbook of environmental psychology (pp 7-40). New York: Willey.

- Arruda, A. (2010). Brésil du nord au sud: les cartes mentales et les représentations socials. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Representations. Tunis: Les Editions Apolonia.

- Ballas, D., & Dorling, D. (2013). The geography of happiness. In S. David, I. Boniwell & A. Conley Ayers (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of happiness (pp. 465-481). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bomfim, Z. (2010). Cidade e afetividades. Estima e construçao dos mapas afetivos de Barcelona e de Sao Paulo. Fortaleza: Ediçoes UFC.

- De Alba, M. (2012). A Methodological Approach to the Study of Urban Memory: Narratives about Mexico City. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung / Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 13(2), Art. 27. Retrieved from http://nbn-resolving.de/urn:nbn:de:0114-fqs1202276

- Downs, R., & Stea, D. (Eds.). (1973). Image and Environment: Cognitif mapping and spatial behavior. Chicago: Aldin Publishers Co.

- Downs, R. M. (1977). Maps in Mind: Reflections on Cognitive Mappings. New York: Harper & Row.

- Fakhruddin, A. (1991). Quality of Urban Life. Jaipur: Rawat Publication.

- Fischer, G. (1992). Psychologie sociale de l´environnement. Toulouse: Privat.

- Glaveanu, V., & Jovchelovitch, S. (2010). Exploring the world of Rumanian Children: a study of children’s representations in a school and child-care centre context. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Representations. Tunis: Les Editions Apolonia.

- Haas, V., & Levasseur, E. (2010). Quand la ville nous parle: représentations sociales et mémoires collectives. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Representations. Tunis: Les Editions Apolonia.

- Jodelet, D. (1982). Les représentations socio-spatiales de la ville. In P. H. Derycke (Ed.), Conceptions de l’espace (pp. 145-177). Paris: Université de Paris X-Nanterre.

- Jodelet, D. (2010). La memoria de los lugares urbanos. Alteridad, 20(39), 81-89.

- Knox, P. L. (1974). Spatial Variations in Level of Living in England and Wales in 1961. Transactions, Institute of British Geographers, 62, 1-24.

- Leont’ev, A. N. (1979). Psychology of the image. Moscow State University Bulletin. Series 14. Psychology, 2, 3-13. [in Russian].

- Niewiaroski, D. H. (1965). The Level of Living of Nations: Meaning and Measurement. Estadistica. Journal of the Inter America Statistical Institute, 64, 3-31.

- Priego, J., & Jovchelovitch, S. (2010). Children draw the public sphere: a study of children’s representations of the public sphere in Mexico. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Representations. Tunis: Les Editions Apolonia.

- Ramadier, T. (2010). Proposition méthodologique pour comparer les représentations socials de l’espace urbain. In Proceedings of the 10th International Conference on Social Representations. Tunis: Les Editions Apolonia.

- Zinchenko, Y. P., & Perelygina, E. B. (2013). A Secure City: Social-psychological Aspects. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 86, 104-109.

- Zinchenko, Y. P., & Zotova, O. Y. (2013). Social-psychological Peculiarities of Attitude to Self-image with Individuals Striving for Danger. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 86, 110-115.

- Zubarevich, N. (2015). Four Russias and a New Political Reality Reality. In L. Aron (Eds.), Putin’s Russia. How It Rose, How It Is Maintained, and How It Might End (pp. 22-35). Washington: American Enterprise Institute.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 July 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-063-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

64

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-829

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Zotova*, O. Y. (2019). Psychological Atlas Of Yekaterinburg In Social Representations Of Its Citizens. In T. Martsinkovskaya, & V. R. Orestova (Eds.), Psychology of Subculture: Phenomenology and Contemporary Tendencies of Development, vol 64. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 816-823). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.07.106