Abstract

Ethnic identity is a critically significant factor for understanding psychological functioning and wellbeing and crucial for individuals’ self-esteem. In the context of psychological security the problem of ethnic identity transformation in cross-ethnic interaction has not been a focus of research so far. Psychological security as a state of personality when a person can satisfy his basic need for self-preservation and his own (psychological) perceived security in a socium can act as the most significant predictor of mature ethnic identity. And identity statuses can facilitate self-acceptance. The study was meant to explore specificity of relationships between a status of ethnic identity and personality psychological security. The analysis of ethnic diversity of the RF regions where the key criterion was the population’ belonging to various ethnic groups resulted in defining two regions of the study: the Sverdlovsk region as a territory with average ethnic diversity and the Republic of Bashkortostan as a highly diverse in terms of ethnic identity region. The quota sample of the Sverdlovsk region constituted 512 people and that of Bashkortostan – 508 persons. The study revealed that in the regions with moderate ethnic diversity the higher psychological security is, the higher the persons’ awareness of their ethnic roots: people want to learn more about their ethnic groups, its history, traditions and customs. And, conversely, negative attitudes to one’s ethnic belonging are associated with a lower level of psychological security. A search for identity, awareness of ethnicity positively correlates with personality psychological security irrespective of ethnic diversity of the milieu.

Keywords: Ethnic tolerancepsychological securityethnic identity

Introduction

Ethnic identity has been the subject of increased interest for several decades. It has come to be viewed as an important psychological source of emotional experience (Phinney & Ong, 2007). And, in spite of the fact that the number of studies has been growing, the results remain controversial (Koneru, Weisman de Mamani, Flynn, & Betancourt, 2007).

Many groups of ethnic minorities experience stress, ethnic identity crisis and psychological discomfort due to pressure imposed on them. According to Torres, Driscoll, and Voell (2012) findings chronic stress can cause physical and mental problems. In addition, some confusion about new ethnic identity plays a crucial role in the state of the person’s psychological security. Researchers have proven an impact of ethnic identity on human thoughts, views, emotional states and actions.

Today three approaches to ethnic identity studies could be distinguished:

Approach 1 – refers to the study into ethnic identity from Erikson perspective, who considers changes in the process of identity with time (as cited in Phinney, 1989). Erikson (1968) argues that external and internal factors influence human development. Personality depends of interactions with other people and its development can change in step with changes in the environment.

Approach 2 – focuses in the substance of ethnic identity at this moment in time (Sellers, Rowley, Chavous, Shelton, & Smith, 1997). Ethnic identity can be defined as “a factual ethnic behaviour that people practice together with attitudes to their ethnic groups” (Phinney, 1993, p. 64).

Approach 3 – a synergetic approach considering personality development together with immediate content of ethnic identity at every given moment (Phinney, 1992).

Proponents of this approach have concluded that ethnic identity is a progressive process which occurs with age. Thus, older teenagers have a stronger ethnic identity that younger ones (Phinney, 1989).

Phinney’s (1989) model of ethnic identity describes a person’s understanding of his/her ethnic belonging. The author identified four components of ethnic identity:

– self-identification,

– affirmation and belonging,

– ethnic behavior and practice,

– ethnic identity achievement.

The first component, self-identification, assumes attitudes towards one’s self. The second component, affirmation and belonging, refers to pride a person feels being a part of a group. The third component, behavior and practice, involves such social components of an ethnic group’ belonging as language, religion and cultural traditions. The final component, ethnic identity achievement, relates to a realistic assessment of one’s ethnic belonging, commitment to one’s ethnic group and acceptance of other ethnic groups (Phinney, 1992). Phinney has drawn a conclusion that the second and the fourth components are decisive for the development of ethnic identity.

Ethnic identity is a critically significant factor for understanding psychological functioning and wellbeing (Phinney & Kohatsu, 1997) and crucial for individuals’ self-esteem (Phinney, 1990). Psychologists view ethnic identity as a personality resource (Thoits, 1995) that act as a cushion in face of stress (Al-Issa, 1997). Ethnic identity mitigates the impact of discrimination on mental health and additionally determines the effectiveness of various difficulties’ overcoming.

In relation to research on the development of ethnic identity studies into psychological security in its interrelations with identity statuses are of academic interest. Recognizing the significance and role of existing theories and conceptions of ethnic identity it is worth noting that the problem of ethnic identity transformation in cross-national interaction in the context of psychological security has been given insufficient attention. Psychological security as a state of personality when a person can satisfy his basic need for self-preservation and his own (psychological) perceived security in a socium can act as the most significant predictor of mature ethnic identity.

Indeed, when people feel secure they are able to empathize with others, and, on the contrary, when they feel their existence in jeopardy they are likely to have lost the art of caring and sharing and to have difficulty in finding the meaning of their life. And identity statuses cannot only facilitate self-acceptance but also provoke lower self-esteem and poor self-confidence, a state of insecurity when they have absorbed negative social stereotypes of their ethnic groups.

A number of studies showed a link between identity statuses and a level of wellbeing (Seaton, Scottham, & Sellers, 2006), a level of depressive symptoms (Yip, Seaton, & Sellers, 2006), psychological adjustment and self-esteem (Rowley, Sellers, Chavous, & Smith, 1998). In other words, when ethnic identity is pronounced people with achieved identity, as a rule, state that they feel better being a member of their ethnic group and are psychologically secure. Therefore, one can assume, that with moving from one identity status to another, self-esteem, self-confidence and psychological security grow.

It should be noted that both security and identity are heavily mediated by the environment. In a poly-cultural region representatives of ethnic minority groups more often exhibit a risk of mental disorders (Cantor-Graae & Pedersen, 2013), vulnerability to discrimination, negative self-perception and social identity (Shaw et al., 2012). In this light, psychologists have been increasingly turning to social environment exploring specific features of life in regions with low and high ethnic diversity (Veling et al., 2008). The traditional culture of every region has a limited capacity to absorb new ethnic and migration flaws (Zotova, Tarasova, Perelygina, & Mostikov, 2018, p. 833). However, particularities of ethnic identity and psychological security in different residential environments have not been addressed so far.

It is of great importance to mention one more issue, namely, the significance and role of ethnic identity for a man. The thing is that psychological security, self-esteem and self-confidence can be based and connected with other types of identity (for example, gender, occupation, and so on). Nevertheless, an individual’ positive assessment of his/her ethnic group can be expected to have a positive link with psychological security only if this identity is central for his/her self-identification. The dominance of ethnic identity in the hierarchy of identities is interlinked with self-esteem (Rowley et al., 1998). Consequently, indicators of ethnic identity can provide a deeper insight into psychological security.

Problem Statement

The problem of ethnic identity from a perspective of a new line in domestic psychology – psychology of security – is one of significant scientific fields of theory and practice. The study of inter-ethnic relations gives a high profile to searching for relationships between personality psychological security and ethnic identity, perceived security and the state of security with behavior manifestation in inter-ethnic interactions as well as effective strategies to overcome situations bearing threats to personality psychological security and their realization in behavior patterns.

Research Questions

1. Is there a link between a status of ethnic identity and personality psychological security? If yes, what is it like?

2. Does a link between a status of ethnic identity and personality psychological security have specific features in regions with different degree of ethnic diversity?

Purpose of the Study

The study was aimed at examining specificity of interrelations between a status of ethnic identity and personality psychological security.

The following tasks were falling under the scope of this study:

1. to assess frequency of different statuses of ethnic identity within the sample groups from regions with varying degrees of ethnic diversity;

2. to reveal absence/presence of a linkage between a status of ethnic identity and personality psychological security within the sample groups from regions with varying degrees of ethnic diversity;

3. to define interrelations of content-based aspects of ethnic identity status and personality psychological security within the sample groups from regions with varying degrees of ethnic diversity.

Research Methods

Subjects

In order to define regions for the study the analysis of ethnic diversity of the RF regions was conducted. The officially published statistical data were used in the analysis. The considered indicators included figures of population by nationality in the constituent entities of the RF, i.e. a criterion of ethnic diversity was the population’ belonging to ethnic groups. To quantify ethnic diversity, we used the Simpson diversity index applied to measure biodiversity. In our case it allowed us to assess a degree of possibility that two randomly selected representatives of the region will belong to two different ethnicities. 85 regions of the RF were included in the analysis. A summary evaluation of every region was made through creating regional rankings according to Simpson’s index. It resulted in defining two regions for the study: the Sverdlovsk region (diversity index – 0.263540) as a territory with average ethnic diversity and the Republic of Bashkortostan (diversity index – 0.730376) as a highly diverse region in terms of ethnicity.

In order to ensure that a sample from each region is representative and exactly reflects the sampling universe – the structure of population by gender, age, education and type of settlements sample frames in each region were defined on the basis of regional demographic data. The percentage of every group of population was calculated (by gender, age, education, type of settlements). The quota sample of the Sverdlovsk region constituted 512 people and that of Bashkortostan – 508 persons.

Measures and tools

The study heavily relies on the approach offered by Yip (2014). According to this work status determination is produced on the basis of correlating the intensity of identity parameters measured by J. S. Phinney’ method – search for ethnic identity and commitment. In line with the study results diffuse identity is defined by the combination of low intensity of identity search and low degree of commitment; foreclosed identity – low search and moderate commitment; moratorium – high search for identity and moderate commitment; achieved identity – high identity search and high commitment.

– The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure (MEIM) Phinney (1992), an instrument assessing affiliation with ethnic groups;

– The scale “Satisfaction with Need for Security” by O. Yu. Zotova (Zotova et al., 2018).

The data obtained were processed with the use of descriptive statistics methods, Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient, and regression analysis. The results were further analyzed via SPSS 20.0.

Findings

At the first stage of the study a comparative analysis of frequency of ethnic identity statuses in the quota samples of the respondents from the region with high identity diversity (n1 = 508 persons) and average ethnic diversity (n2 = 512 people) (table

Therefore, the representatives of the region with high ethnic diversity are characterized by a clearer ethnic self-determination. Just 24% of the sample has not questioned their ethnicity, and a sense of belonging to an ethnic group is either absent (3%), or is determined by external circumstances (21%), while the percentage of the same group in the region with average ethnic diversity makes up 40%. In other words, under ethnic diversity, a great number of ethno-differentiating indicators accompanying inter-ethnic interaction and providing possibilities to relate to various ethnic groups ethnic awareness acquires emotional and cognitive clarity.

In order to establish the existence and nature of a link between personality psychological security and its ethnic identity status two-dimensional scattering graphs for each of the groups were produced.

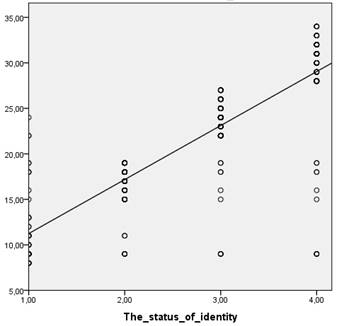

According to the data obtained the status of ethnic identity and personality psychological security in the region with average level of ethnic diversity has the linear relationship (figure

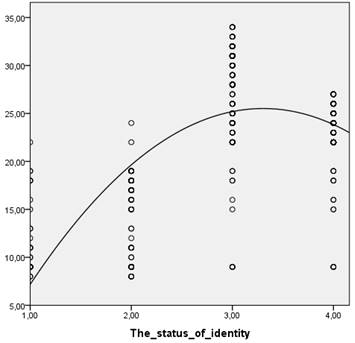

In the region with high level of ethnic diversity the relationship under consideration is of non-monotone, curvilinear character (figure

Therefore, there is a significant link between personality psychological security and ethnic identity status. However, the established link changes its character due to external parameters – the degree of the environment ethnic diversity.

Further analysis was devoted to the examination of the relationship of content-based aspects of ethnic identity status (search for identity and commitment) and personality psychological security in the groups of the respondents from the region with high identity diversity and average ethnic diversity.

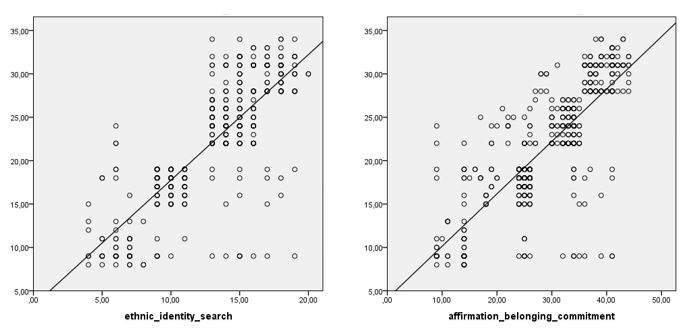

The revealed significant direct relationship (r = 0.791, where р = 0.000) testifies to the fact that in the region with moderate ethnic diversity with the advancement of personality psychological security there is a growing awareness of one’s ethnicity, interest in learning more about one’s ethnic group, its history, traditions, customs (figure

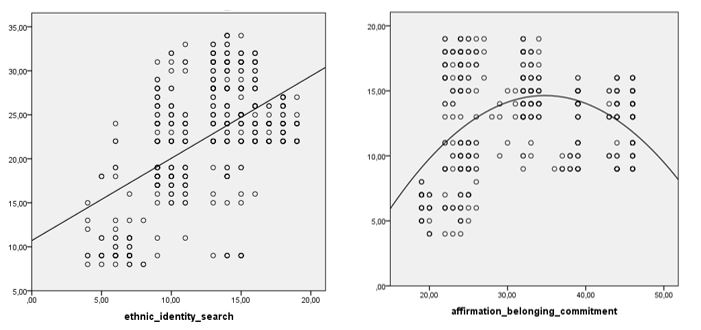

In the region with high level of ethnic diversity the character of the relationship between search for ethnic identity and psychological security is the same as in the region with average level of ethnic diversity (r = 0.531, where р = 0.000). Thus, we can conclude that ethnic identity search, awareness of one’s ethnic belonging positively correlate with personality psychological security irrespective of the milieu ethnic diversity (figure

At the same time one can note curvilinearity of the relationship of personality psychological security and the degree of one’ commitment to ethnic group in the sample from the region with high level of ethnic diversity: it has the well-pronounced maximum, and upon moving to the graph’ borders the diminishing variable “commitment” is observed. Statistical criteria exploited in the following analysis indicated the quadratic relationship between the given variables (R2 = 0.584). And low value of р (р = 0.003) is indicative of statistical reliability of the results obtained. Thus, in the region with high level of ethnic diversity a high degree of personality psychological security is connected with moderate commitment to one’s ethnic group.

Conclusion

The carried-out study has allowed us to examine one of the aspects of ethnic identity transformation in the process of inter-ethnic interactions in the Russian society and to consider the relationship between psychological security and personality ethnic awareness, its social conditionality.

First, it has been established that in the regions with varying degrees of ethnic diversity the allocation of ethnic identity statuses is of different character. So, the respondents from the region with average level of ethnic identity heavily exhibit statuses of foreclosed identity or moratorium while the subjects from the region with high level of ethnic diversity hardly demonstrate a status of diffuse identity, and statuses of moratorium and achieved identity are widespread. One can assume that experience in immediate relating one’s self to people around by a great number of ethno-differentiating indicators produces a greater clarity of one’s identity status.

Second, a significant linkage between personality psychological security and ethnic identity status has been established. The nature of this relationship is mediated by specific features of personality residential environment. With moderate ethnic diversity of this environment this relationship has a linear character: with increasing status of ethnic identity psychological security also advances. When ethnic diversity is high this relationship acquires non-monotonous character: the respondents characterized by identity status “moratorium” demonstrate the highest psychological security while the respondents with diffuse, foreclosed and achieved identity have lower indicators of psychological security.

Third, it has been revealed that such a content-based aspect of ethnic identity status as ethnic identity search has a significant relationship with the degree of personality psychological security. With a growing awareness of one’s ethnicity, a desire to learn more about this ethnic group, personality psychological security also grows. And this characteristic does not depend on regional ethnic diversity: linearity of the relationship is preserved in both the region with high and low level of ethnic identity.

Fourth, the link of a content-based aspect “commitment” and personality psychological security has been found. This relationship is multi-dimensional and realized in different forms depending on specific ethnic diversity of personality residential environment. Thus, in the region with average level of ethnic diversity this relationship is linear: the stronger one’s commitment to ethnic group is, the more advanced personality psychological security. In the region with high level of ethnic diversity a stronger commitment does not cause a higher degree of psychological security, and the highest psychological security is observed in the respondents with moderate commitment to one’s ethnic group.

Therefore, empirical results emanating from the study allow us, to some degree, to clarify some aspects of ethnic identity transformation occurring in the context of poly-ethnic, cross-national interactions. Of great promise are further studies into the relationship between ethnic identity status and the degree of its psychological security with the participation of different groups of the respondents: not only from regions with varying levels of ethnic diversity but also from regions representing a dominant ethnic group and ethnic minority.

Acknowledgments

The article was supported with a grant from the Russian Science Foundation (project № 18-18-00112.

References

- Al-Issa, I. (1997). The Psychology of Prejudice and Discrimination. In I. Al-Issa & M. Tousignant (Eds.), Ethnicity, Immigration, and Psychopathology (pp. 17-32). New York: Plenum Press.

- Cantor-Graae, E., & Pedersen, C. B. (2013). Full spectrum of psychiatric disorders related to foreign migration: a Danish population-based cohort study. JAMA Psychiat., 70, 427-435.

- Erikson, E. (1968). Identity: Youth and Crisis. New York: Norton.

- Koneru, V. K., Weisman de Mamani, A. G., Flynn, P. M., & Betancourt, H. (2007). Acculturation and mental health: Current findings and recommendations for future research. Applied and Preventive Psychology, 12(2), 76-96.

- Phinney, J., & Ong, A. (2007). Conceptualization And Measurement Of Ethnic Identity: Current Status And Future Directions. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 54(3), 271-281.

- Phinney, J. S., & Kohatsu, E. L. (1997). Ethnic and Racial Identity Development and Mental Health. In J. Schulenberg & J. L. Maggs (Eds.), Health Risks and Developmental Transitions During Adolescence (pp. 420-443). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Phinney, J. S. (1989). Stages of ethnic identity in minority group adolescents. Journal of Early Adolescence, 9, 34-49.

- Phinney, J. S. (1990). Ethnic Identity in Adolescents and Adults: Review of Research. Psychological Bulletin, 108, 499-514.

- Phinney, J. S. (1992). The Multigroup Ethnic Identity Measure: A new scale for use with diverse groups. Journal of Adolescent Research, 7(2), 156-176.

- Phinney, J. S. (1993). A three-stage model of ethnic identity development in adolescence. In M. E. Bernal (Ed.), Ethnic identity: Formation and transmission among Hispanics and other minorities. SUNY series, United States Hispanic studies (pp. 61-79). New York: State University of New York Press.

- Rowley, S. J., Sellers, R. M., Chavous, T. M., & Smith, M. A. (1998). The relationship between racial identity and self-esteem in African American college and high school students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(3), 715-724.

- Seaton, E. K., Scottham, K. M., & Sellers, R. M. (2006). The Status model of racial identity development in African American adolescents: Evidence of structure, trajectories and well-being. Child Development, 77(5), 1416-1426.

- Sellers, R. M., Rowley, S. A. J., Chavous, T. M., Shelton, J. N., & Smith, M. A. (1997). Multidimensional Inventory of Black Identity: A preliminary investigation of reliability and construct validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 805-815.

- Shaw, R. J., Atkin, K., Bécares, L., Albor, C., Stafford, M., Kiernan, K. E., … Pickett, K. E. (2012). Impact of ethnic density on adult mental disorders: narrative review. Br. J. Psychiatry, 201, 11-19.

- Thoits, P. A. (1995). Identity-Relevant Events and Psychological Symptoms: A Cautionary Tale. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 36, 72-82.

- Torres, L., Driscoll, M. W., & Voell, M. (2012). Discrimination, acculturation, acculturative stress, and Latino psychological distress: A moderated mediational model. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology, 18, 17-25.

- Veling, W., Susser, E., van Os, J., Mackenbach, J. P., Selten, J.-P., & Hoek, H. W. (2008). Ethnic density of neighborhoods and incidence of psychotic disorders among immigrants. Am. J. Psychiatry, 165, 66-73.

- Yip, T. (2014). Ethnic Identity in Everyday Life: The Influence of Identity Development Status. Child Development, 85(1), 205-219.

- Yip, T., Seaton, E. K., & Sellers, R. M. (2006). African American Racial Identity Across the Lifespan: Identity Status, Identity Content, and Depressive Symptoms. Child Development, 77(5), 1504-1517.

- Zotova, O. Yu., Tarasova, L. V., Perelygina, E. B., & Mostikov, S. V. (2018). Ethnic Identity of Teenagers and the Need for Security. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, XLIX, 832-840.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 July 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-063-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

64

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-829

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Zinchenko, Y. P., Zotova*, O. Y., & Tarasova, L. V. (2019). The Status Of Ethnic Identity And Psychological Security Of Personality. In T. Martsinkovskaya, & V. R. Orestova (Eds.), Psychology of Subculture: Phenomenology and Contemporary Tendencies of Development, vol 64. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 799-808). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.07.104