Abstract

The present study explores values of sport and non-sport students. The sample includes 122 students. The respondents were divided into four groups, three of which consisted of students of the Institute of Physical Education, Sport and Health and one group consisted of non-sport participants. We hypothesized that in the group of athletes the Achievement and Stimulation values would be more preferred then in group of non-athletes. The Russian version of the S. Schwartz Portrait Values Questionnaire was used to measure value orientations of students. The hierarchical structure of values varies among four groups of students. In the group of athletes-medalists the most important values are Benevolence, Achievement, Hedonism. In the group of athletes who have not yet received awards the most important values - Achievement, Self-Direction, Universalism. In the group of sports university students, but not athletes, the values of Benevolence, Conformity, Universalism are most preferred. For non-sport students, the more preferred values were Self-Direction, Hedonism and Benevolence. A most interesting group consists of students of the Sports Institute, who do not have awards or serious sports experience, but are involved in sports. Their value preferences are not similar to the results of professional athletes nor to the results of non-sport students who are not involved in sports. This group consists of young people who more prefer Conformity value and less prefer Achievement, Hedonism and Stimulation then the other participants of the study.

Keywords: Athletesnon-athletespersonal values

Introduction

Values are a set of attitudes in various areas of life, such as religion, morality, politics, work, etc. They perform the functions of standards or criteria, determine the choice or assessment of actions, behaviour, people and events. We decide whether actions, events, other people are good or bad, what it makes sense to do and what to avoid, based on whether it helps bring closer or, conversely, postpones the achievement of desired values (Karandashev, 2009; Schwartz, 2003).

Schwartz gave the following definition of values: these are cognitive representations that relate to a person’s desired state or behavior. In contrast to specific goals, the values are trans-situational, that is, they are not limited to specific situations. Values serve as a guide for selecting and evaluating behaviour or events and are ordered by relative importance (Rokeach, 1973; Schwartz, 1992; Schwartz & Bilsky, 1990). Value preferences are closely associated with various psychological characteristics, in particular, with self-relation and self-esteem (Tikhomandritskaya, 2000), with subjective well-being and life satisfaction (Schwartz & Sortheix, 2018).

Social experience is one of the main sources influencing the formation of differences among individuals in value preferences. The general experience that people receive due to the fact that they have a similar position in a social group (due to age, occupation, education, etc.) influences their value priorities. Consequently, if we compare the values of certain groups of people, then we can demonstrate the impact of social factors (for example, education), as well as specific events (for example, diseases) on the development of a system of values (Schwartz, 2003).

Problem Statement

Studies of the values of athletes are of particular interest. This is due to the fact that professional and amateur sports involve a well-developed commitment, ability to work in a team, stress resistance. Psychological analysis of sports activity shows that it manifests a variety of aspects of personality, including socio-psychological.

Thus, in a large study carried out in Hungary, a comparison was made between young people involved in sports and those not involved in sports (Perényi, 2010). It was found that sports are negatively correlated with the preference for materialistic values, such as power, wealth, money, and positively correlated with such values as true friendship, creativity, free time, diverse life. In a study conducted in Lithuania, it was found that young people involved in sports appreciate the value of achievement, hedonism, self-regulation, stimulation, conformity and security higher than young people not involved in sports (Daukilas, Kovalčikienė, & Balakienė, 2017).

Research Questions

We assumed that in the group of athletes the value Achievment would be more preferred then in group of non-athletes. Due to the fact that professional sports are often associated with risk, we also hypothesized that the value Stimulation would be evaluated by athletes higher than by non-sport students.

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the study was to analyse value preferences of athletes and non-sport students and to compare the value orientations for different groups of sport students.

Research Methods

Sample

The participants of the study were 122 students. The respondents were divided into 4 groups, 3 of which consisted of students of the Institute of Physical Education, Sport and Health (Sports Institute):

Group 1 (medalists) – athletes-students of the Sports Institute, who have won competitions.

Group 2 (non-medalists)- athletes-students of the Sports Institute, who did not have awards and achievements, but have sports experience.

Group 3 (sport students) - students of the Sports Institute, who do not have sports experience. It is important to note that such students are not obliged to go into sport as their specialty can be in sports management or psychology. However all students attend classes devoted to different kind of sports together.

Group 4 (non-sport students) - included respondents from other universities not related to sports.

The age and gender descriptive statistics for each group is presented in Table

Methods

The Russian version of the Schwartz Portrait Values Questionnaire was used to measure value orientations of students (Magun & Rudnev, 2008; Schwartz, 2003). The questionnaire consists of 21 descriptions of individuals that correspond to “first level” values. “Second level” values—typological value indexes—are calculated by adding up the “first level” values. Second-level values include Security, Conformity, Tradition, Self-Direction, Stimulation, Hedonism, Achievement, Power, Benevolence, and Universalism. Third-level values are aggregated second-level values and include Conservation (Security, Conformity, and Tradition), Openness to Change (Self-Direction, Stimulation, and Hedonism), Self-Enhancement (Achievement and Power), and Self-Transcendence (Benevolence and Universalism).

Findings

The hierarchy of values in groups of athletes and students without sports experience

Table

The hierarchy of values in different groups differs (see Table

Differences are observed when choosing the least significant values. For athletes who have achieved awards the least important are Stimulation, Conformity and Tradition; for those athletes who have not yet received awards, Security, Conformity and Tradition are least preferred values; for students of the Sports Institute, but not athletes, Hedonism, Achievement and Stimulation are the least important values; for non-sport students - Power, Tradition and Conformity.

The most interesting is to compare the value preferences of athletes-medalists and non-medalists. It is quite clear that those athletes who did not receive awards put the value of Achievement in the first place, whereas for athletes who already have achievements, the significance of this value decreases. The lack of sporting achievements is also possibly due to the differences in rank of the value of Hedonism - those who have not yet reached the top places are more inclined to limit themselves to desires. A special group consists of respondents - students of the Sports Institute who are not sportsmen. Unlike all other groups (and even groups of non-sport students), achievements are completely unimportant for them, but Conformity is a significant value. Moreover, only for these respondents, the Power value has a higher rank position compared to other groups.

The ranks of the third-order values also differ depending on the group of respondents (see Table.

Cross-group differences in the assessment of basic values

ANOVA variance analysis was used to compare the estimates for each value. Ratings of each value were selected as a dependent variable; categorical predictor is certain group of respondents.

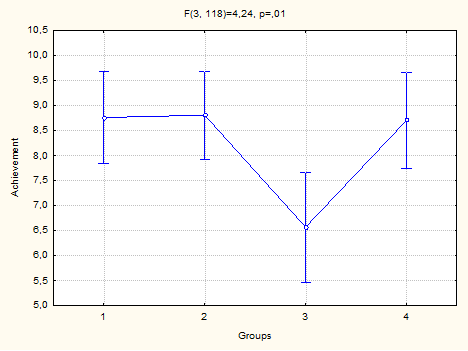

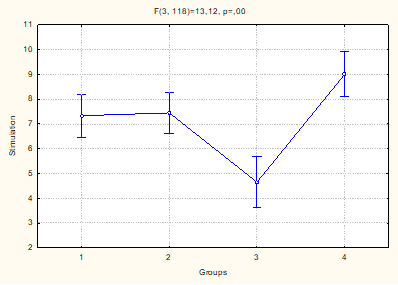

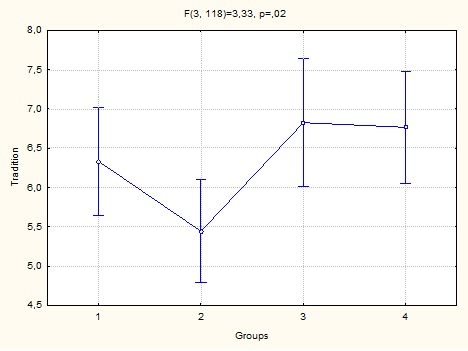

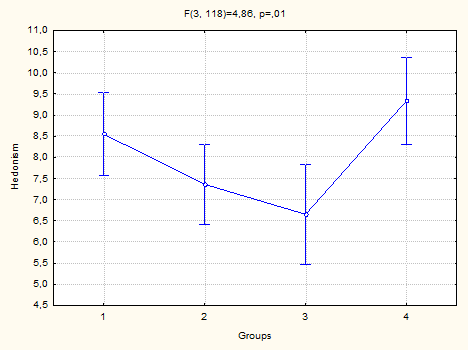

It is most interesting to consider differences for values of Achievement, Stimulation, Tradition and Hedonism.

For value Achievement, contrary to our assumption, there is no difference between groups of athletes-medalists, athletes who have not received awards, and non-sport students. However, there are differences with the group of students of the Sports Institute - they rate Achievements significantly lower than the other three groups (Figure

Stimulation values were awarded the highest scores in the group of non-sport students (Figure

The value of Tradition has the lowest level in group of athletes who have not yet have reached awards (Figure

In this group also, in comparison with other groups, the value of Benevolence was estimated lower (comparison with a group of athletes of medalists F = 8,68; p = 0,00; comparison with a group of students of the Sports Institute F = 7,08; p = 0,01; comparison with a group of non-sport students F = 11,27; p = 0,00). The reason for these differences may be that in a group of athletes who do not yet have sport achievements, the value of friendship or caring for others is temporarily reduced because of the desire to receive an award. Another explanation is that such differences are an artifact. In our work, we did not set a goal to divide athletes according to the sport, but there is a possibility that the group of athletes who have not yet received awards, for the most part consists of athletes of aggressive sports, such as Boxing.

As for the value of Hedonism, non-sport students and sportsmen-medalists estimate this value most highly (Figure

Also, differences were obtained for the value of Conformity, the most significant is this value for students of the Sports Institute (differences with a group of athletes-medalists F = 3,91; p = 0,05; differences with a group of athletes who have not received awards F = 12,27; p = 0,00; differences with a group of non-sport students F = 7,31; p = 0,01). All other respondents rate this value significantly lower.

The result of our study does not agree with the data presented in the study by Daukilas et al. (2017). In a Lithuanian study, the value orientations of people involved and not involved in sports were compared. It was found that athletes have higher levels of such values as Achievement, Hedonism, Stimulation, Self-Direction, Conformity and Security. In our sample, the athletes did not differ in the choice of values from the group of non-sport students; moreover, in terms of the Stimulation value, the students’ ratings exceeded the athletes' estimates. The reason for the discrepancy between the results may be that our sample is more heterogeneous in composition and includes both athletes who won international or regional competitions, as well as non-sport students who are either not related to sports or who have no sports ambitions. In a study conducted in Lithuania, young people actually involved in sports and not involved in sports were compared, while in our study, the group of athletes was divided into subgroups depending on their sport achievements.

Conclusion

1. The hierarchical structure of values varies among athletes-medalists, athletes who do not have awards, students of the Sports Institute and non-sport students. For athletes-medalists the most preferred values are Benevolence, Achievement, Hedonism. In the group of athletes who have no awards, the values of Achievement, Self-Direction, Universalism are most significant. The values of Benevolence, Conformity, Universalism are important in the group of students of the Sports Institute who have no awards and sports experience. Non-sport students most highly rate Self-Direction, Hedonism, Benevolence.

2. Non-sport students have higher level of Stimulation than athletes. Athletes who have not yet received awards, less prefer values of Tradition and Benevolence.

3. A separate most interesting group consists of students of the Sports Institute, who do not have awards or serious sports experience, but are involved in sports. Their value preferences are not similar to the results of professional athletes, nor to the results of non-sport students who are not involved in sports. This group consists of young people who more prefer Conformity value and less prefer Achievement, Hedonism and Stimulation then the other participants of the study.

Limitation

The analysis of the results did not include the gender of the respondents, as well as the sport they are engaged in.

References

- Daukilas, S., Kovalčikienė, K., & Balakienė, L. (2017). Hedonic and eudaimonic values in sport participation of the youth. Management Theory and Studies for Rural Business and Infrastructure Development, 39 (4), 409–420. https: //doi.org/

- Karandashev, V.N. (2009). The concept of cultural values of Sh. Schwarz. Questions of Psychology, 1, 81–96. [in Russian]

- Magun, V., & Rudnev, M. (2008). Vital values of the Russian population: similarities and differences in comparison with other European countries. Journal of Public Opinion, 1(93), 33–58.

- Perényi, S. (2010). The relation between sport participation and the value preferences of Hungarian youth. Sport in Society, 13(6), 984-1000. https: //doi.org/

- Rokeach, M. (1973). The nature of human values. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Schwartz, S.H. (1992). Theoretical advances and empirical tests in 20 countries. In M.P. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in experimental social psychology (pp. 1-65). San Diego, CA: Academic Press

- Schwartz, S.H. (2003). A Proposal for Measuring Value Orientations across Nations. European Social Survey, 7, 259–319.

- Schwartz, S.H., & Bilsky, W. (1990). Toward. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 58(5), 878–891.

- Schwartz, S.H., & Sortheix, F.M. (2018). Values and subjective well-being. In E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of well-being (pp. 1-16). Salt Lake City, UT: DEF Publishers.

- Tikhomandritskaya, O.A. (2000). Values and self-attitude at the stage of youth socialization (Doctoral Dissertation). Moscow: Moscow State University. [in Russian]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 July 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-063-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

64

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-829

Subjects

Psychology, educational psychology, counseling psychology

Cite this article as:

Alekseeva, O., Fominykh*, A., Rzhanova, I., Clavelo, A., & Korshunov, A. (2019). Personal Values Of Athletes And Non-Athletes. In T. Martsinkovskaya, & V. R. Orestova (Eds.), Psychology of Subculture: Phenomenology and Contemporary Tendencies of Development, vol 64. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1-9). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.07.1