Abstract

The term 'well-being', a central concept in psychology and education, relates to various aspects of the way one feels and acts, and has been gradually recognized as an important feature in educational systems in recent years. It includes the sense of self-efficacy, internal motivation for action, autonomy, creativity, positive worldview, social involvement and leadership, and is closely related to the definition of happiness. This paper focuses on the unique contribution of anart workshop in high-school, which is created in a way that allows students to experience processes designed for enhancing their well-being – in its wider sense. The paper relates to several theoretical dimensions that serve as a basis for the development of this art workshop, including links between art and education and humanistic pedagogic theories. It focuses on ways of fostering creative thinking and creativity but also emotional intelligence and dialogue in multicultural contexts, especially among adolescents. It addresses the ways this art workshop aims to promote 'meaningful learning', i.e., a learning process that allows students to enrich their knowledge and develop their professional skills while encountering their internal world. The rationale is that such an encounter has a significant impact on their well-being, and thus, taken together, the paper describes how the art workshop allows meaningful learning and consequently contributes to the students' well-being. The author is a teacher in an art workshop and is currently researching the narratives of graduates concerning the impact of their studies in the workshop on their well-being and their development as adolescents.

Keywords: Art educationArt workshopwell-beingadolescencemeaningful learning

Introduction

Participating in an art workshop during high-school can have an extremely significant effect on adolescents’ development and mental well-being. The activities in such a workshop are part of the curriculum in art education. The students are experimenting many different techniques of painting and sculpturing, while also learning art history. The curriculum extends over three years of learning (grades 10-12), culminating in a final project on a personally-chosen subject in grade 12. Before graduation, the final projects of the students are presented in a group exhibition, alongside a position paper outlining the background and rationale of the project (Figure

Main Body

Art and education

What is the function of art in education? What is the definition of well-being? How can an art workshop contribute to the well-being of high school students? In this paper, the writer will try to enhance the understanding of the potential contribution of the learning process in an art workshop to students’ well-being in general, particularly during the stormy period of adolescence.

Education systems tend to focus on scientific disciplines. However, art education should receive a much more serious focus, alongside or even combined with scientific fields. Since the dawn of Western civilization, art studies have been a central component in the development humanity. In the classical period, in the days of ancient Greece and Roman Empires, members of the upper class were able to study art. During the Middle Ages, the focus shifted due to the belief of man being small and insignificant compared to God, but humanism regained its revival during the Renaissance, a period known for placing humanity back in the center, and therefore also art.

Artists who were considered Renaissance Men, like Leonardo da Vinci or Michelangelo, were interested in both art and science: Innovations, painting, sculpturing, architecture, music, mathematics, engineering, literature, anatomy, geology, astronomy, botany, writing, history, cartography – all were important, all worth exploration. Therefore, they were considered to be Universal Geniuses – a term that describes an educated person with extensive and in-depth knowledge in many fields of science and culture. Modern education systems must restore the missing spiritual dimensions of education if they strive to produce graduates who are whole – people who draw inspiration from the Renaissance in their development. The study of the world and of humankind must be combined while giving place for individuals – their emotions and spiritual life. This humanistic approach place significance on the emotions and spiritual life of the students as part of their learning processes. The current paper aims to enhance the understanding of the importance of art education and the art workshop's processes in containing emotions, and allowing students to express and process emotions and sensations.

Education needs art: Five approaches in art education

1.Art education as a technical skill: Two hundred years ago, the question of the need for art education for all students was asked, despite the knowledge that most of them would not engage in art in their adult lives. Schools adopted the academic approach, with workbooks containing drawings that the students were asked to copy, and drawing and painting of still life that was placed before the students in class. Some schools adopted the approach of the Swiss educator Johann Heinrich Pestalozzi (born in the 18th century). His method, aimed at working-class students, focused on teaching geometric elements – straight and rounded lines – using similar methods to those used in geometry classes (Efland, 1990). Both the academic approach and Pestalozzi highlighted the technical aspect of art, which became rather redundant with the invention of the camera and the computer (Cohen-Evron, 2012).

2. Art education as a creative self-expression: The creative self-expression approach, which emphasizes creativity, originality and personal interpretation, has emerged as the goal of art education in the first half of the 20th century. This approach aspired to free itself from common language, thinking and behavior patterns, and saw the essence of artistic education in the process of creation rather than in its products. Learning in this approach enable students to experience a variety of materials and expressing their own imagination, understanding and personal experiences. Teachers allow students to work without supervision and give them freedom to define their own personal actions and solutions. Herbert Reed and Viktor Lowenfeld led this approach in the 1940s. Reed argued that artistic activity is essential for every child as means of promoting and expressing their development and should therefore be the basis for any educational action (Reed, 1943; Postman, 2000). Lowenfeld, who based his approach on Freud's psychoanalytic theory, explained that artmaking was essential for healthy physical and mental development (Lowenfeld, 1947). Such views are consistent with Dewey's progressive path, emphasizing the importance of experiential learning, which expresses and enriches the student's emotional world (Efland, 1990). Studies from the 1990s proved that artistic expressions of adolescents enable them to find their own place in school, thus improving their feelings in the learning environment and school climate as a whole (Fiske, 1999).

3. Art education as cognitive creative activity: Rudolf Arnheim and Elliott Eisner referred to creativity as a cognitive process of creative thinking and problem solving at a high level (Arnheim, 1969; Eisner, 2002). The process of creation as a problem-solving process has served as the basis for new approaches to art education. Based on this approach, students performed exercises based on visual and material language and learned to think, create and understand works of art. These days, when creativity is required in all areas of life and is considered a central goal in the educational process, the ability to dare, err, imagine and create plays an important role in schools. According to Eisner (2002) and Steers (2009), artistic activity contributes to the development of creative thinking, and each stage of the artistic process promotes the development of creative abilities.

4. Art education through an encounter with works of art: In addition to the importance of artistic activity, the exposure of students to works of art is also important. According to Cohen-Evron (2012), consistent observation, discourse and appreciation of works of art was a common practice in 18th and 19th century schools. These activities were a central component of art education according to the Discipline-Based Art Education (DBAE) approach, developed in the 1960s. Accordingly, the theoretical, critical and interpretive discourse is an essential part of art education. It is possible to discuss a variety of works in the context of many issues, questions, attitudes and meanings (Cohen-Evron, 2012). Art is seen as a source of meaning that any observer can experience and discover in any artwork (Dobbs, 2004)

5. Art education as a visual culture: This is an innovative approach to art teaching, in which students are perceived as consumers of culture. It views art as an inseparable part of the cultural complex. Objects or visual images are perceived as visual texts that can be interpreted in a wide range of meanings. Images can be seen in any type of media: Computer, television, or smartphones, inviting interpretation and response. This approach examines these sites critically, highlighting the importance of studying the images in various media in light of their centrality and larger influence. Baudrillard (1997) addressed artworks not as representing reality but as part of reality itself. Art education in this approach focuses on the social mechanisms that form the visual field and its visual structure (Mitchel, 2005). This learning processes adopt critical thinking about the reality on screens, which has become the reality of students' lives. Since students spend much of their time in front of the screens, it is important to cultivate critical thinking about the virtual – or rather, real – reality of their lives. Critical reading of visual images is necessary and must be emphasized as a subjective interpretation (Cohen-Evron, 2012; Read, 1943).

Well-Being

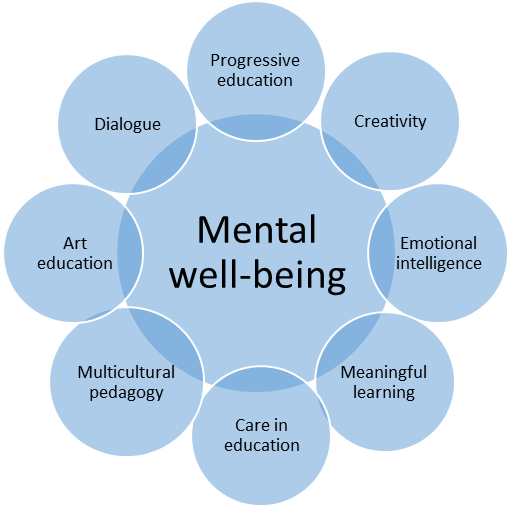

The concept of well-being includes the sense of self-efficacy and an optimum level of functioning and is considered close to the definition of happiness. Well-being is reflected in a wide range of features including internal motivation for action, autonomy, ability, initiative, choice, flexibility, creativity, positive worldview, finding meaning, interpersonal relationships, social involvement and leadership. The school art workshop is one of the places that allows the students to experience processes designed for enhancing their well-being. The contribution of the art workshop to the well-being of high school students during adolescence can be better understood through other pedagogical theories that accompany the art education approaches and support an educational process that promotes well-being (Cowen, 1994; Diener, 2000; Diener, Lucas, &Schimmack, 2008; Myers, 2000, Zimerman, 2010).

Humanistic Pedagogic Theories

The first link of the pedagogy chain that inspires the activity in the art workshop is the Progressive Education approach (Dewey, 1902; Piaget, 1926; Rogers, 1951). Progressive Education was developed as a reaction to the traditional style of teaching. It is a pedagogical movement that values experience over memorizing. The next link in the chain is the theory of Emotional Intelligence and Emotional Management (Goleman, 1997). Emotional intelligence (EI) is the capability of individuals to recognize their own and other people's emotions, distinguish between different feelings and label them appropriately, use emotional information to guide thinking and behavior, and manage and/or adjust emotions to adapt to environments or achieve one's goal. Gardner (1983, 1996, 2008) presented the theory of Multiple Intelligences in class, claiming that intelligence is not a single, static IQ number, but rather a dynamic collection of skills and talents that are manifested differently in different people. The Multicultural Pedagogy (Banks & Banks, 2005) adds to this pedagogic chain. It is based on the assumption that it is possible to influence the educational and emotional progress of a variety of ethnic, racial, and social groups within educational frameworks that acknowledge their culture.

According to the Curriculum for Human Beings (Greene, 1993), when we are aware of the existence of diverse populations, with different preferences and values, we come to understand that there can be no single standard of humanity, achievement or ownership in looking at the world. Greene argued that curricula and pedagogy should not silence or blur differences between students. The Border Pedagogy (Giroux, 1995) suggests that the educational space is a place where teachers and students can re-examine the relationship between center and periphery in the power structures of their personal lives and collective lives as a cultural group. These processes require them to be liberated from false ethos; they should employ critical criticism, and a sensitive and profound understanding of variances that include symbolic codes of cultures and histories, alternative languages, and many different life experiences. Border pedagogy often expresses crisis points in the meaning of the curriculum for teachers and students.

The Pedagogy of Caring (Noddings, 2003, 2005) offers a new perspective on all aspects of education – defining teaching as one of the "caring professions", and the goals of teaching should change according to the learner's needs. Csíkszentmihályi (1999) emphasizes the importance of internal motivation (task involvement) to meaningful learning, as opposed to external motivation (ego involvement), and highlights the state of flow – a state that characterizes people in their most creative moments. Accordingly, internal motivation requires five human basic needs to be met: connection, belonging, self-efficacy, freedom and purpose. Internal motivation leads to self-fulfillment. Another aspect of meaningful learning is the independent learning approach (Mitra, 2006). Mitra advocates the independent learning approach, which he termed Minimally Invasive Education. Education in the 21st century should create, according to Mitra, a "curriculum of great questions". The teacher should not interfere with the direction or content of learning, but rather encourage and support the students. Teachers should not make learning happen, but rather should allow it to develop. They start the process, and then stand back and watch as the learning takes place (Harpaz, 2008).

According to Robinson (2013), in creative thinking we need to think differently about ourselves and act differently toward each other. We must learn to be creative. Aloni (2014) adds another link to the academic chain the Dialogue in Humanistic Education, defining dialogue as a kind of shared learning of the world, a natural process which does not necessarily have clear products. A dialogue is a conversation that engages those who are involved in themselves and interested in others, both in terms of their common humanity and their unique personality; it is based on trust, respect, openness and mutual attention of members who aspire together to a better and more comprehensive understanding of themselves and others. According to Aloni, educational activity is based on a rich repertoire of dialogues that can help teachers in developing students' awareness and abilities, and empower their ability to lead a full, autonomous, decent, dignified life of life.

All of the above theories interact with and affect well-being (see Figure

Methodology

The planned research will be conducted using mixed methods, including both quantitative and qualitative techniques. Its goal is to examine the effects of an art workshop on the well-being of high school students in Israel during adolescence.

The research question is: What is the contribution of the art workshop to the development of well-being of adolescent students in high school?

The research tools are: In-depth semi structured interviews with the program’s graduates, text analysis using pictures of final projects, position papers written by the students during their work, questionnaires assessing well-being.

Conclusion

The literature about adapted pedagogy to high school students in the 21st century is rich and diverse. Art studies have been a key dimension of humanistic education since the Classic Period, thus the mere teaching in the art workshop is not an innovative pedagogy in itself. Yet, if applied thoughtfully and sensitively it can yield deep processes of meaningful learning, from which every student can benefit a lot. In my view, art education must be part of our lives. As phrased by Frogel (2012):

"Art education must be a central element in the basic education process of every child, from kindergarten to high school, and the importance of art trends and their vitality for the development of a worthy social and cultural life in Israel must be recognized." (pp. 46-47)

The current paper elaborated about various aspects of art education and the processes involved in it, emphasizing the centrality of students’ well-being. The paper can also help in raising the awareness of education policy makers to the importance of art education alongside sciences, English and mathematics, which are essential for the professional development of students. Students who experience well-being as teenagers have a better chance of succeeding in their studies and, most importantly, become happier adults.

In our current era, where screens dominate our lives, and have such an immense impact on internal processes and interpersonal relationships, it is highly important to cultivate students' emotional expressions and nurture their personal observation into the world – both internally, of their mind and soul, and externally, by looking thoroughly and critically at the outside world.

Acknowledgments

I am thankful to the graduates of the art workshop who shared their experiences with me

References

- Aloni, N. (2014). All that needs to be a person; A journey in educational philosophy, anthology. Tel Aviv: HakibbutzHameuchad and the Mofet Institute.[in Hebrew].

- Arnheim R. (1969). Visual thinking. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Baudrillard, J. (1997). Objects, images, and the possibilities of aesthetic illusion. In N. Zurbugg (Ed.), Jean Baudrillard: Art and artefact (pp. 7-18). London: Sage Publications.

- Banks, J. A., & Banks, C. A. M. (Eds.) (2005). Multicultural education: Issues and perspectives (5th ed). New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons.

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). 16 implications of a systems perspective for the study of creativity. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.),Handbook of creativity (pp. 313-335). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohen-Evron, N. (2012). Who needs art education anyway? HedHachinuch, 5, 56-59. [in Hebrew].

- Cowen, E. L. (1994). The enhancement of psychological wellness: Challenges and opportunities. American Journal of Community Psychology, 22(2), 149-179.

- Dewey, C. (1902). The child and the curriculum. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Diener, E. (2000). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness, and a proposal for national index. American Psychologist, 55, 34-43.

- Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., &Schimmack, U. (2008). National accounts of well-being. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Dobbs, S. (2004). Discipline-based art education. In E. Eisner and M. Day (Eds.), Handbook of research and policy in art education (pp. 701-724). Reston, Virginia: National Art Education Association.

- Efland, A. (1990). A history of art education. New York and London: Teachers College Press.

- Eisner, E. (2002). The arts and the creation of mind. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Fiske, E. (1999). Champions of change: The impact of the arts on learning. Washington DC: Arts Education Partnership.

- Frogel, S., Barchana-Lorand, D., Levy-Keren, M., &Barkai, S. (2012). On the importance of art education. Education, 5, 46-47. [in Hebrew].

- Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of the mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. UK: Hachette.

- Gardner, H. (1996). Multiple intelligences - theory in practice. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education and Culture &Branco Weiss Institute.

- Gardner, H. (2008). Art education and human development. Getty Publications, Los Angeles, CA.

- Giroux, H. A. (1995). Border pedagogy and the politics of postmodernism. In P. McLaren (Ed.), Postmodernism, post-colonialism and pedagogy. (pp. 37-64). James Nicholas Publishers.

- Goleman, D. (1997). Emotional intelligence; why it can matter more than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

- Greene, M. (1993). Diversity and inclusion: Toward a curriculum for human beings. Teachers College Record, 95(2), 211-221.

- Harpaz, Y. (2008). The third model: Teaching and learning in a thinking community. Tel Aviv: Hotsa'atPoalim[in Hebrew].

- Lowenfeld, V. (1947). Creative and mental growth; a textbook on art education. New York: Macmillan.

- Mitra, S. (2006). The hole in the wall: Self-organizing systems in education. New Delhi: Tata McGraw Hill.

- Mitchel, T. (2005). What do pictures want?: The lives and loves of images. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago.

- Myers, D. G. (2000). Wealth and well-being. In R. Stannard (Ed.), God for the 21st century (pp. 99-102). Radnor, PA: Templeton Foundation Press.

- Noddings, N. (2003). Caring: A feminine approach to ethics and moral education (2nded). Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Noddings, N. (2005). Caring in education. The encyclopaedia of informal education. Retrieved from: www.infed.org.il/biblio/noddings_caring_in_education.htm.

- Piaget, J. (1926). The language and thought of the child. New York: Harcourt Brace & Company.

- Postman, N. (2000). Approaches in art education. A Journal for Culture, Society and Education, 12, 14-9.

- Read, H. (1943). Education through art. London: Faber and Faber.

- Robinson, K. (2013). Out of the lines, the secrets of creative thinking. Jerusalem: Keter Books. [in Hebrew].

- Rogers, C. R. (1951). A way of being. Boston: Houghton Miffin Company.

- Steers, J. (2009). Creativity: Delusions, realities, opportunities and challenges. International Journal of Art & Design Education, 28(2), 126-138.

- Zimmerman, S. (2010). Mental wellbeing in the eyes of positive psychology. Tel-Aviv: Oah publishing. [in Hebrew

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Goldstein, A. (2019). The Greatest Benefit Of Art Workshop: Well-Being Literature Review. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 505-512). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.59