Abstract

Effectiveness and durability of the learning process are important goals for assuring a qualitative instruction. All the students want to be able to learn more efficiently (achieving the expected performance with less effort) and (more) sustainable (assuming knowledge, skills and resolute behaviours acquired through learning and leading it to the achievement of an appropriate performances). This goal could be attended through a facilitative teaching process, which uses the feedback as a factor which contributes to increased efficiency and sustainability of the learning process. Starting to this state of the art, we try to present some theoretical statement regarding the way in which the assessment process and the feedback could sustain a durable and effective learning. Also, using a questionnaire survey (with 20 items), we identified the opinions and beliefs of teachers form different educational level on how different formative assessment and feedback modalities influence the learning process and its efficiency. Identifying the influence of the feedback on stimulating students’ learning process on the future educational activities, we proposed some solutions for improving teacher training on formative assessment and feedback issues.

Keywords: Feedbackformative assessmenteffective and durable learningfacilitative teaching

Introduction

Teachers often ask themselves: how to determine their students to learn (more) effectively and (more) durably? One of the modality that teachers can use to stimulate effective and sustainable learning is the formative assessment. This type of assessment is considered an immediate and follow-up feedback on a teaching-learning sequence. It is also an assessment with a formative value (Black & Wiliam, 1998) having as objectives the attendance of a durable and effective learning and the usage of important strategies in the educational process (Black & Wiliam, 2009). The value of immediate formative assessment is that creates the opportunity to provide feedback during the learning process (Wiliam, 2011), immediately after each learning sequence.

The feedback becomes sometimes irrelevant if it is not accompanied by relevant comments or suggestions. These remarks could make the student aware of his learning performance’ level and suggest what he has to do to attend the progress of learning.

The confirmation feedback, the denial feedback (by correcting of an incorrect or wrong idea) especially the feedback provided by the teacher’s assessment contributes to an effective and sustainable learning. Hattie (2014) scientifically proved the effectiveness of feedback in achieving efficient and sustainable learning. Through an immediate formative assessment and consequent feedback students are challenged and determined to be engaged and to achieve the optimal performance in their learning process. Feedback can be offered in several ways and through different modalities and should valorise errors, mistakes and incorrect responses of the students as learning opportunities.

The feedback reduces the gap between the present state of the students’ learning performance (the level of the student’s learning in the evaluation process) and the expected stage (where the student’s level of learning "should" be) to sustain the learning process. In other words the gap between the current acquisitions of the students and the criteria for success is covered (Sadler, 1998; Hattie, 2014).

It is known that in their educational activities, teachers include a few feedback moments truly received by students. The frequency of providing feedback (whenever it is needed, at the right time and exactly what is needed for students’ progressing in their learning process) as well as how the students receive it are factors which contribute to the achievement of effective and sustainable learning.

Student’s feedback reception followed by a formative and immediate assessment helps them after to monitor their own learning and progress. The role of teacher’s feedback in the process of students’ self-regulation process is very important. It helps them to develop some specific self-regulation skills like the following: to compare the personal responses with the criteria of evaluation, to analyse the results compared with the initial objectives, to identify the personal leaning’ issues or to set up future objectives for optimize the learning process. For example, in the context of written work of the students, the feedback is understood as a facilitator for bidirectional communication and interpersonal communication between the teacher and the students and a motor that promotes the internal regulation of the student or the self-regulation of learning (Ion, Cano-García, & Fernández-Ferrer, 2017).

The key role of the evaluation process (especially the immediate formative assessment) is to support learning by generating feedback. The students could know where they are going, how they will get there and what else they can do for the future learning only receiving and understanding the teacher’s feedback (Hattie, 2014).

Problem Statement

The modalities for using the feedback to optimize the learning process (Shute, 2008), the conditions required which determine the feedback to be effective and useful (Sadler, 2010) and the ways in which students receive the feedback (Dunning, 2005) are every day challenges for teachers. These teachers accept and support the idea that the feedback and the immediate formative assessment could help students in optimizing the learning process.

The following studies will point the importance of teachers’ training sessions in using an effective and qualitative feedback in the educational process.

Regardless of the type of feedback used in the educational process (Task Feedback, Process Feedback or Self-Regulation Feedback) teachers should clarify the goal and the objectives of the lesson or activity, the way in which students understand the feedback and how they seek feedback from students about their teaching process (Hattie, 2016). They use the effective feedback as a considerable instrument for sustaining student’s self-regulation and preparation for lifelong learning.

It is very important to analyse the effective feedback through students’ perception on this issue. It is a common complaint from students regarding the assessment process: they do not receive adequate feedback and the process of giving and receiving feedback is rarely taught to students (Burgess & Mellis, 2015). Teachers should be aware of the importance of feedback in improving their learners’ knowledge, skills or behaviour. The goal is to reduce the gap between actual and desired students’ performance motivating the learners to attend the desired outcome. In this respect, teachers should assume some practical guidelines for providing feedback and take care about the students’ need for feedback. This could be done through some faculty training sessions which have a goal the development of feedback skills.

The effective feedback is considered a key strategy for the learning and teaching processes and for facilitating the students’ transition to a different educational level. It is necessary for developing and refining optimal learning students’ skills, but is frequently avoided, underused and poorly imparted (Wenrich, Jackson, Maestas, Wolfhagen, & Scherpbier, 2015). Faculty development can positively advance feedback skills for teachers as a base for understanding student’s developmental trajectory and needs, developing tools and strategies and adopting a dynamic, challenging and inclusive team approach teaching. Through these practices it will improve teachers’ evaluation skills and will be extended the feedback beyond the mode of delivery and its timeliness to the credibility of giving feedback (Poulos & Mahony, 2008).

Some tips for increasing skills in providing constructive feedback are necessary to be known and applied by teachers (Sargeant & Mann, 2017): viewing feedback as a positive activity and as a routine which improve learners’ performance and self-assessment; learning and improving the provision of feedback; assuring a certain time for observation and feedback; using specific feedback skills and participating in activities which offer support for improving personal feedback skills.

Teacher’s feedback on the writing practice needs some innovation because is product-based and form-based with several errors (Lee, Mak, & Burns, 2016). The difficulty in translating the feedback into practice consists in some principles acquired overtime by teachers. Also, the negative determination of many factors that assure the innovation of conventional feedback approaches in the writing classroom should be exceeded. It is important to identify how teachers’ education and teacher professional development can be improved to bring innovation in this issue.

The development of teacher’s feedback skills should also valorise the training on the written feedback through digital tools (Ion, Barrera-Corominas, & Tomàs-Folch, 2016). It is important to offer specific training sessions for teachers in using knowledge, strategies and methodologies for a relevant on-line feedback for improving student’s self-regulation skills and will assure a sustainable and effective learning. Acquisition of the art of providing feedback and the related skills helps teachers to sustain in a positive and effective way the students’ learning process. Leibold & Schwarz (2015) insist on the importance of providing online feedback for students through education, practice and faculty development.

So, teachers should be prepared for providing different types of qualitative feedback to students’. This need could be sustained by offering them evidence-based training workshops on how to provide quality constructive feedback to students (Richards, Bell, & Dwyer, 2017). The previously mentioned practical solutions for this issue will sustain the improvement of providing constructive feedback on students’ activity.

Research Questions

The theoretical fundaments previously mentioned in the article determined us to settled up the following research questions:

What is the importance of the feedback and the need for feedback in the students’ learning process?

What is the teachers’ concern about how students use, receive and interpret the feedback?

In which ways teachers cooperate with other colleagues in offering and giving feedback?

What are the evidences on the success of student’s learning?

How to use efficiently different feedback modalities as a starting point for design and decisions on future teaching and learning activities?

Purpose of the Study

In this research we aimed to investigate teacher’s opinions on the role and importance of immediate formative assessment and feedback in optimizing student learning. The purpose of the study was to define the opinions and beliefs regarding the formative assessment and feedback that teachers offers to the pupils in every learning activities from school.

For attending this goal, the research objectives were:

To present teachers’ opinion on different modalities for using feedback in the educational process.

To establish teachers’ concern and evidence about the ways in which the feedback influences the students’ learning process.

To identify the influence of the feedback on stimulating students’ learning process in the following educational activities.

To settle up some directions for improving teacher training on formative assessment and feedback.

Research Methods

As research method, we used a survey based on 20 items questionnaire. The items were developed from the feedback issues identified by John Hattie in the educational process (2014, 235-279). Each dimension mentioned by the author was divided in several questions (2,3,4,5 questions for each dimension presented above in this paper).

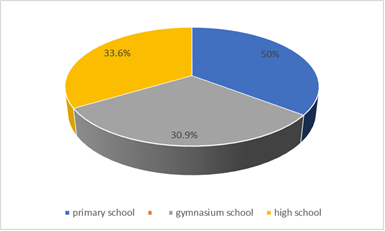

The sample of the research was comprised by 110 teachers from pre-university education institutions from Timișoara, with age between 28-60 years. 8 teachers (7.27%) were debutants, 28 teachers (25.45%) were complete teachers, 47 teachers (42.73%) with didactic degree II and 27 teachers (24.55%) with didactic degree I. Also, 39 teachers (35.45%) were teachers in primary education level, 34 teachers (30.91%) in gymnasium education level and 37 teachers (33.64%) in high school education level (Figure

The research was an ascertaining one, the obtained results being possible to use for the elaboration of a developmental strategy in teachers training on feedback issues (Table

We used a survey based on 20 items questionnaire. The items were developed from the feedback issues identified by John Hattie in the educational process (2014, 235-279). Each dimension mentioned by the author was divided in several questions (2,3,4,5 questions for each dimension presented above in this paper).

Respondent’s opinions were recorded on a 6-step scale (1 = total disagreement, 2 = general disagreement, 3 = partial disagreement, 4 = partial agreement, 5 = general agreement, 6 = total agreement). The questionnaire was applied both in "pencil paper" (69,09% of respondents) and on-line (30,91% of respondents).

Findings

Considering the research questions, we grouped teachers’ opinions recorded through their answers to questionnaire’ items in the following dimensions:

The importance of the feedback and the need for feedback in the students’ learning process (Q1, Q3).

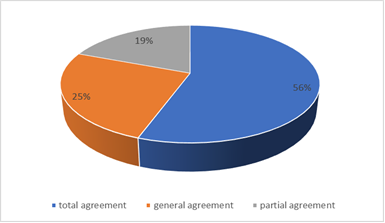

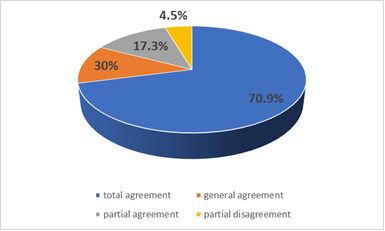

61 teachers declared total agreement on the importance of feedback in students’ learning process. 28 teachers declared a general agreement and 21 teachers declared partial agreement on this issue (Figure

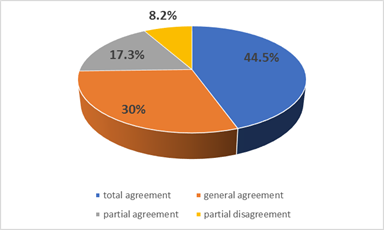

The responses regarding the need for offering an adequate feedback were having the following answers: 49 teachers-total agreement, 33 teachers-general agreement, 19-partial agreement and 9 teachers-partial disagreement (Figure

Using the praise as a feedback (Q2)

Although some of the teachers admitted that they do not exclusively use the praise as a feedback (4 teacher- partial disagreement). Many teachers (48 teachers - total agreement and 19 - general agreement) believe that the praise offered to their students is important, but is not overlapped with the information given as feedback. 39 teachers declared a partial agreement with this dimension of the feedback (Figure

Teachers’ concern about how students use, receive and interpret the feedback (Q4, Q5, Q6, Q7, Q8)

91 of the interviewed teachers totally agreed that they are concerned about how their students receive and interpret the feedback. 69 teachers claimed with total agreement that their students prefer the progress feedback and the most difficult tasks make students more receptive to their feedback. Also, 69 teachers responded (total agreement) that their students prefer feedback on progress rather than a corrective one.

Most of the teachers’ responses confirm that they teach to the students how to request, understand and use the received feedback (78 teachers with total agreement, 13 teachers with general agreement and 14 teachers with partial agreement). None of the teachers were totally disagreeing in this issue and only 5 of them declared partial disagreement on this request (Figure

Cooperation with other colleagues and feedback (Q9, Q10)

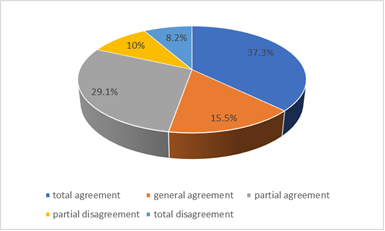

About cooperation with other teachers, 41 teachers totally agreed, 17 generally agreed, 32 partially agreed, 11 partially disagree and 9 totally disagreed with the necessity of accepting and offering feedback support in terms of finding the most effective methods to offer feedback to their students (Figure

Evidences on the success of student’s learning (Q11, Q12, Q13, Q14, Q15)

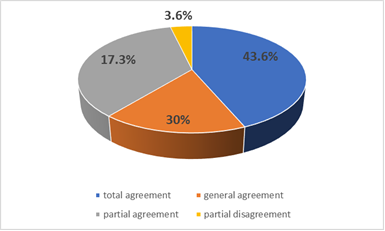

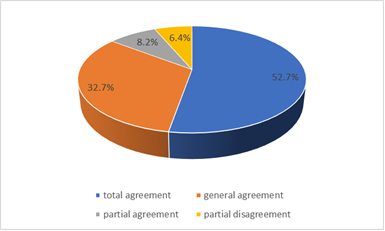

Many teachers said that their students can propose goals for an effective and sustainable learning and can adequately formulate the criteria of performance in their learning process. Thus, 58 teachers (52.7%) expressed their total agreement with this item (Q11) and 36 (32.7%) teachers expressed their general agreement. Only 9 teachers (8.2%) expressed partial agreement and 7 teachers (6.4%) mentioned partial disagreement with this issue (Figure

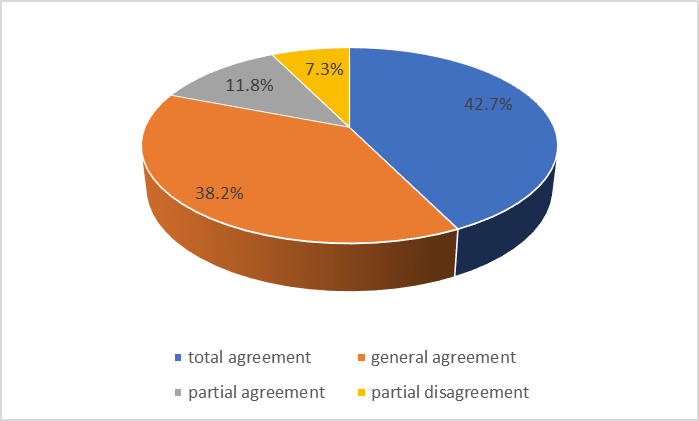

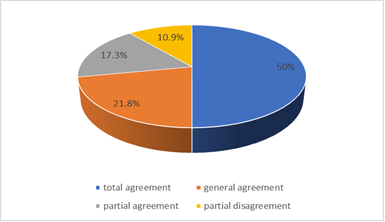

Regarding the responses to the Q12 item, 47 teachers (42.7%) sustained by their total agreement that their students meet the standards of the success and the success in learning and 42 teachers (38.2%) were have expressed their general agreement on this. Only 13 teachers (11.8%) declared their partial agreement regarding the fulfilment of the success and success standards in the educational activity of their students and 8 teachers (7.3%) their partial disagreement (Figure

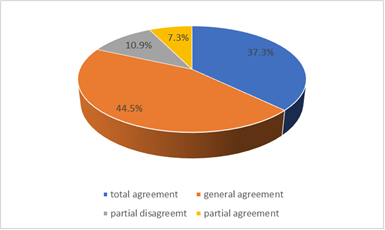

Teachers’ opinion on student challenges in the process of learning is mostly expressed in total agreement and general agreement (Q13). Thus, 41 teachers (37.3%) were in total agreement with the assertion of Q13 item, and 49 teachers (44.5%) expressed their general agreement regarding the standards of success, which are provocative for students. Only 12 teachers (10.9%) expressed their partial disagreement and 8 teachers (7.3%) expressed their partial agreement with this problem (Figure

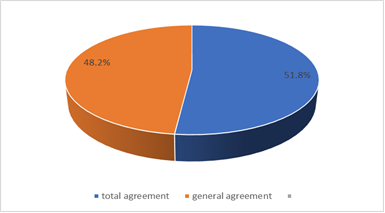

The respondents take account to the learning objectives, the criteria of performance and the standards that their students have established for their learning process and design the next lessons and teaching activities based on this information. Thus, 57 teachers (52%) expressed their total agreement with the assertion of Q14 item and 53 teachers (48%) responded with "general agreement" (Figure

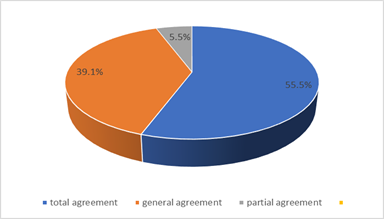

In terms of achieving the immediate formative evaluation on learning outcomes, teachers are using this type of assessment and considered its results as arguments for designing educational activities with an increased effectiveness. Thus, the answers to Q15 item are revealed the following: 61 teachers (55.5%) - total agreement, 43 teachers (39.1%) - general agreement and 6 teachers (5.5%) - partial agreement (Figure

Using the feedback as a start point for design and decisions on future teaching and learning activities (Q16, Q18)

79 of teachers (55-total agreement and 24 general agreement) affirmed that feedback has a prospective role and should be an input for future educational activities. 19 of the teachers were choose ’’partial agreement’’ and 12 of teachers responded’’ partial disagreement’’ with this feedback’ dimension (Figure

Opportunities for immediate formative assessment and considering it as a driver of optimizing learning (Q17, Q19, Q20)

Even if the frequency of discussions about formative assessment is a real one, its valences and virtues often do not lead to its practical use (due to the lack of time, convenience or insufficient understanding of its value). 75 teachers declared that they are concerned about creating opportunities for immediate formative assessment. 59 of the investigated teachers declared „totally agreement’’ and 16 „general agreement’’ this issue. Only 9 of the teachers declared „partial disagreement’’.

From the teachers’ answers we note that 79 of them declared that they use all the time (totally agreement) different methods and modalities for carrying out a learning centred teaching.

Teachers affirmed that in their teaching activity they emphasize all the time the learning done by the students and that they use teaching as a way of fostering and optimizing learning in a rate of 80%. 22 of teachers partially agreed that teaching is a way of optimising the students’ learning.

Conclusion

Concluding on the obtained results, we could point that:

Teachers recognize the role and importance of the immediate formative assessment and feedback in optimizing the following learning activities;

There is a concern for teachers for use immediate formative evaluation and feedback as "ingredients" that sustain the learning process’ optimization;

Declaratively, teachers focus their teaching activity on stimulating an effective learning process;

Teachers believe that using different modalities for a formative and immediate assessment will optimize students’ learning that becomes (more) efficient and (more) sustainable.

Despite this previously mentioned concern, teacher should improve some specific dimensions of the feedback in their teaching activity.

The answers of the questioned teachers show us that they often use praise as a modality to motivate students to learn. But, many teachers have the opinion that offering praising to students who achieve learning performance is equivalent to give them feedback. They do not distinguish with sufficient precision between praise and feedback. The praise as a feedback could be used as a support for reducing students’ problematic behaviour or may serve as an important factor to establish predictable and positive classroom contexts (Partin, Robertson, Maggin, Oliver, & Wehby, 2009). So, it could be an instrument for assuring student satisfaction regarding the task of assessment. It is demonstrated that satisfied students receive more general praise, general ability feedback, effort feedback and less negative teacher feedback (Burnett, 2002).

Providing feedback to students means more than praising them when it is appropriate. An efficient feedback involves also teachers’ comments on students’ performance or when their answers are inaccurate, insufficient or even wrong. This fact is not being considered as a limit of the teaching or of the learning process, a cognitive deficit or focalization on the negative aspects. On the contrary, the recognition of the mistake offers many opportunities (Hattie, 2014). Students’ mistake is considered an opportunity for the teachers to provide a relevant and meaningful feedback. For the students it is an opportunity to learn, to become aware of their learning problems and to progress in acquiring the new knowledge.

The questionnaire data showed that teachers’ feedback should be sustained by specific evidence of its efficiency in optimizing students’ learning. These testimonials come from students’ responses to the given feedback, from their improvement of motivation to learn, from the obtained learning performance (progress feedback) or from other colleagues’ expertise on formative assessment and feedback. This is about how students understood the received feedback (Gamlem & Smith, 2013; Poulos & Mahony, 2008) and how teachers reflect on the teaching activity together with their colleagues (Bell, 2011). Using guidance and feedback for the students’ activity as a loop and continuous assessment modalities we assure the basis for enhancing also the quality of teachers’ activity. The guidance offered through the feedback process is a modality that could be used in the educational process as a valuable diagnostic tool to help teachers to identify more precisely the strengths and the weaknesses of the process and the efforts for remedying shortcomings (Hounsell, McCune, Hounsell, & Litjens, 2008). For avoiding the situations in which some teachers don’t see the impact of the feedback, they should discuss feedback with their students and encourage them to use the received feedback for improving the process of learning (Haigh & Dixon, 2007). Students’ feedback on the received feedback, reflection and feedback through peer teaching are modalities which could be continuously improved through training sessions or development strategies in teacher training.

The questioned teachers affirmed that a good feedback practice is imperiously related to student’s learning process and should be settled on specific guidelines which help teachers to optimise and to do more efficient their future teaching. It is about creating opportunities for giving a good feedback in the teaching process (an immediate formative assessment) and for reconsidering the following teaching activities through the received students’ feedback (Brinko, 1993; Seldin, 1997).

Despite of the opinion that many teachers consider their role and mission only to teach, the educational process is a teaching-learning-evaluating process. Therefore, the goal of the teachers’ feedback is to facilitate students’ learning. The effectiveness and efficiency of teachers’ activity are determined by the students that have been able to learn (more) quickly and (durably) in the given context. In this respect, the need for developing teachers’ feedback skills is related to the imperious need for an effective learning process. Teachers should know the conditions under which assessment supports the learning process. This will be the framework for teachers to review the effectiveness of the assessment process (Gibbs & Simpson, 2005). It is about to identify, promote and disseminate opportunities and best practices for evaluation process focused on students’ learning (Carless, Joughin, & Mok, 2006) or being prepared to use learning oriented assessment in everyday activities (Carless, 2007; Keppell & Carless, 2006).

In the present educational process, many teachers still have some difficulties in using an effective assessment strategy. This is an important professional dimension which should to be improved in teachers’ feedback skills through applying principles of good feedback practice that (Nicol & Macfarlane-Dick, 2006): helps clarify what good performance is (goals, criteria, expected standards); facilitates the development of self-assessment (reflection) in learning; delivers high-quality information to students about their learning; encourages teacher and peer dialogue around learning; encourages positive motivational beliefs and self-esteem; provides opportunities to reduce the gap between current and desired performance and provide information to the teachers that can be used to help shaping an efficient teaching process.

In conclusion, teachers training on the formative assessment and feedback could be developed on the following directions:

Understanding of the difference between the formative evaluation process and an effective formative assessment and feedback.

Modalities to identify the difficulties and specific issues of the students’ learning.

Using different types of formative assessment and feedback (face to face feedback, written feedback, on line feedback).

Strategies for delivery of an efficient formative assessment and feedback, adapted to the specific educational context (differentiated and individualised assessment and feedback): methods, instruments and ways of organising the evaluation process.

Development of a holistic approach on the evaluation process, which is constructed on the specific scientific evidence and teachers’ good practices.

References

- Bell, M. (2001). Supported reflective practice: a programme of peer observation and feedback for academic teaching development. International Journal for Academic Development, 6(1), 29-39.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: principles, policy & practice, 5(1), 7-74.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability (formerly: Journal of Personnel Evaluation in Education), 21(1), 5.

- Brinko, K. T. (1993). The practice of giving feedback to improve teaching: What is effective? The Journal of Higher Education, 64(5), 574-593.

- Burgess, A., & Mellis, C. (2015). Feedback and assessment for clinical placements: achieving the right balance. Advances in medical education and practice, 6, 373.

- Burnett, P. C. (2002). Teacher praise and feedback and students' perceptions of the classroom environment. Educational psychology, 22(1), 5-16.

- Carless, D. (2007). Learning‐oriented assessment: conceptual bases and practical implications. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 44(1), 57-66.

- Carless, D., Joughin, G., & Mok, M. (2006). Learning-oriented assessment: principles and practice. Assessment and evaluation in Higher Education, 31(4), 395-398.

- Dunning, D. (2005). Self-insight: Roadblocks and detours on the path to knowing thyself. New York: Psychology Press.

- Gamlem, S. M., & Smith, K. (2013). Student perceptions of classroom feedback. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 20(2), 150-169.

- Gibbs, G., & Simpson, C. (2005). Conditions under which assessment supports students’ learning. Learning and teaching in higher education, (1), 3-31.

- Haigh, M., & Dixon, H. (2007). ‘Why am I doing these things? engaging in classroom‐based inquiry around formative assessment. Journal of In‐Service Education, 33(3), 359-376.

- Hattie, J. (2014). Visible learning. Guide for teachers. Bucharest: Trei Publishers.

- Hattie, J. (2016). Know thy impact. On Formative Assessment: Readings from Educational Leadership (EL Essentials), 36.

- Hounsell, D., McCune, V., Hounsell, J., & Litjens, J. (2008). The quality of guidance and feedback to students. Higher Education Research & Development, 27(1), 55-67.

- Ion, G., Barrera-Corominas, A., & Tomàs-Folch, M. (2016). Written peer-feedback to enhance students’ current and future learning. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 13(1), 15.

- Ion, G., Cano-García, E., & Fernández-Ferrer, M. (2017). Enhancing self-regulated learning through using written feedback in higher education. International Journal of Educational Research, 85, 1-10.

- Keppell, M., & Carless, D. (2006). Learning‐oriented assessment: a technology‐based case study. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 13(2), 179-191.

- Lee, I., Mak, P., & Burns, A. (2016). EFL teachers’ attempts at feedback innovation in the writing classroom. Language teaching research, 20(2), 248-269.

- Leibold, N., & Schwarz, L. M. (2015). The Art of Giving Online Feedback. Journal of Effective Teaching, 15(1), 34-46.

- Nicol, D. J., & Macfarlane‐Dick, D. (2006). Formative assessment and self‐regulated learning: A model and seven principles of good feedback practice. Studies in higher education, 31(2), 199-218.

- Partin, T. C. M., Robertson, R. E., Maggin, D. M., Oliver, R. M., & Wehby, J. H. (2009). Using teacher praise and opportunities to respond to promote appropriate student behavior. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 54(3), 172-178.

- Poulos, A., & Mahony, M. J. (2008). Effectiveness of feedback: The students’ perspective. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(2), 143-154.

- Richards, K., Bell, T., & Dwyer, A. (2017). Training Sessional Academic Staff to Provide Quality Feedback on University Students' Assessment: Lessons From a Faculty of Law Learning and Teaching Project. The Journal of Continuing Higher Education, 65(1), 25-34.

- Sadler, D. R. (1998). Formative assessment: Revisiting the territory. Assessment in education: principles, policy & practice, 5(1), 77-84.

- Sadler, D. R. (2010). Beyond feedback: Developing student capability in complex appraisal. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(5), 535-550.

- Sargeant, J., & Mann, K. (2017). Feedback in medical education: Skills for improving learner performance. ABC of Learning and Teaching in Medicine, 2, 29-32.

- Seldin, P. (1997). Using student feedback to improve teaching. To improve the academy, 16(1), 335-345.

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of educational research, 78(1), 153-189.

- Wenrich, M. D., Jackson, M. B., Maestas, R. R., Wolfhagen, I. H., & Scherpbier, A. J. (2015). From cheerleader to coach: the developmental progression of bedside teachers in giving feedback to early learners. Academic Medicine, 90(11), 91-97.

- Wiliam, D. (2011). Embedded formative assessment. Solution Tree Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Bersan, O. S., Țîru, C. M., & Dumitru, I. A. (2019). Formative Assessment And Feedback – “Ingredients” For An Effective And Durable Learning. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 448-462). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.54