Abstract

The article sets out to investigate to what extent do teachers apply, and initiate practices discovered at teacher seminars and how these can be linked to the field of neuroscience and didactics. Moreover, I will make use of the term “Neurodidaktik” (En. neurodidactics), as it refers to how learning processes and learning difficulties (in this case learning German as a foreign language) can be interpreted and understood through current findings in neuroscience. Starting from a practical framework (the classroom), the article attempts to fill in a gap on a topic seldom talked about: didactic materials presented at workshops for teachers and their usefulness. Moreover, what motivates their usage? The first part of the paper examines the need for neurodidactics and its definitions. The second part explores some principles of neurodidactics that can be applied in classroom and examples of relevant classroom activities. The third part brings the findings of a questionnaire applied to teachers of German foreign language who participated in teacher seminars organized by the Goethe-Institute Bucharest and its partner institutions. Focusing on the use of certain materials (presented in seminars and their usefulness in percentages), the questionnaire examines which principles of neurodidactics are applied in class and some corresponding activities offered as examples in teacher seminars and trainings. The working hypothesis starts from the idea that teachers are motivated to use brain-stimulating exercises in order to create and impact the classroom atmosphere and less for their learning content.

Keywords: NeurodidacticsGerman as a foreign languageteacher trainingdidactic material

Introduction

A link between learning and the brain is inextricable. It took humanity quite a few years to explore the brain from a different perspective than from a mere material and structural one. In other words, the exploration of the outside of the brain, with all its physical traits, has been replaced by an explosion of findings in the field of neuroscience. In her book

Neurodidactis For a definition

I define neurodidactics as a possible didactical method that makes usage of certain classroom activities, in order to stimulate neuronal connections and prepare the brain for learning. Neurodidactis finds its roots in neuroscience and the study of the brain in specific contexts: stress situations, image recognition, social interaction etc. Neurodidactics is based on the study of the brain in different life stages, in order to explain how and why learning changes throughout one’s life. This didactical method implies tasks, activities and exercises in class, but also finds its way in the conception of textbooks for all learners’ groups (the publishing house Hueber in Germany).

My proposed definition cannot be exhaustive, as it is not the case. Usually, with any teaching method there is no absolute functional and perfect one. Neurodidactics implies a mix of methods, resorting to student-centred approaches, while sufficiently documenting and including the brain in organizing classroom activities. The learner stops being a neutral container of information and shifts towards the centre of learning context. Neurodidactics implies the creation of this context, turning the classroom into a learning landscape, in which individuality finds the right place

Neurodidactics and its Gains for Foreign Language Teaching

The first reaction a teacher of German gets from learners/beginners is that German is just too difficult. It sounds unfair to most of us, but it has a real substratum. Language is a complex system and how we acquire, for e.g. our first language, still puzzles scientists. It has also become clear that the learner nowadays has subtly changed: from digital natives to fast-on-track millennials, learning (a foreign language) has become a life skill. Going back to the early stages of a human life (childhood), one can easily discover how effortless children learn to speak their language. It is also clear that the stages of developing speaking a language are identical in all languages on our planet (Frederici, 2011). In the case of learning a new language, stages run similarly, children turn out to be linguistic geniuses, navigating through languages and switching effortless. But after a certain age (4-7) there will be a dominant language, the scaffold for learning systematically other languages.

Teaching adults and young adults a foreign language is based, in modern approaches for teaching languages, on the Common European Framework for Languages. This level standardization has been useful, but unfortunately the CEFL is twenty years old. There have been several attempts to adjust certain level descriptions, but efforts are made in dealing with the four to five competences: reading, writing, listening/listening-seeing and speaking. Each competence has also other categories/contexts: speaking – spoken interaction and monolog, listening – listening and seeing. The existence of the levels and competences has also helped modern approaches to teaching foreign languages reconsider how we actually teach and train these skills. One relevant conclusion would be that these competences do not emerge in isolated modes and that, at some point during the learning stages, differences between the productive and receptive part can grow. The key question in the discussion at hand resides in how a learning context can be created, in order for all four to five competences to be trained. This is somehow different to classical teaching methods that have also influenced foreign language teaching: behaviourism, constructivism and the grammar-translation method. Firstly, having a framework with levels, each student is picked up at his or her level and can progress. Secondly, creating a context means that there will be a lot of authentic linguistic input and thirdly, the teacher becomes a guide to efficient learning, convincing his/her pupils to take the language and learning strategies outside the classroom.

Neurodidactics in class: activities, tasks, examples

Before giving some examples of classroom tasks and activities designed to prepare the brain for learning, I will provide a small detour and reveal the current teacher training programmes of the Goethe-Institute München in collaboration with several German universities. The Goethe-Institute is the main provider for German courses and teacher training programmes worldwide. It has also reformed the teacher training materials in the past six years, adjusting the principles of teaching from competence-focused to the multi-layered perspective on teaching. The series Deutsch Lehren Lernen (Learning to Teach German) focuses more on intersections between creating the proper learning context to what sets German from other languages apart. Moreover, the series explores, for e.g. the importance of social forms, project-based learning and new media. Competences are all integrated in the provided examples for activities and work-sheets. After the implementation of the new programme, the Goethe-Institute Bucharest has created a national network of teacher trainers in Romania and my research is based on the findings from teacher seminars I provided and their connection to neurodidactics.

In her book

Neurotransmitters are divided into inhibiting or stimulating, but many neurotransmitters, through their concentration, can show both features […] The biochemical interplay can deeply influence fear and stress, but also prompt a happy and stress resistant disposition. Memory, concentration and creativity depend on neurotransmitters. (Grein, 2013, p. 23).

The author explains how memory, concentration and creativity depend on the release of neurotransmitters, as she points out that each learner learns differently, hence needs an individual neurotransmitter-cocktail to be in balance. Grein discusses Acetylcholine and its positive effect on concentration (in the right amount), Noradrenalin (a stimulant and how, if in the right amount, it can increase motivation), Dopamine (a stimulant that influences concentration, curiosity and motivation), GABA (

To further elaborate on what creating a learning context means, I will start with detailing the central relationships that are active in a classroom: teacher – learning possibilities (social forms, learning materials, media, tasks etc.) – learner. Schart and Legutke (2012, p. 65) explore in

The list below provides two examples of classroom activities linked to how I understand neurodidactics can improve the learning context. I will give the example in German and provide a short description in English.

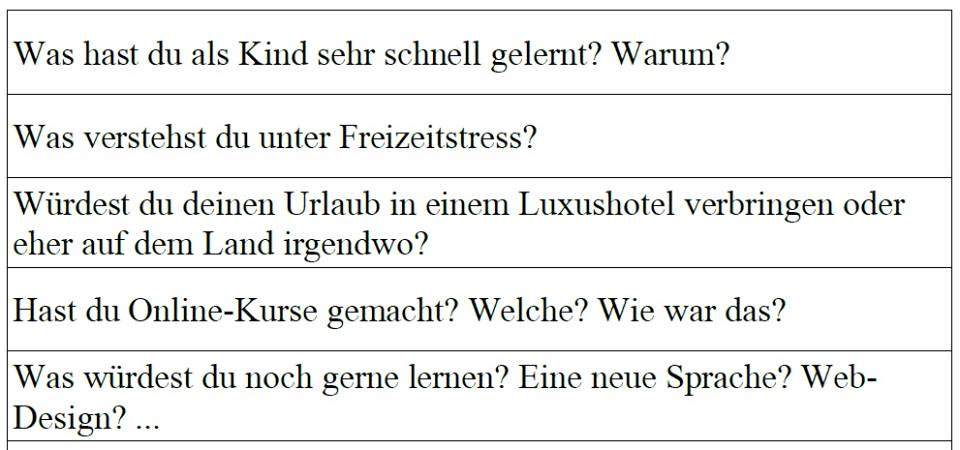

Preparing the brain for learning: Klassenspaziergang (classroom walk, fig. 1) for levels A1-C2. The teacher provides a set of questions (8-12), on paper strips. The latter are hanged, at a certain distance from each other, on the classroom walls. Students walk with a partner to each question and discuss it. The questions can be related to the class topic or not. Positive effects: students acknowledge that they are in the German class, make use of the language and interact.

Activities of cooperative learning: KooperativesLesen/ Hören (cooperative reading and listening) for levels A1-C2. Texts or audios can be long, boring and sometimes difficult. Divide the class into groups of 4 or pair the students. Each student receives a different part of the text or has to focus on listening to a certain part of the track, with different tasks (either to select certain information or to answer questions). At the end of the sequence the groups and pairs work together and inform each other. Positive effects: students make use of the language and interact. During cooperation with another peer making mistakes becomes irrelevant.

Problem Statement

Research has not yet focused on what motivates the selection of teaching materials provided in seminars for teachers. Moreover, if there is no follow-up after the seminar, the percentage of materials delivered in the training sessions that are actually applied in class remains unknown. Through a questionnaire I attempted to discover what drives and determines the usage of activities, exercises and tasks explored in the teacher training sessions. The main reason for such an endeavour aims at improving the quality of the seminar, but also to explore the link between neurodidactics and the delivered materials during the training sessions. The questionnaire was applied over a period of three months, March to June 2018 and sent to thirty teachers of German as a foreign language.

Bridging the gap between theory and practice

As I described in section

Research Questions

The main research question aims at exploring the reasons teachers select certain materials provided in trainings. Do they choose materials based on their content (for e.g. grammar focused) or they prefer materials that stimulate interaction and help create a positive learning atmosphere? Does the actual experimentation with the teaching materials during the training session influence their decision? Before describing the purpose of the study, there are two relevant aspects I would like to discuss: content-based materials and the usage of adapted ones (for stimulating interaction in classroom). Textbooks usually include all language phenomena and cultural elements the learner needs to acquire in order to be proficient in a certain language. But textbooks are only a part of the learning material and all teachers include supplementary and adapted materials to achieve the learning goals set by the curricula or the learners’ own personal targets.

Materials based on content in teaching German as a foreign language

Didactic materials in teaching German as a foreign language include textbooks/workbooks and supplementary teaching and learning materials. Moreover, I see textbooks as media in the teaching and learning process. Rösler and Würfeldefine media in teaching as instruments through which content, exercises, tasks etc. are conveyed, facilitating the acquiring of knowledge and competences (Rösler & Würfeldefine 2012, p. 12). This also means that at the basis of teaching materials (including textbooks) we find authentic texts (for training reading, seeing/listening and adjacent competences) adapted to a proper language level. Content based materials refer to supplementary teaching materials and have a precise focus: for example, worksheets that train the relative pronoun in German. Usually content-based materials are linked to certain language phenomena (from grammar, vocabulary to pronunciation) and are used to train or fill in knowledge gaps on a particular topic.

Adapted materials focused on interaction and cooperation.

The supplementary adapted materials intended to stimulate interaction can also centre on particular topics, but as a general learning goal they are meant to prepare the brain for learning and support cooperative activities in the classroom. Adapted materials that focus on student interaction and cooperative learning can be used at the beginning of a lesson (as a warm-up), in the middle (to support the understanding of texts) and at the end of a sequence.

Classroom walk (as described in section

1 .3)Cooperative reading and listening (as described in section

1 .3)Partner interview (Partner A and Partner B have different questions on certain topics, for example housing or living in the city)

The Hot Seat: a fun way to revise vocabulary from the previous lesson and a good warmer): Divide the class into two teams. Place a seat in front of the board. A learner sitting with the back to the board will have to guess the word the teacher writes on it, by listening to the definitions offered by the team.

The list provided above is incomplete, but is relevant for the purpose of study, as these are some examples provided in teacher training seminars to illustrate interaction and cooperation.

Purpose of the Study

This paper will describe what materials linked to neurodidactics are known to teachers, what are the most used materials provided in teacher seminars and based on what the selection is made by teachers. My endeavour starts with the interpretation of a questionnaire applied to teachers of German as a foreign language, who attended at least one teacher training session in the past year. The questionnaire explores what motivates their participation, how many teaching materials (in percentages) were useful and what motivates usage in class. The questionnaire included an open question where teachers were able to suggest other high impact activities they do and explain why they think these are successful.

Research Methods

The main research method used is the survey. Having a descriptive purpose the questionnaire collected data on personal background (from teaching experience to the number of attended seminars in the past two years), factors that influence participation to a teacher training session, preferred teaching materials (designed for a certain level, grammar focused etc.) and on the impact, on a scale from 1 (very good) to 5 (poor), certain activities presented in seminars had in classroom.

Findings

After analysing the provided set of answers the survey showed that all teachers attended at least 2 seminars in the past two years. Moreover, 90% of answers had as top selection criteria for attendance: topic, materials provided and trainer. One of the answers gave additional criteria of choice: certificate of attendance and prior knowledge on the topic. A section of the survey, which had an informative purpose and will be subject to further investigation, aimed at revealing what steps teachers undertake in creating a learning context.

Materials delivered in teacher training sessions

The percentage of didactic materials provided in teacher training sessions varied between a low of 20% to a high of 70%. In the section of the survey in which the teachers where asked to evaluate the impact the proposed activity, task or exercise had in the classroom the highest scores were given to activities that stimulate interaction, like the hot seat or the classroom walk, and the materials based on cooperation were also evaluated positively. The teachers’ own proposals for activities that have a positive impact on classroom were project-based learning, portfolios and classroom learning stations.

Criteria for selecting materials

The section of the survey focused on nine criteria for selecting teaching materials received during teacher training sessions and demanded yes and no answers. Extracted from the questionnaire, the section included the following: During a teacher training session I prefer to receive didactic material that:

Can be used directly and does not require adaptation.

Has been designed for a certain language level.

Trains grammar.

Focuses on interaction between students.

That helps students communicate (speaking or writing).

I have experimented with.

Others have experimented with.

The trainer recommends.

Can be used during an entire lesson (similar to a ready-made lesson).

All respondents of the survey have chosen materials that focus on interaction and help students communicate (speaking and writing). Two respondents pointed to the criteria that do not influence their choice for implementing the delivered teaching materials are the ones designed for a certain language level, train grammar and that can be used during an entire lesson. The designed activities during the teacher training seminars take into consideration the following aspects (corresponding to the criteria above): didactic materials are experimented by participants and during the training session there are sequences, in which teachers can share their experience with certain activities they use in class. Secondly, all delivered materials can be adapted to a certain language level or an age group. Moreover, most didactic materials focus on production, activation and cooperation. The last section of the survey investigated, which tasks, activities and proposed exercises have been successful in class.

Conclusion

The last part of the survey investigated which tasks and activities were useful on a scale from 1 to 5. The answers also included a column with the title “not used”. The end of the survey offered respondents the possibility to enter their own suggestions for useful activities and explain why they think these can have a positive outcome on the class. The list included a majority of didactic materials offered during training sessions. In order to better describe the results, I grouped the activities into two categories: (brain) activating exercises and warm-ups, cooperative learning and communicative tasks (stimulating spoken interaction).

Brain activating exercises and warm-ups. Preparing the brain for learning.

Brain activating exercises and warm-ups play a decisive role in the sequences of any lesson. They are beneficial, because they allow a playful and subtle crossing into another learning sequence. Moreover, when placed at the beginning of a lesson, they signalize to students that the German class has started and that they are required to make use of the language and interact. From the list provided to teachers, there were some activities that implied movement inside the classroom (see section

Cooperative learning activities.

In the teacher training session there were examples of how texts or audio texts can be used to improve cooperation in a group. Not having to read entire texts, but given different approaches to the text, students in a group could focus on extracting, for example, information on a certain topic during reading, while others can identify unknown words or difficult ones. At the end of the reading time, students haveto discuss their results. This sort of activity scored either a 1 or a 3.

From the answers provided through the survey, there are several conclusions that can be drawn from it.

Teachers prefer to select activities that impact the atmosphere in class and help students communicate.

Teachers prefer didactical materials that can be adapted.

Teachers prefer to experiment with the didactic materials during a training session.

Teacher also can make use of activities that require movement in class.

Teachers have mentioned other tasks they use in class and argued for their utility, underlining that most of them spark curiosity and interest among students and not necessary train a certain language phenomena.

At the basis of selecting teaching materials from training sessions we find not necessarily the need for improvement certain competences in students (topic-based, vocabulary, pronunciation, grammar etc.), but rather a need for materials that engage and activate students, enabling cooperation and communication. Moreover, teachers make use of supplementary didactic materials, in order to integrate all language skills during class: reading, writing, listening-seeing and speaking. This also showcases that a “mix of methods “and different media are required to train these skills. Activities that actually prepare the brain for learning and stimulate cooperation also improve the overall learning context. And this is also a reason why teachers opt for the transition of such didactical materials from the training room into their own classroom.

References

- Bizuleanu, D. (2016). Selbsteinschätzung der Lerner durch transparente Lernziele [Students‘ Self-Assesment and Transparent Learning Goals]. In C. Teglas, R. Mihele&V. Mezei (Eds.).DinamicaLimbajelor der Specialitate. Tehniciși strategii inovatoare [The Dynamics of Languages for Specific Purposes.Innovations and Strategies].(1st ed., pp. 185-196). Cluj-Napoca: Casa Cărții de Știință

- Friederici, A.D. (2011). Den Bär schubst der Tiger. WieSpracheimGehrinentsteht [The Tiger pushed by the Bear. How Language Appears in the Brain]. In T. Bonhoeffer&P. Gruss (Eds.). Zukunft Gehrin. Neue Erkenntnisse, neue Herausforderungen. Ein Report der Max-Planck-Gesellschaft [Brain Future. New Findings, New Challenges. A reprot from the Max Planck Research Institute]. (1st ed., pp. 106-121). München: C.H Beck

- Grein, M. (2013). Neurodidaktik. Grundlagen für Sprachlehrende [Neurodidactics. Basics for Foreign Language Teachers].Ismaning: Hueber

- Rösler, D.&Würfel, N. (2014). Deutsch Lehren Lernen 5. Lenrmaterialien und Medien [Learning to Teach German 5.Didactic Materials and Media].München: Klett-Langenscheidt

- Schart, M.&Legutke, M. (2012). Deutsch Lehren Lernen 1. Lehrkompetenz und Unterrichtsgestaltung [Learning to Teach German 1. Teaching Competence and Instruction Design]. Berlin: Langenscheidt.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Conkan, D. (2019). Neurodidactics: The Selection Of Teaching Materials For German As A Foreign Language. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 409-418). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.50