Abstract

Midwifery education aims to develop successfully confident and competent midwives with strong prenatal self-efficacy (PNSE) in the clinical learning environment (CLE), regarding the preceptor-preceptee academic relationship (CTCI). The meaning of preceptorships is being together in the clinical field in "real time", doing together, and getting along together. In the current study, within this context, the assumption is that matched learning styles of the preceptee's and the preceptors' may facilitate the preceptorship relationship as well as developing the preceptees' prenatal self-efficacy. Because the preceptor’s function as role models, they are able to promote their preceptees' professional attitudes, knowledge and skills. This learning and professionalism process is gained by closing the gap between theory and clinical practice, enhance self-confidence and the probability to deliver quality care. Based on the literature, a theoretical model was constructed aiming to in order to examine among midwifery students the impact of a matched preceptor-preceptee learning styles in order to find a connection between the quality of preceptorship relations and student self-efficacy. The model was based on discussions and dialogues, which may generate a social framework, leading midwifery students to socialization into the midwifery profession.

Keywords: Midwifery educationpreceptorshiprole modeltraining and qualificationprenatal self-efficacysocial construction

Introduction

The midwife is a crucial assistant in labour (Feldhusen, 2000). The profession has been recognized worldwide for reducing infant morbidity and mortality (Bharj et al., 2016) and facilitating safe delivery (Phillips & Hayes, 2006). The global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016–2020 (WHO, 2018) outlined four critical objectives in order to develop nursing and midwifery. Two of them are relevant to the present study: (a) "Ensuring an educated, competent and motivated nursing and midwifery workforce within effective and responsive health systems at all levels and in different settings"; (b) "Working together to maximize the capacities and potentials of nurses and midwives through intra and interprofessional collaborative partnerships, education and continuing professional development". These two objectives are inherent components of the preceptorship model, which aims to create and promote professional competency. The preceptorship model is defined as the relationship (based mainly on conversations and discussions) between a preceptor (one or two) and a preceptee for a bounded period (Lambert & Glacken, 2006; Myric, 2002; Myric & Young, 2004; Phillips, Fawns, & Hayes 2002).

The midwife is a crucial assistant in labour (Feldhusen, 2000). In Romania, for example, mortality rates are 8.8 per 100,000, as compared to the EU average of 3.8 for infants, and 13.0 as compared to 4.9 for mothers (Vladescu, Scintee, Olsavsky, Hernandez-Quevedo, & Sagan, 2016). Therefore, worldwide the profession has been recognized as important for reducing infant morbidity and mortality (Bharj et al., 2016) and facilitating safe delivery (Phillips & Hayes, 2006). The global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016–2020 (WHO, 2018) outlined four critical objectives in order to develop nursing and midwifery. Two of them are relevant to the present study: "Ensuring an educated, competent and motivated nursing and midwifery workforce within effective and responsive health systems at all levels and in different settings", "Working together to maximize the capacities and potentials of nurses and midwives through intra and interprofessional collaborative partnerships, education and continuing professional development", i.e., a preceptorship model. The aim of the preceptorship model is to create and promote professional competency. It is defined as the relationship between a preceptor (one or two) and a preceptee for a bounded period (Lambert & Glacken, 2006; Myric, 2002; Myric & Young, 2004; Phillips, Fawns, & Hayes 2002).

The art of preceptorship can de described by three characteristics: Being together – the preceptor and a preceptee are together in the clinical field near the patient and are learning in "real time" how to focus on the patient's needs and safety; Doing together – practice and perform relevant skills; Getting along together – balancing between the professional relationship of the preceptor-preceptee and patient centred care (Nielsen et al., 2017). The authentic experience of successfully completing a task can be the most influential source of self-efficacy, i.e., one's belief in his/her ability to perform a task (Bandura, 2006). Nurses with high levels of self-efficacy are able to continue performing well despite adversities such as failures, environmental obstacles and problematic situations in the relationship between the student-preceptee and the midwife-preceptor. In fact, nursing research has shown links between self-efficacy and competence (Lauder et al., 2008).

Students with high prenatal self-efficacy become more confident and competent midwives. One of the primary factors which contribute to successful development of self-efficacy in midwifery education is the clinical learning environment, particularly the preceptor-preceptee academic relationship. Matched preceptee and preceptor learning styles may contribute to their relationship on the one hand, and preceptee' self-efficacy on the other. However, this hypothesis has not yet been tested.

The literature review was conducted in order to answer the question: According to the professional literature in midwifery education, what theoretical constructs and relationships among them are necessary to examine the impact of matched preceptorship relations on midwifery students' self-efficacy?

Main Body

In the following sections, a brief summary of the theoretical literature review regarding the three main concepts: PNSE (prenatal self-efficacy), CTCI (preceptees’ perception of the preceptors' qualities as role models) and VARK (adult learning and learning styles) will be presented.

PNSE – Prenatal Self-Efficacy Theory.

The sense of personal efficacy concerns one's belief in having capabilities and abilities to affect his/her life. In addition, self-efficacy is a belief in one's competence in organizing and accomplishing behaviours to further one's goals (Bandura, 1978).

Self-efficacy includes solving difficult situations, performing new tasks and dealing with difficult situations. Possessing self-efficacy makes a difference in one’s confidence, and how one feels, thinks, and behaves (MacLaughlin, Moutray, & Moldoon, 2008). In addition, self-efficacy increases one's sense of self-control and contributes to effective performance (Bandura & Locke, 2003; Murphy & Kraft, 1993; Zulkosky, 2009). In nursing practice-based education, new knowledge and skills are provided to students-preceptees who are instructed and guided by the nurse-preceptor. Accordingly, in the study of midwifery, self-efficacy was found to predict the energy and persistence of a students’ drive to deliver quality care (Jordan & Farely, 2008).

CTCI – Preceptees’ Perception of the Preceptors' Qualities as a Role Model.

Preceptors who function as role models facilitate the development of their students' professional attitudes, the commitment to fill the gap between theory and clinical practice, and the developing and nurturing self-confidence and self-efficacy (Karimi, Dabbaghi, Oskouie, & Vehviläinen-Julkunen, 2009). Studies have shown that the attributes of the preceptor are among the most influential factors in the clinical learning environment affecting student learning and self-esteem (Gray & Smith, 2000), and the development of confidence in students’ skills (a characteristic of self-efficacy) (Miles, 2008). In addition, preceptors are the primary link in the process of transitioning curricular theory into clinical practice (Carlson, Wann-Hansson & Pilhammar, 2009) by helping students cope and learn from difficulties they encounter in the clinical field and advance continuous clinical learning (Duffy, 2009).

Social construction theory asks us to rethink virtually everything that we have thought and have been taught about the world and us. In other words, the world exists for us to explore new forms of action. The way we observe the world will help us "to save forests, build strong buildings and improve the health of children" (Gergen, 2008, pp. 9). The main point in understanding social construction theory is to know how to speak together, listen to new voices, have the courage to ask questions and think about symbols". According to Gergen (2008, pp. 12) "The future is ours. Together we will create a new reality". The sociological and psychological background of midwifery and distribution of its professional knowledge occurs in various practice settings, such as teams of nurses and/or midwives (Phillips & Hayes, 2006).

Berger and Luckmann (1966) discuss the "Social Construction of Reality" in terms of a dialectical process between "externalization", "objectivation", and "internalization". They claim that "the objectivated social world is reprojected into consciousness in the course of socialization” (ibid. pp. 78-79) and that knowledge “is at the heart of the fundamental dialectic of society “(ibid. pp. 84). Later they posit: “Secondary socialization is the internalization of institutional or institution-based 'sub-worlds” (ibid. pp. 158). Clearly nursing education is one aspect of such a sub-world, and the knowledge midwifery preceptors provide their preceptees helps them construct a social as well as a medical reality. In other words, this sub-world incorporates ongoing guidance involving situations encountered by the preceptor when accompanying the preceptee, including role modelling of skills whiles providing feedback and support (Goldman & Cojocaru, 2017). The preceptor-preceptee relationship is conducted mainly via communication, i.e., conversations and dialogues that provide vast support as well as prompting professional learning needs. Conversations are fundamental for students' induction and socialization into the profession (Phillips, 2002).

From a sociological perspective, the conversations, dialogues and discussions, in which the student-preceptees are engaged with their midwife-preceptors (as well as additional allied healthcare providers), are a public form of reflective practice (Phillips & Hayes, 2006). Implicit in these conversations is the perceived positioning students adopt in relation to themselves and to the preceptor as a professional role model. Phillips and Hayes (2006) state, that the "positioning theory has a place in midwifery education as it facilitates the understanding of meanings and themes that emerge from the important moment-to-moment interactions that occur in practice settings" (p. 226).

In addition, according to Positioning Theory, a

Role theory, in sociology, concerns one of the most important features of social life, characteristic behavior patterns or roles (Biddle, 1979, 1986). It relates to theatre metaphors and terms such as actors and roles (Goffman, 1959). According to Biddle (1986) at least five perspectives may be discriminated in research within the field: functionalists, symbolic interactionists, structuralists, organizational role theory which represents other perspectives of role theory, and cognitive role theory. Two main constructs regarding role theory are relevant: "role performance": the actual attitude of the person filling the role (Roberts, 1983), and "role perception" (Chaska, 1978), which describes the way the role holder and his/her role participants perceive the role and their expectation from it.

A "role model" demonstrates good role performance from which other actors can learn (Kemper, 1968). In nursing education, the midwifery preceptor is expected to act as a "role model" for her preceptees (Perry, 2009). In other words, a role model can be defined as "a person whose behaviour, example, or success is, or can be, emulated by others" (Retrieved form: http://www.dictionary.com based on Random House Unabridged Dictionary). The term "role model" was coined by Robert K. Merton, regarding socialization of medical students. Role models are people who act a successful examples by modelling required behaviours, skills and competencies (Kemper, 1968; Lockwood & Kunda, 1997). The development of competency and confidence among students is believed to be a result of their exposure to a qualified preceptor, i.e., a professional personality that is a good role model (Fluit, Bolhuis, Stuyt, & Laan, 2011). Preceptors were found to be central to the development of preceptee competency, self-esteem and confidence (Edwards, Smith, Courthney, Finlayson, & Chapman, 2004; Randel, 2001). Although there is no one model or set of qualities that define an "ideal" preceptor "role model", however, the three main qualities which appeared repeatedly in studies were: relationship with preceptees, professional competence, and personal attributes (Brown, 1981; Bergman & Gaitskill, 1990; Madhavanprabhakaran, Shukri, Hayudini, & Narayanan, 2013).

The inter-personal, professional and personal qualities of the preceptor.

Quality #1 - Relationship with the preceptee.

Developing a close and caring bond between preceptor and preceptee was found to be vital among general nursing preceptees (Gray & Smith, 2000; Lee, 1996; Neary, 1997); however, no studies on this relationship were found regarding midwifery preceptees and their preceptors. Strong interpersonal skills are necessary (Levy et al., 2009). A synthesis of qualities in preceptee-preceptor relationships suggests that preceptees valued the following in the preceptor: confidence, realistic expectations, honesty, accessibility, openness and availability (Bergman & Gaitskill, 1990; Madhavanprabhakaran et al., 2013).

Quality #2 - Professional Competence.

The preceptees expect their preceptors to be skilled practitioners, to keep up to date (Wealthall & Henning, 2012), and to demonstrate expertise in their field (Perry, 2009). One study noted that in Middle Eastern countries, preceptees believed that the preceptor’s clinical competence was the most important characteristic (Madhavanprabhakaran et al., 2013). Other qualities of professional competence are commitment to the preceptee and integration of theory into practice (Bergman & Gaitskill, 1990), interest in the preceptees (Levy et al., 2009), good communication skills with regular feedback (Gray & Smith, 2000; Letizia & Jennrich, 1998; Madhavanprabhakaran et al., 2013; Myrick, 2002; Myrick & Barrett, 1994; Myrick & Young, 2001), and inspiration of the preceptee to practice confidently in the clinical environment (Happell, 2009).

Quality #3 - Personal attributes.

Preceptors have a significant impact on preceptee performance and socialization in their role as nurses. Preceptees describe good preceptors as having a sense of humour and enthusiasm for teaching (Gray & Smith, 2000), knowing their limitations, and acting with a reasonable sense of professional integrity (Paton, 2009). Additionally, preceptees believe that preceptor flexibility creates opportunities for learning, helping them to cope in uncertain situations in a caring and open way (Dickson, Walker, & Bourgeois, 2006); moreover, preceptees state that they respect and appreciate preceptors with patience, non-judgemental and who understand when they ought to intervene.

Clinical learning environments (CLE's).

The CLE is comprised of an interactive network of forces that influence the students' clinical learning outcomes (Dunn & Burnnett, 1995), which not only encompass the geography and equipment of the clinical setting, but also include the atmosphere and people such as the staff, the patient, the nurse preceptor, and the nurse educator (Papp, Markkanen, & Von Bonsdorff, 2003).

CLEs vary; they can be challenging, unpredictable and stressful (Hosda, 2006). Unfortunately, the environments are not always supportive, but midwifery students are expected to adapt to new staff members and their new nurse preceptors. From studies reporting important CLE characteristics, six major dimensions have emerged: ward atmosphere, supervision by staff nurses, theory practice gap, peer support, student satisfaction, and supervision by clinical preceptors (Edwards et al., 2004; Lewin, 2007; Papp et al., 2003). The preceptorship model provides a supportive learning environment fit to the socialization process of preceptees into their professional role, combining theory and practice.

However, self-efficacy, organizational environments (CLE) in nursing education and support are crucial for the development of learning and making effective clinical decisions (Hagbaghery, Salsali, & Ahmadi, 2004).

VARK – Adult Learning and Learning Styles.

Midwifery preceptors who function as role models for their preceptees teach adult learners. Adult learning theory is widely known and based on the principle that learning should be "learner centred" (Knowles, 1980). I.e., preceptors who teach midwifery students must, on one hand take into account that the adult students have a wide life experience, and on the other that they are novices. However, identifying the preferred learning style is important for success in learning (Kocinski, 1984). According to Felder and Barnett (2005) and Fleming (2008) there are four major types of learning styles which are summarized in the acronym VARK: Visual (learning by seeing), Auditory (learning by hearing), Read/write and Kinaesthetic (learning by doing). Hardy and Smith (2001) argued, that learning styles between a preceptor and preceptee should be matched, particularly in the nursing preceptor-preceptee relationship (Alkhasawneh, Maryyan, Alashram, & Yousef, 2008; Mehan-Andrews, 2008; Zilembo & Monterosso, 2008). When student learning styles are compatible with teachers teaching styles, student's academic performance may increase (Othman & Amiruddin, 2010). However, no literature examining this relationship was found in the field of midwifery nursing education. Although the VARK questionnaire has been used to identify types of learning styles for the last 30 years (Peyman et al., 2014), so far, no studies have examined the connection between matching preceptor-preceptee learning styles and self-efficacy. The present VARK instrument presents 16 daily-life situations which require learning, but these situations are not relevant for nursing education in general and for the discipline of midwifery in particular.

Methodology

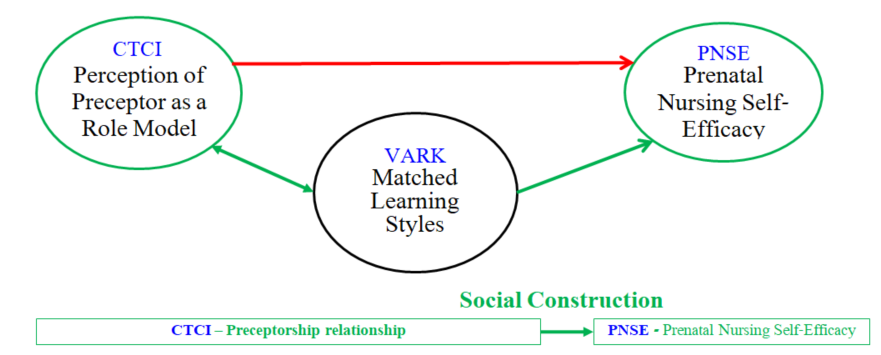

In this paper, we shall present the theoretical model (illustration 1) which was constructed following a literature review in order to examine the impact of matched preceptorship relations on midwifery education and student self-efficacy within midwifery education. According to this model, matched preceptor-preceptee learning styles influence the link between the quality of the preceptor-preceptee relationship (i.e., student-preceptee perception of the midwife-preceptor as a role model) and student self-efficacy.

In order to answer the research question, a vast comprehensive literature review has been conducted (Hart, 2018; Webster & Watson, 2002). The following procedures were conducted: (a) Mapping the main theoretical constructs which are related to the research topic; (b) Preparing a table which included the main definitions of each construct and identifying similarities and differences among the definitions and comparing them; (c) Identifying the core works (theoretical and empirical studies)by identifying the most frequently cited researchers, because these works have "a major influence methodologically and politically" (Webster & Watson, 2002, p. 24); (d) Summarizing the methodology and findings of main studies which examined the correlative and causal relationships among the research construct.

These procedures were conducted simultaneously and recursively, i.e. each work was read and summarized following these four procedures, and if needed reread in order to produce additional insights.

On the basis of the results of literature review – the theoretical model of the study was proposed.

Conclusion

According to the literature review, matched preceptor-preceptee learning styles may have a significant impact on the link between the quality of the preceptor-student relationship (i.e., student perception of the preceptor as a role model - CTCI) and student Prenatal Self-Efficacy - PNSE. Further research is needed in order to examine this theoretical model and to adjust the general VARK tool to midwifery education. Therefore, the following theoretical model was proposed on the basis of the literature review, in order to examine the impact of matched preceptorship relations of students' self-efficacy in midwifery education: (Figure

References

- Alkhasawneh, I. M., Maryyan, M. T., Alashram.S, & Yousef, H. Y. (2008). Problem based learning (PBL): Assessing learners' learning preferences using VARK. Nurse Education Today, 28(5), 572-579. https://dx.doi.org/10: 1016/J.nedt.2007.09.012

- Bandura, A. (1978). Self-efficacy: toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://dx.doi.org/10,1016/0146-642(78)90002-4

- Bandura, A. (2006). Guide for constructing self- efficacy scales. In F. Pajares & T. Urdan (Eds.), Self-Efficacy Beliefs of Adolescents (pp. 307-337). Greenwich, Connecticut: Information Age.

- Bandura, A., & Locke, E. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87-99.

- Berger, P. L., & Luckmann, T. (1966). The social construction of reality. USA: Penguin.

- Bergman, K., & Gaitskill, T. (1990). Faculty and student perceptions of effective clinical teachers: an extension study. Journal of Professional Education, 6(1), 33-44.

- Bharj, K. K., Luyben, A., Avery, M. D., Johnson, P., O'Connell, R., Barger, M. K.. (2016). An agenda for midwifery education: Advancing the state of the world's midwifery. Midwifery, 33, 3-6. DOI:

- Biddle, B. J. (1979). Role theory: Expectations, identities, and behaviors. New York: Academic.

- Biddle, B. J. (1986). Recent developments in role theory. Annual Review in Sociology, 12, 67-92.

- Brown, S. T. (1981). Faculty and student perceptions of effective clinical teachers. The Journal of Nursing Education, 20(9), 4-15.

- Carlson, E., Wann-Hansson, C. & Pilhammar, E. (2009). Teaching during clinical practice: Strategies and techniques used by preceptors in nursing education. Nurse Education Today, 29(5), 522-526.

- Chaska, N. (Ed.) (1978). The nursing profession: A time to speak. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Duffy, A. (2009). Guiding students through reflective practice - The preceptors' experiences. A qualitative descriptive study. Nurse Education in Practice, 9, 166–175.

- Dickson, C., Walker, J., & Bourgeois, S. (2006). Facilitating undergraduate nurses clinical practicum: the lived experience of clinical facilitators. Nurse Education Today, 26(5), 416-422.

- Dunn, S. V., & Burnnett, P. (1995). The development of a clinical learning environrment scale. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 22, 1166-1173.

- Edwards, H., Smith, S., Courthney, M., Finlayson, K., & Chapman, H. (2004). The impact of clinical placement location on nursing students' competence and preparedness for practice. Nurse Education Today, 24(4), 248-255. https://dx.doi.org/

- Felder, R. M., & Barnett, R. (2005). Understanding student differences. Journal of Engineering Education, 31(1), 57-72.

- Feldhusen, A. E. (2000). The History of Midwifery and Childbirth in America: A Time Line. Midwifery Today: the heart and science of birth. Retrieved from: https://midwiferytoday.com/web-article/history-midwifery-childbirth-america-time-line/

- Fleming, N. D. (2008). VARK. A guide to learning styles. Retrieved from http://VARK-learn.com

- Fluit, C, Bolhuis S, Stuyt P, & Laan R. (2011). The physician as teacher. Ways to measure the quality of medical training. Nederlands tijdschrift voor geneeskunde.155: A3233. PMid:21988753

- Gergen, K. J. (2008). Social Construction and pedagogical practice. Retrieved from: https://s3.amazonaws.com/academia.edu.documents/33329928/Social_Construction_and_Pedagogical_Practice.pdf?AWSAccessKeyId=AKIAIWOWYYGZ2Y53UL3A&Expires=1526201082&Signature=gBxuq84XFSNEzfWjZdARJbI4wkM%3D&response-content-disposition=inline%3B%20filename%3DSocial_Construction_and_Pedagogical_ Prac.pdf

- Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. New York: Anchor.

- Goldman, I., & Cojocaru, S. (2017). Upgrading learning in nursing preceptorship using a reflection tool. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences. Retrieved from DOI:

- Gray, M., & Smith, L. N. (2000). The qualities of an effective mentor from the student nurse's perspective: findings from a longitudinal study. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 32, 1542-1549.

- Hagbaghery, M., Salsali, M. & Ahmadi, F. (2004). The factors facilitating and inhibiting effective clinical decision-making in nursing: A qualitative study. BioMedical Central Nursing, 3(1), 1-11.

- Happell, B. (2009). A model of preceptorship in nursing: Reflecting the complex functions of the role. Nursing Education Perspectives, 30(6), 372-376.

- Hardy, R., & Smith, R. (2001). Enhancing staff development with a structural preceptor programme. Journal of Nursing Care Quality, 15, 9-17.

- Harre, R. & van Lagenhove, L. (1999). The dynamics of social episodes, in R. Harre, & L. van Langenhove, (eds.) Positioning theory: Moral contexts of intentional action. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hart, C. (2018). Doing a literature review. London: Sage.

- Hosda, Y. (2006). Development and testing of clinical learning environment diagnostic inventory for baccalaureate nursing students. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 56(5), 480-490. https://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j. 1365-2648.2006. 04048.x

- Jordan, R., & Farely, C. (2008). The confidence to practice midwifery: Preceptor influence on student self-efficacy. Journal of Midwifery and Women's health, 53(5), 413-420.

- Karimi, M. H., Dabbaghi,, F., Oskouie, F., Vehviläinen-Julkunen, K. (2009). Learning style in theoretical courses: Nursing students’ perceptions and experiences. Iranian Journal of Medical Education; 9, 41-54 (Persian)

- Kemper, T. D. (1968). Reference groups, socialization, and achievement. American Sociology Review, 33, 31-45.

- Knowles, M. S. (1980). The modern practice of adult Education: From pedagogy to andragogy (pp. 24-39). New York: Cambridge: The Adult Education Company.

- Kocinski, R. R. (1984). The effect of knowledge of one's learning style by freshman nursing students on student achievement (PhD Dissertation). New Jersey: Rutgers University.

- Lambert, V, & Glacken, M. (2006). Clinical education facilitators' and post-registration pediatric student nurses' perceptions of the role of the clinical education facilitator. Nurse Education Today, 26(5), 358-66.

- Lauder, W., Holland, K., Roxburgh, M., Topping, K., Watson, R., Johnson, M., & Behr, A. (2008). Measuring competence, self- reported competence and self-efficacy in pre-registration students. Nursing Standards, 22(20), 35-43.

- Letizia, M., & Jennrich, J. (1998). Development and testing of the clinical post-conference learning environment survey. Journal of Professional Nursing, 14(4), 206-213.

- Levy, L. S., Sexton, P., Willeford, S., Barnum, M. G., Guyer, M. S., Gardner, G., & Fincher, L. (2009). Clinical instructor characteristics, behaviors and skills in allied health care settings: a literature review. Athletic Training Education Journal, 4(1), 8-13.

- Lewin, D. (2007). Clinical learning environment for student nurses: key indicates from two studies over 25 years period. Nurse Education in Practice, 7(4), 238-246. https://dx.doi.org/

- Lockwood, P., & Kunda, Z. (1997) Superstars and me: Predicting the impact of role models on the self. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73, 91-103.

- Madhavanprabhakaran, G. K., Shukri, R. K., Hayudini, J., & Narayanan, S. K. (2013). Undergraduate nursing students' perception of effective clinical instructor: Oman. International Journal of Nursing Science, 3(2), 38-44.

- Murphy, C., & Kraft, L. (1993). Development and validation of the perinatal nursing self-efficacy scale. Scholary Inquiry for Nursing Practice, 7(2), 95-106.

- Myrick, F. (2002). Preceptorship and critical thinking in nursing education. Journal of Nursing Education, 41(4), 154-164.

- Myrick, F., & Barrett, C. (1994). Selecting clinical preceptors for basic baccalaureate nursing students: A critical issue in clinical teaching. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 19(1), 194-198.

- Myrick, F., & Young, O. J. (2001). Creating a climate for critical thinking in the preceptorship experience. Nurse Education Today, 21(6), 461-467. http//dx.doi.org.10.1054/nedt.2001,0593

- Nielsen, K., Finderup, J., Brahe, L., Elgaard, R. & Elsborg, A. M. Engell-Soerensen, V., … (2017). The art of preceptorship: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Practice, 26, 39-45.

- Othman, N. & Amiruddin, M. H. (2010). Different perspectives of learning styles from VARK Model. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 7, 652-660. Available online at www.sciencedirect.com

- Papp, I., Markkanen, M., & Von Bonsdorff, M. (2003). Clinical learning as a learning environment: student nurses' perceptions concerning clinical learning experiences. Nurse Education Today, 23, 262-268.

- Paton, B. I. (2009). Keeping the center of nursing alive: A framework for preceptor discernment and accountability. The Journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 40(3), 115-120.

- Perry, B. (2009). Role modeling excellence in clinical nursing practice. Nurse Education in Practice, 9, 36-44.

- Peyman, H., Sadeghifar, J., Kahajvikhan, J., Yassemi, M., Rasool, M., Yaghoubi, Y. M., &. Karim. H. (2014). Using VARK approach for assesssing preferred learning styles of first year medical sciences students: A survey from Iran. Journal of Clinical and Diagnostic Research, 8(8), GC01-GC04.

- Phillips, D. J. (2002). A discursive model of professional identity formation and cultural agency in midwifery education: A framework to guide practice. Doctoral dissertation, The University of Melbourne, Melbourne.

- Phillips, D. J., & Hayes, B. (2006(. Moving towards a model of professional identity formation in midwifery through conversations and positioning theory. Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 46(2), 224-242.

- Phillips, D., R., & Fawns, & Hayes, B. (2002). From personal reflection to social positioning: the development of a transformational model of professional education in midwifery. Nursing Inquiry, 9(4), 239-249

- Randel, J. (2001). The effect of 3 years pre-registration course on student's self- esteem. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 10, 293-300.

- Vladescu, C., Scintee, S. G., Olsavsky, V., Hernandez-Quevedo, C., & Sagan, A. (2016). Romania – Health system review. Health system in transition, 18(4). Retrieved from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27603897

- Wealthall, S., & Henning, M. (2012). What makes a competent clinical teacher? Canadian Medical Education Journal, 3(2), 141-145.

- Webster, J., & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26(2), xiii-xxiii.

- WHO (2018). Nursing and midwifery - WHO global strategic directions for strengthening nursing and midwifery 2016–2020. Summary of ICN-ICM-WHO triad meeting in Geneva, Switzerland, 16-19 May 2018. Retrieved from: http://www.who.int/hrh/nursing_midwifery/nursing-midwifery/en/

- Zulkosky, K. (2009). Self-efficacy: A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 44(2), 93-102.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Rapaport, Z., & Cojocaru, S. (2019). The Impact Of Matched Preceptorship-Relations On Midwifery Education Students Self-Efficacy. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 302-311). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.38