Abstract

The multi-dialogical approach (MDA) in the kindergarten aims to improve kindergarten children's social and communicative skills, for example: the ability to converse in dialogical discussion and actively participate in planning their activities and learning. When children participate in their learning, they can make an important contribution to the dialog because the children’s point of view is recognized, and the discussion can focus on their world and their way of thinking. This is one way in which the children can be included in the planning of their activities and in their learning. The article presents part of a research study investigating the development of social communication patterns among children in a multi-dialogical kindergarten. The article focuses on the children's participation in their learning according to the kindergarten multi-dialogical approach. The research drew data from participatory observation on children's participation in their learning. According to the multi-dialogical approach, children learn to take part in planning their activities and their learning; children's participation is observed during their daily involvement in the kindergarten routine, as well as in more complex activities, such as leading research processes and kindergarten projects. This forms the foundation for the multidialogical approach, allowing the child to practice dialog skills through dialogical discourse and to actively participate in their learning.

Keywords: Multi- dialogical approachchildren's participationchildren planning activitiesnegotiation

Introduction

This work describes the use of the multi-dialogical approach (MDA) in the kindergarten. It aims to examine the connection between the use of the MDA and the development of kindergarten children's social and communicative skills, for example: the ability to converse in dialogical discussion and actively participate in planning their activities and learning. Among other things, preschool education aims to allow the child to grow and to evolve into an involved citizen, who has the ability to judge and criticize and is a curious independent thinker, demonstrating initiative. The fundamental assumption of multi-dialogical education, which underpins this work, is that when a child learns about his world out of their own inner interest, the child will evolve into that type of adult. The aim of this study is to examine the core aspects of this educational method namely, the behavioural patterns and social communication processes of children who learn in a multi-dialogical kindergarten.

When children participate in their learning, they can make an important contribution to the dialog because the children’s point of view is recognized, and the discussion can focus on their world and their way of thinking. This is one way in which the children can be included in the planning of their activities and in their learning (Emilson & Johansson, 2009; Pramling-Samuelsson & Sheridan, 2003).

The qualitative part of the research was conducted in two parallel stages: participatory observations of 25 children learning in a kindergarten according to the MDA were filmed and transcribed. The researcher also conducted semi-structured interviews with 15 kindergarten teachers, seven of whom work according to the MDA and eight who work according to the traditional educational approach. To supplement data from the qualitative study, a closed-ended quantitative questionnaire was constructed and administered to 130 kindergarten teachers.

Multidialogical approach in the kindergartens

The Israeli kindergarten is an educational-learning framework. It aims to promote children’s development so that they can become active, initiating, decisive, independent and social individuals (Levine, 1989; Ministry of Education, 2010). Multi-dialogical education is based on the principles of dialogical education. Dialogical education involves the development of a culture of research for the children, while the educator listens to the children, asks them questions, mediates and documents their activity (Fiore & Suares, 2010). This strategy allows the children to conceptualize phenomena and situations that emerge from activity in their environment (Caspi, 1979). Multi-dialogical education involves the inclusion of the children as partners in decision-making about the kindergarten's operations, not only about academic issues but about all aspects of the kindergarten's activities. This decision-making, conducted through negotiation between the kindergarten teacher and the children (Efrat & Ungureanu, 2015), includes discourse relating to their behavioural norms, focuses of activity and how these should be promoted, how to celebrate holidays and the kindergarten way of life.

According to the multi-dialogical approach, the kindergarten staff employ attentiveness with regard to all aspects of the kindergarten, not only in spoken words. In practice, this approach is expressed by enlisting the children as partners in planning kindergarten activities, allowing them to instruct their peers in small groups and in the general meetings, encouraging them to provide feedback to other children on instructed activities, and through the kindergarten teacher’s personal meetings with them to plan activities that they will present (Firstater & Efrat, 2014).

Children's participation in learning and decision-making in the kindergarten

One of the prominent features of the use of the MDA in the kindergarten is that the children participate in the making of decisions concerning their daily activities. Their participation in decision-making allows the children to create their own open and significant world, as they express their opinions in the group. The inevitable question is whether such participation is actually possible at such a young age. However, some studies have supported the approach and demonstrated that kindergarten children are capable of reporting, analysing and reaching decisions on situations and problems that arise in the kindergarten. Additionally, they can lead and execute projects, debate issues that arise and guide others. In the context of the study, the children's participation in kindergarten decision-making is obviously not merely symbolic but is clearly real. It is manifested in the children's participation in determining rules of conduct in the different areas of the kindergarten and in their preparation and guidance of activities for the entire kindergarten. The children are partners in the choosing, planning, and leading of kindergarten projects according to their areas of interest, guiding meetings and group activities and managing discourse and debates about subjects that interest them (Danner & Jonyniene, 2012; Firstater & Efrat, 2014; Rinaldi, 2006). In the context of MDA it can be argued that of the genuine cooperation betwen the children, their peers and the kindergarten teacher, creates a sense of excitement concerning their learning and developing relations based on authentic communication between all those participating in the learning. Children-teacher relationships thus become meaningful human encounters based on shared discussion, experience and understanding (Efrat & Ungureanu, 2015; Fumoto, 2011).

In these encounters learning occurs through dialog between the participants, in which the children and teacher reflect on and assess the processes they have experienced and their own participation in these processes in order to improve in the future (Firstater & Efrat, 2014, Ben-Yosef, 2009). This is a long, and dynamic reflective process that may involve many people. The process involves both cognition and emotion and is expressed in curiosity and daring (Ben-Yosef, 2009). MDA education involves a pattern of interaction, characterized by the asking of questions relevant to a particular issue raised by the dialog participants, the children and the kindergarten teacher, by answers that are predetermined, and which are delivered during the dialog and can change the subject under discussion (Nystrand, Gamoran, Kachur, & Prendergast, 1997). The present study provides new understanding, indicating that this process is the product of a basic understanding that young kindergarten children possess knowledge and experience and they can use them to develop their own ideas and opinions and express them in dialog (Lansdown, 2001). This conclusion can perhaps alter perceptions of children-teacher relationships in education, when negotiation between all those participating in the learning process (Lyle, 2008).

Problem Statement

The gap in knowledge that this study aimed to fill is due to the fact that most studies, which have been conducted in the dialogical learning field in various countries have focused on elementary school children. Other studies, which related to kindergartens, have mainly examined interactions between the kindergarten teacher and the child (Fumoto, 2011) and the influence of mediated learning on children (Tzuriel & Shamir, 2007). However, as far as can be ascertained, there has been no investigation of the implementation of different educational approaches in early childhood or of their implications for the children and their development.

Research Questions

The research questions were: (1) which unique social, behavioural and interpersonal communication patterns occur among kindergarten children in a multi-dialogical kindergarten? And (2) which social, communication and interpersonal differences will be found between children educated in multi-dialogical kindergartens and children educated in traditional kindergartens?

Purpose of the Study

The research aimed to examine the development of children’s social-communication patterns, such as initiative, leadership and participation in their learning in a multi-dialogical kindergarten.

4.1. Research hypotheses

Considering the background provided by the above literature review, the following research hypotheses guided the research:

The social and communication patterns of children educated in multi-dialogical kindergartens will differ from those of children educated in traditional kindergartens.

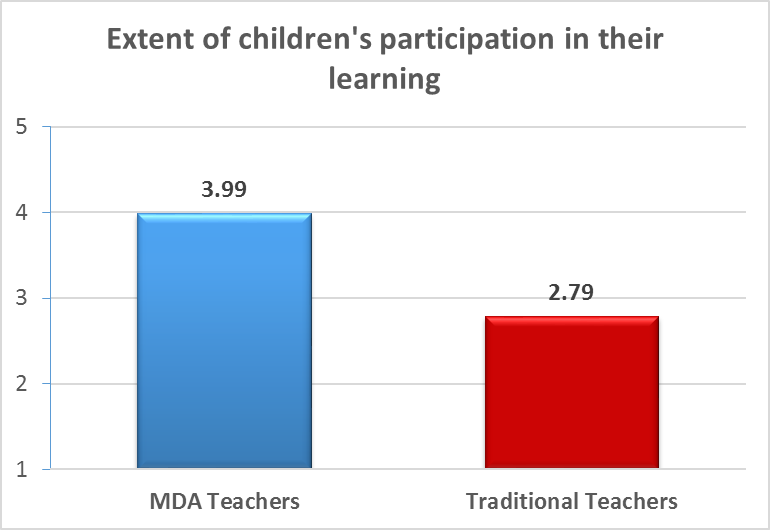

Differences will be found mainly in the extent of children's participation in their learning between multi-dialogical kindergartens and traditional kindergartens...

Research Methods

Participants

The research population included three samples: The first group included 25 children aged 3-6; the second group included 15 kindergarten teachers and the third group included 130 kindergarten teachers. The participants were selected according to the purposive sample method (Bocos, 2007; Stake, 1995; Shkedi, 2003; Mason, 1996).

Instruments

A mixed-methods approach was chosen to collect and analyse both quantitative and qualitative data. Part of the qualitative research was an action research study. This included the use of participatory observations of the kindergarten activities performed by the researcher in a multi-dialogical kindergarten. some of which were documented in writing while others were video-filmed and transcribed. These observations were employed to clarify the different types of kindergarten children's interpersonal communication. To gather qualitative data, the research also employed semi-structured interviews and closed questionnaires. Semi-structured interviews were conducted with a small number of kindergarten teachers in order to examine how the multi-dialogical approach (MDA) was applied in kindergartens. A closed-ended questionnaire constructed on the basis of the content analysis of data from the semi-structured interviews. Data from MDA kindergarten teachers was compared with data elicited from traditional kindergarten teachers. Quantitative data was collected from closed questionnaires administered to a large sample of kindergarten teachers, to identify and explore ways to implement the MDA in kindergartens. T-tests and the Chi squared test (χ2) were used for the two independent samples in the section describing the sample in order to examine whether there were significant differences in the constant socio-demographic characteristics of the two groups, such as years of experience in teaching, number of children attending the kindergarten etc.

Procedure

Mixed-methods data-collection tools were chosen to collect quantitative and qualitative data that could be used to respond to the research question. Part of the qualitative data was collected through action research, including transcribed videotapes and protocols from structured participatory observations performed in a multi-dialogical kindergarten. These observations were used to clarify the different types of kindergarten children's interpersonal communication. In addition, the research employed semi-structured interviews and closed questionnaires. Semi-structured interviews were administered to a small number of kindergarten teachers in order to collect qualitative data that would help to examine the effect of application of the MDA in kindergartens. Closed questionnaires were administered to a large number of kindergarten teachers in order to collect quantitative data that would help to identify and explore ways to implement the MDA in kindergartens. The qualitative research data was analysed by qualitative content analysis based on the formation of categories, while the quantitative data underwent statistical analysis using t-test variance tests in a purposeful sample.

Data analysis

The qualitative research data underwent content analysis based on the formation of categories. The quantitative data was analysed statistically with the help of t-test variance tests in a purposeful sample.

Research limitations

The qualitative study was ethnographic, providing a low level of objectivity. The researcher therefore used a wide range of sources of information to increase the data's validity. In addition, in the participatory observations, the researcher’s presence might have influenced the participants’ behaviour. However, in the many hours of observation, the participants became used to the researcher and ignored her. In semi-structured interviews, participants tend to want to please the interviewer; the researcher therefore avoided judgmental reactions.

Findings

Analysis of the qualitative data that emerged from the filmed participatory observations in the multi-dialogical kindergarten indicated that the during the children’s activities, the children delved deep into their fields of interest as part of the learning patterns characteristic of a kindergarten using the MDA. Evidence of this appeared in Film 10 in which Marie (5.9) investigated the subject of native American Indians and guided a group of children on this subject. Marie shared her knowledge with the children and the children saw her as having expertise in this field.

Marie (5.9) opens a file that she has prepared on the subject of the Indians, she shows it to the group and says: “Here these are Indians, they live in tepees but they don’t only live there, they sleep there, they eat there, they light bonfires and play on bamboo pipes, they eat buffalo, and they make combs from the buffalo’s bones”.

Dealing with this field of interest stimulates the children to ask the girl with the knowledge questions:

Ziv (5.11): “Marie, that mask, that head – is it one of a real animal?”

Marie (5.9): “Yes …”

Yahel (5.1): “Marie, who are they fighting? You still haven’t explained it to us?”

Marie (5.9): “I’ll explain it to you now. They fight with traders and they fight about trades…”.

Yahel (5.1): “What are trades?”

Marie (5.9): “Trades are for example, if you want me to give you something, then I give you [something] and you give it to me”.

It seems that when the kindergarten works according to the MDA, it is characterized by the children’s desire to develop their knowledge of their field of interest in depth. The children are clearly able to explain and to transmit knowledge that they have acquired to their peers. Moreover, the other children relate to their friends who are leading the session as the source of knowledge and ask them questions on different subjects as part of the social-communication patterns developed in the kindergarten.

Analysis of the qualitative data from the interviews with the teachers indicates that when the MDA is used in a kindergarten, the fact that children learn about and go deeper into their fields of interest means that they develop a strong curiosity to learn. Noam explained: “The children are far more open-minded and have a desire to learn because the learning takes place in their fields of interest…Learning in this manner responds to the children’s needs”. Carmel noted that “the learning in the kindergarten should not only come from above, from the teacher” and Liron said: “I really pay attention and observe which contents interest the children”. Anat added: “When the learning comes from the child, and interests the child, when it is the need of the child, as happens in the MDA, then it will be much more significant”. So that “I think that it is more correct to learn out of interest, and out of meaning, especially in our times, when knowledge is so accessible” added Noam.

The multi-dialogical kindergarten is characterized by the fact that its contents are constructed in line with the children’s fields of interest. The teacher identifies these fields by paying close attention to the children and observing their activities. This produces deep and meaningful learning and constitutes part of the social-communication patterns that develop in the multi-dialogical kindergarten.

Analysis of the quantitative data from the questionnaire revealed significant differences between the reports concerning the extent of children’s participation in their learning processes of MDA teachers and traditional teachers. MDA teachers gave higher grades for the level of children’s participation in their learning than the grading given by traditional teachers (3.99 in comparison to 2.79 respectively, t=8.34, p<0.01). More specifically, it was found that the MDA teachers gave significantly higher grades for the level of children’s participation in the different learning processes examined in the questionnaire in comparison to the grading given by traditional teachers.

Conclusion

The findings reveal correlations between the implementation of the MDA in kindergartens and the development of the kindergarten children's social-communicative patterns.

Significant differences were found between the evaluations of children's participation in their learning processes by the MDA teachers and the evaluations of the traditional teachers. This participation depends on the teacher’s approach, to what extent the teacher facilitates the children's participation, whether the contents and the way in which they are handled are based principally on her choices or on the children’s areas of interest and initiatives. In a traditional kindergarten, children also participate in their learning processes but the contents and he ways in which they handled are mostly the result of the teacher’s choices, there is significantly less participation by the children. This finding is supported by previous research indicating that children’s participation in their activities and learning in the kindergarten allows them to gain valuable social abilities experience including the skills of attentiveness and involvement, expressing a personal opinion, knowing how to share their experience with their friends, practicing decision-making , learning how to negotiate and learning to wait for their turn in a dialog and how to share things with friends (Clark & Moss, 2005; Leinonen & Venninan, 2012; Venninen, Leinonen, & Ojala, 2010). In this sense it is noted that all children can, in fact, participate in their learning; though of course this depends on the teacher’s approach and the extent to which she is willing to allow this (Nyland, 2009). This is expressed in the preparation of the learning curriculum, which may simply be a set of facts that everyone must know with very little choice or which can become a genuine learning curriculum based on the child's interest and investigation and relying on the child’s strengths (Gardner, 1996). To summarize: Social-communication patterns such as involvement, the ability to express oneself and to share experience and declare a personal opinion, ability to negotiate, to share, and to make decisions are shaped and depend on the way in which the kindergarten's learning curriculum is constructed and on the extent to which children participate in its planning and in the learning in the kindergarten.

Research significance

The significance of the research lies in its ability to inform a change in the approach to early childhood education and daily practice in the kindergarten, using the MDA to offer a foundation for the promotion and shaping of social communication patterns among early childhood children learning in the kindergarten. This is the substance of the multi-dialogical kindergarten.

To apply this approach the teacher needs to increase her own awareness regarding the substance of attentiveness in the educational act, and to learn how to apply this attentiveness at her own personal level and to guide the staff and children to use this strategy in the kindergarten.

References

- Ben-Yosef, A., (2009). Circles of connection: Concerning the fostering of a discourse culture in a humanistic educational institute. Rannana: MOFET Institute. [Hebrew]

- Bocos, M., (2007). The theory and praxis of pedagogical research. [Teoria şi practica cercetării pedagogice]. (in Romanian), Cluj-Napoca, Editura Casa Cărţii de Ştiinţă.

- Caspi, M., (1979). Education tomorrow. Tel Aviv: Am Oved. [Hebrew]

- Clark, A. & Moss, P., (2005). Spaces to play: more listening to young children using the Mosaic approach. London, National Children’s Bureau.

- Danner, S. & Jonyniene, Z., (2012). Participation of children in democratic decision-making in kindergarten: Experiences in Germany and Lithuania. Socialinis Darbas/Social Work, 11, 411-420.

- Efrat, M. & Ungureanu, D., (2015). Is the egg spoiled? A big question from a small child. Proceeding of the International Conference on Education Reflection and Development. Romania: Cluj-Napoca.

- Emilson, A. & Johansson, E., (2009). The Desirable toddler in preschool: Values communicated in teacher and child interactions. In D. Berthelsen, J. Brownlee & E. Johansson (Eds.), Participatory learning in the early years: research and pedagogy, London: Routledge.

- Fiore, L. & Suares, S.C., (201)0. This issue. Theory into Practice, 49(1), 1-4.

- Firstater, E. & Efrat, M. (2014). Social communication patters of children in a kindergarten operating according to the dialogical education approach. Rav Gvanim, Research and Discourse, 14, 11-48. Under the auspices of “Study and Research in Teacher Training”, Jerusalem: Ministry of Education and Gordon Academic College of Education. [Hebrew].

- Fumoto, H., (2011). Teacher–child relationships and early childhood practice. Early Years, 31, 19-30.

- Lansdown, G., (2001). Promoting children’s participation in democratic decision-making. Florence.

- Leinonen, J. & Venninen, T., (2012). Designing learning experiences together with children. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 45, 466-474.

- Levine, G., 1(989).Another kindergarten. Tel Aviv: Ach. [Hebrew]

- Lyle, S., (2008). Dialogic teaching: Discussing theoretical contexts and reviewing evidence from classroom practice. Language and Education, 22, 222-240.

- Mason, J. ( 1996). Qualitative researching. London: Sage Publications.

- Ministry of Education, (2010). Guidelines for educational work in kindergartens. Jerusalem: Department for Pre-Primary Education, Ministry of Education. [Hebrew]

- Nystrand, M., Gamoran, A., Kachur, R. & Prendergast, C., (1997). Opening dialogue: Understanding the dynamics of language and learning in the English classroom. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Pramling-Samuelsson, I. & Sheridan, S., (2003). Participation as value and pedagogic approach. Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige, 8(1–2.), 70-84.

- Rinaldi, C., (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia. London, Routledge.

- Shkedi, A., (2003). Words that attempt to touch, Qualitative research - Theory and implementation. Tel Aviv: Ramot. [Hebrew]

- Stake, R. E., (1995). The art of case study research. London: Sage Publications.

- Tzuriel, D. & Shamir, A., (2007). The effects of Peer Mediation with Young Children (PMYC) on children’s cognitive modifiability. The British Psychological Society, 77, 143-165.

- Venninen, T., Leinonen, J., & Ojala, M. (2010). Parasta on, kun yhteinen kokemus siirtyy jaetuksi iloksi–Lapsen osallisuus pääkaupunkiseudun päiväkodeissa. Tutkimusraportti.[When the shared experience transforms a collective joy”–Children’s Participation in Day Care centers. Research report], Helsinki: SOCCA-Pääkaupunkiseudun sosiaalialan osaamiskeskus., 3.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Efrat, M. (2019). Childrens Participation In Their Learning In The Kindergarten Multi-Dialogical Approach. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 244-252). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.31