Abstract

The Israeli society is multicultural and consequently numerous inter-cultural issues in various contexts are involved in the Israeli education system. This paper focuses on the issue of inter-culturalism that constitutes a central and meaningful part of organizational change processes transpiring in schools. The northern district of the Ministry of Education is characterized by multiculturalism (Jewish, state-religious, Arab, Bedouin, Druze and Circassian sectors). As such, its motto has been nurturing quality and organizational excellence that will entail the organization growth and excellence. Hence, the district adopted the European model of quality and organizational excellence (E.F.Q.M). This facilitates implementation of organizational change processes designed to achieve constant improvement and enhancement of learners’ attainments and services provided to customers. The model was assimilated in schools from all sectors. These schools underwent a 2-year process, after which they were recognized as “committed to excellence” by the E.F.Q.M international organization. The E.F.Q.M model constitutes an “organizational umbrella” that adapts itself to each organization. It helps organizations to lead change processes according to their nature and specific needs, aiming to achieve excellence and constant improvement. In this paper I review the inter-cultural issues related to the assimilation of the model in the chosen schools. The paper is grounded in the concept that the inter-cultural environment involved in the E.F.Q.M assimilation affects the process and the extent of its success. Consequently, it is necessary to clarify the inter-cultural issues prior to the introduction of the model in order to guarantee an effective implementation in the assimilating schools.

Keywords: EFQMinter-culturalismmulti-culturalismArab society in IsraelExcellenceeducation system

Introduction

The world in which we are living today has become open to everyone. The term ‘national, homogeneous and one-cultural state’ has increasingly faded and, at the same time, multiculturalism is turning into the key feature of societies around the globe. In the present age, most countries are characterized by a significant ethnic differentiation, either racial or religious, that is reluctant to disappear. This differentiation has spontaneously converted these states into multicultural or multinational societies (Tully, 2001).

Before delving deeper into the issue of multiculturalism, I should start by conceptualizing the term ‘culture’. This term defines a group of people who share values, customs, norms, behavioral patterns and worldviews (Lum, 1999). On the other hand, a multicultural society is characterized by differentiation and numerous lifestyles. This leads to a dialectic tension between the tendency towards convenience facilitated by the similar and familiar and the inconvenience created by the unfamiliar, unknown and sometimes even unacceptable. These tensions can entail confusion, disruption and insecurity, manifested by withdrawal, objection and introversion. Converse reactions can be for example openness, interest and acceptance (Shemer, 2009).

Israel is considered as an immigration-absorbing state that was founded in a country with a pre-existing culture. Since its foundation, Israel has been absorbing various populations from all over the world. This continuously confronts it with a reality of multiculturalism that challenges the existing social order. Israel is required to cope with special problems typical of the absorbed society, while taking into consideration the cultural, ethnic and value-oriented elements of each group. At the same time, it has to re-examine the relation between its collective identity, its citizenship and the economic status of its members as well as the principles of justice that it should embrace (Bashir, Ben-Porat, &Yona. 2016).

The continuous immigration processes lead to cultural differentiation within a heterogeneous society. This is due to the fact that each absorbed population adds values and traditions to the existing socio-cultural texture. This obliges us to acknowledge these inter-cultural differences and get thoroughly acquainted with them even before starting any meaningful process in order to guarantee its success. The education system is one of the main systems which must put an emphasis on the issue of inter-culturalism since it is the system that absorbs, shapes and educates the generations of society. In Israel, it is evident that the inter-cultural reality with all its complexity is a challenge to the country. As a result, many researchers have decided to engage in this issue.

James Banks (1996) relate to the connection between the state of nationality and the characteristics of a multicultural society and the educational practice. They maintain that we should relate to the multicultural contents and competences in order to communicate with others. Hence, the values of justice and equality should be implemented through multicultural education that integrates theory and practice. Such form of education can facilitate the liberation of the oppressed minority groups as well as the establishment of a democratic and just society.

Most of the studies of multicultural policy in education or of education for multiculturalism were conducted at the class level. They discussed topics such as the desirable learning contents, the values that should be inculcated or the attitudes of different sectors towards each other. The multicultural reality undoubtedly determines various inter-cultural issues in society in general and in the education system in particular. For example, language, religion and ceremonies, appointment of officials, design of the learning space and others.

Mall (2000) argues that ‘multiculturalism’ mainly refers to interactions between different cultural communities that function within the same framework. It is based on the assumption that we wish to understand and be understood. The multicultural approach is oriented at conducting a dialogue for the purpose of getting acquainted with the other. This encounter between traditions allows an intermediate space that entails insights and experiences. If we apply this approach to the education system, then we see that the education system is one of the most important frameworks for creating this inter-cultural space. This is due to the fact that it allows the manifestation of these inter-cultural issues as well as the acquaintance with others.

In this paper I will review the inter-cultural issues that resulted from the multicultural space and were involved in the process of assimilating the E.F.Q.M European model of organizational excellence. The main argument of the paper is that the inter-cultural environment is implicated in this process, playing a part in the E.F.Q.M assimilation. Hence, these issues should be clarified in order to guarantee a successful implementation of the model in the chosen schools. I should point out that this paper is part of my doctoral thesis entitled ‘The effect of the process of assimilating the E.F.Q.M organizational excellence model on the change of organizational culture in the Arab sector schools’.

Main Body

The Israeli education system

Education constitutes the basis of every society, particularly if this concerns education of a minority within a multi-national and multicultural society (Abu-Asbah, 2006). The State of Israel enacted the State Education Law in 1953. This law regulated the structure of state education in Israel in two main currents: state-education and religious-state education (Golan-Agnon, 2004; Jabarin & Agabaria, 2010). About 76% of the comprehensive student population in the academic year 2016/17 studied in the Hebrew education framework and approximately 24% in the Arab education framework. The number of learners in the Arab education framework related to students in the Arab, Druze, Bedouin and Circassian sectors (Ministry of Education, 2017a).

Between the years 2007-2017, the number of students in the Arab sector grew by 5% and is today approximately 70% of the entire student population of the primary Arab education framework. The Bedouin sector grew by 16% and is today about 22% of the total student population. Conversely, the Bedouin and Circassian sectors decreased by 3%, amounting today to 7% of the total student population in the primary Arab education (Ministry of Education, 2017b).

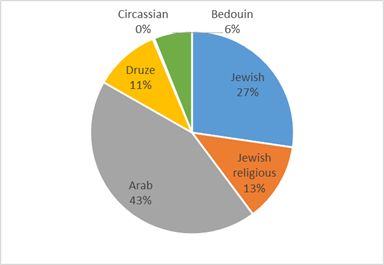

The Ministry of Education in the State of Israel is divided into five regions: southern, central, Tel Aviv, Haifa and northern regions. The northern region is the largest in terms of geographic deployment and sector distribution. The sectors in the regions are distributed as seen in Figure

In light of the ethnic complexity of the Israeli society and due to the sectorial education system that encompasses a cultural variety, the northern district has defined as its motto the cultivation of the issue of organizational quality and excellence. For that purpose, it decided to work according to the European model of organizational quality and excellence – E.F.Q.M.

The E.F.Q.M model

The E.F.Q.M organizational excellence model implemented by the European Foundation for Quality Management, has become the most important source for European organizations that aspire to achieve not only quality but also excellence.

The E.F.Q.M organization was founded in 1989 as a non-profit association. Fourteen CEOs of European organizations decided to serve as the motivating force for sustainable excellence in Europe. Following the organization success, it was adapted in 1995 also to public sector organizations. Today, the E.F.Q.M system is embraced by excelling global organizations of all sizes and all sectors, both private and public. It comprises over 700 organizations in and outside Europe and assists more than 30,000 organizations in their quest for excellence through their self-examination as well identification of their improvement and planning opportunities. Moreover, the E.F.Q.M organization grants the yearly E.F.Q.M Excellence Award to organizations recognized as excelling (Legenvre, Mallinder, & Woolley, 2006).

The E.F.Q.M model posits that there are different approaches to organizational excellence. Assessment according to this model is done by analysing the relation between what the organization does (the model criteria: leadership, strategy, people, alliances, resources and processes, products and services) and the results that the organization can obtain for its customers, employees, society and other key results (E.F.Q.M, 2010).

The E.F.Q.M model in the education system

In order to excel from an academic point of view, schools should be adapted to the students’ developmental needs and underscore social equality. They have to comprise organizational structures, mechanisms and quality-oriented processes. At present, the organizational excellence model is assimilated in schools around the globe: Spain, United States, Arab countries, Egypt and so on.

In Israel, the model was introduced in 2011 into the northern district of the Ministry of Education. To date, 45 schools have joined the process, 15 of them in the Arab sector (divided into Arab, Bedouin and Druze schools).

The schools are undergoing a 2-year long process. During this period, they diagnose by means of a self-assessment test their points of strength and points to be strengthened according to the nine criteria and sub-criteria of the model. Based on the results, the school designs a systematic process for improving the educational and organizational practice, aiming to provide optimal results to the customers who are basically their students.

After completion of the process, the C2E Committed to Excellence is examined according to the model. The examination is performed by a qualified reviewer on behalf of the E.F.Q.M organization. It is carried out through perusal of attesting documents, presentation of the improvement team results, focus group with the management team and employee representatives in order to check to what extent the values of excellence have been assimilated. At the end of a full day of examination, the reviewer fills in a questionnaire that sums up the extent of assimilation based on the model criteria. The score of 3 and above in all the parameters implies that the school has successfully passed the examination and it is awarded a C2E certificate. Schools that have proven compliance with the values of quality and excellence receive a European excellence certificate of C2E1 (Committed to excellence).

Please note that the schools that have joined the program should have a well-established organizational infrastructure, namely an active management team, school vision and work plan. These are prerequisites for undergoing a process of in-depth diagnosis of the school organizational culture and accordingly they undergo change processes.

Argyris and Schon (1978) defined types of change: change of the first degree or of the first order and change of the second degree or of the second order. The change that the E.F.Q.M model leads in the schools is a change of the second degree since it relates to the core, foundations, paradigm. Such a change undermines the perception, structure, assumptions, values, goals or direction underpinning the organizational or individual framework, although the organization or the individual maintain their self-identity. The assimilation process allows a new breakthrough, changing the system itself from its basis. This change involves a leap and the organization starts its journey of constant improvement towards organizational quality and excellence.

The process of assimilating the change according to the model is supported by a team of qualified consultants, accompanying the school with an intensive and continuous work. Most of the consultants belong to the Jewish sector and they accompany also Arab sector schools. This leads to a unique inter-cultural encounter, particularly when this concerns an in-depth and comprehensive change process. Leading an in-depth change in an inter-cultural encounter sets complicated challenges that should be addressed for the success of the process.

The consultants have to be sensitive to the inter-cultural issues that might emerge during the process. Lum (1999) and Raheim (2002) related to the term ‘cultural competence’ that both the professionals and the schools require for the purpose of providing an effective service to customers from different culture. People with s cultural competence have inter-cultural features that are manifested by openness to the thoughts, feelings and behaviors that are unfamiliar in their own culture. They try finding the unifying factor between people (Grant & Ladson-Billings, 1997). In order to be culture-sensitive, professional should thoroughly study the organization which they assist. In our case, the consultants have to look into the schools they accompany, clarify all the inter-cultural issues and be sensitive to them. As mentioned above, multiculturalism leads to a challenging inter-cultural encounter and requires diving into its depth in view of understanding and leveraging it for the success of the process.

Regarding the process of assimilating the E.F.Q.M model in the schools and the ensuing inter-cultural encounter that is an inseparable part of the process, we can elucidate that this encounter necessitates mutual acquaintance in the existing space, making the transition from multiculturalism to inter-culturalism. Both sides, i.e. the accompanying consultants (on the one hand) and the school team (on the other) must launch an open and safe communication channel aiming to get to know the other. This will enhance the introduction of the organizational change process (E.F.Q.M) in a more guaranteed form.

Mutual acquaintance with inter-cultural issues, such as: dress code, sensitivity to language, customs, social tradition and so on, can rationalize the process and reduce the objection to it. This can be exemplified by a conversation that I conducted with one of the quality coordinators who leads the process in her school. The coordinator told me that on a certain occasion she had to be absent for several days due to preparations towards her relative’s wedding. This caused a delay in a significant process implemented at this time. The accompanying consultant failed to understand the relation between a wedding and being absent from work for several days?! An open conversation between the two sides clarified that in the Arab/Bedouin tradition, the wedding event lasts several days and nights and necessitates preparation and participation of all the family members. This inter-cultural gap was not obvious and an inter-cultural discourse and communication was needed in order to understand and accept it. In this case, the discourse enabled the accompanying consultant to understand and respect the differentiation, bridging the inter-cultural gap between the two sides.

According to Healy (1998), the inter-cultural communication should be consolidated as a matter of routine in the inter-cultural encounter, while highlighting the point of mutual understanding. He suggests four basic conditions for a successful inter-cultural encounter:

1.Tolerance and mutual respect.

2.Equal conditions that enable the participating cultures to express their voice even in their own language.

3.Mutual trust free of prejudices.

4.Cultural learning following a process of inter-cultural exchange.

In order to illustrate the importance of the conditions presented by Healy (1998), I will present an example that is related to the matter of mutual respect. When consultants from the Jewish sector accompany an Arab sector school, a gap of languages is created. The Hebrew-speaking consultants do not speak Arabic whereas the school team speaks both languages! In such a case, the school team respects the consultants, allowing them to speak in their own language (Hebrew) and at the same time understands and accepts the consultants’ difficulty to understand the school Arabic language. Hence, the discussion is conducted in Hebrew that is the language understood by both sides–a lingua franca.

Another example refers to the issue of dress code. The schools participating in the assimilation program belong to a wide and varied range of cultures. This requires suitable behavior and dress code that show respect to the other side. For example, secular consultants must maintain a modest and respectful dress code when visiting a Jewish religious school, an observant Jewish village or a Druze community that belongs to a conservative sector. This respectful attitude opens a safer communication channel between the two sides and increases their mutual trust relations. On the other hand, lack of such attitude inhibits a priori the process and blocks the communication between them.

This inter-cultural encounter creates a common culture that respects multiculturalism, nurtures and cultivates it, leading to a wider awareness and opening new cultural horizons. This is a prerequisite for every multicultural society (Parekh, 2000).

A significant stage in the process of the E.F.Q.M assimilation is the self-examination during which the organization members decipher the school organization according to the nine criteria of the model, the principal being excluded from the process. The process is most meaningful and sensitive because it includes the element of loyalty to the leader! This aspect is even stronger when more conservative sectors are concerned. The issue of multiculturalism is also introduced into this process and at this point the consultants must be culture-sensitive. Throughout the process they should be aware of this issue that might constitute an emotional inhibitor for the employees and might prevent transparency and open collaboration.

At the same time, this process teaches and opens thinking horizons for both sides. Through the model, the employees are exposed to an open European culture that enables constructive criticism. The very fact that they are in a situation whereby they get a mandate to examine their leader is not typical of the Arab culture in general and of the conservative culture in particular. On the other hand, this space enables the consultants to examine another cultural value that is different from their own

Methodology

A systematic review of the relevant literature was employed.

Conclusion

To sum up, the review presented in this paper illustrates that the diversified inter-cultural space affects the schools that have assimilated the E.F.Q.M model and thus are leading a change process. This is particularly essential when different levels of inter-cultural gaps are involved. On the one hand, the model is taken from a European culture and on the other there is an inter-cultural gap between the consultants from one culture and schools with their own cultural diversity (Jewish, religious, Arab, Druze and Bedouin).

These findings indicate that the impact of the inter-cultural issues on the effectiveness of change process is high. Consequently, and in order to guarantee an effective process, inter-cultural sensitivity integrated with holistic and comprehensive thinking should be embraced. It is recommended taking into consideration the inter-cultural challenge, examine it with a critical eye, pay attention to covert layers and clues that might surface throughout the process. This work requires that, throughout the process, we constantly cope with, understand and accept the inter-cultural changes. This will facilitate a better guaranteed and instructive organizational change process for all those involved in the process.

References

- Abu-Asbah, H. (2006). Inhibitors to equality of the Arabs in Israel. Jerusalem: Floersheimer studies Institute for Political Studies. [Hebrew]

- Argyris, C., & Schon, D. (1978). Organisational learning: A theory of action perspective. Reading, Mass: Addison-Wesley.

- Banks, J. A. (1996). The Historical Reconstruction of Knowledge about Race: Implications for Transformative Teaching. In J. A. Banks (Ed.), Multicultural Education, Transformative Knowledge and Action: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives (pp. 64-88). New York, NY: Teachers College Press, Columbia University.

- Bashir, B., Ben-Porat, G., & Yona, Y. (2016). Public policy and multiculturalism. Jerusalem: Van Leer Institute. [Hebrew]

- EFQM. (2010). Quick Check- User Guide – EFQM Model.2010 Version. Retrieved form https://www.emeraldinsight.com/doi/abs/

- Golan-Agnon, D. (2004). Why are Arab pupils in Israel discriminated? In D. Golan-Agnon (Ed.), Inequality in Education (pp. 70-89). Tel Aviv: Babel Publishers. [Hebrew]

- Grant, C.A., & Ladson-Billlings, G. (1997). Dictionary of multicultural education. Phoenix, AZ: Oryx Press.

- Healy, P. (1998). Dialogue across Boundaries: On the Discursive Conditions Necessary for a 'Politics of Equal Recognition'. Res Publica, IV(1), 59-76.

- Jabarin, Y., & Agabaria, I. (2010). Education on hold: Government policy and civil initiatives for the promotion of Arab education in Israel. Nazareth & Haifa: Haifa University, ( Doctoral Dissertation) - Arab Centre for Law and Policy and the Faculty of Law. [Hebrew].

- Legenvre, H., Mallinder, L., & Woolley, J. (2006). Above the Clouds: A Guide to Trends Changing the Way We Work: a Project. Greenleaf Publications.

- Lum, D. (1999). Cultural competence practice: A framework for growth and action. Pacific Grove: Brooks / Cole Publishing Company.

- Mall, R. A. (2000). Intercultural Philosophy, New York: Rowman& Littlefield.

- Ministry of Education (2017a). Document specifying the development of the education system: Facts and figures. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education. [Hebrew]

- Ministry of Education (2017b). Development of the education system: Statistical data. Jerusalem: Ministry of Education, Administration of Economy and Budgets, Economy and Statistics Section. [Hebrew]

- Parekh, B. (2000). Rethinking Multiculturalism. Cambridge, MASS: Harvard.

- Raheim, S. (2002). Cultural competence: A requirement for empowerment practice, pp. 95-107. In M. O’Melia & K. K. Miley (Eds.), Pathways to Power: Readings in Contextual Social Work Practice. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Shemer, O. (2009). From multiple cultures to multiculturalism. Professional challenges in a culture-sensitive work with children and their parents. Eshlem: EtSadeh. [Hebrew]

- Tully, J. (2001). Introduction. In A. G. Gagnon & J. Tully (Eds.), Multinational Democracies (pp. 1-34). Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press,

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Qadora, M., & Chis, V. (2019). Inter-Culturalismas A Key Factor In Assimilating The Efqm Model In Israeli Schools. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 236-243). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.30