Abstract

This article deals with the need to train teachers who teach in educational frameworks for at-risk youth. It is becoming apparent that teachers of at-risk youth require special training and specialization due to the unique characteristics of the population they teach. Those unique characteristics include, among others, tendency to violent behaviour, low socio-economic income level and low self-esteem. This article discusses this argument while reviewing the difficulties of teachers in schools in which the student population is defined as socially excluded at-risk youth. The first part of the article defines at-risk youth and introduces the different frameworks that accommodate students who dropped out of the mainstream education system. The second part deals with the characteristics of these students and the difficulties faced by the teaching staff teaching this population. After reviewing the characteristics and difficulties, the “cycle of exclusion in education” is presented as the link between the characteristics of excluded at-risk students and the difficulties faced by the teachers who teach this population. The description of the students’ characteristics, teachers’ difficulties, and “cycle of exclusion” serves as the basis for the assertion presented at the beginning of this article that special training and specialization are required for teachers of at-risk youth.

Keywords: At-risk youthsocially excluded youthcharacteristics of at-risk youthself-efficacyself-confidenceteacher training

Introduction

Teachers of at-risk youth need special training and specialization due to the unique characteristics of the population they teach. This article will discuss this assertion while reviewing the difficulties of teachers in schools where the student population is defined socially excluded at-risk youth. The first part of this article will define at-risk youth and the different frameworks into which students who dropped out of the mainstream education system are integrated. The second part will deal with the characteristics of these students and the difficulties faced by the teaching staff teaching this population. After reviewing the characteristics and difficulties, the “cycle of exclusion in education” will be presented as linking the characteristics of the students and the difficulties of the teachers of excluded at-risk youth. The description of the students’ characteristics, teachers’ difficulties, and “cycle of exclusion” will serve as the basis for the argument presented at the beginning of this article that asserts that special training and specialization are needed for the teachers of at-risk youth.

The Public Committee to Examine the Situation of Distressed and At-Risk Children and Adolescents (Schmid, 2006) has established an agreed definition of at-risk children and youth, according to which at-risk children and youth are children and adolescents living in situations that endanger them in their family and their environment, and as a result of these situations their ability to exercise their rights under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC) has been impaired in the following areas: the right to survival, life, and healthy development, the right to family ties, the right to education, learning, and acquiring skills, the right to welfare and emotional health, the right to belonging and social participation, protection from others and protection from their own behaviors that might endanger them (Schmid, 2006).

There are several optional frameworks that integrate students who have dropped out of the mainstream frameworks:

“MAHAT” – Technology Education Center. Designed for students who have difficulties to persevere in comprehensive or other schools in the fields of learning, conduct, and regular attendance, these schools combine academic learning with vocational learning. The uniqueness of these schools is in their size (between 150 and 250 students), as well as in the number of students per classroom (between 13 and 20 students). The centers cater to those students who need closer supervision and a more focused view of their individual needs. Setting the personal and class goals is done through strengthening self-belief, self-efficacy, the experiences of success, and a sense of belonging and meaningfulness in the school.

“Miftan” – The Youth Employment Project is an Israeli educational-therapeutic framework for the rehabilitation of detached youth, operated by the Youth Rehabilitation Service in the Ministry of Social Affairs and Social Services, through the local authorities and in cooperation with the Ministry of Education The “Miftanim” schools are schools with an educational-therapeutic orientation for youth in grades 8-12, who dropped out of formal educational frameworks.

Boarding schools – Some of which are academic and some are therapeutic for at-risk youth in which students receive vocational training.

Youth Advancement: “HILA” operates as a “safety net” provided by the Ministry of Education in the local authorities for the care of children and adolescents who have overtly dropped out of the formal educational frameworks. HILA is a unique recognized educational framework that works to educate and complete the education of these adolescents. The program is aimed at implementing the Compulsory and Free Education Law to the end of 12 years of study and assists youth in the transition to an active and contributing adult life in society (Ministry of Education, n.d.).

Vocational schools of the Ministry of Economy, in which pupils can work and receive a salary during grades 11 and 12.

At-risk youth share numerous personality and environmental characteristics. The various factors that affect risk in youth schooling are heavily interlinked. There are several characteristics common to excluded at-risk youth, each of which affects the student’s ability to cope with the challenges of learning and social integration in school. Some of these difficulties are directly related to their family background: Many of them come from large families, most of the families suffer from chronic problems, parental dysfunctions, delinquency, crisis situations, changes in family structure, unemployment and economic difficulties (Cohen-Navot, Ellenbogen-Frankovits, & Reinfeld, 2001).

Main Body

Behavioural and social characteristics of at-risk youth are expressed in the following difficulties: Difficulty integrating into normative social frameworks, feelings of loneliness, difficulties in self-control and delayed gratification, behavioural problems, ostracism and social rejection, a tendency toward aggression, violence, and a reluctant attitude towards authoritarian figures. In more complex cases the emotional coping is expressed in the development of eating disorders, depression and suicide attempts (Cohen-Navot et al., 2001).

The emotional characteristics of at-risk students include feelings of helplessness, low self-confidence, and signs of anti-social behaviour. At-risk students are characterized by existential anxiety that sometimes makes it difficult for them to connect to meaningful and valuable learning. The difficulty in promoting them from the status of at-risk students who are at the margins of society to students with normative functioning stems from the complexity of the phenomenon of risk and the existential anxiety with which they live. These students prefer to engage in things that distract them from their anxiety and avoid the risks involved in connecting or progressing in their studies (Lahav, 2014).

In the education system, it is possible to identify distressed and at-risk children and youth who are struggling to adapt to the demands of the regular system, despite the fact that they have a normal educational potential. They are characterized by low scholastic achievement and an experience of academic failure that accompanies them throughout their lifetime. According to the research report of the Brookdale Institute (Cohen-Navot et al., 2001), there are similar external manifestations that describe at-risk students: covert dropout, students who are not available for meaningful learning, low achievement, students in social isolation, behavioural problems, difficulty accepting the authority of adults and difficulty in receiving assistance from them, and a general difficulty in adapting to framework rules.

In a summary report of the Committee for Children and At-risk youth, HarNoy (2005) defined educational risk situations as reflected in low achievement, lack of basic reading and writing skills, transitions between frameworks, disciplinary and adjustment problems, learning disabilities, lack of interest in studies and frequent absences to complete disengagement. According to Mor (2003), the main characteristic of at-risk students is covert dropout, that reflects an ongoing state of low scholastic performance, which endangers the continuation of the student’s studies in the educational framework, and is characterized by irregular attendance that is part of the dropout process. The student may attend school but do not study and engage in learning, a situation that increases the educational gaps compared to their peers. Cohen-Navot and colleagues (2001) found that these adolescents leave school due to negative and unsuccessful experiences within it. In many cases the school fails to adapt its functioning to the children’s needs, does not set a significant goal for their advancement and thus contributes to their dropout. In addition, the system does not have sufficient awareness of the fact that the school must change its work patterns to suit the needs of the population.

At-risk students often express a negative attitude towards the educational framework, feel distant, negatively evaluate the teachers’ attitude toward them, and feel lonely and alienated. Accordingly, it was found that there is a positive relationship between the adolescents’ attitudes towards the school and their scholastic achievements. The greater the sense of belonging to the educational framework, the greater the level of adaptation, which is expressed in positive attitudes towards the educational framework and its staff, this in turn generates motivation, improvement of scholastic achievements, and desirable and normative behaviour (Trommer, Bar Zohar, & Kfir, 2007).

The teaching staff in schools that cater to at-risk students is composed of both teachers who completed their teacher training in teacher training institutions and professionals who did not study in teacher training colleges, either with or without prior teaching experience. They are the ones who have direct daily interaction with the students and therefore are have the crucial importance in identifying signs that may indicate risk and distress. The characteristics described above entail the coping of teachers of excluded at-risk youth with many difficulties such as students’ irregular attendance, lack of desire to learn resulting in learning gaps and the need for a different pedagogy, lack of cooperation from the student’s family, difficulties in social-emotional conduct, rejection of teachers’ authority and violent behaviour. The teachers’ coping with these difficulties is detrimental to their professional- and self-confidence as well as their self-efficacy.

Damage to the Teacher’s Professional- and Self-Confidence

In recent years, the teacher’s role in Israel has been supplemented with pedagogical and educational requirements that hinder their work and might harm their professional- and self-confidence, in that they create a psychological and physical burden for the teacher, which may cause them to think that they are incapable of advancing their students to an appropriate degree and harm their sense of self-efficacy (Lev & Rich, 1999). Studies show that generally, and somewhat paradoxically, teachers in the educational reality in Israel who teach and educate this population are often marginalized in the school and do not garner any prestige, despite the fact that their work is difficult and requires many unique skills. These teachers, much like their students, experience and accumulate failures over time, and develop a sense of low self-efficacy and high burnout. As a result, professionals develop professional perceptions and behaviors that are influenced by the emotional processes they undergo. The entry into the systems that deal with at-risk youth confronts teachers with a turbulent and tormented emotional world that characterizes the organization and the individuals working within it. The work, along with a sense of failure, repeatedly confronts educators with feelings of incompetence stemming from the inability to see themselves as good professionals. They suffer from a sense of disrespect from others who are significant in their professional environment (students, supervisors, parents, management, other professionals in the organization, etc.). In such a process, they develop hindering patterns that, in the absence of support, give rise to a strong feeling of incompetence (Razer, Warshofsky, & Bar-Sade, 2006).

Self-Efficacy

In order to understand the complexity of the sense of self-efficacy among teachers of at-risk youth, the term “self-efficacy”, that stems from the social-cognitive approach and its definition was formulated by Bandura in 1977 as the individual’s belief that they can organize and implement the required actions to achieve the desired outcomes. That is, when teachers develop professionally and deepen their knowledge, they expand their repertoire of professional skills and, as a result, their sense of self-efficacy increases (Henson, 2001; Swackhamer, Koellner, Basile& Kimbrough, 2009). Studies have shown that teachers with a sense of high self-efficacy believe that they positively affect student outcomes, implement high quality professional practices and adopt novel approaches and teaching methods that encourage autonomy and independence among their students. In addition, they demonstrate strong work ethic and feel satisfaction with their work, which helps them maintain their positive influence on their students’ achievements (Khurshid, Qasmi, & Ashraf, 2012; Swackhamer et al., 2009;). Furthermore, self-efficacy consists of beliefs, their sources and influences, processes in which they exist, and ways in which these beliefs are created and strengthened. In other words, if a person has a belief that they will succeed in a particular task, they are more likely to perform it, and avoid a task they do not believe they will succeed in.

Teachers are the most important component of the education system, but they are especially important in education with excluded at-risk youth. Therefore, if they were to have professional confidence and a sense of self-efficacy their work will be more meaningful and effective; hence the importance of discussing this issue in the context of teaching at-risk youth (Henson, 2001; Khurshid et al., 2012).

Teachers with a high sense of self-efficacy feel that they have the ability to make a difference in the lives of their students and they demonstrate this belief in their teaching. It was found that these teachers are very satisfied with their work, demonstrate great commitment and are less absent from the school. In addition, they demonstrate determination to succeed in difficult situations, dare to implement innovative teaching methods, and their students are highly motivated. It is important to note that in the theoretical literature, self-efficacy is not a stable trait so in order to maintain it, it is necessary that the teacher participate in professional development courses and interventions, in which the teacher develops their skills, creative thinking, and monitors their professionalism (Henson, 2001).

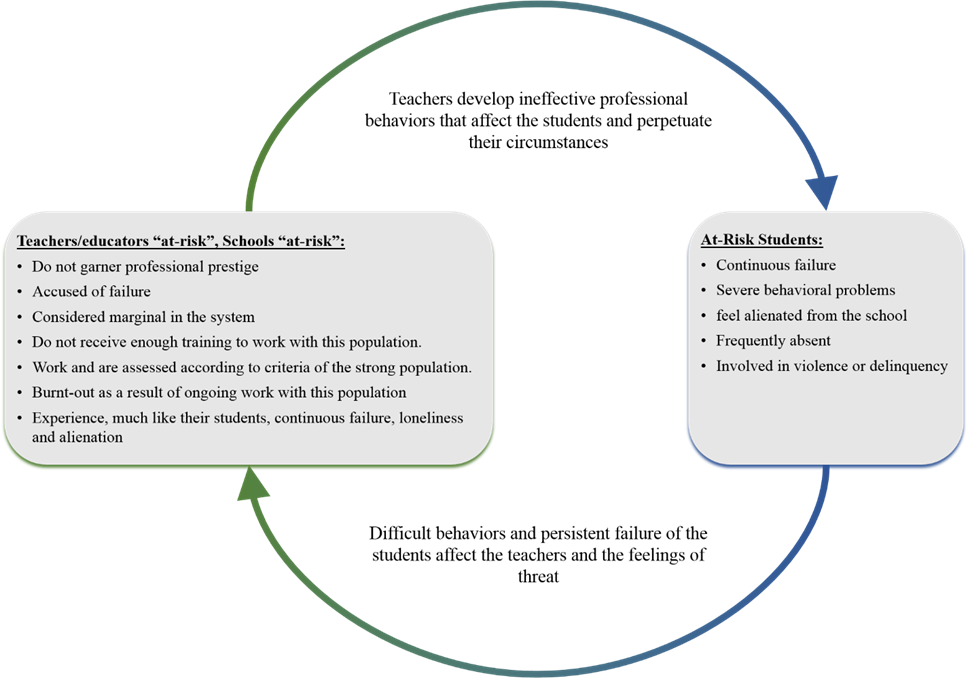

The “cycle of exclusion in education” is a phenomenon that relates to the mutual influence between the distress of the student population and its social exclusion and the distress of the professional staff who are supposed to cater to their needs and help them break out of the cycle of failure. The cycle of exclusion as described by Razer (2009) is depicted in Figure

Figure

Teacher Training

The training of education and teaching staff in the education system is carried out both within initial teacher training and during the course of their work. Some of the colleges offer their students courses dealing with the identification of at-risk children, abused and neglected children, and methods of working with them. Courses of this type are not compulsory in all colleges. The prospective teaching staff also receive training in this topic during the pedagogical training prior to their accreditation. The Ministry of Education has published detailed training materials for use by professionals in the psychological-counselling service in order to provide guidance to the education and teaching staff, but it does not contain detailed information regarding the use of these publications in the education system (Weissblei, 2012). Hence, a teacher who does not receive proper training for working with at-risk youth develops inefficient professional behaviour that affects the student and perpetuates their situation, which makes it difficult for the student to leave the cycle in which they are situated.

The education system in Israel operates according to a policy cantered on academic achievements and naturally, revolves around the stronger student groups. However, in an attempt to prevent social exclusion, teachers are engaged in narrowing the gaps in achievements of the weaker groups, with the approach of placing utmost importance on immediate and measurable outcomes (Razer,Warshofsky, & Bar-Sade, 2011).

There are many dedicated educators who invest efforts to assist under-achieving students, but they lack the professional training and emotional support required in the unique and difficult work with this population. As a result, teachers of at-risk youth experience and accumulate failures and a low sense of self-efficacy in their professional community.

The process of specializing in working with youth in risk processes begins with making a conscious choice of establishing contact and non-abandonment, as well as a thorough and systematic introspection of the feelings, thoughts, and behaviours they experience in their interactions with students and their parents. It is very important for these educators to realize that they will succeed in the task if they learn to share their difficulties and receive assistance in order to maintain their ability to meet the demands of the task (Mor, 1997, Razer et al., 2011). Various studies have found that training and support provide means to increase the sense of satisfaction and commitment among teachers (Fore, Martin, & Bender, 2002)

In addition to support, teachers should deepen their knowledge of children’s psychological development, acquire effective communication skills, develop skills for creating a coalition with parents, and develop skills for teamwork, as well as mastery of their field of knowledge and developing innovative technological skills (Cohen-Navot et al., 2001).

Methodology

A scientific review of the relevant literature was performed.

Conclusion

This article showed that teachers engaged in educating and teaching at-risk youth are often found at risk situations, similar to those of their students. The teachers who come into daily contact with at-risk youth experience, much like their students, feelings of continuous failure, alienation and loneliness. As a result, the school staff is unable to carry out their duties and advance their students.

The concept of “cycle of exclusion in education” refers to a phenomenon in which there is a mutual influence between the sense of exclusion, alienation, loneliness and failing to satisfy the needs of students, and the teachers’ distress characteristics. The continuous coping with the distress, the failure and the behavioural problems of at-risk youth, without proper professional training and support, harms educators on the level of professional identity and on the personal level, both physically and emotionally. The distress experienced by teachers in the cycle of exclusion causes them to develop professional perceptions and behaviours that are not effective for the target population, and sometimes, instead of contributing to positive change, result in opposite outcomes. The professional staff is the one that is supposed to cater to these students and help them break out of the cycle of failure, but both sides are in need and their needs are not met (Razer et al., 2011).

It is important to note that in their private lives, most of these teachers are in the mainstream of society and the sense of exclusion belongs to their professional life in school. Paradoxically, these teachers have the ability to break out of the cycle of failure and bring about change, first in their own lives and second in their students’ lives. This article showed that in order to break free from the cycle of distress, there is a need for the development and professionalization of educators working with excluded at-risk youth, aside from the requirement that these teachers possess multidisciplinary knowledge and many unique skills..

References

- Cohen-Navot, M., Ellenbogen-Frankovits, S., &Reinfeld, T. (2001). School dropouts and school disengagement. Jerusalem: JDC-Brookdale.

- Fore, C., Martin, C., & Bender, W. N. (2002). Teacher burnout in special education: The causes and the recommended solutions. The High School Journal, 86(1), 36-44.

- HarNoy, S. (2005). National Task Force for the Advancement of Education Israel: National Program. From Exclusion to Inclusion, 13, 150-179.(In Hebrew).

- Henson, R. K. (2001). Teacher self-efficacy: Substantive implications and measurement dilemmas. Annual Meeting of the Educational Research Exchange, College Station, TX.

- Khurshid, F., Qasmi, F. N., & Ashraf, N. (2012).The relationship between teachers’ self-efficacy and their perceived job performance.Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(10), 204-223.

- Lahav, C. (2014). A profile of disconnected youth in Israel. In E. Gruper, & S. Romy (Eds.), Children and adolescents at risk in Israel (Vol. I): Overview of the Field and Core Issues. Tel-Aviv: Mofet Institute. (In Hebrew).

- Lev, S., & Rich, Y. (1999).The meaning and measurement of teacher efficacy and counselors’ contribution to its enhancement. IyunimBahinuch, 4(1), 87-117. (In Hebrew).

- Ministry of Education (n.d.).Advancement of Youth at Risk Section. Available from: http://cms.education.gov.il/EducationCMS/Units/YeledNoarBesikun/machlakot/KidumNoar/English.htm

- Mor, F. (1997). An educational Psycho-social intervention for youth at-risk on the verge of dropout in an educational system. Jerusalem: JDC Israel Ashalim Publishing House. (In Hebrew).

- Mor, F. (2003). A study of psycho-educational intervention for effective educational work with underachieving youth at-risk in the education system (Doctoral dissertation). University of Sussex, United Kingdom

- Razer, M. (2009). Non- abandonment: A dynamic model of school-based professional development for teachers of “at risk” and “excluded” students. Mifgash: Journal of Social-Educational Work, 29.

- Razer, M., Warshofsky, B., & Bar-Sade, A. (2006).Being a teacher in an environment of distress and social exclusion. Jerusalem: JDC Israel Ashalim Publishing House. (In Hebrew).

- Razer, M., Warshofsky, B., & Bar-Sade.A. (2011).A different Connection: Shaping a new school culture in work with excluded and at-risk students. Jerusalem: JDC Israel Ashalim. (in Hebrew).

- Schmid, H. (2006). Account of the Public Commission for Disadvantaged and At-Risk Children and Youth. Jerusalem: Prime Minister’s Office. (In Hebrew).

- Swackhamer, L. E., Koellner, K., Basile, C., & Kimbrough, D. (2009).Increasing the self-efficacy of inservice teachers through content knowledge. Teacher Education Quarterly, 36(2), 63-78.

- Trommer, M., Bar Zohar, Y., &Kfir, D. (2007). Coping with covert dropout among at risk students in schools. From Exclusion to Inclusion, 14, 63-93. (In Hebrew).

- Weissblei, E. (2012). The role of the education system in identifying and detecting children at risk (Report for the Education, Culture and Sport Committee). Jerusalem: The Knesset Research and Information Center (In Hebrew).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Bavli, K., & Chis, V. (2019). Training And Professional Development For Teachers Of Socially Excluded At-Risk Youth. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 228-235). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.29