Abstract

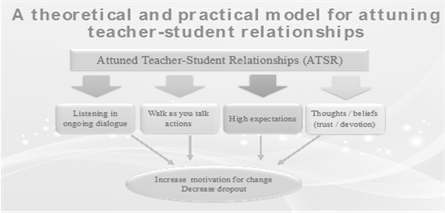

School dropout is a worrying phenomenon, occurring in high school, mainly at 'second chance' high schools, where students are defined as being at risk. The reasons for this, as revealed in many studies, depend on students, traits they bring with them to school, their family status, their learning difficulties, their attention deficit disorder as well as their behavioral problems, and their learning skills in generally. Those studies pointed out those reasons to be the important, for at risk students, dropping out school. The current mixed-methods case study undertaken at a 'second chance' high school, examined the teacher-student relationships as a significant tool attuned to reduce dropout rates and increase students' efficacy and motivation. 101 students, 15 teachers and 9 graduates participated. The research tools were questionnaires, semi-structured in-depth interviews and classroom observations. The main research findings: Teacher-student relationships attuned to preventing students ‘dropout and empowering students constitute a significant factor; Teachers do not consider themselves a significant factor in the dropout process; Teachers struggle to create attuned teacher-student relationships; A gap was identified between teachers’ educational “credo” and their work in practice. The research proposes a model (ATSR), emphasizing principles on which attuned teacher-student relationships can be built: listening in ongoing dialogue, walk as you talk actions, high expectations, the stuffs ‘thoughts/beliefs. An accompanying program will be proposed to assimilate the model.

Keywords: Teacher-student relationships'second chance' high schooldrop-outat risk students

Introduction

The world of content shared between teachers and students on a daily and hourly basis includes day-to-day matters, general and personal information, infinite interactions that constitute a learning platform relating to everything in life.

If this is the point of origin of the educational process, then it is worthwhile paying attention to these interactions, their importance, who conducts them and how they are conducted.

Against this background, students' dropout, which constitutes one of the greatest problems in the education systems in many countries, is perceived as a possible direct reaction to this interaction between teachers and students, who vote with their feet in the context of the education system in which they find themselves. There are many reasons for students’ dropout according to research literature (Alexander, Entwisle, & Horsey, 1997; Frank, 1990; Sasson-Peretz, 1998; Chis, 2014).

Adler (1980), Cairns and Neckerman (1989), Cohen and De Bettencourt (1991), Finn (1987), Lahav (1999), Wolman, Bruininks and Thurlow (1989) and others mainly emphasized the basic traits with which students arrive at school. Later studies have also dealt with quality relationships between teachers and students (Blum, 2005; Capern & Hammond, 2014; Gilles, 2011; Hattie, 2009; Klem & Connell, 2004; Pianta, 1999).

This study sought to shed light on the significant relationship between teachers and students and its effect on dropout rates or alternatively, on students’ perseverance and changes they can make, when teacher-student relationships constitute a tool in teachers’ hands for this purpose.

The model proposed by the research, derives from the research results and the needs teachers and students identified. The model tries to equip teachers with tools to cope with students, and particularly when referring to at-risk youth.

Problem Statement

Studies dealing with at-risk at high school students, as well as teacher-student relationships, emphasize their importance and meaning for such students. Emphases refer mainly to listening to the students' needs, improving their feelings, improving relationships as a condition and positive platform for advancing students (and sometimes even referring to teachers' feelings, or the satisfaction they derive from working with students). Researchers refer to 'quality relationships' (Blum, 2005; Capern, 2014; Hattie, 2009; Klem & Connell, 2004; Pianta, 1999).

Tuning teacher-student relationships. To clarify 'tuning relationships' - teacher-student relationships are not merely friendly, but they have a direction, they are supposed to be accurately attuned to the needs of students. Regarding the metaphor, it is taken from the world of music to emphasize that as in music: the sound has to be exact, so too with teacher-student relationships. The tones of the relationships must be accurate, especially with students at-risk. Here nothing can be off-key, every inaccuracy is crucial for such students.

The gap in knowledge that led to this research, was that no studies were found that are linked to second chance schools, teacher-student relationships and dropout.

This study which links teacher-student relationships to dropout and motivation for change, examined this in-depth and focused on relationships in these contexts with students at a second chance school. This accuracy can serve as the basis for a model that will serve teachers, dealing with youth at-risk, and who are supposed to lead their students to make a change to their learning circumstances.

Research Questions

What do teachers do to attune teacher-student relationships to decrease students' dropout tendencies and increase motivation for change at the studied second chance high school? How do teacher-student relationships affect students' motivation to change and their dropout tendencies at the studied second chance high school? What are teachers' views on education and credo at the studied second chance school?

Hypotheses: (1) There will be a negative correlation between teacher-student relationships and dropout tendencies at the studied second chance high school. (2) There will be a positive correlation between teacher-student relationships and the students' level of motivation for change at the studied second chance high school.

Purpose of the Study

The research sought to identify what second chance school teachers do to attune teacher-student relationships in order to decrease students' dropout tendencies and increase their motivation for change, and to examine how teacher-student relationships affect students' motivation for change and their dropout tendencies at a second chance high school.

Research Methods

Research strategy:

Case study: Because of the nature of the research field, it was important, that the voice of individuals be heard. Nevertheless, it was also important to examine and refer to numerical data. Hence the chosen research method had, on the one hand, to bring the uniqueness of understanding and exposing knowledge found in the hands of individuals taken in context, as noted by Flyvbjerg (2006), in his reference to case studies. Thus, it was important to draw out all texts comprehensively from the research population. Beveridge (1951) added that in case studies, there is an authentic observation that brings out and emphasized precisely the small details, that protects the research from forgery. These two aspects allow one to identify and illuminate pieces of information important to the research. On the other hand, it is important to use other methodologies, to complete the information. Mixed- methods completes the information and bring the necessary synergy to holistic research (Bryman & Becker, 2012). Therefore, this study is a case study carried out using a mixed-methods.

Population, sampling method and research tools:

The research was conducted at a second chance high school in the centre of a large city, with 130 students from 9th – 12th grade. The research population was selected as convenience samples. 101 students from all age groups studying at the school responded to a quantitative questionnaire, Wubbles’ (1993) “Questionnaire on Teacher Interaction” (QTI), 16 teachers teaching at the school and 9 previous students were interviewed using semi-structured interviews, an in-depth tool enabling interviewers to understand more comprehensively (Fontana& Frey, 2000). Classroom observations were conducted according to Shkedi’s (2001) observation principles and during visits to observe classes, led to genuine picture, which corresponded to interviews and the information in the qualitative research.

Findings

It is important to emphasize that many findings emerged, but for the focus of this article, only findings relating mainly to teachers’, students’ and graduates' attitudes regarding student dropout and teacher-student relationships will be addressed. An important finding, referred to teachers’ training to build empowering teacher-student relationships as well as a description of the practical situation in classes, during lessons.

One of the important findings, emerging from interviews with teachers, was their insight that student dropout derives mainly from their socio-economic status, an absence of fixed learning habits, and therefore they are used to fail, as well as a lack of motivation. They even emphasized that teacher-student relationships had a small role in the reasons for students dropping out of their studies. Thus, their responsibility is minimal and partial.

In reference to the question of teacher-student relationships, teachers clarified that they lack tools to establish empowering and influential teacher-student relationships. In contrast, with regard to the matter of teacher-student relationships and dropout rates, it emerged from interviews with graduate students that these relationships are the most significant in the student dropout process.

Classroom observations revealed that teachers do, however, try to establish positive interactions with students, to the best of their understanding and ability, if and when lessons are conducted without disturbances. Teachers relate to students using direct language, students who are willing to be partners in lessons function and teachers relate to them, while with other students, alienated from lessons, teachers turn to them with words of encouragement. If this has no effect, teachers ignore them. Teachers also chose to refrain from dealing with discipline problems, as long as they were not a significant factor disturbing lesson conduct (Figure

The proposed model and its components, first, appear to be obvious. This is because its key components, such as “walk as you talk”, “establish ongoing dialogue as part of the process”, “high expectations”, and “thinking about and believing students and the process build trust and commitment”. Indeed, teacher-student relationship are almost automatically formed. Teachers see their students, hour after hour, minute after minute every day. Naturally, relationships are established, characterized by emotions, beliefs and thoughts. However, this model seeks to direct this relationship to an objective, which will answer the needs of students studying at a second chance school. The model was derived from the research findings, emphasizing the correlation between teacher-student relationships and dropout rates of at-risk youths studying in a second chance school. It appeared that there was a need to clarify, through the work of teachers, most of whom noted, on the one hand, that they do not possess the tools to establish empowering relationships with students, and on the other, most teachers emphasized that their relationships with pupils is a significant force in the whole process of them being at school.If so, does the significant relationship include responsibility for dropout? As for this matter, it is important to remember that the findings indicate teachers' reservations regarding their responsibility for dropout, because according to their understanding, the reasons for dropout are mainly students, their families and their learning history. Hence, teachers sway between conflicting feelings. On the one hand, the feeling that their relationship is significant and that their responsibility for dropout is minimal. On the other hand, they do not have the tools to create meaningful and empowering relationships with students. Such a catch in which the teachers find themselves may frustrate the teacher's work.

This is how the need for a model was created as a tool or teachers to work and establish that effective, influential and empowering relationship with students.

Model principles:

(1) Listening in ongoing dialogue were the key words that led to this principle. Where there is listening, there is control. In conversations led by the principle of ongoing dialogue, the lead’s control is stronger and more emphasized. The accompanying values in these circumstances, among students is the sense that there is someone they can rely on. Students will enter dialogue with confidence that they are being listened to, that they have the opportunity to express themselves, without judgment, and therefore their expression will be authentic and fluent, without fear. Hence the students have a sense that everything is open to discussion, that they have the power to change things through conversation. These feelings are important precisely in conversation where teachers seek to influence or modify students’ behaviour. It is important to refer to listening as a foundation to any dialogue that should occur all the time.

(2) Walk as you talk. From the research findings, and mainly in interviews with graduates, it emerged that teachers’ credibility was in doubt, because they “did not keep their word, and even after a conversation, would relay everything to the principal”, and there were even those who went further and emphasized that generally “teachers lie”. This feeling, which accompanies students and their relationships with teachers, are indeed subjective, but nonetheless, such feelings, which exists and are stated openly, are an obstacle to developing empowering, targeted relationships. Credibility is a requirement noted by graduates, when they were asked to refer to their relationships with teachers. Thus, in building relationships with students, it is important to consider this component of building credibility and exploring what is the best way of creating and applying credibility and trust in relationships between teachers and students. Trust between countries, between people, between parents and children, and also between teachers and students, is established in simple steps that insist on accurate matching between words and deeds. Teachers must lead this process, and thus they, on the one hand establish important behavioural norms for the present and future to come, and on the other hand implement a key component that moulds their relationships with students.

(3) High expectations: this principle is important both in establishing relationships with students and establishing motivation to change. Research literature refers greatly to this topic either directly or indirectly (Bandura, 1977; Deci & Ryan, 1991, 1985; Deci Ryan, & Williams, 1996; Ryan, 1995) and other researchers, with reference to motivation and developing self-efficacy, spoke on the one hand about beliefs and desires people develop, over a long period process, and these build motivation and capability. On the other hand, they spoke about challenge. People are social creatures and their lives, among others, are comparative. A student says: if he can, so can I (Bandura & Barab, 1973). This is comparative thinking that has a constructive value. Additionally, the challenge teachers set for students, and thus build their belief in themselves and considering themselves as students (Baron, Kaufman, & Stauber, 1969; Kaufman, Baron, & Kopp, 1966). With at risk youth, teachers who set their students challenges and have high expectations from them, rebuild how students assess themselves. For this assessment to lead to change, students' needs teachers’ support and supervision. The formation is, it is possible, you are not alone, you can, we are in this together. In this way teachers connect students to the process at school and help them to persevere and not drop out.

(4) Thoughts/beliefs/trust/commitment - this principal complements the previous principle, and it directs both teachers and students. If the previous principle emphasizes teachers’ commitment to build up students’ belief in themselves, then this principle emphasizes teachers’ beliefs and thoughts about students. It is important to remember that students, defined as at-risk, experience failure most their school lives. Their self-image is built accordingly regarding their studies at school, and thus regarding their abilities to learn or persevere. Teachers exposed to at risk youth, naturally, will have preconceptions about such youth, mainly attributes such as: ‘difficult’ youth, with attention and concentration problems, without learning habits, behavioural problems and more, some of which are surely correct. These are teachers’ starting conditions when dealing with these students. Coping on the on hand with students and their difficulties, teaching, reaching achievements and perseverance with them, supporting them, being meaningful, influential and attuned to them. On the other hand, preconceptions sometimes lead to actions, mainly in hours of trouble. Teachers' skills are meant to be professional to the utmost, so that on the one hand they are aware of future difficulties in their work with youth (One must emphasize that this does not mean teachers should ignore these attributes. On the contrary, they must know about them beforehand), but on the other hand, not to let stigmatized thoughts control them. One of the ways of coping with stigmatized thoughts is to go over building trust with and commitment to students. Trust and commitment, two entwined values. When these become the foundations on which teacher-student relationships are built, there is no place for stigmatized thoughts. They dissipate, whereas trust and commitment become the dominant force in relationships.

6.2

Conclusion

What is the connection between reducing dropout rates and the proposed model as a remedy for this plague?

To answer this question, we must return to the needs and attributes of at-risk youth. The main problems arising whether in interviews with students or teachers, is how students cope, over the years, with the education system and its representatives, lack of trust, absence of listening and stigmatized attitudes. These are the basic and real reasons why these students drop out.

Reasons for students dropping out are many, and often do not depend on students themselves, such as low socio-economic status and family problems. However, the other reasons for dropout develop over time (such as inability to adapt, absence of learning habits, learning difficulties, attention and concentration problems, behavioural problems) through students’ friction with the system. Thus, it is possible, that if the reasons are caused by this friction, one can deal with them and reduce them using the proposed model.

Teachers, who are exposed to students for so many hours during the day, are the main representatives of the education system, and most of the weight and responsibility of coping with students falls to them. The proposed model can give them an important tool to deal with the issue of reducing dropout rates.

Naturally, teachers must be trained in this skill, which combines the model’s principles. The research also proposed a training program for new and veteran teachers. The main subjects of the program are providing up to date knowledge and learning how to establish meaningful communication with students, through team work, practical exercise and supervision. The training program is still in its initial phase and requires testing and follow-up.

Many teachers spoke about ‘love’ when referring to teacher-student relationships and dropout. In the proposed model, this is not a core value. What led to this was the thought that the ‘love’ mentioned by teachers does not have a clear definition, what does it refer to, what is the framework of this ‘love’, does it mean affection? Does it mean support? On the matter of ‘love’, the space for interpretation is huge. Therefore, this value was not introduced into the model. Nonetheless, the ‘love’ for students, in all its interpretations, is produced anyway, through the relationships structured on the model.

References

- Adler, H. (1980). Report of the committee for educational alternatives for youths outside schooling frameworks. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education (In Hebrew)

- Alexander, K. L.; Entwisle D. R.; Horsey C. S. (1997). From first grade forward: early foundations of high school dropout. Sociology of Education 70, 87-107.

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change. Psychological Review 84, (2), 191-215. Stanford University.

- Bandura, A., & Barab, P. G. (1973). Processes governing disinhibitory effects through symbolic modeling. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 82, 1-9.

- Baron, A., Kaufman, A., Stauber, K. A. (1969(. Effects of instructions and reinforcement-feedback on human operant behavior maintained by fixed-interval reinforcement. Journal of the Experimental Analysis of Behavior, 12, 701-712.

- Bartolome, L. I. (1994). Beyond the methods fetish: toward a humanizing pedagogy. Harvard Educational Review 64, 173 – 194.

- Beveridge, W. I. B. (1951). The art of scientific investigation. London: William Heinemann.

- Blum, R. (2005). A case for school connectedness. Educational Leadership, 62(7), 16-20.

- Bryman, A. Becker. S., Ferguson, H. (2012). Research for social policy and social work. Themes, methods and approaches. Bristol: University of Bristol: Policy Press.

- Cairns, R. B.; Cairns, B. D.; Neckerman, H. J. (1989). Early School Dropout: Configurations and Determinants. Child Development 60, 1437 – 1452.

- Capern, T., & Hammond, L. (2014). Establishing positive relationships with secondary gifted students and students with emotional/behavioural disorders: giving these diverse learners what they need. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(4). DOI:

- Chis, O., (2014). Outcomes of an initial teacher training program of disadvantaged groups in primary and preschool education, 2nd International Conference on Globalization, Intercultural Dialogue and National Identity, Tirgu Mures, May 29-30, 2014, Conference volume: Globalization and intercultural dialogue: multidisciplinary perspectives - education sciences pages: 268-278 .

- Cohen, S. B; De Bettencourt, I. V. (1991). Dropout: intervening with the reluctant learner. Intervention in School and Clinic, 26, 263-271.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1991). A motivational approach to self: Integration in personality. In R. Dienstbier (Ed.), Nebraska Symposkum on Motivation, 1990 (pp. 237-288). Lincoln, NB: University of Nebraska Press.

- Deci, E. L., Ryan, R. M., & Williams, G. C. (1996). Need satisfaction and the self-regulation of learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 8, 165-183.

- Finn, C. E. (1987). The high school dropout puzzle. Public Interest, 87, 3-22.

- Flyvbjerg, B. (2006). Five misunderstandings about case-study research. Qualitative Inquiry, Vol. 12, No. 2, 219-245.

- Fontana, A. & Frey J.H. (2000). The interview: From structured questions to negotiated text. In N.K. Denzin & Y.S. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (Second Edition, pp. 645-670). London: Sage Publication.

- Frank, R. J. 1990. High School Dropouts: A New Look at Family Variables. Social Work in Education 13, 34-47.

- Gillborn, D. (1997). Ethnicity and educational performance in the United Kingdom: racism, ethnicity, and variability in achievement. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 28, 375-393.

- Giles, D.L (2011). Relationships Always Matter: Findings from a Phenomenological Research Inquiry. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 36, 80.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible Learning: A Synthesis of Over 800 Meta-Analyses Relating to Achievement. New York: Routledge.

- Kaufman, A., Baron, A., & Kopp, E. (1996).Some effects of instructions on human operant behavior. Psychonomic Monograph Supplements, 1, 243-250.

- Klem, A., & Connell, J. (2004). Relationships matter: linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health, 74(7), 262-273 DOI:

- Lahav, H. (1999). Youths at the margins of society: the phenomenon and ways of coping. policy of treating youth at risk and detached youths in israel: target population, aims, action, principles and strategies. Jerusalem, Israel: Ministry of Education, Culture and Sport (In Hebrew).

- Pianta, R. C. (1999). Enhancing relationships between children and teachers. Washington, D.C: American Psychological Association. DOI:

- Ryan, R. M. (1995). Psychological needs and the facilitation of integrative processes. Journal of Personality, 63, 397-428.

- Sasson-Peretz, V. (1998). Examining the variables: self-image, academic achievements, social orientation and locus of control in a unique framework for dissociated youths. MA thesis Bar-Ilan University.

- Shkedi, A. (2001). Studying culturally valued texts: teachers’ conception vs. Students’ conception. Teaching and Teacher Education. 17, 333-347.

- Williams, G. C., & Deci, E. L. (1996). Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70, 767-779.

- Wolman, C.; Bruininks, R.; Thurlow, M. L. (1989. Dropouts and dropout programs: implications for special education. remedial and special Education 10, 6-21.

- Wubbels, T. (1993). Teacher-student relationships in science and mathematics classes. What research says to the science and mathematics teacher, 11, Perth: National key center for school science and mathematics, Curtin University of Technology.1978/1995/2010.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Shefi, J. (2019). Attuned Teacher-Student Relationships - Reducing Dropout Rates In A Second Chance School. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 211-219). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.27