Abstract

The research deals with processes and trends in spoken language and cultural language. The aim of this research is to explore the levels of influence of factors involved with the process of choosing words in a language. The pilot findings were: (1) Words updated between 2010 and 2017 semantically transparent to speakers are not spoken in day to day life. (2) Words updated between 2010 and 2017 in the aforementioned fields are rare. Consequently, this research stage turned into a pilot, and an additional research aim was added: Examine the possibility of bridging between the synchronic and diachronic views among language speakers by distinguishing between communication language and cultural language and seeking means of creating a balance between the importance of cultural and communication needs among speakers. In addition, further research tools were developed, which included examining updated words over a longer period of time than had been chosen previously. The corpus of examined words was extended to the 70-year period since the establishment of the state of Israel in 1948 to 2018, the year in which this research was conducted. Developing additional research tools is intended to consolidate the research process, and through them to try to achieve, the research aims and answer its questions.

Keywords: Updated wordssemantic transparencyprevalenceneedcultural language

Introduction

The Hebrew language has sustained the identity and uniqueness of the Jewish people throughout its history. It is the oldest language in the world preserved thanks to a set of external permanent rules, a set of grammatical rules (Ben-Haim, 1953). Ben-Haim added that rules of language will be maintained even with language changes from Biblical Hebrew to spoken Hebrew through the internal language system: in content and meaning (Ben-Haim, 1992 as cited in Birenbaum, 2000).

In contrast, according to Coşeriu (1977), language changes do not exist, but are the creativity of traditional language. This division between a set of external rules and the internal system of language suits the aim of this research: a search for balance between the liberal-normative approach and functional approaches and examining factors involved in introducing new words into a spoke language. Coşeriu (1974) argued that in dialogue there are norms of honesty and tolerance, which include the principle of trust. This norm is naturally found in language speakers, who act accordingly during dialogue.

There is disagreement between liberal linguists who believe that their role ends with observing and describing the processes occurring in spoken language, and the approach of liberal-normative linguists, who believe that they must intervene in these processes.

In this work we will address the question whether it is necessary to intervene in or influence the processes occurring in spoken language so as to examine what factors are involved in assimilated newly introduced words into a language. The researcher, as a Hebrew language teacher, precisely because it is a living, dynamic language in which language changes occur, finds it difficult to describe only the spoken language without preserving cultural treasures expressed in its vocabulary.

Problem Statement

By nature, living language changes all the time. A worrying process is the disappearance of words from speakers’ vocabulary. Words are neglected for a variety of reasons: they fulfil no communication need because the aspect of life to which a word belongs is no longer relevant in the 21st century.

In addition, words are neglected when their foreign equivalent become rooted in spoken language. Also noticeable in the current era, the global-technological era, is the process of narrowed meanings for one meaning, because of the speed and shorthand in speech and writing that characterize this era.

There are different approached addressing the process living language undergo. On the one hand the normative liberal approach that seeks to maintain the existing vocabulary of speakers’ mother-tongue, and in opposition the liberal-functional approach that argues that speakers should be left alone, and their language not interfered with, but only described.

The importance of this research is its integration of normative-liberal and functional-liberal theories, where the guideline is finding a balance between the two. In the research we will seek to find factors involved in choosing newly introduced words in a language from points of view including the following aspects: psycho-linguistic, socio-linguistic, cultural, functional linguistics and semantic-creative linguistics. combining the above theories is the originality of this research.

In this research, the researcher attempted to find a balance on the scale of different theories, and determined research aims as finding this balance using an examination of part of the factors involved in the process of choosing words in spoken Hebrew used on a day-today basis. The words chosen for this study are newly introduced words with lexical creativity.

Research Questions

What is the correlation between understanding the meaning of a renewed word by a speaker and the extent to which it is used in spoken language? What is the frequency of occurrence of words that have been renewed between 2010-2017 in the following categories: politics, family and technology, when the speakers are experts in these areas?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to examine what are the factors that balance the liberal-normative approach and the liberal-functional approach and to examine factors intervening with the introduction of new words into the Hebrew language.

Research Methods

Participants

20 adults completed voluntarilyOpen structured telephone knowledge questionnaire.Constructing an open-structured questionnaire according to the quantitative method, which focused on words newly introduced by the Academy for Hebrew Language between 2010 and 2017. Words with semantic clarity and lexically and structurally creative. The purpose of the questionnaire was to examine what percentage of newly introduced words on a given list were routinely used by Hebrew language speakers.

The research population was based on three demographic criteria seen to be important in producing linguistic differences in Israel: place of birth, age and education. Interviews will be conducted with: natives with and without academic education, Religious or secular, from the center of the country or from the periphery and with a high or low socioeconomic status.

Procedure.

Data collection was conducted using the Mixed Methods Research. The work examines the factors involved in choosing newly introduced words in Hebrew among speakers. This data is likely to be collected through a combination of few research tools. Details of the research tools are shown in the following table

Findings

-

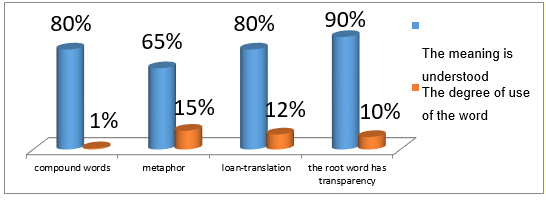

The first finding at the research is thatwords renewed between 2010-2017 that are semantically transparent to speakers are not spoken in daily life (Figure

01 ).

-

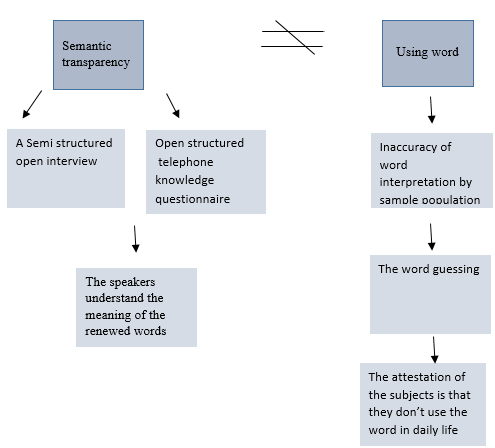

The second finding at the research is that words newly introduced by the Academy between 2010-2017 in the aforementioned fields are rare: A total of 10,000 words from the semantic fields of technology, family and politics were examined. 7,865 words were examined from articles from 2017 in the aforementioned areas and another 2,135 words from oral interviews. These interviews were conducted in 2017 with digital and family personnel and politicians. Likewise, the words chosen for this research are words that were newly introduced between 2007 – 2017 from these areas of life and use in texts is minimal. Details of the Triangulation to validate the findings are shown in the following figure

02 .

Changes following the findings:

As a result of the findings in the research the corpus of examined words will include words dealing with Israeliness to celebrate the 70th anniversary of the establishment of the state of Israel (1948-2018). These findings led to the fact that this initial process could be referred to as a pilot and constituted the first stage of the research.

Stage 2 of the research expanded the range of examined words, research questions, hypotheses and tools were added to existing ones. In this research, we will argue that precisely because of these difficulties it is even more important to preserve vocabulary and their meanings, because it is a part of the culture and identity of the Jewish people. Lacking knowledge of this vocabulary is likely to harm speakers on a number of levels: loss of national vocabulary, loss of sense of belonging, lack basic understanding of words appearing in the press and more, and therefore we moved to stage 2 of the research.

Conclusion

The state of Israel is a country of migrants, and therefore the way to learn the language is difficult. This study must continue because people's language is their identity, through which they get work, integrate into society, and can enjoy theater and poetry thanks to their recognizing changes in language and its style, and most importantly, language is part of people's national identity (Ben Shachar, 2000). Haim Cohen (2014) raised the following questions: In order to speak and write Hebrew, or any other language of any other nation, must people learn the rules and laws of the language? Why bring up a generation of children that will not know their language culture? Are we allowed to teach our language system even if we do not bring all our learning into living speech? (Cohen, 2014).

Gadish (2011) argued that despite natural changes to language, one can see a great degree of stability of Hebrew words in daily use. Many Hebrew words have changed, but most ancient words are not foreign to Hebrew speakers. Every era increases vocabulary in different way but does not forsake its overall legacy. Vocabulary is always open to absorbing from the past, no less than it is open to absorbing from external sources.

Language, from its very nature, changes, and it is not changes that should make us wonder, but precisely continuity and stability. On this matter, Hebrew's route is unique: there is a complete historical unity. Not unity in language, but unity in a pluralistic tradition, depending on a number of language layers simultaneously. This is unity with national consent (Gadish, 2011).

The continuous tension between the language of culture, perceived as written language and natural changes of living language is the matter under consideration in this research. We adopt changes deriving from lexical creativity and foreign influences and understand that error is a principle that inspires language and even reflects social mood at a given time, and therefore there is a need for research to examine the balance between the two. To date (2018), there is absence of works dealing with researching the spoken Hebrew language (Birenbaum, 2000) and examining social processes that influence spoken language (Fruchtman, 2006).

In this research, we will continue the work of linguists dealing with spoken Hebrew research through semi-structured interviews and an open questionnaire. Contribution to knowledge will be expressed through data and its interpretation.

References

- Ben-Haim, Z. (1953). Lashon Atika Be'metziut Hadasha [Ancient Language in a New Reality]. LeshonenuLa'am, 4, 3-5 pp. 42 – 80. Jerusalem: The Secretariat of the Academy of the Hebrew Language (In Hebrew).

- Ben Shachar, R. (2000). She'ifa Tmima: Ledaber Beduiyuk kemo shekotvim [Innocent Ambition: Speaking Exactly Like It's Written]. Ha'aretz,https://www.haaretz.co.il/misc/1.823973.

- Birenbaum, G. (2000). Mekoma Shel Hachvanat Ha'Ivrit Beyameinu [The Place of Language Direction in our Era]. In: Nir, R. (2000). Mehkarim Betikshoret, Bebalshanut Uvehor'at Halashon. [Research in Communication, Linguistics and Teaching Language], pp. 334 – 349. Tel Aviv: Carmel Books (In Hebrew)

- Cohen, H. (2014). Am Velashon – chinuch Vetarbut. [People and Language – Education and Culture]. Lecture in the Academy of the Hebrew Language on the Subject of Teaching Literature and Grammar in Schools. Retrieved from: http://hebrew-Academy.org.il/2014/04/29/%D7%A2%D7%9D-D7%95%D7%9C%D7%A9%D7%95%D7%9F-D7%97%D7%99%D7%A0%D7%95%D7%9A-%D7%95%D7%AA%D7%A8%D7%91%D7%95%D7%AA/

- Coșeriu, E. (1974). "Current Trends Linguistics", volume 1. Linguistics and Adjacent Arts and Sciences, ed. By Thomas A. Sebeok. Paris : Mouton.

- Coșeriu, E. (1977). Linguistic (and other) universals. In: Makkai, A., Becker Makkai, V.,Heilmann, L. (Eds.), Linguistics at the Crossroads, ed. By Liviana. Lake Bluff: Padova & Jupiter Press, Ill, pp. 317–346.

- Fruchtman, M. (2006). Ha'Ivrit Shelanu [Our Hebrew]. HedHauplpanHehadash, 89: pp. 102 – 113 (In Hebrew)

- Gadish, R. (2011). Mi Tzarich Minuah Ivri? [Who Needs Hebrew Terminology]. Lecture in the Academy Conference, RishonLeZion (In Hebrew)

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Hakmon, Y. (2019). Hebrew As A Cultural Language- Spoken Or Broken?. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 171-177). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.22