Abstract

The Jewish Holocaust was the premeditated and systematic murder of more than six million Jews perpetrated by the Nazis under the leadership and vision of their leader, the Fuhrer, Adolph Hitler. This paper presents significant results regarding the influence of certain moderators on the evolution of Israeli high-school students' moral attitudes towards the different strategies employed by Jews to cope with Holocaust and post-Holocaust moral dilemmas through three research stages. The aim of this research was to test whether changes in the participant's moral attitudes during their Holocaust Learning Program was moderated by gender, having Holocaust victims as relatives and participation in the journey to Holocaust memorial sites in Poland.102 male and female participants, students in three Israeli high-schools, responded to Moral Attitudes Questionnaire administered at three timepoints over a period of a one-year Holocaust Learning Program. The results revealed that for the moderator

Keywords: Moral dilemmasmoral attitudesmoderators of change

Introduction

The Second World War (1939-1945) is considered to have been one of the largest, most important and influential historical events for humanity in the twentieth century. Possibly it is also the most terrible of all. During the war and especially between 1941-1945 another horrifying and despicable event occurred - the Holocaust. This phenomenon caused unimaginable suffering to the Jews and other people in Europe involved the premeditated and systematic murder of more than six million Jews and people from other races and nations perpetrated by the Nazis under the leadership and vision of their leader, the Fuhrer, Adolph Hitler (Greif, Weitz, & Machman, 1983; Barley, 2007).

Although the Holocaust ended with the surrender of Nazi Germany on 9th May 1945, it continues to influence and occupy the Jewish people and the State of Israel in various educational, social, and cultural dimensions until today. Without a doubt, it will continue to engage and influence Jews and Israelis for many generations to come (Weitz, 1997). This is the reason why from the early days of the State of Israel, which was established in 1948, the Holocaust was conceived as a fundamental event that defined the nature of Israeli society at different levels. It therefore also had a major influence on the Israeli education system, although its appearance and content in education has altered over the years (Machman, 1998).

The inter-generational trauma of Holocaust is well-described by the following words:

"Among the generations of Holocaust survivors, the children of the survivors, their grandchildren and great-grandchildren, there is an inter-generational transmission of trauma and memory. This trauma has most central significance for each generation and it influences a variety of areas and levels" (Fuchs, 2009, p. 12).

In order to understand the immense influence of the Jewish Holocaust on the Jewish world and especially on the life experience of Israel, to which most of the survivors immigrated, it is important to understand the influence of the Holocaust not only on the survivors but also on the next generation. In April 1945, close to the end of the Second World War, the Jewish population of Israel numbered 500,000 persons (Hadawi, 1970). In the first years after the war, 150,000 Holocaust survivors arrived in the land of Israel so that by the end of 1948, the year in which the state of Israel was established, the Jewish population had risen to 650.000. The increase in the number of Jews was a direct result of the immigration of Jewish Holocaust survivors from Europe (Orbach, 2010). Most of the Jewish residents of the Land of Israel before 1950 had arrived from Europe and they had relatives who had remained in Europe during the war most of them in countries which were occupied by the Nazis. Consequently, by the early 1950s, most of the Jews living in the State of Israel had relatives who had been murdered in the Holocaust or were themselves survivors (Steev, 2002). Second generation descendants of the survivors lived in and grew up in the new Israeli society that was being created. It was very different from the society in which their parents had lived in Europe before the Second World War. For them, the Holocaust was more a sort of myth than the continuous daily reality of the past and present endured by their parents - the generation of the survivors for whom the Holocaust never really ended. This family background shaped and continues to shape the children’s perception of their reality. The difficult events of the Holocaust, which were experienced to a different extent and at different strengths through the medium of their parents, never disappeared and continue to be influential till today (Bar-On, 1994). These influences were explained most succinctly by Gampel (2005):

“The Holocaust changed the meaning of our history, its effects are revealed in the long term, dispersed in space and time like ‘radioactive fallout’; The parents who are Holocaust survivors, their children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren cannot defend their children from their own anxieties” (p. 13).

In Israel the issue of the Holocaust is an important unifying element, held in consensus by all parts of the Jewish society as part of the national ethos (Gottwein, 1998). Israelis experience the subject of the Holocaust in many ways from early childhood, especially in school. From the early days of the State of Israel, the Holocaust was seen as a fundamental event that defined Israeli society at different levels and consequently influenced the Israeli education system, although its appearance and content altered over the years (Machman, 1998). Machman (ibid., p. 687) notes: “It is impossible for the subject of the Holocaust not to be mentioned at one stage or another of the education process”.

Israeli researchers and institutions were the pioneers in the field of Holocaust studies; they were the ones, who provided most of the initial learning materials and those who began to deal with public commemoration and recognition of the Holocaust mainly in the formal education system (Aharonson, 1999). However, in the last 25 years, informal Holocaust studies were created alongside with the formal learning, namely the journeys to visit Holocaust sites in Poland. The journeys, organized by the Ministry of Education, have become a most important component of the Holocaust teaching program and have become a sort of “pilgrimage” for many of Israel’s youth who participate in these journeys (Worgen, 2008).

This paper presents significant results regarding the influence of certain moderators of change on the evolution of participants’ moral attitudes at three points of time over the research period. The research population included high-school students all of them learning about the subject of Holocaust for the matriculation exams. Some of them were boys and some girls, some participated in the journey to Poland and some didn`t and some had family relations who were Holocaust survivors or victims and some didn`t. Therefore, the potential moderators that were chosen were: gender, having a family relative who was a Holocaust victim or survivor and participation in the journey to Poland.

Problem Statement

Previous research did not relate to the issue of Israeli high-school students' attitudes towards the moral dilemmas of the Jewish people in both Holocaust and post-Holocaust eras. Furthermore, as far as could be ascertained there has been no study investigating the connection between the influence of moderators such as gender, having Holocaust victims as relatives and participation in the journey to Holocaust memorial sites in Poland on those attitudes

Research Questions

The research question was: Are there significant influences of the three moderators - gender, having Holocaust victims as relatives and participation in the journey to Holocaust memorial sites in Poland on the students' moral attitudes?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this research was to test whether changes in the participant's moral attitudes during their studies in a Holocaust Learning Program were moderated bythe above-mentioned moderators.

Research Methods

Participants.

The research population included 102 participants - Israeli male and female high school students aged 17-18 from three different high schools in Israel. All of them volunteered to participate in the research. They are members of the third and fourth generation after the Holocaust, but not all have relatives who are Holocaust survivors or victims.

Procedure.

The research took place over a period of two academic years: It began in January 2015 when the students were in the middle of Grade 11and ended in January 2016 when they were in the middle of Grade 12. The research process included measurement of attitudes through the administration of a Moral Attitudes Questionnaire which included 14 Holocaust and Post-Holocaust moral dilemmas at three points in time during this period: Measurement at Point 1 took place when the students were in the middle of Grade 11 in January 2015. At this time, they began their formal learning process for matriculation exams in Jewish Holocaust history and preparation for the journey to visit Holocaust memorial sites in Poland. Measurement at Point 2 took place after the students return from the journey to Poland in September 2015 at the beginning of Grade 12. Measurement at Point 3 took place in January 2016 in the middle of Grade 12. At this time, students completed their matriculation exams on Holocaust studies.

The research tool

The research tool used in this study is a specially developed closed-ended questionnaire investigating the participant's moral attitudes towards Holocaust moral dilemmas. The questionnaire is based on the pioneering work of Kohlberg (1973) and many of his followers for example: Foot (1967) and Graham et al. (2011). It presents seven main moral dilemmas that faced Jews during the Holocaust (1939-1945) and seven more main dilemmas that faced Jews after the Holocaust and up until the present time (1945-2017). These fourteen dilemmas were chosen because of the fact that they stand out after comprehensive review of the relevant literature regarding the Holocaust and post-Holocaust eras. Each dilemma is followed by two alternative solutions - deontological moral based solution as opposed to survival moral based solution. All of the dilemmas and all the solutions provided are historically authentic. Participants were requested to indicate their personal attitude concerning the two suggested different solutions, A or B, for each dilemma on a 5-point Likert scale where 1 = strongly disagree, and 5= strongly agree. They could choose to relate to one solution (A or B), or to both solutions, A+B. Alternatively, they could mark the response “I have no opinion” or write a solution of their own.

Data analysis

Inferential statistics including repeated measures profile analysis were used to describe the mean results that illustrate the evolution of participants’ attitudes. A two-way ANOVA model was used for each analysis, in which the first factor was the intervention and the second factor was the moderator. F constitutes the statistical indicator in each analysis regarding the interaction between the intervention and the moderator. A statistically significant F for the interaction means that the two comparison pairs evolved in a significantly different way from one measurement point to another. This kind of result suggested a moderation effect which was then further investigated by targeted comparisons using t-tests and the effect size indicator (d).

Research limitations.

This was an exploratory research, which as far as we could ascertain was the first study on the subject of Israeli high school students' perceptions over their moral attitudes towards Holocaust moral dilemmas. Therefore, there were no other results from similar research studies that we could compare with our results. This limitation could be overcome by further research on this issue.

Findings

A family relative who was a Holocaust victim or survivor as a moderator.

The results relate to the Category–

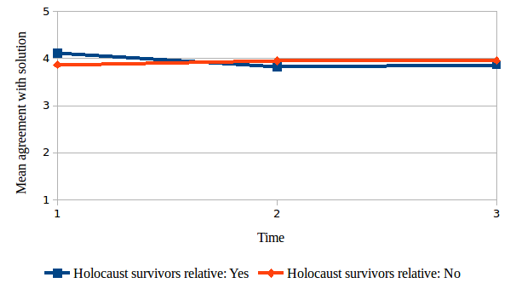

A significant interaction effect (F=3.156, p<0.05) was found between the Holocaust Learning Program and the moderator 'having or not having a relative who was a holocaust victim or survivor’ in the evolution of “agreement” with the 'acceptance' moral solution (4b) (Figure

II. Gender as a moderator

The results relate to the Category -

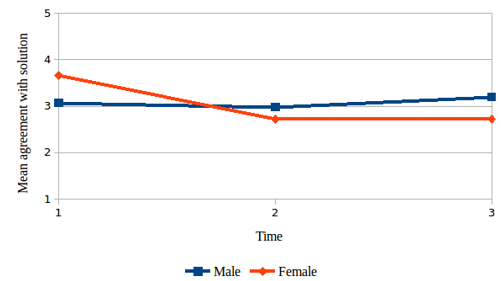

A significant interaction effect (F=5.45, p<0.01) was found between the Holocaust Learning Program and gender in the evolution of agreement with the affective-intuitive moral solution (5a) (Figure

Conclusion

Discussion on differences associated with ‘having or not having Holocaust survivors or victims as relatives:

The results indicate that a significant difference in the evolution of the participants' agreement with the 'acceptance moral solution' was only found with regard to the dilemmas’ category - "The Perception of Jewish behaviour towards the Nazis", between the group of students who had relatives who were Holocaust survivors or victims and those who did not have such relatives. Among the participants who had a family connection to Holocaust victims or survivors there was a significant decrease in the level of agreement with the 'acceptance moral solution', while for the participants who did not have such a family connection there was an opposite process of insignificant increase in the level of their agreement with the 'acceptance moral solution'.

How can we explain this difference? Former research has emphasized the great emotional sensitivity of those who have relatives, who are Holocaust victims and/or survivors to anything relating to the Holocaust (Fuchs, 2009). Nevertheless, from a psycho-social and historical aspect it is now more possible for the third and fourth generations to develop new perceptions of the Holocaust and new directions of thinking (Litvak-Hirsch & Brown, 2008). A possible explanation is that although family members of Holocaust victims and survivors did embrace the 'acceptance moral attitude' at the beginning of learning and continued to hold this attitude when learning continued, they also had emotional difficulty to really accept the Jews’ helplessness in the face of Nazi aggression with so much understanding. This interpretation is supported by the claim of Guglielmo, Monroe & Molle (2009) that emotions have a significant, if not decisive influence on thinking and especially on moral decisions concerning moral dilemmas. Reinforcement for this view is given by Aquino & Reed, (2002) who found that personal states and specific circumstances will have significant influence both on moral judgment and also on moral decision-making. The conclusion is that the initial emotional instinctive tendency among relatives of Holocaust survivors or victims, to accept the “passive” way that Jews behaved towards the Nazis, was reduced by the learning process although it still remained supportive.

Discussion on differences associated with gender

The results revealed two cases of gender differences which will be discussed here:1. In the category - "Consideration of revenge and compromise “a significant difference was found between boys and girls in the evolution of their level of agreement with the 'affective-intuitive moral solution'. Both boys and girls decreased the level of their agreement with the 'affective-intuitive moral solution' over the one-year learning program, but while for the girls it was a significant decrease to the level of disagreement, the decrease in the boys’ level of agreement was not significant. These results are in line with those of Greene et al. (2007), which indicated that women may experience stronger affective responses to harm than men, leading to systematic gender differences in deontological judgments. The conclusion is that girls were more affected by the cognitive aspect of the learning process, were more realistic, less emotional and had less desire to support killing of Nazis as acts of revenge. At the same time boys were more affected by emotional reasoning and hade more desire to support acts of revenge against Nazis...

References

- Aharonson, M. (1999). Memory as history and history as memory, Israel: Ramat Gan Museum.

- Aquino, K., & Reed, A. (2002). The self-importance of moral identity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 83(6), 1423-1440.

- Bar-On, Dan (1994). From fear to hope. Israel: The Ghetto Fighters House and the Kibbutz Hameuhad. [Hebrew]

- Barley, Michael (2007). The third Reich, a new history. Trans. Edit Zartal. Tel Aviv: Zemora-Bitan and Yavne Publishers.

- Foot, P. (1967). The problem of abortion and the doctrine of double effect. Oxford Review, 5, 5–15.

- Fuchs, Nicole (2009). Your history is part of me: American Jews second and third generation Holocaust survivors and the trans-generational transmission of memory, trauma and history. Anthology of the Heritage of the Holocaust and Anti-Semitism 4(87), December, 9-39. Publication of Moreshet, Mordechai Anilevich House of Testimony, the Stefan Roth Institute for the Study of Anti-Semitism and Racism, University of Tel Aviv. [Hebrew]

- Gampel Y. (2005). My parents live through me. Children of the war. Jerusalem: Keter Books Ltd. [Hebrew]

- Gottwein, D. (1998). Privatization of the Holocaust: Politics, memory and historiography. Pages for the research of the Holocaust. Collection 15. Israel: Institute for the Research of the Holocaust Period, University of Haifa and Ghetto Fighters House Publications. [Hebrew]

- Graham, J., Iyer, R., Nosek A. B., Haidt, J., Koleva S., & Ditto H. P. (2011), Mapping the moral domain, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, American Psychological Association 101(2), 366–385.DOI:

- Greene, D. J., Morelli, A. S., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, E. L., & Cohen, D.J. (2007), Cognitive load selectively interferes with utilitarian moral judgment, Cognition 107 (2008) 1144–1154, DOI:

- Greif, Gideon, Weitz, Yechiam, & Machman, Dan (1983). In the days of the holocaust. Units 1-2. Jerusalem: Open University. [Hebrew]

- Guglielmo, S., Monroe, A. E., & Malle, B. F. (2009). At the heart of morality lies folk psychology. Inquiry, 52, 449–466.

- Kohlberg, L. (1973). The claim to moral adequacy of a highest stage of moral judgment. Journal of Philosophy 70(18), 630–646.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village statistics 1945, Classification of land and area ownership in Palestine. Beirut: Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Litvak-Hirsch, T. & Braun, D. (2008). Three generations of mothers after the Holocaust: Trans-generational transmission from a grandmother Holocaust survivor to her daughter and granddaughter. In R. Fisher (Ed.) In the spaces of memory, creativity of the second and third generations of Holocaust survivors. Israel: Ghetto Fighters House, Laor Publishers and Keter Publishers. [Hebrew]

- Machman, D. (1998). The Holocaust and its research – Conceptualization, terminology and fundamental issues. Tel Aviv: The Mordechai Anilevitch House of Testimony. [Hebrew]

- Orbach, A. (2010). Survivors. Jerusalem: Yad Yitzhak Ben-Zvi. [Hebrew]

- Steev, I. (2002). Jewish demography of our times: Zionism and the establishment of the state. Tel Aviv: Jewish Agency. [Hebrew]

- Weitz, Y. (1997). From vision to revision. Tel Aviv: Zalman Shazar Centre for Israel History. [Hebrew]

- Worgen, Y. (Ed.) (2008). Youth Delegations to Poland. A document submitted to the Knesset Education Committee. The Knesset Research and Information Center.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

25 June 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-062-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

63

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-613

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Efrat, S., Pintea, S., & Baban, A. (2019). Moderators Of Change In The Attitudes Toward Holocaust Moral Dilemmas. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2018, vol 63. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 153-161). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.06.20