Abstract

In Chile, the educational approach on public health issues is addressed by taking into account the perspective of professionals based purely on epidemiological data with no consideration for the needs felt by the community. This results in health policies that do not satisfy the real sanitary demands of the users. In the light of the aforementioned, it is important to consider the community as the protagonist in the decision making pertained to the educational content provided by experts as this will affect their self-care behaviors.

Keywords: Community empowermentfelt needshealth behaviorsnursingparticipatory diagnosisself-care

Introduction

A few years ago, health issues in Chile were addressed considering more complex health care approaches, this is when the state of health has deteriorated and the disease has spread. Nowadays, sanitary strategic objectives were created thanks to the approach of health objectives for the decade of 2011-2020, which guide the formulation of health policies in our country (Ministerio de Salud, 2018). In this context, the purpose of the Government in health matters is to reverse the actual situation aiming that the issues in this area are solved focusing on health promotion and prevention. The importance of this orientation relies in avoiding diseases through self-care, with the practice of healthy habits, decreasing morbimortality, which translates into lower economic expenses in higher levels of care and thus also an improvement in society’s quality of life (Ministerio de Salud, 2017). This is why in 2012, the Health Promotion Programme was approved searching to act in the first levels of care: Promotion and prevention (Ministerio de Salud, 2014). Despite the efforts made, this strategy has not given significant results because the implementation of the previously mentioned approach has not been achieved in all health services.

The sanitary objectives for the 2011-2020 period are focused on encouraging health promotion actions, developing healthy environments and healthy life styles. Health education is also considered as a linchpin to accomplish these goals. Within this context there is room for participatory methodology and/or diagnosis, which is a democratic opportunity for the community to be a leading force and partake in the decision making regarding the health content they want to learn. The usage of participatory methodology and diagnosis is based on the fact that it allows a better understanding of some realities, its problems and causes, while giving particular relevance to the perspective of those living in this community, while encouraging them to look for plausible solutions and proposing shared solutions, public and private institutions (Ministerio Secretaría General de Gobierno, n.d.). Participatory methodology manages to raise genuine educational needs in health for the community, thus being able to focus resources into solving them and contributing to bolster promotion and prevention actions. This is due to centering the community in their own learning process in health, considering their previous knowledge and their personal motivations, so it ensures that their healthy behavior in health will be real and long lasting in time (Marriner & Raile, 2011).

Purpose of the Study

The objective of this article is to identify and describe the felt needs of different community groups located in the city of Santiago, Chile.

Research Methods

Context

The course “Nursing Interventions in Community Health” of the Community Nursing professional section of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile has Service-Learning as its methodology, which contributes to improve students’ learning through working with communities facing their actual issues, thus complementing both academic aspects and values of university education.

In the courses’ framework, educational interventions were carried out in different communities around the city. All of the subjects assigned to the different communities were obtained in the participatory diagnosis of each one of the communities. This tool constitutes a democratic opportunity for the community to take place in the decision-making concerning their educational health needs.

Steps of Participatory Diagnosis

Steps of Participatory Diagnosis, dynamic adaptation of “treasure hunt” of the Popular Education Participatory Technique book written by María Silvia Campos, professor of the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile (UC) Nursing school

Step Nº1: To look for diagnosis subjects

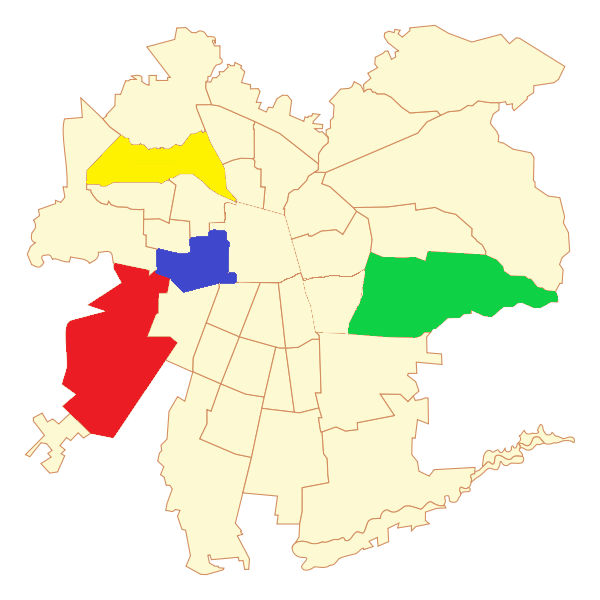

To accomplish with the course’s objectives, a link was made with UC’s Puentes UC program belonging to the Public Policies Center UC of the same university that contributes to the realization of projects that help solve public issues around the country. This organization helped contacting community groups in four municipalities of Santiago (Renca, Peñalolén, Estación Central and Maipú) (Figure

Step Nº2: To take in consideration the health issues and needs affecting the community.

The participatory diagnosis sessions were made during the third week of March of 2018, consisting of an opening dynamic to break the ice as most of the participants did not know each other. An individual survey was also applied in order to know what health educational content they wished to learn. Afterwards, groups were made in order to socialize and discuss the ideas they had after the survey they previously answered. Lastly, all gathered in a joint session with all the community. In this space, the main issues brought up in each group were established and a decision matrix was made to prioritize topics of interest and to determine which were the topics that they wanted to address in their community.

Step Nº3: To sort, select and prioritize the problems that will be crafted by the team.

The methodology envisages the usage of a tool known as decision matrix that sorts the topics of interests according to four concepts: Magnitude, Transcendence, Feasibility and Cost. Magnitude involves how many people are affected; Transcendence refers to the sanitary impact made the issue (severity); Feasibility is the possibility of having enough materials and human resources to make changes in order to solve the issue, and Cost is tied with the expenditure that would take to carry out the intervention or change which should be linked to potential benefits and then determine if these equate or surpass the cost.

Step Nº4: To analyze the causes of the selected problems in the previous step.

In this stage, the behaviors that influence the existence of the selected problem were evaluated. This was done considering the factors that favor, predispose and reinforce such behaviors. For this step, it was adequate using the “Problem tree analysis” tool because it is useful in analyzing cause-effect relationships of a problematic, verifying logic and the integrity of the whole scheme. This project planning is elaborated by defining the main problem as the stump of the tree, while the essential causes are roots and the effects are the tree top branches.

Step Nº5: To identify the local resources, organizing steps and efforts made to solve the issue(s).

In step number 5, it is established in what ways can the group contribute solving the identified problems and how these problems are sorted to carry out the interventions. A “Group Contract” was used for every community in which the work conditions for the realization of the sessions were defined. This was made in order to create and maintain an environment that fosters values and commitment within the group.

Findings

The main results have been divided according to the steps of the participatory diagnosis methodology.

Step Nº1: To look for diagnosis subjects

The sample size is composed by 48 people, where 96% of them are self-identified as female. The age range is constituted by people between 25 and 83 years old, with an average age of 55,9 years old. Regarding health aspects 69,8% of the sample had a chronic condition where arterial hypertension and diabetes mellitus type 2 prevailed, which were mostly treated by public healthcare services.

Step Nº2: To take in consideration the health issues and needs affecting the community.

From the applied survey and the group discussions, the topics that were to be addressed in the next sessions were revealed. There were 20 different contents to be worked on, which were not sorted hierarchically. Among these contents, first aid basic elements were highlighted, such as: Fall prevention, bug bites, fever treatment, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), the Heimlich maneuver, management of burn wounds, emergency childbirth, strokes, myocardial infarction (MI), epileptic seizure. Regarding healthy habits: Healthy eating, anxiety and stress management, active mind, sleep hygiene and physical activity. Finally, those that could not be categorized were: Elder/aged care, menopause/climacteric, non-transmissible chronic diseases, temper tantrum management and caregiver burden.

Step Nº3: To sort, select and prioritize the problems that will be crafted by the team.

The participants shared their felt needs and identified the main topics of interests of health through a decision matrix. The main results are divided into: CPR, Heimlich maneuver; healthy habits: Healthy eating and stress and anxiety management. Table

Step Nº4: To analyze the causes of the selected problems in the previous step.

The causes of the community problems were discussed with the usage of the “Decision Tree” tool. Within each commune a variety of issues stood out:

Renca: Caregiver burden, pressure to act as a caregiver effectively, high expectations, relative affected by a psychiatric pathology.

Peñalolén: Lack of time, lack of knowledge on health topics, grandchildren caring.

Estación Central: Children and/or grandchildren caring, previous experiences in emergency situations, lack of knowledge on health topics.

Maipú: Ignorance and misconceptions in health issues, lack of time.

It is important to consider that although similar topics were addressed by every community, they were all addressed differently by the team due to the difference in the root causes of each of the communities.

Step Nº5: To identify the local resources, organizing steps and efforts made to solve the issue(s).

Through the “group contract” tool the communities defined non-negotiable minimum standards for the educational sessions. These were: Punctuality, attendance, unity, teamwork, respect and tolerance, confidentiality and fellowship.

Discussion

In the early 70s, the Chilean health system incorporated new approaches and socio-cultural variables into community work, with the aim of changing its paternalistic and welfare-oriented system. For this new approach, the system required new

Within the results found in the community groups in Santiago it is possible to recognize a great similarity in the educational felt needs. This situation enables to take in consideration the importance of health education and participatory diagnosis, which serves as a tool that eases priority problems identification that are important for society.

The World Health Organization (WHO) refers to “Education for Health” as a set of educational activities designed to broaden the knowledge of the population in terms of health and to develop knowledge, attitudes and skills that promote it, making this education an indisputable instrument for health promotion (Gobierno de Navarra, 2006). This work contributes to the empowerment of individuals, trying to make them actively participate in defining their needs and to elaborate proposals in order to achieve certain goals in health (Riquelme Pérez, 2012). This may be possible thanks to participatory diagnosis, since community members are able to feel heard and take an enthusiastic role in learning. Therefore, granting community members the chance to partake in the decision making of the content and topics proposed to learn provokes them to feel relevant on their own learning (Vella, 2002).

In an issue of the magazine Enfermería Global on the development of community nursery in Argentina, it was stated that the type of community work used is the so-called Community-based Education. This model focuses mostly on health issues, which are recognized throughout the process as priority by the team and the community group. From the aforementioned it is possible to account that participatory diagnosis is also employed in Spain country (Villalba, 2008).

Furthermore, in line with the analysis obtained through the participatory diagnosis, the proposal of this work is to use the described methodology in health education, not only in communities, but also considering its importance in varied sectors of healthcare. In addition, there should be intersectoral collaboration to strengthen health prevention and promotion through participatory methodologies. As it was seen in these interventions, user participation in the decision making on the contents to be learned means that there is a significant learning allowing self-empowering, an increase in self-efficacy and motivation in behavior change, which is fundamental for selfcare.

Conclusion

Based on the work carry out with the communities, the importance of using participatory diagnosis is reasserted, as it is a tool that enables the team to: Learn and prioritize problems and/or needs that are affecting group members, considering the severity of them, the urgency of the solution and the affected population; To build knowledge with the community and act upon reality; To obtain information for intervention planning for short, medium and long term; And to achieve participation of community members in the decision making (Gonzalez, 2015).

Before propounding an intervention, it is necessary to get to know the reality of the community, its physical environment and epidemiological characteristics. This is the reason why there is an identifying needs process, which is the first phase in the planning process. This will let us define the most appropriate goals and activities for the needs and collective reality that the team will work with (Riquelme Pérez, 2012).

Gonzalez, part of the Ministry of Health of Chile (2015) states that to contribute to the sustainable development of the communities we should start acknowledging the populations life conditions, their social, politica, economic and cultural reality. By taking on account their reality, the person can become the agent and subject of the changes that are taking place in his/her community.

Finally, it is essential to continue with the research on used methodologies for health education and the relevance of participatory diagnosis as the first interaction with communities as this entails the significance degree in the learning that users will have. Thereby, qualitative and quantitative results of the impact of having people as the main role and active agents for the development of knowledge, educative process, empowerment and self-care behaviors can be obtained.

Acknowledgments

We thank our mentor and guide in this community interventions process, María Sylvia Campos, professor at the Nursing school at the Pontifical Catholic University of Chile, who was without a doubt fundamental in our academic formation as future community nurses. Her phrase

References

- Gobierno de Navarra (2006). Manual de Educación para la Salud. Pamplona: ONA Industria Gráfica

- Gonzalez, N. (2015). Trabajo Comunitario en Salud. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de Salud.España.

- Marriner, A., & Raile, M. (2011). Modelo de promoción de la salud. In R. Marriner (Ed.), Modelos y teorías en enfermería (pp. 434-445). España: ELSEVIER.

- Ministerio de Salud (2014). Orientaciones para planes comunales de orientación de la salud 2014. Retrieved from: http://www.minsal.cl/sites/default/files/orienplancom2014.pdf

- Ministerio de salud (2017). Encuesta Nacional de Salud 2016-2017. Santiago, Chile: Ministerio de salud

- Ministerio de Salud (2018). Objetivos Estratégicos. Retrieved from: http://www.salud-e.cl/plan/objetivos estrategicos.

- Ministerio Secretaría General de Gobierno. (n.d). Elaboración de Diagnósticos Participativos. Retrieved from: http://www.gobiernoabierto.gob.cl/sites/default/files/biblioteca/Serie_5.pdf

- Riquelme Pérez, M. (2012). Metodología de educación para la salud. Pediatría Atención Primaria, 14, 77-82. DOI:

- Servicio Nacional de Discapacidad. (2015). Algunas herramientas de apoyo para el trabajo comunitarionen salud. Retrieved from: http://www.sstalcahuano.cl/file/jornada_gg/MANUALALGUNASHERRAMIENTASTRABAJO.pdf.

- Vella, J. (2002). Twelve Principles for Effective Adult Learning. In J. Vella (Ed.), Learning to Listen, Learning to Teach: The Power of Dialogue in Educating Adults (pp. 3-28). Retrieved from: http://www.untagsmd.ac.id/files/Perpustakaan_Digital_1/ADULT%20LEARNING%20Learning%20to%20listen,%20learning%20to%20teach%20%20the%20power%20of%20dialogue%20in%20educating%20adults.pdf.

- Villalba, R. (2008). Desarrollo de la enfermería comunitaria en la República Argentina. Revista Enfermería Global, 7(2), 1-10. Retrieved from: http://revistas.um.es/eglobal/article/view/16111.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Canales, C., Correa, C., Cruz, A., Ferrada, C., López, M., Rencoret, B., Valenzuela, I., & Vargas, J. (2019). Participatory Diagnosis: A Methodology To Identify Felt Needs In Communities In Chile. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 473-480). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.60