Abstract

We present the results of an investigation with Primary School students in the 5th grade through an Exploratory Case Study. The research design allows us to identify the meanings constructed by the students from the practice of mindfulness over 3 months through both individual and group interviews, participant observation and focus groups, where we show that students acknowledge the wellbeing resulting from the times in the classroom dedicated to relaxation and introspection, which helps them to be more proactive, have greater focus on school tasks and adopt a calmer attitude when facing conflict. The students’ discourse highlights the value of promoting the development of personal skills and strengths such as self-listening, non-judgmental, sensory and body perception; an interesting line of future research would include an in depth look at how these skills impact, -and the resulting effects-, the areas indicated previously. Thus, we propose the need to anchor the research on mindfulness in an educational approach that recognizes the social function of schools at present. We discuss the need to conduct a mixed research design to identify the impact of mindfulness on the improvement of emotional, social and conflict resolution skills and the improvement of academic performance.

Keywords: Basic educationcurriculumcase studymindfulnesspersonal wellbeing

Introduction

It is evident that we live in a fast-paced society, with many obligations, many social and professional commitments and with little time for ourselves, to listen to ourselves, to understand what it is we need, really need. These are needs that are often set by the market and by a consumer culture, which requires reflection on the prevailing model of society (Bauman, 2006). Childhood and adolescence are not alien to these circumstances, and in the context of their daily lives, children and adolescents experience relationships, activities and a daily load of heavy burdens that remove them, as with most individuals, away from a complete awareness of their lives.

The object of this study aims to link mindfulness with improvements to teaching practice, by assessing the importance of establishing working conditions that promote the mental and emotional wellbeing of students in the classroom, a prerequisite and starting point for relevant learning and the development of harmonious social relationships in schools. We are aware that this subject may be considered to be a passing trend, and as such could be treated superficially; however, teaching experiences in schools have allowed us to see the work needed, with today’s youth, to devise procedures that will allow them to focus on school work, to stop to listen to their inner voices and start to learn in a relaxed and quiet way.

A current need that we understand endows mindfulness with educational value. Children and adolescents, as a correlate of the lives of adults, are often subjected to a pace of life and social and family dynamics whose effects become evident in the classroom. We understand that many of the diagnoses of hyperactivity, for example, are just an expression of social problems that schools then reify or objectify by deeming these problems to be individual deficits.

Technological environments, while offering a multitude of rich educational experiences, can also subject children and adolescents to behaviours and activities that are far removed from the concentration and discipline that learning requires. Discipline should be understood as a learnt skill, and not as a result of an authoritarian education, a context where rules are enforceable under a model of punitive coexistence.

We conceive discipline as a trait of any democratic education that requires the rules of the game to be agreed upon and legitimized by teachers and students, as defined by Defrance (2005) in his work on school discipline; a discipline that is consubstantial to the structure of education itself as it is in influencing new generations in a systematic, conscious and perfective way (Gimeno, 2003; Pérez, 1995, 1998). But this educational mission has become a more complex task because the contexts that children inhabit have become more dynamic, less stable and more mobile, and to paraphrase Bauman (2006), we could say they have become even more fluid. Although we have active and participatory methodologies at our disposal, as well as new competency frameworks to work within (European Commission, 2018), where conceptual content is the means for the development of those competences, devaluing rote learning, this does not mean that students are no longer required to make the effort inherent to meaningful and relevant learning. To this we must add one more reflection, as Fernández-Enguita (2017) have recently suggested, which is to question the extent to which -and its resulting consequences - educational content has been reduced to teaching, and its organization, to the classroom. We agree with this author that the classroom embodies everything that was once the school of modernity and today is a heavy nineteenth-century burden: the bureaucratic categorization of students, the one size fits all goals and processes, the boredom of some and the frustration of others, the routines that kill creativity.

For all these reasons, we have determined that this body of research provides an alternative to systematically assess, analyse and understand the educational relevance of mindfulness in education. The reflections and ideas embodied here derive from a study constructed through the voice of students, as well as other instruments used to collect information, which will help us understand the implications that mindfulness may have in the development and education of students as citizens of the 21st century.

Problem Statement

The term mindfulness comes from the Middle East and has been imported, mainly, by Buddhist monks who, over the years, have been highlighting its benefits across various fields of research, including among others, in education. Miró (2006) and Simón (2006) have even come to affirm that we all practice mindfulness when we are in contact with the present reality, and we show awareness of this in our actions; for example, when we are drinking water and feel how it moves down our pharynx, or when we feel each step we are taking while walking.

For Gunaratana (2012), a prestigious Buddhist monk, reaching a state of mindfulness is not something simple because it requires energy and personal effort, and he notes that cultivating mindfulness requires delicate and gentle effort, which serves to remind us of the need to be aware of what is happening in the here and now through perseverance and gentleness. That is, trying to return, gently and repeatedly, to a state of focus.

In an Anglo-Saxon context, Siegel, Germer, & Olendzki (2009) and Siegel (2011), affirm that mindfulness requires three conditions: non-judgment, acceptance and compassion.

In the same vein as Lutz, Dunne, & Davidson (2007), Miró (2006) and Simón (2006), we define mindfulness as a non-linguistic, non-religious and non-conceptual activity that refers to the mental function of focusing our attention on something (an object, a situation, etc.) for an undetermined period of time.

The renowned Buddhist monk Kabat-Zinn (2003, 2007, 2012), a pioneer of mindfulness to the Western world, describes the attentive way of observing characteristics typical of mindfulness, as a process involving the observation of body and mind that allows one's experiences to continue to unfold moment by moment and to accept these as they are. Likewise, mindfulness also emphasizes that it is not about rejecting ideas or trying to suppress or control them, but rather to allow ourselves to be where we already are and to experience the various moments of our lives in a more present way. Therefore, he argues that this type of meditation is conceived as a practice open to any human, and that it will serve to alleviate the unnecessary suffering of daily life and improve coexistence among peers as a result of a mastery of various negative emotions.

In short, mindfulness consists of paying attention, intentionally, to the present moment without judging ourselves. Thus, Hanh (1975, 2015) synthesizes mindfulness as consisting of the observation, not condemnation, of the flow of all stimulation.

The concept of mindfulness has also been defined by other authors, such as Bishop et al. (2004), as a metacognitive ability; as a self-regulating capacity (Brown and Ryan, 2003); as an acceptance skill (Linehan, 1994); and as a term of attention control (Teasdale, Segal, & Williams, 1995). Although, as pointed out by Gunaratana (2012), mindfulness cannot be fully explained with words because of its subtle nature, but as an experiential and non-verbal experience.

In the same way, Ruiz (2016) states that through mindfulness three main dimensions are worked on: 1) attention practices; 2) body awareness practices, and; 3) integrative practices that promote full attention in daily life.

In summary, mindfulness is viewed as a producer of great benefits in the types of practices to develop consciousness and complete focus that help practicing individuals live in a more conscious way, with more ease and less judgement when looking at their own life experience.

In this way, we aim to understand whether meditative techniques associated with mindfulness can be a valuable asset to schools by looking at its educational value to promote this type of self-knowledge and self-listening for students, which will allow them to live in a more conscious and meaningful way.

Research Questions

This study focuses on understanding the opinions of students in a mixed gender, 5th grade class of 27 primary school students at an educational institute located in Cuenca, in Spain, after the practice of a mindfulness program.

To do so, the research questions focus on revealing the students’ perception of their personal growth and the usefulness of mindfulness in their daily lives. Specifically, it aims to offer an answer to the following questions:

What aspects of mindfulness do students acknowledge as relevant in relation to their personal and academic experiences?

What moments of their experience are identified by students as benefits of their practice of mindfulness?

Are there aspects that they explicitly recognize as related to their emotional and social development?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of this study is to uncover, first-hand, the contributions and evaluations of the mindfulness meditation practices of the aforementioned group of 5th grade primary school students. That is, we aim to understand the extent to which this practice has enriched them as people (individuals) and has helped them to develop in an integral way; so, we present the initial results of the study, where the students' voices have been recorded regarding mindfulness, specifically its usefulness and their interest and liking of this practice. Using the students’ experiences, the aim is to identify the possibilities of these techniques to understand their relevance as the object of a more in-depth and exhaustive investigation. We want to assess the relevancy of mindfulness as an object of study to analyse the understand the suitability for further research, identifying whether it contributes to a personal growth more focused on students' self-knowledge and development, more specifically in their emotional management and the development of skills that improve coexistence.

Research Methods

The context of the investigation

This research is part of the implementation of a mindfulness program in a school of Infant, Primary and Secondary Education in Cuenca (Spain) with a heterogeneous group of 27 students from a mid-high socioeconomic background.

This program began in October 2017, with an expectation that it would be extended across the entire academic year. Thus, this article presents the preliminary results after 12 weeks of implementation. Mindfulness practices have been carried out in 2-weekly sessions of between 20-40 minutes, as well as in 5 minutes sessions for the various evaluation tests conducted.

Method

A case study has been carried out with a type of exploratory research using qualitative data (Hernández, 2010). The case studies allow us to understand the phenomena within the environment the participants are immersed, and to generate knowledge taking into account the richness and complexity of the reality, in our case, to identify how the students value the contributions of mindfulness within a school experience. "A case study provides a unique example of real people in real situations, enabling readers to more clearly understand ideas than by simply presenting them with abstract theories or principles" (Cohen, Manion, & Morrison, 2011, p.289).

Data collection techniques

The instruments used for data collection include:

3 focus groups of 9 students, aimed at generating a debate and discussion of different phenomena that have occurred in the classroom, so that all students have had the opportunity to express themselves, to give their opinion, enabling us to record their points of view.

Informal interviews held with students, and mirroring Taylor and Bogdan (1996), face-to-face scenarios were proposed, enabling intimate conversations with a reciprocal exchange of information.

Participant observation, the instrument being the descriptive and interpretative field notebook (Velasco and Díaz de Rada, 2009). It is considered necessary that, as noted by Santos (1999), the eyes are educated to see and that the mind is trained so that different situations enable the research group to decipher the meaning of what was observed.

All these instruments have been used to triangulate the data, as stated by Creswell (2008), and to promote the analysis and understanding of student intersubjectivity, where, as Merlau-Ponty (1985) puts it, qualitative research constitutes a dynamic process, given that the distinction between the objective and the subjective world is not so differentiated, with both making reference to the same empirical reference.

Findings

The students propose a series of advantages and utilities of mindfulness that significantly exceed the expectations set at the beginning of the investigation. They talk about the different aspects that they recognize as constitutive elements of their experience: social skills for conflict and emotional management. Likewise, significant improvements have been observed and recorded in the way students approach educational activities, including those students who have the greatest difficulties in maintaining attention and behaving adequately in the classroom.

Emotional competence

In regard to emotional management, the students argue that practicing mindfulness for a few minutes helps them de-stress and relax enough to take the class in a more relaxed and calm way. Along the same lines, they also argue that it helps channel the fatigue and exhaustion caused by long school days.

An interesting aspect to be analyzed with more reliable and consistent data, and to guide the research towards how mindfulness could favor the active and real participation of the students in the classroom.

When we are very, very tense, we practice mindfulness and it relaxes us a lot (FS).

I think it’s very good because when we're angry or very distressed, practicing mindfulness relaxes me very much (MR).

These data are important because schools prioritise efforts, but do not take into account other contextual factors that allow children to learn to manage the degree of effort with teachers, and to deploy the conditions in which the entire class can experience the tranquillity and calm necessary to work at ease. As the students recognize, they sometimes need a return to calm after recess. This is an interesting aspect that should be studied using more reliable and consistent data, directing this research towards how mindfulness could favour the real and active participation of students in classroom life.

Management of social skills

At the same time, students claim that practicing mindfulness benefits them in the resolution and management of conflicts and in the improvement of their social skills, since the practice of mindfulness helps them to stop, calm down and try to find a peaceful solution, promoting relaxation and dialogue, breaking with the dynamics of anger and tension typical of these types of situations.

When we are angry with someone, we relax and, in this way, we can talk more calmly and solve the conflict better (BD).

These data indicate a need for in-depth study of the value of mindfulness in the learning of conflict resolution. It is important that at an early age, children are taught in school to face disagreements with and among peers, a type of confrontation that requires a calm and sincere dialogue, so that they learn to take responsibility for interpersonal relationships as an aspect of humanity that must be cared for and confronted with autonomy.

How students face testing

A constitutive aspect of their experience that is noteworthy is that a majority of the students identify mindfulness as a practice that helps them to face situations that assess learning. Those moments before a test are times in which students can feel some stress or nervousness and, as they openly admit, practicing mindfulness for a few minutes helps them to manage this state of stress, to calm down, to refresh their memory and to focus more on the test’s questions and corresponding answers.

When we are tired of the day, mindfulness helps me to relax and feel good about myself (DT).

I find it very useful to practice mindfulness at the beginning of an exam, because we are a bit stressed and nervous and doing it relaxes us (FQ).

We are more relaxed and can focus more on the answers (BD).

These first exploratory results lead us to consider mindfulness as a procedure that can generate an atmosphere of calm and tranquillity in the classroom and, in this way, enable the teacher and the students to transform testing into a metacognition process. Metacognition requires relevant knowledge so that students can recognize, analyse, understand and value themselves in regard to their learning. A complex cognitive procedure that demands from children a focus and calmness that the school pace does not usually allow, and which is necessary to transform into a time of calm that focuses on the learning process and allows us to stop seeing testing as a technical activity. In view of the initial results obtained, it seems plausible that this dimension in the classroom should be explored further.

Individual cases

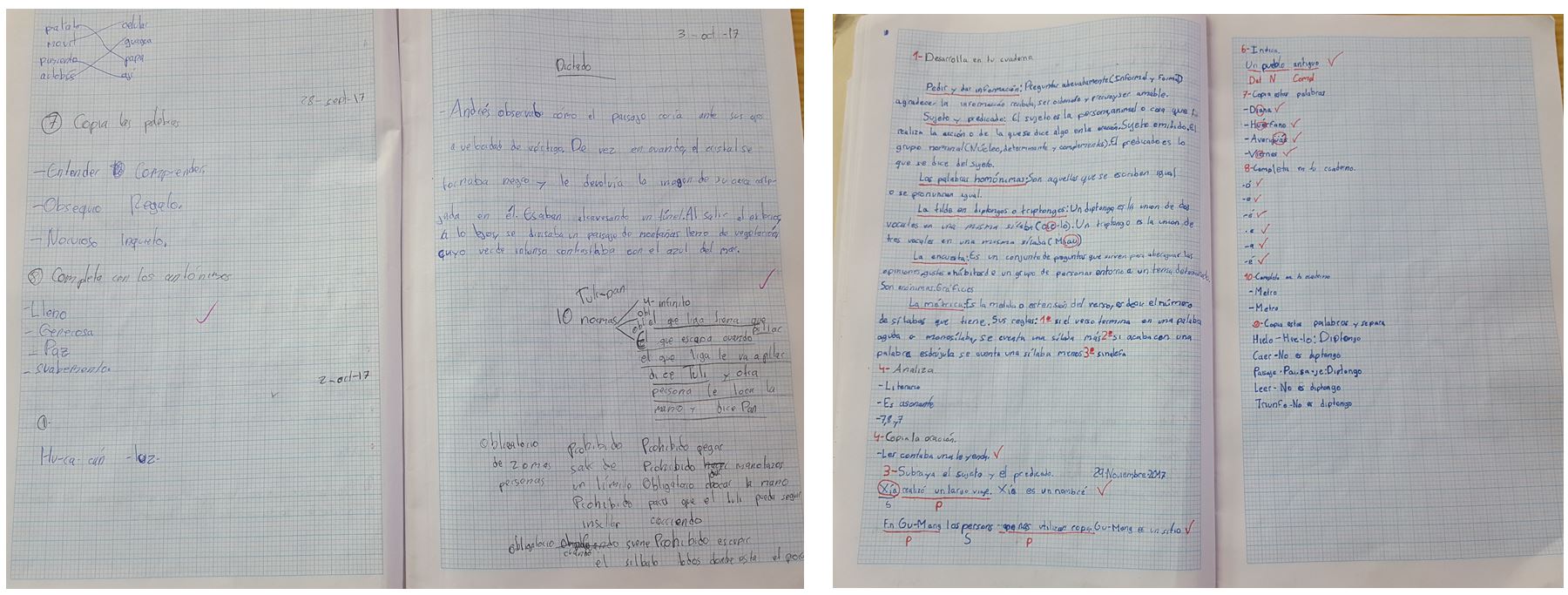

An unexpected result has been the changes observed in school work, specifically as seen on the notebook of a student diagnosed with ADHD. It is striking how this student has gradually changed his attitudes toward schoolwork, displaying a know-how knowledge that was not part of his competence at the beginning of the program.

As we pointed out in the section on the problem under study, these unforeseen results point to how mindfulness may be utilised those students who have difficulty concentrating, and as the case of ET (Figure

The two images included below highlight the significant improvements of the aforementioned student diagnosed with ADHD, who tended to be very disruptive and overactive in the classroom, and has since, following the implementation of the program, changed the ways in which he writes in, and organizes his notebook.

Conclusion

The results, though exploratory, expose the need to address an in-depth debate and reflection on the need and utility of including mindfulness practice within the educational curriculum. We observe how the practice of mindfulness is acknowledged by students as a set of experiences in which there is a display of diverse skills, including: emotional competence and management, social skills, coping skills ahead of tests and school work evaluation, and conflict management and resolution. We now propose a more in depth analysis of the program, in this way delving into unforeseen aspects; including identification of an objective to understand the curricular areas that can be improved by introducing mindfulness in the classroom as a future research area. Similarly, it seems striking to think that if students positively value mindfulness, it would worthwhile, and even necessary, to take into account the voice of students, active agents of the teaching-learning processes that takes place in schools, and to do it with data collection techniques that are less intrusive and more projective, such as audio-visual records and their use based on the premises of audio-visual anthropology. The preliminary results suggest that students could grow in their intrapersonal intelligence, in emotional management and in the improvement of their social skills, which are fundamental elements to live in society in a full, responsible, conscious and competent way. But also, as the results obtained indicate, introduce certain improvements in the curriculum, such as evaluation, and even help develop or strengthen certain personality traits of the teacher such as patience, prudence, a type of impartiality that does not judge arbitrarily, good sense and with it, generosity.

There is no doubt that it is necessary to deepen the findings collected to date, and try to investigate, in greater depth, the implications of the practice of mindfulness in the areas outlined as well as in other areas or aspects that are as yet unforeseen.

References

- Bauman, Z. (2006). Vida líquida. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

- Bishop, S. R., Lau, M., Shapiro, S., Carlson, L., Anderson, N., Cardomy, J., Segal, Z., Abbey, S., Speca, M., Velting, D., & Devins, G. (2004). Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 230-241.

- Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The bennefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84, 822-848.

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research Methods in Education. New York: Routledge

- Creswell, J. (2008). Mixed Methods Research: State of the Art. University of Michigan. Recuperado el 10/08/2017 de: sitemaker.umich.edu/creswell.workshop/files/creswell_lecture_slides.

- Defrance, B. (2005). Disciplina en la Escuela. Madrid: Ediciones Morata.

- European Commission (2018). Council Recommendation on key Competences for LifeLong Learning. Brussels. Recuperado el 8/04/2018 de: https://ec.europa.eu/education/policy/school/competences_en

- Fernández-Enguita, M. (2017). Desigualdades educativas en la sociedad digital. Zoom social. Laboratorio de alternativas. Recuperado el 14/04/2018 de: http://www.fundacionalternativas.org/public/storage/laboratorio_documentos_archivos/f8c5e395a412b93184c108d4174d1617.pdf

- Gimeno, J. (2003). El alumno como invención. Madrid: Ediciones Morata.

- Gunaratana, H. (2012). El libro del mindfulness. Barcelona: Kairós.

- Hanh, T. N. (1976). The miracle of mindfulness. New York: Bantam.

- Hanh, T. N. (2015). Plantando semillas: la práctica del mindfulness con niños. Barcelona: Kairós.

- Hernández, R. (2010). Metodología de la Investigación. Colombia: Mc Graw Hill.

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Vivir con plenitud las crisis. Cómo utilizar la sabiduría del cuerpo y de la mente para afrontar el estrés, el dolor y la enfermedad. Barcelona: Kairós (Orig. 1990).

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2007). La práctica de la atención plena. Barcelona: Kairós (Orig. 2005).

- Kabat-Zinn, J. (2012). Mindfulness en la vida cotidiana: donde quiera que vayas, ahí estás. Barcelona: Paidós Ibérica.

- Linehan, M. M. (1994). Acceptance and change: The central dialectic in psychotherapy. In S. C. Hayes, V. M. Follette, & M. M. Linehan (Eds.), Mindfulness and acceptance: Expanding the cognitive behavioral tradition (pp. 73-90). Nueva York: The Guilford Press.

- Lutz, A. Dunne, J., & Davidson, R. (2007). Meditation and the Neuroscience of Consciousness: An Introduction. In P. D. Zelazo, M. Moscovitch, & E. Thompson (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Consciousness (pp. 499-551). New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Merlau-Ponty. (1985). Fenomenología de la percepción. Barcelona: Planeta-Agostini.

- Miró, M. (2006). La atención plena (mindfulness) como intervención clínica para aliviar el sufrimiento y mejorar la convivencia. Revista de Psicoterapia, Epoca II, XVII, 31-76.

- Pérez, A. (1995). La escuela, encrucijada de culturas. Investigación en la Escuela, 26, 7-24.

- Pérez, A. (1998). La cultura escolar en la sociedad neoliberal. Madrid: Morata.

- Ruiz, P. (2016). Mindfulness en niños y adolescentes. En: AEPap (ed.). Curso de Actualización Pediatría 2016, 3, 487-501.

- Santos, M. (1999). La observación en la investigación cualitativa. Una experiencia en el área de salud. Atención Primaria, 24, 7

- Siegel, D., Germer, C., & Olendzki, A. (2009). Mindfulness: What Is It? Where Did It Come from? In F. Didonna (Ed.), Clinical handbook of mindfulness (pp. 17-35). New York, NY: Springer.

- Siegel, R. (2011). La solución mindfulness: prácticas cotidianas para problemas cotidianos. Bilbao: Desclée de Brouwer.Simón, V. M. (2006). Mindfulness y neurobiología. Revista de Psicoterapia, Epoca II, XVII, 5-30.

- Simón, V. (2006). Mindfulness y neurobiología. Revista de Psicoterapia, 67, 5-30.

- Taylor, S., & Bogdan, R. (1996). Introducción a los métodos cualitativos de investigación. Barcelona: Paidós.

- Teasdale, J., Segal, Z., & Williams, J. (1995). How does cognitive therapy prevent depressive relapse and why should attentional control (mindfulness) training help? Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 25-39.

- Velasco, H., & Díaz de Rada, A. (2009). La lógica de la investigación etnográfica. Un modelo de trabajo para etnógrafos de la escuela. Madrid: Trotta.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Benesh, N., de las Heras, A., & Rayón, L. (2019). The Value Of Mindfulness In Compulsory Education: Fad Or Need. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 251-259). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.32