Abstract

Sexist prejudice in Argentina is a current problem given that during 2017 more than 16,000 calls for gender violence were made. From a psychological perspective, ambivalent sexism is composed of hostile and benevolent sexism. The first describes the hostility towards women who do not conform to traditional gender roles and the second defines subjectively benevolent attitudes that consider women as wonderful but fragile. In addition, social dominance orientation and authoritarianism have been the most studied psychological bases that favor the emergence of sexist prejudice. However, the influence of both variables in the hostile and benevolent expressions of sexist prejudice from the ambivalent sexism theory has not yet been studied in Argentina. The aim of the study was to analyze the differential contribution of authoritarianism and social dominance in benevolent and hostile expressions of prejudice towards women. For this purpose, an ex-post facto prospective study was carried out with a total of 325 adults living in Buenos Aires. The main results demonstrated that authoritarianism influences the emergence of benevolent prejudice towards women, while social dominance turned out to be a predictor of hostile expressions. From these findings, it is necessary to rethink the contribution of authoritarianism and dominance to the different expressions of prejudice in the scientific literature when their subtle and blatant forms are not considered.

Keywords: Authoritarianismbenevolenthostilesocial dominancewomen

Introduction

Historically, women have been targets of prejudice and they were limited to certain social roles of lower status compared to men (Agarwal, 2018). Latin America in general and the Argentine context in particular were not alien to that reality (Camou, Maubrigades, & Thorp, 2016). In the argentine case, it was not until 1947 that women's suffrage was legally declared, being one of the last countries in the region to promote it (Barrancos, Guy, & Valobra, 2014). Although during the Argentine civic-military dictatorship the traditional role of women was reinforced, with the return of democracy they were included into different spheres of power in the public domain accounting for an apparent change in terms of inequality. However, it has been argued whether this change has actually occurred or if, on the contrary, we would be faced with a phenomenon of social desirability, rather than a situation of greater equality between men and women. In this sense, official data in Argentina indicate that during the third quarter of 2017 more than 16,000 women reported gender violence (Observatorio Nacional de Violencia contra las Mujeres, 2017). In addition, only in 2016 there were 254 victims of femicide, being just the 3.4% perpetrated by strangers, the rest by people close to them, mostly couples or ex-partners (Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación, 2017).

From a psychological perspective, the emergence and maintenance of these psychosocial phenomena that result in strong gender inequalities, as well as in acts of violence towards women, have been systematically studied from the Ambivalent Sexism theory (Glick & Fiske, 1996). According to Glick and Fiske (1996), sexism has been traditionally conceived as an expression of hostility towards women, without taking into account a central point: Positive feelings towards women. This feature is very important because men and women have lived together since humanity exists, and have been partners of the most intimate confidence. As a consequence of that, it becomes necessary to understand sexism as a multidimensional construct, which includes two groups of sexist attitudes: hostile and benevolent (Glick & Fiske, 1996, 2001). On the one hand, hostile sexism fits to the classic definition of prejudice proposed by Allport (1954), who considered prejudice as “an antipathy based on an inflexible and erroneous generalization, which can be felt or expressed, directed towards a group as a whole or towards an individual for being a member of a group” (p. 9). As it was previously mentioned, these kind of explicit and negative attitudes toward women are still present all around the world (Agarwal, 2018). On the other hand, Glick and Fiske (1996) defined benevolent sexism as a set of interrelated attitudes toward women that are also considered sexists because they stereotyped women and restricts their actions. Moreover, some behaviours considered as positive and prosocial by women (e.g. chivalry), by which they are considered fragile, weak or sentimental, are specific examples of benevolent sexism. As a consequence, benevolent sexism is not understood as positive from a psychological point of view, because it’s based on traditional gender roles and stereotyping that serves the male domain (e.g. male provider - female caregiver), and have negative consequences for women. For example, one of the most striking inequalities in most Western societies is the lower presence of women in management positions in different areas and organizations (Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2011): If women are weak, fragile or sentimental, then they cannot occupy leadership roles that imply coldness and severity. In this sense, benevolent sexism can be used to indirectly legitimize hostile sexism (e.g. women are more kind, sweet and understanding, that is why they should take care of their children) (Reyes Aguinaga, 1998). Although ideologies such as the superiority of the white man seem old-fashioned today, the idea of man as protector and provider continues offering a positive image that subtly reinforces the different forms of domination over women (Nadler & Morrow, 1959).

In order to assess this new way of understanding sexism, Glick and Fiske (1996) built the

Problem Statement

One of the specific variables associated with ambivalent sexism is the Gender Role Ideology (Moya, Expósito, & Padilla, 2006), based on the maintenance of traditional sexist attitudes by emphasizing the differences between sexes to relegate women to the roles of wife, housewife and mother, being finally considered as weak and in need of protection. Under this conception, man is in charge of protecting women. In order to asses this construct empirically, Moya, Navas, & Gómez Berrocal (1991) developed the Gender Role Ideology Scale with a sample of 484 students of secondary and tertiary level of professional training (264 men and 220 women), with ages ranging from 14 to 44 years (

Besides gender role ideology, sexism was related with other psychosocial variables such as centrality of religion and political orientation. The centrality of religion was defined as the degree to which precepts proposed by a particular religion guide a person’s life (Cárdenas & Barrientos, 2008) and has been found to predict benevolent sexism (Maltby, Hall, & Anderson, 2012) and right-wing authoritarianism (Fiske, 2017). However, previous studies were developed to explore the relationships among hostile sexism, benevolent sexism and religiosity in Turkey (Taşdemir, & Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2010), where Islam is the predominant religion. Results shown that when working with Christians, religiosity was a significant correlate of benevolent sexism. Conversely, when analyzing the Muslims sample, religiosity was a significant correlate of hostile sexism. Furthermore, political orientation has also been associated to sexism, particularly with right-wing or conservative ideologies that consider women should be limited to certain traditional gender roles (Christopher & Mull, 2006).

Even though the relevance of the centrality of religion, political orientation and gender role ideology to understand ambivalent sexism, psychologists have proposed other relevant variables such as right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation to understand prejudice toward women (Altemeyer, 1998). Altemeyer (1981), defined right-wing authoritarianism as the covariation of three attitudinal clusters: authoritarian submission, authoritarian aggression and conventionalism. While the first refers to a tendency to submit to the authorities perceived as legitimate in the exercise of power, the second identifies individuals willing to act aggressively towards all those perceived as potential threats to the social order. Finally, conventionalism represents the tendency to accept established social norms. The covariation of the three attitudinal clusters makes authoritarians react negatively towards those who threaten traditional ways of life and values promoted by legitimate authorities (Duckitt & Sibley, 2010).

Moreover, given that sexism is based on traditional gender roles ideologies, negative stereotypes about woman are reinforced to keep them in an inferior status position. With the aim of studying individual differences in the preference for hierarchical versus egalitarian relationships between groups, Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle (1994) proposed the existence of a social dominance orientation. Hence, the authors suggest that people higher in social dominance orientation will be more prejudiced against women considered as a low status group targeted for domination (Kilianski, 2003). Recent studies (Christopher & Mull, 2006) conducted using a representative national sample of Americans revealed that dominance, but not authoritarianism, predicted hostile sexism, whereas authoritarianism, but not dominance, predicted benevolent sexism. The first connection between dominance and hostile sexism link is coherent with the emphasis that Pratto et al. (1994) pointed out of an intergroup hierarchy, because hostile sexism may be placed as supporting a male dominance over women. On the other hand, the link between authoritarianism and benevolent sexism is consistent with Altemeyer’s (1998) emphasis on intragroup tradition since benevolent sexism may serve the function of preserving traditions that, in turn, reinforce gender inequality.

Research Questions

What is the role of conservatism and hierarchical intergroup relations in the gender role ideology and the hostile and benevolent sexism? How do these psychosocial variables relate to the centrality of religion and the political ideology?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the study was to analyse the relationships between authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, gender role ideology, benevolent and hostile sexism, centrality of religion and ideological political self-placement. After that, we analysed the differential contribution of authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and gender role ideology in benevolent and hostile expressions of prejudice towards women.

Research Methods

Participants

Data was collected from 328 university students from Buenos Aires City, between 18 and 40 years old (

Measures

Procedure

Participants were invited to join this study voluntarily and were informed that data provided will be used just for academic and scientific purposes under the Argentinian personal data protection Law Nº25.326.

Analysis

The data of this study was analyzed using the SPSS 20.0 (Lizasoain & Joaristi, 2003) and the EQS 6.1 (Bentler, 2008) software. We performed descriptive analysis for each item and reliability analysis through testing the internal consistency for the overall scale. Finally, we run a path analysis in order to test the predictive effects of right-wing authoritarianism and social dominance orientation on gender role ideology, benevolent and hostile sexism.

Findings

First, we analyzed the correlations between hostile and benevolent sexism, authoritarianism, social dominance, centrality of religion and ideological political self-placement (Table

As can be seen in the diagonal of Table

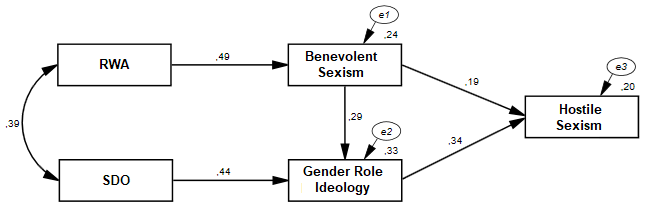

The next step was to test a path analysis with authoritarianism and social dominance as predictive variables of hostile and benevolent sexism, being the relationships between social dominance and hostile sexism mediated by gender role ideology (Figure

SEM fit indexes were adequate (X2(gl) = 20,615 (4); CFI = .960; Δ2 = .960; SRMR = .048), realizing that the proposed theoretical model fits the data collected.

Conclusion

The first purpose of this study was to analyse the correlations between authoritarianism, social dominance orientation, gender role ideology, benevolent and hostile sexism, centrality of religion and ideological political self-placement. After that, we tested the differential contribution of authoritarianism, social dominance orientation and gender role ideology in benevolent and hostile expressions of prejudice towards women.

Regarding the first purpose, all correlations were significant. Authoritarianism and social dominance were positively related to both forms of sexism. Nonetheless, as the literature suggests (Christopher & Mull, 2006), authoritarianism was more strongly related to benevolent sexism and social dominance with hostile sexism. Moreover, as expected (Fiske, 2017), due to the conservative characteristics of the authoritarians, a greater association was found between this variable and the centrality of religion. However, despite previous studies suggested that centrality of religion has been found to predict only benevolent sexism (Maltby, Hall, & Anderson, 2010), in our research both forms of sexism were related to religion, being the hostile sexism the most strongly related. These findings may suggest that maybe, as well as in the study developed in Turkey (Taşdemir & Sakallı-Uğurlu, 2010) comparing catholics with islamists, our results could be explained by the specific religion of the participants. Moreover, as well as in previous studies (Christopher & Mull, 2006), we found that more conservative political orientation is also related to sexism, reinforcing the idea that for these people women should be limited to certain traditional gender roles.

When testing the second purpose of our study through SEM we found that, as hypothesized, authoritarianism and social dominance were predictive variables of hostile and benevolent sexism, being the relationships between dominance and hostile sexism significantly mediated by gender role ideology. This model supports the notion of sexism based on traditional gender roles ideologies that reinforces status and power differences between groups. These findings have truly negative consequences, because according with Pratto et al. (1994) and Fiske (2017), this is the way in which society legitimizes negative representations that elicit higher levels of prejudice and discrimination toward women considered as a low status group targeted for domination (Kilianski, 2003).

For future research in the Argentinean context, we suggest a more in-depth analysis of religious orientation, as well as to analyse sex differences in the theoretical model proposed. We also recommend to enlarge the reference sample in order to achieve greater generalizability and representativeness of the results. To this end, it would be appropriate to increase the sample size and to work with the general population.

References

- Agarwal, B. (2018). The challenge of gender inequality. Economia Política, 35(1), 3-12.

- Altemeyer, B. (1981). Right-Wing Authoritarianism. Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press.

- Altemeyer, B. (1998). The other “authoritarian personality”. In M. Zanna (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology (pp. 47–92). San Diego, CA: Academic.

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Barrancos, D., Guy, D., & Valobra, A. (2014). Moralidades y comportamientos sexuales. Bs. As.: Biblos.

- Bentler, P. M. (2008). EQS 6 structural equations program manual. Encino: Multivariate Software.

- Camou, M., Maubrigades, R., & Thorp, S. (2016). Gender Inequalities and Development in Latin America During the Twentieth Century. Oxford: Routledge.

- Cárdenas, M., & Barrientos, J. (2008). The Attitudes Towards Lesbians and Gay Men Scale (ATLG): Adaptation and Testing the Reliability and Validity in Chile. Journal of Sex Research, 45(2), 140-149.

- Christopher, A. N., & Mull, M. S. (2006). Conservative ideology and ambivalent sexism. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(2), 223-230.

- Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación. (2017). Datos estadísticos del Poder Judicial sobre Femicidios. Retrieved from:https://www.csjn.gov.ar/omrecopilacion/docs/informefemicidios2017.pdf

- Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2010). Personality, Ideology, Prejudice, and Politics: A Dual-Process Motivational Model. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1861-1894.

- Etchezahar, E. (2012). Las dimensiones del autoritarismo: Análisis de la escala de autoritarismo del ala de derechas (RWA) en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires. Revista Psicología Política, 12(25), 591-603.

- Etchezahar, E., Prado-Gascó, V., Jaume, L., & Brussino, S. (2014). Validación argentina de la escala de Orientación a la Dominancia Social (SDO). Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 46(1), 35-43.

- Fiske, S. T. (2017). Prejudices in cultural contexts: shared stereotypes (gender, age) versus variable stereotypes (race, ethnicity, religion). Perspectives on psychological science, 12(5), 791-799.

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (1996). The Ambivalent Sexism Inventory: Differentiating hostile and benevolent sexism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(3), 491-512.

- Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56(2), 109-118.

- Kilianski, S. E. (2003). Explaining heterosexual men’s attitudes towards women and gay men: The theory of exclusively masculine identity. Psychology of Men and Masculinity, 4(1), 37-56.

- Lameiras-Fernández, M. L., Lopez, W. L., Rodríguez-Castro, Y., Dávila, M. L., Lee, T., Fiske, S., Glick, P., & Chen, Z. (2010). Ambivalent Sexism in Close Relationships: (Hostile) Power and (Benevolent) Romance Shape Relationship Ideals. Sex Roles, 62(7), 583-601.

- Lizasoain, L., & Joaristi, L. (2003). Gestión y análisis de datos con SPSS. Madrid: ITES-PARANINFO.

- Lupano Perugini, M. L., & Castro Solano, A. (2011). Teorías implícitas del liderazgo masculino y femenino según ámbito de desempeño. Ciencias Psicológicas, 5(2), 139-150.

- Maltby, E., Hall, L., & Anderson, T. (2012). Sanctified Sexism: Discrimination in Religious Organizations. UK: Praeger.

- Moya, M., Expósito, F., & Padilla, J. L. (2006). Revisión de las propiedades psicométricas de las versiones larga y reducida de la escala sobre ideología de género. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 6(3), 709-727.

- Moya, M., Navas, L., & Gómez Berrocal, C. (1991). Escala sobre la ideología del rol sexual. Actas del Congreso de Psicología Social de Santiago de Compostela, 554-566.

- Nadler, E. B., & Morrow, W. R. (1959). Authoritarian attitudes toward women and their correlates. Journal of Social Psychology, 49(1), 113-123.

- Observatorio Nacional de Violencia contra las Mujeres. (2017). Violencia contra las mujeres y salud: Malestar, medicalización y consume de sustancias psicoactivas. Retrieved from:https://www.argentina.gob.ar/sites/default/files/informeviolenciamedicalizacionconsumofinal.pdf

- Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L. M., & Malle, B. F. (1994). Social Dominance Orientation: A Personality Variable Predicting Social and Political Attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(4), 741-763.

- Reyes Aguinaga, H. (1998). Relaciones de género y machismo. Entre el estereotipo y la realidad. Iconos, 5, 84-94.

- Rodríguez, M., Sabucedo, J. M., & Costa, M. (1993). Factores motivacionales y psicosociales asociados a distintos tipos de acción política. Psicología Política, 7, 19-38.

- Rudman, L. A., & Glick, P. (2008). The Social Psychology of Gender: How Power and Intimacy Shape Gender Relations. New York: Guilford Press.

- Taşdemir, N., & Sakalli-Uğurlu, N. (2010). The Relationships between Ambivalent Sexism and Religiosity among Turkish University Students. Sex Roles, 62(7-8), 420-426.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Ungaretti, J., Etchezahar, E., Albalá, M., & Maldonado, A. (2019). Hostile And Benevolent Sexism: The Role Of Conservatism And Intergroup Hierarchy. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 219-227). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.28