Abstract

Bullying is currently considered a serious problem that can threaten the social and emotional development of youth. The present study has carried out a systematic review of the effectiveness of antibullying programs applied in Spanish schools, all of which aimed to prevent and/or reduce bullying behaviors in their different forms. Certain international systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs have included a few programs applied in Spain, but there is no study that compiles and integrates up-to-date information on anti-bullying programs applied and assessed in Spain. In this systematic review, an exhaustive search of the studies published between 1990 and 2018, in Spanish or English, was performed in several databases, meta-searches, as well as in other formal and informal relevant sources of information, resulting in 13 studios which met the established inclusion criteria. The results, based on data from approximately 4600 students, showed mostly positive evaluations of the effectiveness of the anti-bullying programs. These results are discussed, however, in relation to the difficulty in establishing common patterns of effectiveness due to the wide variation in aspects of programs implementation, methodological characteristics of the studies, as well as the different procedures to assess bullying.

Keywords: Bullyingcyberbullyingschool-based anti-bullying programssystematic review

Introduction

In most developed countries, bullying is currently considered a serious problem that can threaten the social and emotional development of youth. Experiences at school occur during crucial developmental periods of life, influencing the adolescent’s psychological adjustment and physical and emotional wellbeing, both present and future. Bullying is considered a type of violence exercised by young people in the school environment, which is characterized by the following core aspects: the bully’s intention to cause harm, the repetition of intimidating behaviours over time, as well as a disproportion of power between aggressor and victim; being the imbalance of power and the mistreat maintained over time the distinctive aspects of bullying against other types of violence among minors (Rodkin, Espelage, & Hanish, 2015). Since the initial studies of bullying first appeared, different forms of bullying have been identified, whereby we may categorize bullying behaviours into four types: physical, verbal, social/relational and cyberbullying. Physical bullying is characterized by causing direct physical harm, and includes behaviours like hitting, pushing, and so on. Verbal bullying occurs when humiliations, intimidation or defamation are made on the victim, through insults and threats. Social or relational bullying involves spreading rumours for the purpose of socially excluding the victim; is usually subtler and is carried out with the intent to damage the victim’s social relationships. Finally, cyberbullying is characterized by the use of social networks and Internet to spread rumours, with the intent to intimidate or damage the victim’s cyber-image. These different forms of practicing bullying are directly related to the contexts in which they take place. Bullying takes place principally at school facilities; but it also happens during after-school activities, and if using a mobile device, from home or from anywhere, but basically as a result of the school relationships (Calmaestra et al., 2016). As for the prevalence of bullying, studies carried out in different countries have documented widely varying rates. For example, in a broad study carried out by the World Health Organization (Currie et al., 2012), in which children between 10 and 15 years old, across 43 countries (from Europe, the U.S. and Canada) were assessed in bullying and victimization, the general bullying rates fell between 1% and 36%, and rates of victimization between 2% and 32%, according to the country. These between-country differences in prevalence rates may point to cultural factors about the acceptability of bullying within society, but also to differences in the way that bullying is assessed, as well as to the influence of other important variables, such as age and gender, that not always are considered (Hymel & Swearer, 2015). The systematic review carried out by García-García, Ortega, De la Fuente, Zaldívar, & Gil-Fenoy (2017) with Spanish data showed a prevalence rate of 11.5% for bullying in general, and broken down by type, a lower rate for cyberbullying than for “traditional” bullying, which includes the physical, verbal and social/relational.

Problem Statement

In Spain, awareness of the scope and widespread nature of bullying began in the 1990s. Since then, different programs for preventing and reducing bullying have been proposed, both from the public administration and from the schools themselves. However, there has not always been a practice of program assessment, in order to verify their effectiveness, despite the fact that assessment is fundamental for making evidence-based decisions toward improvement. Although some international systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs have included certain programs applied in Spain (Farrington & Ttofi, 2009; Jiménez-Barbero et al, 2016; Tanrikulu, 2018), there is no study that compiles and integrates up-to-date information on anti-bullying programs applied and assessed in Spain.

Research Questions

The main question in this research is to know what results the anti-bullying programs applied and evaluated in Spain have obtained, as well as to know if common elements can be established among the programs that have achieved positive results.

Purpose of the Study

This study seeks to cover this gap of information by offering a systematic review of the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs applied and assessed in Spanish schools, which aimed to prevent and/or reduce school bullying behavior in its different.

Research Methods

Search Criteria and Sources of Information

This systematic review was realized conforming to the requirements of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Statement (Moher et al., 2015). The bibliographic search was executed on the following sources: Proquest Psychology Journal, PsycARTICLES, ISOC, Scopus, Psicodoc, Dialnet, PsycInfo, ISI Web of Science, TESEO (Doctoral dissertations database), specialized conferences, and references indexed in the studies incorporated to this systematic.

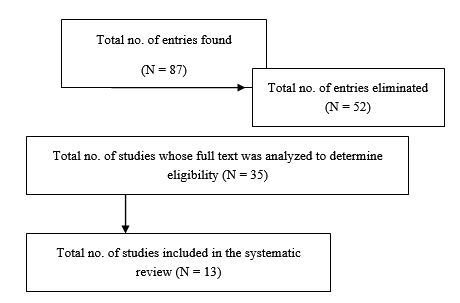

The search strategy and key words used, in English and in Spanish, were: “anti-bullying programs AND Spain”, “intervention/prevention AND bullying/ cyberbullying AND Spain”. The search was not limited by sample size or type of publication in order to reduce publication bias. The search was realized in November 2017 and updated in May 2018, resulting in 87 entries that matched the inclusion criteria, all of which were reduced to 35 after reading abstracts. Subsequently, after reading the full text of these 35 studies, twenty-two of them were eliminated, resulting in a total of thirteen studies included in this review. In Figure

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

This systematic review includes studies that met the following criteria: (1) they offer empirical evidence from assessing a program for prevention of and/or intervention in bullying/cyberbullying; (2) they have been applied in Spanish primary or secondary schools (including compulsory and post-compulsory); (3) they are directed to students, even if teachers or parents are involved; (4) an experimental or quasi-experimental design is used, with pretest-postest assessments, with or without a control group, for the assessment of effectiveness; (5) they must provide basic statistical information based on outcome measures; (6) the study was published between 1990 and 2018, in Spanish or English.

As exclusion criteria: (1) Studies that describe application of a program for prevention and/or intervention in bullying/cyberbullying, but do not present assessment data on outcomes; (2) programs aimed at other types of violence in underage youth (juvenile, within the family, etc.).

Codification of Results and Analysis of the Information

The following information was collected for each of the studies included in this review: (1) Formal identification aspects: authors, year of publication, type of publication, program name. (2) Methodological characteristics: type of research design, follow-up, characteristics of the participants (age, gender), sample size, assessment instruments used, outcome variables, statistical results. (3) Information regarding program implementation: general objective (prevention/intervention), specific objectives, theoretical foundation, components of the program, scope of application, duration and intensity, therapeutic elements, standardization of the program, integrity of the intervention.

Findings

The present study sample contains a total of 13 papers that incorporate a combined total of 4606 students. The mean sample size of the studies was 248, with a standard deviation of 326.6; sample size ranges from a minimum of 23 to a maximum of 910. Regarding sample distribution by educational level, 4 of the 13 studies applied an anti-bullying program only to compulsory secondary students, ages ranging from 12 to 15 years; 3 studies addressed students from primary and secondary school (ages 8 to 15); and another 3 studies included students from compulsory and post-compulsory secondary education (ages 12 to 18). In addition, 2 of the 13 studies were carried out with only primary students (ages 8 to 12 years), and finally, a single study addressed students from all three educational levels, with ages from 8 to 18. Regarding sample distribution by gender, in most studies the distribution is roughly proportional, ranging between 39% and 57%.

Regarding the methodological characteristics of the studies reviewed, the general procedure for evaluating program results was comparative analysis of the different outcome variables as measured in pre- and post-tests, in control groups and in program groups; there were two studies, however, with no control group, and one study where a sociometric analysis was carried out. On the other hand, the outcome variables used for program assessment were as follows: (a) self-report measures collected through standardized questionnaires: bullies, perpetrators and spectators of bullying (5 studies), of cyberbullying (1 study), of bullying and cyberbullying (2 studies); (b) perception of the general social climate at school (3 studies); (c) attitudes toward violence (3 studies); (d) emotional competencies (1 study); (e) direct measures of bullying through recorded observation at school (2 studies). A summary of the main methodological characteristics of the studies’ research designs is shown in Table

As for information collected from these studies about program implementation, the general objective of 7 of the 13 programs was found to be prevention of bullying, while 6 programs are intended for both prevention and for direct intervention in bullying behaviors. Regarding scope of program application, only 5 have a community approach that involves the school in its totality (students, teachers, parents, class and school), 3 programs include both teachers and students, and the remainder address the class or the students. The most ambitious program is the SAVE program, which addresses students as well as teachers and families. The program by Díaz-Aguado, Martínez-Arias, & Martín-Seoane (2004) also actively involves other agents and is novel in its incorporation of volunteers from youth associations, in addition to parents and teachers. The rest are limited to students only (primarily to bullies and victims, but also to spectators).

We regard to the theoretical foundations of the programs, most of them present generic foundations, not specific to any particular model, although reliance on the cognitive-behavioral model or on the theory of social learning can be observed. Programs with a more specific theoretical foundation were the ConRed Program (Del Rey, Casas, & Ortega, 2012) based on the Theory of Normative Social Behavior (Rimal & Real, 2003); the program by Del Barrio et al. (2011), built on the Cowie and Wallace (2000) model; the SAVE Program, based on an ecological perspective and on several specific theoretical models for the different therapeutic components; the program by Filella, Cabello, Pérez-Escoda, & Ros-Morente (2016), based on the Gross (2008) model of intervening in emotional regulation strategies. As for methodological rigor in program application, most of the programs reviewed do not offer information on the integrity of their implementation, with the exception of

Regarding standardization of the programs applied, most of the studies (10) can be considered to contain a sufficiently detailed description of the activities carried out, or they indicate other publications where the program is spelled out in detail. In three studies, however, programs are not standardized, because the intervention is more flexible and more fitted or individualized to the outcomes and needs of the users, most notably in the case of the SAVE program, by Ortega (1997). Another important aspect considered was program length and/or number of sessions. We found much variability, from programs that continued over entire school years, down to one-month program duration.

Conclusion

The present study has carried out a systematic review of the effectiveness of anti-bullying programs applied in Spanish schools, all of which aimed to prevent and/or reduce bullying behaviors in their different forms. From the results obtained, based on data from 13 studies that were included in the systematic review, and incorporating approximately 4600 students, mostly positive evaluations were reported. However, it is difficult to establish any common effectiveness pattern, given that few studies present assessment results, and because of the wide variation in aspects of program implementation and methodological characteristics.

Regarding the former, we note the variability and even absence of information in aspects that are important for understanding program effectiveness, such as the actual degree of program implementation, or the duration and intensity of program application, where we found programs that last entire school years, and programs lasting a single month, and the number of sessions was not always stated. Previous reviews have presented evidence that duration and intensity of a program is positively related to a reduction in school bullying and victimization (Farrington & Ttofi, 2009). On another hand, in relation to the general and specific program objectives, the therapeutic objectives of prevention programs relate more to improvement of the school climate and life together, by trying to improve emotional competencies, empathy, social skills, and so on. When the program had intervention purposes (reducing the number of victims, bullies, and spectators), the therapeutic objectives were more focused on recognizing bullying and effective conflict management. Therapeutic strategies common to all the programs included group dynamics, training in social skills, role-playing, values education in nonviolence, and use of educational videos.

With respect to the methodological characteristics of the programs evaluated, one important aspect that varied greatly were the assessment instruments used to measure outcomes, many of them developed by the program authors themselves, making it difficult to compare results, even though a majority of these did include reliability measures. Similarly, there was great variation in the study sample sizes, with number of participants ranging from 23 to 910; however, there was no direct relationship between sample size and the results obtained. The only aspect where one can find a relationship with results obtained was the choice of outcome variables used to evaluate the programs. The two studies that used direct measures of bullying, through school observation records, were the ones that did not find statistically significant reductions in the number of conflicts or of bullying behaviors, while in 90% of the studies that used self-report measures to collect measurements of bullying, statistically significant improvements were reported, with low to moderate effect sizes. Finally, we note that the assessment designs used were not strong from the viewpoint of methodological quality, given that only one of the studies used a pretest-postest design with a randomized control group. This is an aspect for improvement in future studies, and one that will have positive repercussions on the internal validity of assessment results, given that alternative explanations for improvement (other than the program itself) may be more safely ruled out.

Acknowledgments

This research has been supported by the Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (Spain) [DER2014-58084-R]

References

- Calmaestra, J., Escorial, A., García, P., Moral, C., Perazzo, C., & Ubrich, T. (2016). Yo a eso no juego. [I don’t play that game.] Bullying y Ciberbullying en la infancia. Milan: Save the Children. Legal deposit: M-4030-2016.

- Cowie, H., & Wallace, P. (2000). Peer support in action: from bystanding to standing by. London: SAGE.

- Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., de Looze, M., Roberts, C., Samdal, O., Smith, O., & Barnekow, V. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: international report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen, WHO Regional Office for Europe (Health Policy for Children and Adolescents, No. 6).

- Del Barrio, C., Barrios, Á., Granizo, L., Van der Meulen, K., Andrés, S., & Gutiérrez, H. (2011). Contribuyendo al bienestar emocional de los compañeros: evaluación del Programa Compañeros Ayudantes en un instituto madrileño. European Journal of Education and Psychology, 4(1), 5-17.

- Del Rey, R., Casas, J.A., & Ortega, R. (2012). El programa ConRed, una práctica basada en la evidencia. Comunicar, 39, 129-138.

- Díaz-Aguado, M.J., Martínez-Arias, R., & Martín-Seoane, G. (2004). Estudio experimental sobre el programa de prevención de la violencia entre iguales en la escuela y en el ocio. In M.J. Díaz-Aguado et al., (Eds.) Prevención de la violencia y lucha contra la exclusión desde la adolescencia. Vol. 2: Programa de intervención y estudio experimental. Madrid: Instituto de la Juventud. Disponible también en: mtas.es/injuve/novedades/prevenciónviolencia.htm

- Farrington, D. P., & Ttofi, M. M. (2009). School-Based Programs to Reduce Bullying and Victimization. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 2009, 6.

- Filella, G., Cabello, E., Pérez-Escoda, N, & Ros-Morente, A. (2016). Evaluación del programa de Educación Emocional “Happy 8-12” para la resolución asertiva de los conflictos entre iguales. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 14(3), 582-601.

- Garaigordobil, M., & Martínez-Valderrey, V. (2014). Effect of Cyberprogram 2.0 on reducing victimization and improving social competence in adolescence. Revista de Psicodidáctica / Journal of Psychodidactics, 19(2), 289-305.

- García-García, J., Ortega, E., De la Fuente, L., Zaldívar, F., & Gil-Fenoy, M.J. (2017). Systematic Review of the Prevalence of School Violence in Spain. Procedia- Social and Behavioral Sciences 237, 125-129.

- Gross, J. J. (2008). Emotion regulation. Handbook of emotions, 3(3), 497-513.

- Hymel, S., & Swearer, S.M. (2015). Four Decades of Research on School Bullying. An Introduction. American Psychologist, 70(4), 293-299.

- Jiménez-Barbero, J.A., Ruiz-Hernández, J.A., Llor-Zaragoza, L., Pérez-García, M., & Llor-Esteban, B. (2016). Effectiveness of anti-bullying school programs: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 165-175.

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L.A., & PRISMA-P Group (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1).

- Ortega, R. (1997). Proyecto Sevilla Anti-violencia Escolar. Un modelo de intervención preventiva contra los malos tratos entre iguales. Revista de Educación, 313, 143-160.

- Rimal, R. N., & Real, K. (2003). Understanding the influence of perceived norms on behaviours. Communication Theory, 13(2), 184-203.

- Rodkin, P. C., Espelage, D. L., & Hanish, L. D. (2015). A relational framework for understanding bullying: Developmental antecedents and outcomes. American Psychologist, 70(4), 311-321.

- Tanrikulu, I. (2018). Cyberbullying prevention and intervention programs in schools: A systematic review. School Psychology International, 39(1), 74-91.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

García, J., De la Fuente, L., Zaldívar, F., & Ortega, E. (2019). Effectiveness Of School-Based Anti-Bullying Programs In Spain: A Systematic Review. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 211-218). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.27