Abstract

Refugee women are a vulnerable group, due to their life stories, which leads to these aspects being the first to be intervened by the different institutions and NGOs that work with these women. The objective of this paper is to analyze the interventions made, from the perspective of maintaining the culture and language of origin. For this, the M-IBQ Scale was used in a sample of 264 women, of a total of 1910 people relocated and resettled in Spain, out of which 650 are women. This scale analyses socio-demographic variables of ethnicity, geographic residence, age, and length of time in Spain, and contains five subscales: “Speak Native Language”, “Speak English Language”, “Enjoy Native Activities”, “Enjoy American Activities”, and “Desired Ideal Culture”. The scale was sent to the NGOs, in which the women are attended and it was passed by the professionals and volunteers of the same, needing, for this, a period of 9 months. The results of the analysis of the data show that, although refugee women are adequately cared for, in none of the cases has intervention in the maintenance of the language and culture of origin, producing a process of acculturation.

Keywords: Acculturationrefugee

Introduction

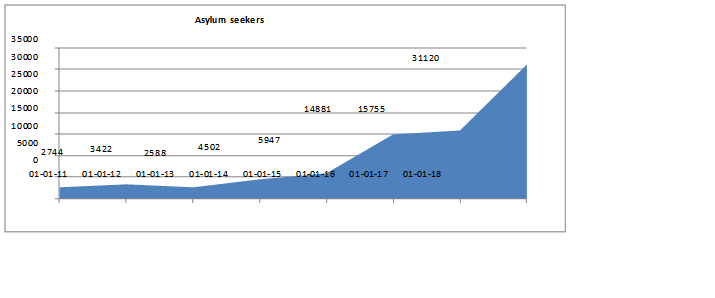

The vast majority of resettled refugees to the Spain come from Syria, Somalia and Afghanistan (CEAR, 2017). Most of the refugees reside in Barcelona, Madrid, Valencia, Sant Feliú, A Coruña, Palma, Alicante, and Getafe. The rest of the Spanish have resettled only a few people and, in many cases, none of them. In 2017, Spain received 31,120 asylum applications (Figure

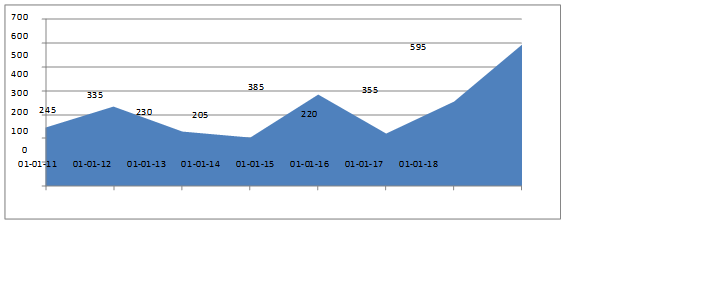

From the applications that have been submitted to the Spanish State, 595 achieved refugee status (Figure

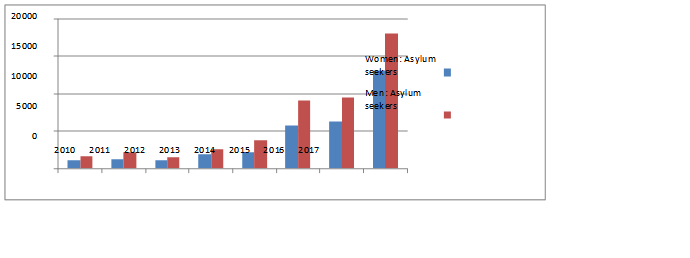

About the group of women, since 2010, almost 32,542 have applied for asylum in Spain and, as it is shown in the Figure

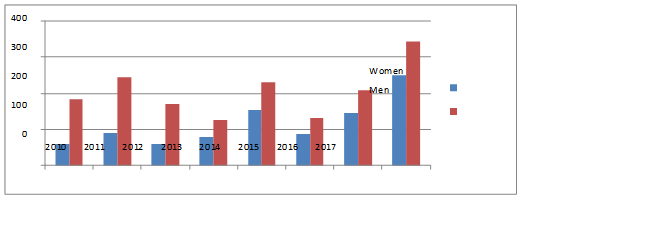

According the Figure

According to Johnson-Agbakwu, Flynn, Asiedu, Hedberg, & Breitkopf (2016):

Relocating and adjusting to vastly different environments require an adaptive process for both the refugees and the accepting communities. Uncertainties surrounding differences in cultures can result in mistrust and discriminatory practices. The psychological stressful factors and the unfavorable results, due to the perceived discrimination, have to be taken into account so it is important to understand the acculturation experiences of this population.

Acculturation was described by Berry (2005) as "the dual process of cultural and psychological change that takes place as a result of contact between two or more cultural groups and their individual members" (p. 698). It is necessary to declare that, despite the fact that Berry is the one of the contributors of this definition, he is really closer to the classic Redfield, Linton, & Herskovits (1936), since Berry would be in a contrary perspective, as defender of the classic model of acculturation of four squares, where staying in the society of origin and adopting or participating in the receiving society it is estimate as orthogonal. The historical views of acculturation have established one-dimension process where there is an inverse linear relationship between the participation of a person with the original culture and the host culture (Szapocznik, Kurtines & Fernández, 1980). However, other authors (Beck, Froman, & Bernal, 2005) argue that the acculturation does not follow a linear process and that it often does not lead to the loss of cultural identity, and that could be called biculturalism (Arjona, Checa, & Belmente, 2011). Undoubtedly, we should not forget the Relative Acculturation Extended Model (RAEM) of Navas, Rojas, Pumares, Lozano, & Cuadrado (2010) who introduced the different situations of the ideal and real in the acculturation process.

Either way, research is needed to analyze the psychological attributes of participation in both cultures simultaneously as other authors have done in other contexts (Pan, Wong, Chan, & Chan, 2008; Shim & Schwartz, 2008; Norris, Ford, & Bova, 1996; Marin, Sabogal, Marin, Otero-Sabogal, & Perez-Stable, 1987; Marin & Gamba, 1996; Cuellar, Arnold, & Maldonado, 1995; Cruz, Marshall, Bowling, & Villaveces, 2008; Barona & Miller, 1994) and more specifically research is needed to analyze the experiences of women, specifically refugee women, as we have only found the information provided by Johnson-Agbakwu et al. (2016), which makes an adaptation of the M-IBQ scale for refugee women.

Thus, the aim of this paper is to analyze the interventions made from the perspective of maintaining the culture and language of origin of refugee women in Spain.

Research Methods

The research is carried out in the quantitative approach, using an analytical methodology and an analytical method of investigation, and data are collected and exposed. These data are happening in the context and with the population analyzed, and in the future, an intervention in accordance with the results obtained will be performed.

The research design used is descriptive and cross-sectional, since the information has been collected at a specific moment, that the people participating in the research, are living.

During the research process, the first step we took was to contact the associations which are serving refugee women in the Spanish context (Plataforma Somos Migrantes, Red Cross, Nombre de la Ciudad Acoge, Spanish Commission for Refugee Assistance (CEAR), Save The Children, Asociación Comisión Católica Española de Migraciones (Accem), AAsociación de Apoyo al Pueblo Sirio de Andalucía, Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado, among others) to consult them about the profile of refugee women and about the option of the translation of the Scale. We were told that the best option was to send it in Spanish and that they would be responsible for making the translation to each woman, given the variety of mother tongues that they had and so we did.

Population, sampling and sample

After contacting the organizations, we were able to estimate that there are 650 refugee women with approved asylum documents who currently live in Spain. The great majority of them, 598, are treated in some of the organizations contacted, who asked these women about their availability to participate in the scale. Finally, after the incidental sampling used, only those who wished to take part participated and so we had a total of 302 women. However, some of them due to various difficulties did not finish the scale and, therefore, the sample was composed by a total of 264 refugee women.

Data was collected between June 2017 and March 2018, in a period of 9 months, as in August data was not collected, due to the decrease of volunteers, who fulfilled the scale with the participants as well as the professionals.

Data collection instruments

The instrument used was the M-IBQ scale, which consists of 33 questions that explore different areas of acculturation within 5 research areas: demography, acculturation, health history and desired health knowledge, preferred health and healthcare providers and modalities of Education.

The scales were administered orally in face-to-face meetings with professionals and volunteers, trained by the team, in a specific way, within the presence in many cases of people trained in the language of choice of the participant: English, Syrian or Afghan, in which the woman is given three options, which are identified with three types of faces, thus indicating: never, sometimes, always.

This instrument presents an α level of less than 0.05 of statistical significance. In general, it has 5 different underlying factors that are internally consistent within each respective subscale, thus preserving its original factor.

Results

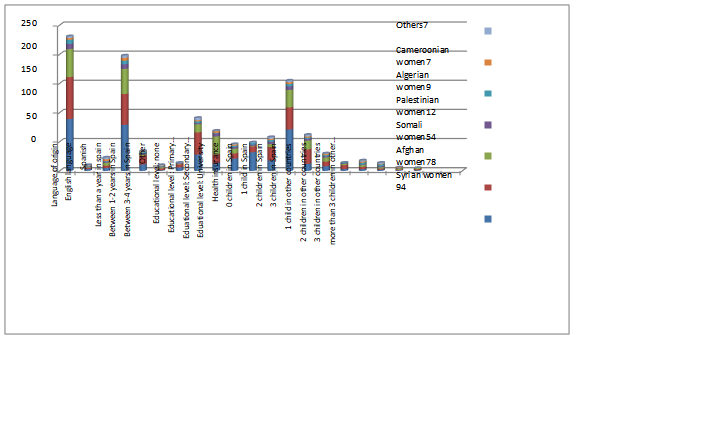

After collecting the data, the 264 participating refugee women present the characteristics shown in Figure

Regarding the results obtained, in the different subscales (Use of the native language", "Use of Spanish", "Enjoy native activities", "Enjoy Spanish activities" and "Desired ideal culture"), we can see them, represented, in Table

Conclusion

Through this study, we have been able to verify that various Organizations in Spain support many women, both asylum seekers and refugees, providing them with significant assistance. Particularly, the refugee women who have participated to our research are highly satisfied by the kind of assistance they receive in such. Organizations (Figure

Regarding the data collected by the five acculturative subscales, we could say that all refugee women prefer to use their native language and they do not want to lose neither any aspect of their identity nor to change their culture. Moreover, they are not seemed to be willing to introduce to their customs any Spanish habits, as it is shown in the research carried out by Johnson-Agbakwu et al. (2016). The initial investigation holds promise that the M-BIQ may be generalizable for the Central and Est African refugees, regardless of the geographic resettlement or period of time of residence in Spain.

In conclusion, we can say that in refugee women in Spain are not characterized by a bicultural identity, but by mono-culturalism, which is reflected in their culture of origin and not in the Spanish culture. Moreover, it is shown that these women are actively preserving their national culture via the exclusion of external (in this case Spanish) influences, so we cannot talk about acculturation, because there is no intention from refugee women to incorporate to their culture, Spanish elements.

In the future, we are planning to make a progress of the present research, since we should bear in mind that the majority of the women who participated in the survey, do not speak Spanish and they are in Spain for a long time, key factors in the processes of acculturation

References

- Arjona, A. Checa, F., & Belmonte, T. (2011). Biculturalismo y segundas generaciones: Integración social, escuela y bilingüismo. Barcelona, Icaria.

- Barona, A., & Miller, J. A. (1994). Short acculturation scale for Hispanic youth (SASH-Y): A preliminary report. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences, 16(2), 155-162.

- Beck, C.T., Froman, R.D., & Bernal, H. (2005). Acculturation level and post-partum depression in Hispanic mothers. MCN: The American Journal of Maternal/Child Nursing, 30, 299–304.

- Berry, J. W. (2005). Acculturation: living successfully in two cultures. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 29, 697–712.

- CEAR (2017). Informe 2017 de la Comisión Española de Ayuda al Refugiado. Retrieved from: https://www.cear.es/wp-content/uploads/2017/06/Informe-Anual-CEAR-2017.pdf

- CEAR (2018). Más que cifras. http://www.masquecifras.org/

- Cruz, T.H., Marshall, S.W., Bowling, J.M., & Villaveces, A. (2008). The validity of a proxy acculturation scale among U.S. Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci. 30, 425–446.

- Cuellar, I., Arnold, B., & Maldonado, R. (1995). Acculturation rating scale for Mexican Americans-II: a revision of the original ARSMA scale. Hisp J Behav Sci, 17, 275–304.

- Marin, G., & Gamba, R. (1996). A new measurement of acculturation for Hispanics: the bidimensional acculturation scale for Hispanics (BAS) Hisp J Behav Sci, 18, 297–316.

- Johnson-Agbakwu, C. E., Flynn, P., Asiedu, G. B., Hedberg, E., & Breitkopf, C. R. (2016). Adaptation of an Acculturation Scale for African Refugee Women. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health / Center for Minority Public Health, 18 (1), 252–262. http://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-014-9998-6

- Marin, G., Sabogal, F., Marin, B.V., Otero-Sabogal, R., & Perez-Stable, E.J. (1987). Development of a short acculturation scale for Hispanics. Hisp J Behav Sci, 9, 183–205.

- Navas, M., Rojas, A., Pumares, P., Lozano, O., & Cuadrado, I. (2010). Perfiles de aculturación según el Modelo Ampliado de Aculturación Relativa: autóctonos, inmigrantes rumanos y ecuatorianos. Revista de Psicología Social, 25(3), 295-312.

- Norris, A.E., Ford. K., & Bova, C.A. (1996). Psychometrics of a brief acculturation scale for Hispanics in a probability sample of urban Hispanic adolescents and young adults. Hisp J Behav Sci, 18, 29–38.

- Pan, J.Y., Wong, D., Chan, K.S., & Chan, C. (2008). Development and validation of the Chinese making sense of adversity scale: acculturative stressors as an example. Res Social Work Pract, 18, 475–486.

- Redfield, R, Linton, R., & Herskovits, M. J. (1936). Memorándum forma. The Study of Acculturation. American anthropologist, 38 (1), 149-152.

- Shim, Y.R., & Schwartz, R.C. (2008). Degree of acculturation and adherence to Asian values as correlates of psychological distress among Korean immigrants. J Mental Health, 17, 607–617.

- Szapocznik, J., Kurtines, W.M., & Fernandez, T (1980). Bicultural involvement and adjustment in Hispanic-American youths. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 4, 353–365.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Angelidou, G., Aguaded-Ramírez, E. M., Parra-González, E., & Parra-González, E. (2019). Analysis Of Process Of Adaptation And Acculturation Of Refugee Women In Spain. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 133-140). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.17