Abstract

This paper reports on research in the Colombian municipalities of Alpujarra Tolima, Neira Caldas, Marulanda Caldas, Geneva Valle, Zarzal Valle, Quebrada Nueva and Aranzazu Caldas that explored the characteristics of pastoral care in communities in rural areas. Two key research findings are presented. The first is that some specific features that characterize contemporary society, such as globalization and globalism, run counter to the rural identity, and specifically to the exercise of the community activities of accompaniment, education and evangelizing as they are guided by the pastoral care of the Roman Catholic Church. The second finding comes from a study of how the social thought of the Church, which in principle underpins its pastoral activity, has led to the development of arguments that establish a critique of the most visible elements of contemporary society, resulting to some extent in the promotion of the identity of rural people.In other words, this paper seeks to support the hypothesis that, in the context of the cases studied, contemporary society represents a set of complex challenges that extends even to the structural disarticulation of rural cultural identity as well as the very character of the social thought of the Church.

Keywords: Hermeneuticspastoral carerural identitysocial thought of the Churchsociology

Introduction

This article aims to present some of the results obtained within a doctoral research study, using case studies, in order, first, to explore those practices developed by the Roman Catholic Church through pastoral care in Colombian rural municipalities, and, second, to review the major objective characteristics that make up what is called contemporary society or the market society. The aim is to uncover the contradictions that emerge between the identified Catholic features of rural culture and the market society, recognizing that the latter is the sociological expression that defines most of today’s (urban) societies and therefore imposes various challenges for rural identities that become manifest in pastoral practice.

It is necessary to investigate the current main features of the social thought of the Church, since not only do these display the most objective discursive position of all Christian social practice, but also it is true, as Rivas Gutierrez (1988) would affirm, that a correct appraisal of thought (doctrine) supposes a social hermeneutics that takes into account all its expressions, placing each text in its historical and cultural context. That thought is to be found in the extensive Vatican documents that are analysed in the investigation, bearing in mind the context of the municipalities of Alpujarra Tolima, Neira Caldas, Marulanda Caldas, Geneva Valle, Zarzal Valle, Quebrada Nueva and Aranzazu Caldas. In this article, reference will be made to the development of a formal hermeneutics applied in the encyclical Laudato siʹ, which contains the most up to date message that the Church presents to its worldwide community.

Problem Statement

Cultural identity and background characteristics of the rural areas

The population of the Colombian countryside lives in marked poverty that stems from a problem of land ownership: according to statistics from the National Administrative Department of Statistics (2014), 0.4% of owners own 46% of the land, the Gini coefficient for land is higher than 0.85, and, of the 42.3 million hectares used in agriculture, 80% (33.8 million hectares) is devoted to pasture for cattle and 20% (8.5 million) is arable land. Furthermore, of those 8.5 million arable hectares, 7.1 million are devoted to the agro-industrial cultivation of coffee, palm and sugar cane. The remainder, 1.4 million hectares, is devoted to agriculture for domestic consumption, and on this land 5 million farmers produce 43% of the food consumed in Colombia. Elsewhere, DANE has reported that in scattered and remote rural areas, informal work accounts for 90% of farmers’ income, a figure that correlates with the average poverty level in rural areas of 53%. In addition, and set in this context of generally inequitable and impoverished rural areas, one fact that justifies the analysis of rural cultural identity from the viewpoint of pastoral practice is that, according to the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (2017), Colombia’s major denominations are Catholicism, at 87.3%, Evangelical Protestantism at 11.5%, and other denominations including clusters of members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

This enables us to understand that the development of the rural cultural identity in Colombia is objectively marked by a context of poverty and of difficulties in developing the workforce and therefore of collecting revenue, which leads to the Catholic Church becoming an actor of fundamental importance that sets social and institutional expectations for how the population behaves and lives in that context.

Incompatibility of contemporary society with rural culture

To examine the objective characteristics of contemporary society, Bauman (2006) calls for a different phenomenon that is established among critics of modern society: the fetishism of subjectivity. So, what remains hidden is the relationship of sale behind the construction of such subjectivity, the constant exchange of ad hoc identities that allows the culture of consumerism: I buy, therefore I am, as a subject. I buy therefore I am is the manifestation of the objective behaviour of today’s society, and hence it would not be a mistake to label this sociologically as a market society, because if the consumerist phenomenon is a characteristic feature of contemporary society then in this type of society there is no room for dissent or protest, as the resource to dismantle any resistance or rebellion is to present what is actually a new obligation (Lara & Colin, 2007, 214-215).

Accordingly, it is feasible to view the concept ‘unnecessary requirements’ set out by Pope Francis (2015) in Laudato si', as another characteristic of contemporary society. From a sociological aspect this could become deeper, since: ‘These needs have content and social function, determined by external powers over which the individual has no control; development and satisfaction of these needs is heteronomous’ (Marcuse, 1993, p.35). The criticism Francis (2015) developed in Laudato si' is not logically disconnected from the observation that critical theory is applied to the social controls that require the overwhelming need to produce and consume waste. According to Marcuse (1993), waste is a false necessity that drives at the same time an alienated work whose function is to make possible the waste, then, would not it be valid to question the reason that allows so many individuals to feel comfortable in this type of work? In contemporary society (in the case of Colombia), according to a World Bank (2016), 76.7% of the population is located in urban areas. Individuals in cities, as stated by Marcuse (1993), are recognized by their goods, and are linked to society by producing new needs and exacerbating consumption. Therefore,

‘Negative globalization’ is understood as the highly selective globalization of trade and capital, monitoring and information, coercion and armaments, crime and terrorism ... all items currently spurn territorial sovereignty and not respect any state border (Bauman, 2006, p.126).

Under Bauman’s conceptualization, the expected appearance of what is called ‘negative’ emerges. Why is it negative? Baeza (2006) says that the negative can be understood conceptually and rethought in terms of globalism and becomes established not negatively but positively in the cultural life of contemporary society.

In short, the poverty and inequality of the Colombian agrarian context are part of the peasant culture and even contribute to the construction of identity. Likewise, rural areas end up configuring scenarios apparently impervious to consumerism because are still not configured as authentic market societies. However, the precursors of inequality and poverty that lie in complex issues such as large estate, the boost that agro-industry It gives the idea of converting peasants into entrepreneurs, they are configured as phenomena that seek in the midst of an environment of globalism, hegemonize and therefore address the trends of identity in rurality.

The role of the Church and rural identity

The very nature of the Church leads to social tradition. There have been several descriptions of this tradition of social justice, especially since the publication of the encyclical of Pope Leon XIII, Rerum Novarum, in 1891. Common to these descriptions have been two important pillars of the tradition of social thought: the dignity of the human being, and the common good.

These are not really two different principles, as they are closely related. One of the main concerns of the Catholic tradition has been the dignity of the human person who is created in the image of God. However, this dignity cannot be understood in a completely individualistic sense. Recognizing that God is Trinity, it is also recognized that the human image of God is necessarily communal and relational. According to the encyclicals Gaudium et spes and Mater et Magistra 26 and 65, people flourish only in community. Therefore, in the Catholic tradition, there is a strong interdependence between human dignity and the common good. The dignity of the person is nourished by respect for the common good, which in turn is understood in terms of individuals, and social groups have access to their own fulfilment.

Therefore, there is a close relationship between the Catholic social tradition and the understanding of the Church that emphasizes communion and a call to conversion and transformation in the light of the kingdom of God. If this ecclesiological context has any relevance for Catholic social teaching, it is mainly in the framework of rural society, because in rural society the individual finds his or her significance individually through the practice of consumption, but must do so through the community, which, as is explained above, is the essential social character of the Church. Pope Benedict XVI (2009) made it clear that Catholic social teaching is an expression not only of justice but also of charity. Charity rests on a fundamental substrate: poverty, inequality, neglect, etc. The social work of the Church takes place in communities, on the basis of these theological principles, and is expressed in pastoral practice. It is in communities, where the consumer practices are not exacerbated or show sufficient strength, the scenario where the pastoral practice of the Church probably plays a crucial complementary role in shaping the identity of the rural community.

Research Questions

What approaches of the contemporary social thought of the Church (as laid out in the text Laudato si') identify the characteristics of contemporary society as challenges to pastoral practice in rural areas?

To what extent is rural cultural identity at risk of being homogenized within the market society?

Purpose of the Study

In the context of the problem described, the overall objective of this research is to describe the relationship between pastoral and social activities in Alpujarra Tolima, Neira Caldas, Marulanda Caldas, Valle de Ginebra, Zarzal Valle, Quebrada Nueva and Aranzazu Caldas according to the analysis categories present in the encyclical text Laudato si', in order to establish which social challenges are being faced by typical rural communities, as well as the social practice of the Church.

It was necessary then to develop a formal and sociocultural hermeneutic analysis of Laudato si' encyclical, to establish the analytical categories, as well as to characterize the social and pastoral community action in Alpujarra Tolima, Neira Caldas, Marulanda Caldas, Valle de Ginebra, Zarzal Valle, Quebrada Nueva and Aranzazu Caldas.

Research Methods

Hermeneutics is defined as:

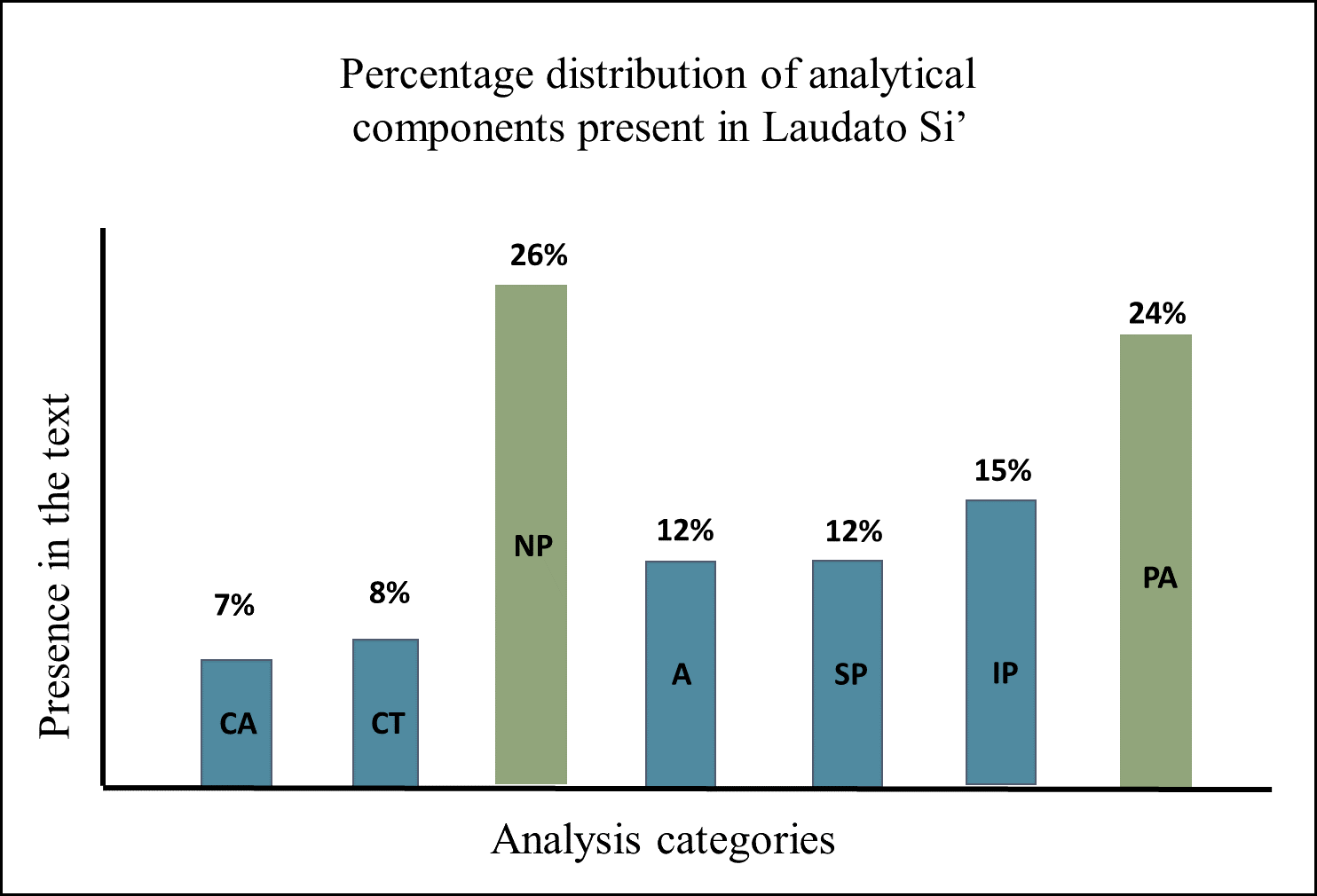

According to this definition it should be recalled that when hermeneutics is used as a comprehensive method, a number of authors who have deepened our understanding of the term should be kept in mind, among them Heidegger, Gadamer, Ricoeur and Habermas. According to Gadamer (2000), ‘the hermeneutical rule is to understand everything from the individual and the individual from the whole. It is a rule that comes from the old rhetoric and modern hermeneutics has taken the art of speaking to the art of understanding’ (p.182). For this reason, a semi-structured interview method was used with subjects who were linked to the pastoral work that takes place in the municipalities visited. In addition, a formal and sociocultural hermeneutic text analysis was developed for Laudato si', from which emerged a trend that can be called categories of analysis; it is better not to consider this trend as having been ‘created’, but to state that what emerged were the most significant interpretive ideas that run through Francis’s text. Subsequently, a systematization of these trends was developed to discover the explicit message in the encyclical text Laudato si' (Francis, 2015), in order to decipher the social and contemporary message of the Church and how this manifest itself in Colombia’s rural culture. Analytical categories, the most significant interpretive ideas that occurred more frequently in the text, emerged and were consolidated into the following categories:

Criticism of Anthropocentrism (CA). Example: ‘We have come to see ourselves as her lords and masters, entitled to plunder her at will’ (p. 2).

Comprehensiveness of Transformation (CT). Example: ‘Integral ecology calls for openness to categories which transcend the language of mathematics and biology and take us to the heart of what it is to be human’ (p. 11).

New Paradigm (NP). Example: ‘The throwaway culture and the proposal of a new lifestyle. These questions will not be dealt with once and for all, but reframed and enriched again and again’ (p. 16).

Axiology (A). Example: ‘Our relationship with the environment can never be isolated from our relationship with others and with God. Otherwise, it would be nothing more than romantic individualism dressed up in ecological garb, locking us into a stifling immanence’ (p. 119).

Structural Problems (SP). Example: ‘he Christian tradition has never recognized the right to private property as absolute or inviolable and has stressed the social purpose of all forms of private property’ (p. 93).

Ideological Problems (IP). Example: ‘A sense of deep communion with the rest of nature cannot be real if our hearts lack tenderness, compassion and concern for our fellow human beings’ (p. 91).

Propositional Aspects (PA). Example: ‘While the existing world order proves powerless to assume its responsibilities, local individuals and groups can make a real difference’ (p. 179).

Findings

From the categories that emerged as the most significant ideas that are found most frequently in Francis text, Figure

It can be stated that mentions of the new paradigm appear in the text more frequently and are therefore more critical; this should be taken in conjunction with the propositional aspects, as together these make up the features having the greatest presence in the text. This new paradigm understood from Francis (2015) as an individualistic and technical phenomenon that demystifies humanism, the reflection on ecological elements, theological reflections and strength in the spiritual field. It is composed for individuals who are willing to meet consumerism, which, in the terms used by Biagini & Fernandez-Peychaux (2013), enthrones the ego, and respond to individualistic dynamics of the market society.

Regarding the characterization of the social and pastoral activity carried out by the Church: 83% of its activities were focused on helping those most in need (the elderly, and patients with a greater need), purchasing medicines, holding raffles to raise money to give financial aid, and making hospital visits and visits to the homes of the disabled. The remaining 17% of its activity was aimed at developing religious festivals and local arrangements for the community infrastructure. No community projects focused on environmental care were evident. Another notable result was that 83% of those giving social and pastoral care recognized that individualism or an individualistic culture had led to a deterioration in community relations and agreed that the phenomenon coincides precisely with the arrival of the Internet in rural areas.

66% of the parishes claimed to know the text Laudato si' and its overall message, while 34% said that they did not know of it. It is clear that all of the 66% who said that they knew the text thought of it as a text which speaks to all on the environment. It was also found that in 83% of the parishes in the survey there was a perception that many take part in activities for their individual spiritual benefit and not for the benefit of the community. It was also found that in 68% of the parishes people felt that the Colombian electoral system affects community projects, because joint projects depend on whether or not the government gives support.

Conclusion

The Internet is the technological phenomenon that transmits characteristics of the market society to the composition of cultural identity in rural areas. While the logic of consumption is not sufficiently established a context with of poverty and inequality mentioned above, the internet it is the only window in which cultural exchanges are taking shape and through which social actors and pastoral practices are affected. These cultural exchanges are deepening the problem of individualism, which is part of the new paradigm described by Francis (2015) and an objective characteristic of contemporary society. Of course, it would be easy to talk about cultural exchange within the framework of a positive globalization, but to speak of exchange when the globalism mentioned by Baeza (2006) directs the situation towards homogenization, complicates the situation.

The first challenge is to develop an environmental awareness in the community, which may arise from the arguments discussed above on the social and contemporary thought of the Church, which defines the common environment (common home), the planet, and the environment as subjects for which everyone has responsibility.

The second challenge is to define how to understand the impact, in terms of content and significance, of a technology like the Internet in spaces that had been free of the globalist onslaught that characterizes the dynamics of the market society.

The rural culture and the social and pastoral identity of the Church, which exist within a context of poverty and low population density, contain elements that do not favour the full development of characteristics of the New Paradigm such as consumerism or the fetishism of subjectivity. In conclusion, rural identity and social pastoral can be classified as antagonistic niches of the market society, antagonistic niches to globalism. The identifying features of rural culture could be enhanced by the pastoral identity, and vice versa. This practice may encourage the creation of comprehensive mechanisms to meet the challenges raised here, but the common core defining pastoral practice and peasant identity, which does not come from a unity of purpose, is only a coincidence that was found in the context of this investigation

References

- Alexander, J. (1997). Las teorías sociológicas desde la segunda guerra mundial. Barcelona: Gedisa.

- Baeza, M. (2006). Globalización y homogeneización cultural. Sociedad hoy, (10), 9-24. Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/902/90201002.pdf

- Bauman, S. (2006). Liquid fear. Contemporary society and fears. Barcelona: Paidós.

- Benedict XVI (2009). Caritas in Veritate. On integral human development in charity and truth. Cart. ENC.

- Biagini, H., & Fernández Peychaux, D. (2013). ¿Neoliberalismo o neoliberalismo? Emergencia de la ética gladiatoria. Utopía y Praxis Latinoamericana, 18 (62), 13-34.

- National Administrative Department of Statistics (2014). Censo Nacional Agropecuario. Bogotá.

- Francis (2015). Laudato si', On care for our common home. Cart. ENC.

- Gadamer, H. (2000). Verdad y Método. Salamanca: Sígueme.

- Marcuse, H. (1993). One dimensional man. Barcelona: Planeta-Agostini.

- Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Cooperation (2017). Ficha país Colombia. Obtenido el 07 de julio de 2017 del sitio Web del Ministerio de Asuntos Exteriores y de Cooperación: Retrieved from: http://www.exteriores.gob.es/Documents/FichasPais/COLOMBIA_FICHA%20PAIS.pdf

- Lara, G., & Colín, G. (2007). Sociedad de consumo y cultura consumista en Zygmunt Bauman. Nueva época, 20(55), 211-216.

- Leon XIII (1891). Rerum Novarum, sobre la situación de los obreros. Cart. ENC.

- Rivas Gutierrez, E. (1988). La preocupación social de la Iglesia. Teología y vida, 29(2-3), 133-145.

- World Bank (2016). World Development Report 2016: Digital Dividends. Washington, DC: World Bank. doi:10.1596/978-1-4648-0671-1. License: Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 3.0 IGO

- Rivas Gutierrez, E. (1988). La preocupación social de la Iglesia. Teología y vida, 29(2-3), 133-145.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Torres, J. A. M. (2019). Rural Cultural Identity And Pastoral Care. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1048-1055). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.129