Abstract

This document shows initial results from research project INV-DIS-2567, funded by the Universidad Militar Nueva Granada, concerning internally displaced people in the town of Cajicá, Colombia. Forced displacement, physical violence against people and moral violence against society create a vulnerable situation. As of 2017, there are 6,412,946 victims of the armed conflict; natural consequences of this fact include dislodgement, confusion and pain, it is violence that breaks everyday life and goes against identity. The process emphasizes the answer that one person should give another when they’re in need, suffering or vulnerable. Getting involved enough to act depends on generating empathy for the pain and suffering of others, which provides the radical push to helpful action to relieve this pain and suffering. This research project starts from symbolic interactionism and participant observation, in order to reflect the voices of the displaced individuals. This means that the proposed methodology starts with these theoretical axioms and interview tools but expects the victims to transcend the status of mere data, thus appearing key aspects of human experience, such as uncertainty, unhappiness and painful experience, among others.

Keywords: Forced displacementmoral friendsmoral strangersvulnerability

Introduction

Forced displacement dislodges people and puts them in a vulnerable position; it is violence that breaks everyday life and goes against identity. The main consequences of forced displacement include confusion and pain over the loss of identity, personal meaning and foundation. According to Law 1448 of 2011 (Col), forced displacement is what happens to any person who has been forced to relocate within national territories, leaving their place of residence and habitual economic activities behind, because their life, physical wellbeing, safety or freedom are vulnerable or directly threatened. Regardless of its origins and reasons, a partially resolved armed conflict in Colombia has worsened internal violence, causing still greater pain on top of that caused by the economic and social reality. Civilians have been the main victims of this confrontation, over fifty years old. Even more seriously, against their will, they’ve been forced to choose between running away or submitting to armed agents.

Most of the many victims left by the armed conflict in Colombia have been forcefully displaced. As of early 2017, just a few months after the signing of the Havanna peace treaties, there were 6,412,946 conflict victims; 1,173 of them are registered in Cajicá. Therefore, the town’s Victim Aid Office reaches out to people in such straits, granting support according to national legislation framed in Victim policy.

A definition of “victim” is given in Law 1448 of 2011 (Col), article 3, which considers victims to be those people who have been damaged, individually or collectively, after January 1st, 1985, as a consequence of International Human Rights Law infractions or Human Rights violations that took place as a consequence of the internal conflict. When the victim is dead or missing, their spouse, permanent companion, and immediate family members are considered victims. If none of these persons are available, farther kin can be considered victims. Persons harmed due to their interference in assisting a potential victim or preventing victimization are considered victims as well. Being a victim does not depend on the identification, capture, or sentencing of the guilty party, or of the family relations that may exist between the victim and their assailant.

Decree 4800 of 2011 (Col), article 72, specifies the concepts of homecoming and resettlement. The latter is the process through which displaced persons decide to settle in a place other than the one they were forced to leave.

Since homecoming is a difficult choice, dependent upon the peace-building process, agreements and policies, many of these persons decide to settle in a new town. This research project is concerned with interaction potentials between communities, and how newcomers are welcomed in the town of Cajicá, considering the different communities now located in its territory and their diverse symbolic referents and signification. Further, their possible identification as moral strangers is a research objective (Velasquez, 2017).

Problem Statement

There is a current 1,885 displaced persons in the town of Cajicá. 506 of them are women, 413 are men, and 626 are underage; they encompass 644 families.

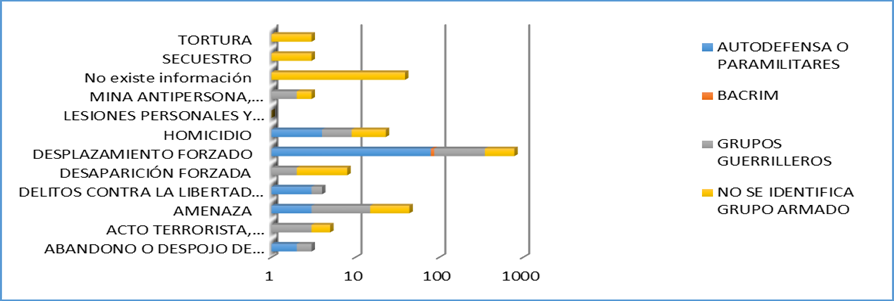

Figure

Symbolic interactionism, a theoretical and methodological perspective which fits the goals of the research techniques used in this project, provides a starting point for the procedure. Also known as cognitive sociology, symbolic interactionism lends weight to interpretation based on the social significance assigned to the world by persons who coparticipate in it (Blumer, 1982).

From this viewpoint, social reality cannot be understood as an entity predating interaction; instead, social agents’ meaning production dynamics takes precedence. Thus, the main goal is to highlight the voices of displaced persons, the true protagonists, as beings who can define a situation on their own and act accordingly. This will form the basis of an intervention proposal that will put them in mutual contact so that social interaction is generated. Social interaction as a phenomenon implies that its agents will create communicative processes, interpret, communicate and understand each other, and finally constitute groups capable of undertaking coordinated action. In keeping with the project’s framework, and the ties between conceptual and methodological elements, the possibility of interaction between diverse communities within the town of Cajicá is addressed, as is the reception of newcomers.

Research Questions

¿When can one social group’s particular problem challenge another group’s action?

Purpose of the Study

The aforementioned question emphasizes the answer that one person should give another when they’re in need, suffering or vulnerable. Getting involved enough to act depends on generating empathy for the pain and suffering of others, which provides the radical push to helpful action to relieve this pain and suffering (Levinas, 2000). But the force of the action also becomes diluted over distance, a physical or psychological separation from the other. When challenged, human beings act against or in favor of suffering, according to a socially created factor: identity. It can be said to constitute a factor in either separation or union. This agrees with Sen’s opinion (Sen, 2008)

Personal history and place of origin influence identity; this much is true and basic to understanding it. Even so, how to explain that persons who share an origin and a history, fellow countrymen, feel no empathy for others and no need to take action to relieve the suffering of others who share the same history, the same source? The answer lies in the fact that each person belongs to a group, in this case a single nation, but their identity is formed also through their belonging to subgroups determined by politics, parties, religion, class, gender, ethnicity, and so on. Current society is made up of many communities and ideologies. This allows for commitment to action, but only within the group of moral friends.

The difficulty remains in establishing solidarity and moral behaviors towards moral strangers, with whom no referents are shared. Therefore, action must be agreed upon, since the binding content is lacking, and the principle of respect must be given precedence (Engelheartd, 1995). The idea of justice relates to the idea of the society it’s embedded in (Nussbaum, 2006). Colombia is building a social reorganization in which heretofore marginalized members of society must be included, and victims of the fifty-year-long conflict must be recognized.

In light of all this, this research intends to lay the foundations for an explanation, a working hypothesis that will allow further inferences. A possible formulation for such a hypothesis goes: if the people of one nation participated and acted according to identity-building situations, a morally committed nation would follow.

Research Methods

The methods and procedures used in this research are derived from symbolic interactionism and participant observation. This means that the proposed methodology starts with these theoretical axioms and the interview tool but expects the victims to transcend mere data and key aspects of human experience, such as uncertainty, unhappiness and painful experience, to be included. With this in mind the methodology is complemented by technically conducted participant observation, which allows researchers to immerse themselves in the sociocultural context and keep a field diary. According to Guber (2001), this presence, direct experience and perception of the target populations everyday life, guarantees the trustworthiness of gathered data and the sensorial learning that underlie such activities.

Field diaries were used as raw materials, information to establish the interview questions and later analyze the situations detected in the interviews. They also helped create categories that fed into NVivo software-conducted triangulation and analysis. This related the work with the thinking of Rodríguez, Gil, & García (1999), who believe interviews hide what is important and meaningful unless the researcher becomes immersed in the context. Taken together, these tools (field diary and interviews) helped determine the continued existence of situations and perceptions in the context the researcher came into, helped ask after and find the meaningful aspects, and put them out in such a way that the interviewee’s classification and relation with their own life are evident.

Findings

One important finding from the interviews is that Cajicá-born people are unaware of the presence of forcefully displaced persons within their territory. This is due to the fact that victims conceal their situation in job searches and personal identification: they might fear to be identified as members of a guerrilla group. One reason displaced persons settle in Cajicá is the creation of affective relationships with native inhabitants. Thus, a generation of Cajicá-born is developing in the context of a link between the native inhabitant and the foreign victim. This is how the displaced person begins to project and organize a new life in the municipality. Settling is also related to the ease with which new arrivals can find economic stability. These aspects must be contrasted, weighed and fitted with other aspects of the research in order to test the hypothesis that guides this research.

Conclusion

The following conclusions are only partial, inasmuch as the research is still ongoing. Confirming the hypothesis and related to the findings mentioned, solidarity can be found to stop at moral friends with whom identity is reached. Displaced persons hide their circumstances during social interaction because it might relate them to the symbol of guerrilla fighters. Groups that resulted from violence in the conflict are still undifferentiated, which categorizes them all as moral strangers.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Universidad Militar Nueva Granada - Vicerrectoría de investigaciones (research vice-principal’s office) for funding research project INV-DIS-2567, entitled: "La población en situación de desplazamiento forzado, una mirada desde el enfoque diferencial" (Forcefully displaced persons, viewed from a differential approach), through internal call “vivencia 2018”.

References

- Blumer, H. (1982). Interaccionismo simbólico: perspectivas y método. Barcelona: Hora SA Editora.

- Engelheartd, T. (1995). Los fundamentos de la bioética. Madrid: Editorial Paidós.

- Guber, R. (2001). La etnografía. Método, campo y reflexividad. Bogotá: Grupo Editorial Norma.

- Ley 1448 de 2011. (Col.) Por la cual se dictan medidas de atención, asistencia y reparación integral a las víctimas del conflicto armado interno y se dictan otras disposiciones.

- Ley 1190 del 2008. (Col.) Por medio de la cual el Congreso de la República de Colombia declara el 2008 como el año de la promoción de los derechos de las personas desplazadas por la violencia y se dictan otras disposiciones.

- Levinas, E. (2000). Ética e infinito. Madrid: La balsa de la medusa.

- Nussbaum, M. (2006). Las fronteras de la Justicia. Barcelona: Paidos.

- Rodríguez, G., Gil, J., & Garcia, E. (1999). Metodología de la investigación cualitativa. Málaga, España: Aljibe.

- Sen, A. (2007). Identidad y violencia. La ilusión del destino. Buenos Aires: Katz Editores.

- Velasquez, L. (2017) Problemática moral – justicia y derechos humanos – responsabilidad social: desplazamiento una mirada al municipio de Cajicá Colombia. In Llalla, W. VI Congreso de Psicología y Educación. Lima. Retrieved from: https://www.picorpcolombia.com/editorial-1/registrados-memorias/

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Fandiño, L. V. (2019). Vulnerability And Forcefully Displaced Persons In Colombia ¿Moral Friends Or Moral Strangers?. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 1026-1030). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.126