Abstract

The Incheon Declaration, approved by UNESCO in 2015, plays a key role in the international context, by collecting recommendations and progress in the inclusive and intercultural education. The organizations that contribute in the educational field, are participating by accomplishing the Incheon Declaration goals. By taking the normative references as starting point, the role of NGOs, foundations, associations and religious organizations contribute to the socio-educational needs of every person. The aim of this research is to go deep into the training needs of professionals working in social organizations, due to their key role in the intercultural competency recognition as the main strategy to empower people and groups coming from increasingly diverse contexts. This research is a descriptive study and an analysis of the intercultural competency needs, skills and abilities in the third sector and its professionals. The methodology is based in a customized survey, filled by 80 professionals from the third sector. The results are a fundamental contribution to the diagnose of professionals’ educational needs, who work in diverse contexts and demand intercultural training.

Keywords: Inclusive educationinterculturalityprofessionalssocial organizationsthird sectortraining needs

Introduction

NGOs, foundations, associations and religious organizations address people needs, from the most basic ones (related to physiology and safety) to those that threaten the basic human rights, and those that guarantee people and groups’ sustainability, by providing recognition and self-fulfilment, as well as personal and professional development.

As part of these organizations, their professionals play a key role: volunteers, technical and management staff, and directors who require an update of their competencies and intercultural training. These professionals require reinforced profiles to properly address the needs of the programs’ beneficiaries. As Pérez (2008) states, the evolution and development of these profiles is clear “

The Incheon Declaration for 2030 Education (Declaración de Incheon y Marco de Acción para la realización del Objetivo de Desarrollo Sostenible 4, 2015) has been decisive for the fourth Sustainable Development Goal (SDG 4). It is related to education, and pursues an inclusive, fair and high-quality education, by promoting lifelong learning opportunities for everyone. This Declaration is inspired by the humanist conception of development and education, based in human rights and dignity, social justice, inclusiveness, protection, and cultural, linguistic and ethnic diversity.

The Global Education Monitoring Report (GEM Report) 2017, provides a valuable perspective for governments and policy staff, to track and accelerate the SDG 4, by following its indicators and goals, and measuring the general success of equity and inclusiveness initiatives. This Report defines the fundamental change of education, wellbeing and international development, as one of its key messages. Education takes the responsibility of promoting the right competencies, attitudes and behaviours to drive a sustainable and inclusive development.

A definition of the third sector organizations is provided by the Law 43/2015, second article, of the Third Sector, Social Action:

(1) The Third Sector of Social Action entities are private organizations of different profiles, from social or citizen initiatives, that apply the solidarity and social participation criteria, general interest and non-profit, and enhance the recognition of civil rights, as well as the social, cultural and economic rights of vulnerable people and groups, sometimes under social exclusion risk.

In 2015, the Social Action NGO Platform, as part of the Active Citizenship Program, published the Report about the Social Action Third Sector (TSAS), that analyses the social action entities in Spain. It describes the situation of a sector that works connected, closed to the most vulnerable people in our country, with more than 53 million of direct attention actions. The aim of this research was to describe the situation and challenges of Social Action Third Sector entities (TSAS), as information provided in 2015. This report states that these entities’ staff represent 4,6% of the total employed people (EPA). This is a high qualified employment, most women and young people. These numbers represent a high professionalization level, with specific professional competencies for the third social sector.

Moreover, the multicultural reality demands the competencies of organizations and groups. As Bartolomé (2001) states, “empowerment education requires a thoughtful consideration of the strengths, experiences, strategies and goals of the most vulnerable groups. It also requires helping these groups to analyse and understand the social structure and the skills development, in order to successfully accomplish their goals” (p. 35). The intercultural education is developed through this process. This training, as Paige and Martin (1996) define, “is a transforming education for people, groups and organizations” (p. 45).

In the study conducted by Fullana, Pallisera, and Planas (2011), relevant findings about training needs for socio-educational professionals were attained. “Among the training needs perceived by professionals, the most relevant are those related to interpersonal communication (intervention, familiar conflict resolution, interculturality, work with groups, etc.), project evaluation, and design and management of plans, programs and projects for groups and individual needs” (p. 3). These conclusions reinforce the ideas stated in this article.

For the third sector professional, this change means a higher range of opportunities, influenced by a new professional demand. In the intercultural education context, the professional training is defined along with organizations. That means adapting organizations work to its cultural racial and ethnic richness, enhancing attitudes and values of respect through explicit actions, and restructuring the culture work to reflect its diversity. As quoted by Grant and Sleeter (2007) “

Problem Statement

The community and social field, known as third sector, is playing a key role, not only in the development of actions that cover vulnerable groups’ needs, but in the decision-making process at international forum levels, to design strategic policies that address needs from their roots. From this point, part of our research, identify the needs of these professionals to develop intercultural competence and meet the demands of an increasingly diverse population.

Research Questions

Among the research questions that we pose: Is a specific training in intercultural matters necessary to offer more specific attention to a more diverse society? What are the specific competences linked to intercultural education on which the professional of the third sector would need to improve their training? What is the level of specialization of third-sector professionals in intercultural competence? Is it important that the figure of the intercultural mediator exists in the organizations linked to the third sector?

Purpose of the Study

The goal of this study is to go deep into training needs of professionals who work in social organizations and entities, due to its increasing relevance in the intercultural competency recognition as main strategy to empower people and groups, in increasingly diverse environments and societies.

The specific goals are to design a sociodemographic profile of third sector professionals who work in intercultural education, and understand the subjects related to the intercultural competency, their level of understanding, and the training needs of survey’s participants.

Research Methods

To describe the reality of the intercultural competency of third sector professionals, a quantitative, non-experimental methodology has been applied. Specifically, it is the survey analysis. A definite questionnaire was designed to collect the information. Most of its items were closed questions, defined as a grade qualification and Likert type. The brief questions help participants to detail some of their answers.

Participants

The research is referred to the third sector professionals. To define the sample, professional networks as LinkedIn were used, to identify the sector professionals and select those with relevant experience in this field. We also reached out to specialized entities, that sent the invitation to their professionals (platforms of social organizations related to intercultural education).

Tools and procedure

As tool to collect the data, the most employed technic in survey research was applied. A specific questionnaire for this study was defined, after a bibliographic revision of the subject (Aneas, 2003; Cernadas, Santos, & Lorenzo, 2013).

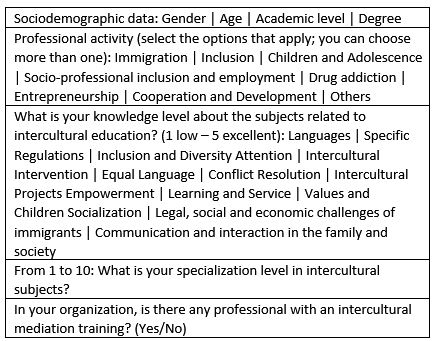

The aim of the survey “Intercultural competency needs of the third sector professionals” is to go deep into training needs of social organizations’ professionals. The statements are specific enough to ensure that every item accomplishes its goal, so the researcher highlights the required information. Following Babbie’s orientation (1998) to design effective statements and questions, items are drafted in a clear and straightforward way, so these are specifically referred to the subject of the study. Subjective and negative items have not been used (Figure

Once information about the research goal was provided, surveys were sent through a message to 150 participants, including a Google Forms link. 80 social professionals of the third sector completed the survey. As the Research Group REBIUN states in their Science Report 2.0: social web application in research (REBIUN, 2010), the social web provides services that can be used as research instrument, since they provide services required for planning, documentation, experimentation and sociological research different processes can be done through the web. Additionally, these can be shared with other researchers, that is the participative element 2.0 Google Forms allow surveys’ submissions that can be shared.

The intern consistency method, Cronbach´s Alpha, was used to evaluate the reliability level. Once this coefficient was applied to our scale results, 0.90 was obtained. The survey’s validity was made by judges. A group of 10 education research experts evaluated the survey, to find possible understanding and analysis mistakes, and measure the submission time. The group applied changes and improvements to some of the items.

Prior to the factorial analysis of the main components, information about two measures related to the analysis application compliance was obtained:

The measure of the sample fit of Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) provided information about the sample adaptation. 0,884 was obtained as KMO value. This means that the factorial analysis is practical and useful for this study.

The Barlett sphericity test analyses the equal hypothesis of correlations matrix with the identity. In our analysis, the significance is adequate, as the value is less than 0,00005. The null hypothesis can be refused, considering the values adjustment by the ideal factorial analysis.

After analysing the main components, 3 factors were obtained. These components (self-values ≤ 1) explains 68,44% of the total variance.

For these factors´ extraction, the method of the Main Components’ Analysis was applied, through a rotation of Varimax normalization with Kaiser, that converged in 4 iterations. The factors’ regrouping is shown in table

The first factor is the one with the highest number of items. It is defined as “Complementary knowledge to the intercultural competency”. This factor includes a group of items that participants consider relevant and complementary to interculturality as competency. The third sector professional who master the intercultural competency should know about inclusion and attention to diversity, manage intervention tools, know the equal language, master in conflict positive management, be able to empower through intercultural projects, as well as know about learning and service, values and children socialization; legal, social and economic problems of immigrants, and communication and interaction in the family and society. Items 14.1 and 14.2 saturate factor 2 “Key knowledge in the intercultural competency”. Participants define languages and specific regulations as key elements of the intercultural competency. Lastly, the “Professional specialization in the intercultural competency” is under factor 3, with a significative factorial value, which means that it is a key factor for participants.

Findings

The results represent a fundamental contribution in terms of the needs’ diagnosis of educational professionals, working in diverse environments and demanding intercultural training.

Sociodemographic data

In our research, we notice that professionals working in the third sector represent a high qualified profile, with 66,3% of women and 33,8% of men. Most of the participants age range between 25 and 44 years (73,8%). In terms of academic level, most of the participants possess a degree level (92,6%), in subjects related to Social and Legal Sciences (Pedagogy, Social Education, Psychology, Social Work) and develop their professional activity in Associations (31,3%), Foundations (26,3%), NGOs (15%) and Corporate Social Responsibility (6,3%). As stated by the Social Action of Third Sector Report (2015), these results represent a high level of professionalization in specific competencies, to put into practice in the social third sector.

In terms of the activity field, professionals work in the following areas, sometimes participating in more than one, and being the most significative mentioned: children and adolescence (41,3%), immigration (30%), inclusion (26,3%), professional integration and employment (32,5%), and cooperation and development (13,8%).

Lastly, as data referred to the sociodemographic profile of participants, 55% has more than 5 years of experience in the social field. 20% of participants have 1, 2 or 3; 16,3% has 3, 4 or 5 years, and 8,8% of participants have less than one year of experience in this field.

Regarding the professional profile, 63,7% work with immigrants frequently; and as starting point for the rest of the analysis, only 38’8% of participants consider that their intercultural training is adequate.

Influence of some variables in the intercultural competency training of the third sector professionals

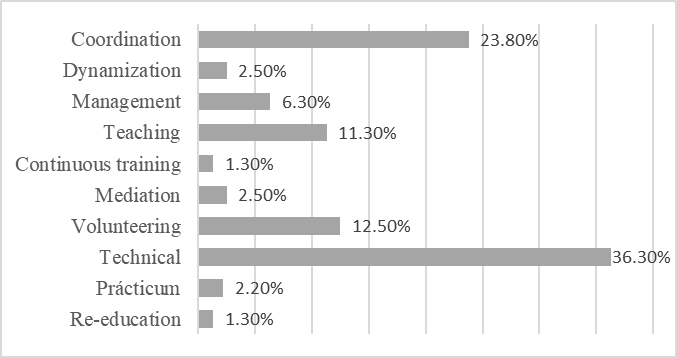

Once the descriptive analysis is done, and considering the statistical significance technics, we analyse the influence of some personal and professional characteristics of participants, considering ten variables: gender, age, academic level, type of organization, area, role in the organization, years of professional experience, interaction with immigrants, participation in training initiatives about intercultural education, and the role of the intercultural mediator.

Significant differences were observed in the gender variable for some items. Women reflected a lower sense of preparation in intercultural education. Moreover, they showed a higher need of the presence of intercultural mediators. Regarding the age, there are no significant differences, based on the ranges established in the analysis. Previous experience with immigrants didn´t have a major influence in participants’ opinions about this matter. Differences came from a lower sense of preparation of participants working directly with immigrants.

Participants who have participated in training initiatives about intercultural education have a higher sense of their implication in this field. Additionally, they find the presence of intercultural mediators highly needed, and find the training in intercultural education very convenient for the third sector professionals.

Conclusion

Training in intercultural education of third sector professionals means a change in the traditional perspective of professional development. This training is continuous and forsees demographic, social and cultural changes to work in a preventive way and facilitate most vulnerable groups’ integration. It also implies the development of socioemotional abilities to offer experiences of significative learning; and innovative initiatives that provide adapted learning to groups and professional needs, by using pilot and test models (Uvin, Jain, & Brown, 2000; Kymlicka, 2003).

Among the principal conclusions from the analysis of intercultural education training of third sector professionals, we can highlight the following:

The importance of including intercultural education training as part of these professionals’ training is generally accepted.

Opinions depend significantly on participants’ age and professional experience.

Third sector professionals show preferences determined by the training subject, specially languages (English, 92,2%, and French, 37,5%, are the most studied languages among participants) and specific regulations about interculturality. These are key dimensions, as different International Human Rights Declarations and the Incheon Declaration (2015) in its fourth objective about education have stated.

Inclusiveness and attention to diversity, management of intervention tools, knowledge about equal language, positive resolution of conflicts, ability to empower through intercultural projects, knowledge about learning and service, and values and socialization of children, play a key role as complementary subjects of this profile. The social, legal and economic problems of immigrants represent a special interest and need for the intercultural training of third sector professionals (63,8%).

This research confirms the results of Fullana, Planas, Soler, & Tesouro (2011) about training needs defined by the socio-educational professionals. These needs are related to intervention, conflict resolution in families, interculturality, work with groups, etc.

Consequently, guarantee the values and attitudes through multiculturality is relevant in the third sector professional, and key to enhance a real intercultural dialogue between organizations and groups. We conclude that the results of our research are aligned to the educational perspectives defined by the OECD in 2017. Skills such as tolerance, collaborative problem resolution, and communication in different contexts are highly valued.

References

- Aneas, A. (2003). Competencias interculturales transversales: un modelo para la detección de necesidades de formación. Universidad de Barcelona. (Tesis doctoral). Retrieved from: http://www.tdcat.cesca.es/TESIS_UB/AVAILABLE/TDX-1223104-122502//0.PREVIO.pdf

- Bartolomé, M. (2000). La construcción de una ciudadanía crítica. ¿Tarea educativa? In Pinilla, R. Feito, L. (Eds.) Atreverse a pensar en la política (pp. 45-56). Madrid, España: Universidad Pontificia Comillas.

- Cernadas, F. X., Santos, M. A., & Lorenzo, M. del M. (2013). Los profesores ante la educación intercultural: el desafío de la formación sobre el terreno. Revista de Investigación Educativa, 31 (2), 555-570. DOI:

- Declaración de Incheon y Marco de Acción para la realización del Objetivo de Desarrollo Sostenible 4 (2015). Hacia una educación inclusiva, equitativa y de calidad y un aprendizaje a lo largo de la vida para todos. UNESCO.

- Fullana, J., Pallisera, M., & Planas, A. (2011). Las competencias profesionales de los educadores sociales como punto de partida para el diseño curricular de la formación universitaria. Un estudio mediante el método Delphi. Revista Iberoamericana de Educación, 56(1), 1-13.

- Fullana, J., Planas, A., Soler, P., & Tesouro, M. (2011). La formación continua de los profesionales de la acción socioeducativa. Un estudio de necesidades. Bordón, 4, 29-42.

- Grant, C. A., & Sleeter, C. E. (2007). Doing multicultural education for achievement and equity. New York: Routledge.

- Leiva, A. (2012). La formación en educación intercultural del profesorado y la comunidad educativa. Revista Electrónica de Investigación y Docencia (REIDe), 2 (12), 8-31.

- Informe de seguimiento de la educación en el mundo (2017). Reducir la pobreza en el mundo gracias a la enseñanza primaria y secundaria universal. UNESCO.

- Informe Ciencia 2.0: aplicación de la web social a la investigación (2010). Red de Bibliotecas Universitarias Españolas (REBIUN). Retrieved from: http://eprints.rclis.org/3867/1/Ciencia20_rebiun.pdf

- Kymlicka, W. (2003). Multicultural states and intercultural citizens. Theory and Research in Education, 1(2), 147-169. Doi:

- Paige, M. R., & Martin, J. N. (1996). Ethics in Intercultural Training. In Paige, M. R; Martin, J. N (Eds.) Handbook of Intercultural Training (pp. 35-59). California, United States: Sage.

- Panorama de la Educación. Indicadores de la OCDE (2017). Madrid, España: Fundación Santillana. Retrieved from: http://www.fundacionsantillana.com/PDFs/PANORAMA%20EDUCACION%202017.pdf

- Pérez, J.C. (2008). El técnico superior en integración social. Apuntes sobre su perfil y formación. Cuadernos de Trabajo Social, 119(21), 119-140.

- Uvin, P., Jain, P.S., & Brown, L.D (2000). Think large and act small: toward a new paradigm for NGO scaling up. World Development, 28, 1409-1419. DOI: 10.1016/S0305-750X (00)00037-1.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

09 April 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-059-4

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

60

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1062

Subjects

Multicultural education, education, personal health, public health, social discrimination,social inequality

Cite this article as:

Aguilera, F. J. G., Lizaola, C. F., & Moreno, E. V. (2019). Intercultural Competency Needs For The Third Sector Professionals. In E. Soriano, C. Sleeter, M. Antonia Casanova, R. M. Zapata, & V. C. Cala (Eds.), The Value of Education and Health for a Global, Transcultural World, vol 60. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 81-89). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.04.02.11