Abstract

Based on a simple mathematical model, the coefficient of susceptibility to extremist ideology of the youth of the Republic of Dagestan at the beginning of the 21st century is estimated. The explanation of high values of this coefficient in 2006–2011 is proposed. The level of tension in Dagestan, measured by the change in normalized indicators, is shown: the number of murders and attempted murders, the number of suicides and the difference in divorce rates and marriages began to grow later than terrorist activity and was not the cause, but the consequence of increased terror. The analysis of statistical data shows that the attractiveness of extremism in Dagestan during this period cannot be associated with the deterioration in the standard of living. The possible impact of ousting of terrorist groups from Chechnya on terrorist activities in Dagestan is being analyzed. According to available data, such effect took place, though was insignificant. It is hypothesized that the main reason for the increase in extremist activity in the period under review was the maturing of the generation whose religion was the basis of the world outlook. Radical trends in Islam, which effectively used social exclusion, political inactivity and theoretical weakness of official Islam in the face of growing social and economic inequality, had a significant impact on formation of youth in this period. A certain role was played by accelerated urbanization and tough force, carried out not only in relation to ultra-radicals connected to terrorist groups, but also to moderate radicals.

Keywords: Terrorismmodelyouthreligiousideologyinequality

Introduction

Terrorist actions have been described in historical sources since ancient times (Metelev, 2008, p.5), (Ola, 2015). Nowadays, starting from the 1960s, a significant surge in terrorist activity has been observed (Ola, 2015). At the same time, there is still no universally accepted definition of the term “terrorism”. Different scientists and societies understand it in various ways (Daskon, 2016).

Thus, for example, in the Federal Law of the Russian Federation No. 35-FL dated March 6, 2006 (as amended on April 18, 2018) “On Countering Terrorism”, terrorism is defined as “the ideology of violence and the practice of influencing state authorities, local governments or international organizations in the field of decision-making, related to the intimidation of the population and (or) other forms of unlawful violent acts”; terrorist activities are defined as “activities, including: a) the organization, planning, preparation, financing and implementation of a terrorist act; b) incitement to a terrorist act; c) the organization of an illegal armed group, a criminal community (criminal organization), an organized group for the realization of a terrorist act, as well as participation in such a structure; d) recruitment, arming, training and use of terrorists; e) informational or other aiding in the planning, preparation or implementation of a terrorist act; (e) propaganda of terrorist ideas, dissemination of materials or information calling for terrorist activities or proving or justifying the need for such activities.”

In the article (Daskon, 2016), terrorism is understood as a politically, ideologically and religiously or culturally induced threat or violence, designed to achieve certain goals through extreme destruction and intimidation. The article (Beck, 2008) states that terrorism: (1) includes violence or the threat of violence; (2) is aimed at non-traditional purposes (for example, at violence against civilians); and (3) is related to political objectives or the formation of political claims. It should be pointed out that violence with the purpose of intimidation is used not only by radical opposition groups, but also by governments in order to suppress the opposition (Ola, 2015).

Scientists are still far from understanding what conditions lead to terrorist actions (Ehrlich & Liu, 2002). In our opinion, this is due to the lack of a common understanding of the nature of terrorism. “There are three main views on the nature of terrorism based on the combat, criminal and socio-political manifestations of terrorist activity. In accordance with the first position, terrorism is considered to be a specific type of armed action and is defined as a “low intensity armed conflict”. The second point of view focuses on the criminal component and classifies terrorism as a type of common crime. The third one considers terrorism to be a type of political struggle emerging on the basis of social and political protest. ” (Metelev, 2008, p.10)

It is obvious that terrorism is associated with armed actions of guerrilla and rebel groups, violent crimes (primarily murders and armed robberies that are committed to finance terrorist organizations) and a protest against the conditions of existence, but does not amount to them. However, the presence of such a connection makes it difficult to identify the causes of the rise and fall of terrorist activity. As a result, there is a lack of a theoretical basis for analyzing terrorist activity, which leads to a limited understanding of the reasons for changes in terrorism (Bakker, 2012).

For example, in the academic literature there are opposing views on the role of poverty in the spread of terrorism. On the one hand, there is a significant link between poverty, inequality and the spread of terrorism (Ehrlich & Liu, 2002; Ola, 2015; Antonyan, 2004), which is often used in presentations made by political and public figures. On the other hand, the work (Daskon, 2016) states that there is no significant link between terrorism and poverty, but it is noted that poverty provides support for terrorists from groups that feel disadvantaged. Often, poverty is used to justify terrorism (Daskon, 2016). The work (Lee, 2011) notes that the involvement of the poor in terrorist groups is hampered by their poor awareness and lack of spare time. It also indicates the lack of correlation between terrorist acts in various countries and the level of per capita GDP in them.

Analysis of effects of poverty on terrorism is aggrevated by the fact that, as stated in the work (Krueger & Malečkova, 2003), with the same state of the economy, countries with a high level of civil liberties are less prone to the emergence of terrorist groups. It has been argued that terror is a response to political conditions and a long-lasting sense of humiliation and frustration, which has little to do with economics (Krueger & Malečkova, 2003). Therefore, it is sometimes believed that terrorism occurs under the influence of “social poverty”, which implies a limited choice of opportunities, little freedom, insecurity and powerlessness (Daskon, 2016).

Often, the influence of the low level of education on terrorist activity is mentioned in statements of politicians. At the same time, A. V. Krueger and J. Malečkova (Krueger & Malečkova, 2003) point out that terrorist organizations prefer to involve well-educated people in their activities. It is known that most of the members of Al-Qaida have a university education (Daskon, 2016), and the leaders of terrorist groups are more educated than their followers (Ola, 2015). Those having a definite opinion on political processes are more often involved in terrorist groups. As a rule, this population group is richer and better educated than the rest of the population. At the same time, those who have the lowest status among the educated and politicized part of society are involved in terrorist groups. Poor education can be dangerous – people with incomplete education involved in political activities are often the most dangerous for society. Students and unemployed people with education are frequent among terrorists. In general, any connection between poverty, education, and terrorism is indirect, complex, and probably quite weak (Krueger & Malečkova, 2003).

The widespread opinion about the influence of the religious factor on terrorism is also not supported by research (Krueger & Malečkova, 2003). Although the discrepancy between the requirements of idealized religious doctrine and the real life of society is considered as one of the causes of terrorism (Beck, 2008).

The impact of cultural and individual factors on terrorist activity has been hardly studied due to the extreme complexity of their measurement and interpretation (Ehrlich & Liu, 2002), but at the same time, it is noted that the factors influencing terrorist activity are different in different countries and for different social groups (Ola, 2015). For terrorists with ideological or religious motivation, cultural characteristics can be particularly significant (Beck, 2008).

Ola T.P. (Ola, 2015) believes that terrorists are people who feel unhappy for some reason, and these reasons can be quite various. Participation in terrorist activities is also influenced by the desire to be included in an active group pursuing certain goals or a sense of injustice (Ola, 2015). The impact of tensions related to the modernization of society and foreign military occupation is also indicated (Beck, 2008). The work (Lee, 2011) notes that the urban, more “modernized” part of the population also turns out to be more violent.

On the one hand, repressions on the part of the authorities prevent the establishment of terrorist groups, but on the other hand they lead to the radicalization of regime opponents and the emergence of myths and images of martyrs that militants use to justify their actions (Beck, 2008). Empirical analysis shows that blind repression leads to increased terrorist activity (Zahedzadeh, 2017).

Note that the problem of involving new members in terrorist groups, despite its importance, is poorly developed in the scientific literature (Shegaev, 2017). It is believed that the creation of significant terrorist groups requires three components: the inefficiency of state administration, the presence of mobilizing extremist views and people who can spread these views (Zahedzadeh, 2017).

It should also be noted that terrorism is not a static, but a noticeably changing phenomenon over time, and local causes cannot explain the emergence of global bursts of terrorism (Bakker, 2012; Zahedzadeh, 2017). Analysis of changes in terrorist activity over long periods of time shows that transnational terrorism changes periodically with peaks occurring every two years (Zahedzadeh, 2017).

Taking into account the above, the most promising approach in studying the causes of terrorist activity is the study of specific bursts of terrorism and the synthesis of the results obtained taking into account economic, social, demographic, cultural and historical features of the areas under consideration.

Problem Statement

The level of terrorism in the post-Soviet space is not considered to be critical. The only exception is the North Caucasus, which can be attributed to extremely dangerous territories in accordance with the international security index (Vnukova et al., 2014). Terrorist activity in the North Caucasus at the beginning of the XXI century underwent several stages. In the first stage (2001–2006) the bulk of militants concentrated in Chechnya and, accordingly, the overwhelming number of terrorist acts took place there. Then, there was a relatively brief surge in violence in Ingushetia (2008–2009), see (Sushchy, 2013; O’Loughlin, Holland, & Witmer, 2011).

Since 2010, the Republic of Dagestan has become the center of terrorist activity in the North Caucasus. In 2011–2012 it accounted for more than half of all terrorist acts in the region (Sushchy, 2013). The rise in terrorist violence in Dagestan began in 2002 (O’Loughlin at al., 2011). In 2005, the peak of terrorist activity was observed (Dobaev, 2009), and then, after a certain decline, the activity of the militants increases dramatically again. The noticeable improvement of the situation began only in 2014.

The task of finding out the reasons for the growth of terrorist activity in the Republic of Dagestan from 2010 to 2014 applying a simple mathematical model is set.

Research Questions

The subject matter is to identify the features incident to terrorism in the North Caucasus. As well as to study the spatial and temporal dynamics of terrorist activities in this region. In particular, to assess the influence of ethno-confessional, economic, political factors, including the clash of interests of various countries and trans-national groups.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the work is to analyze the possible causes of a surge of terrorist activity in the Republic of Dagestan in the early 21st century and identify the most significant ones among them. According to the review of literary sources, the causes of terrorism can be: poverty, inequality in income distribution, unemployment, education, urbanization, the impact of extremist ideology and repression by the state. And one purpose is to demonstrate the possibility and effectiveness of the mathematical modeling use in the study of terrorist activity.

Research Methods

The analysis of terrorist activity is based on the statistical data on the number and types of terrorist acts, the number of victims, and the losses of militants. It is difficult to estimate the number of terrorist acts with sufficient accuracy, both because of the irregularity and, often, contradiction of the data provided in open sources, and the inability to separate criminal offenses and terrorist acts completely.

In the Republic of Dagestan, a rather detailed chronicle of terror can be found on the website of the Caucasian Knot (Dagestan: Chronicle of Terror (1996–2018), 2018). The estimate of the number of committed and prevented terrorist acts and armed clashes in Dagestan, made by us according to this site, is given in Table

Table

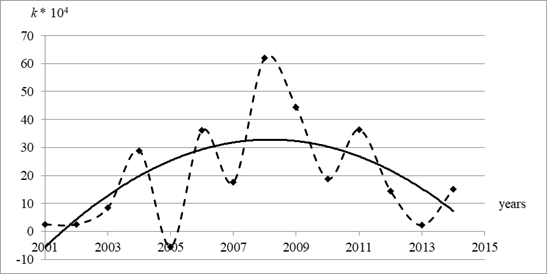

The increase in the number of terrorist acts, observed since 2007, was most likely due to the increase in the number of terrorists. It is extremely difficult to assess the change in the number of active members of the underground gangs and those, who participated in the implementation of terrorist acts occasionally. To estimate the number of terrorists, we use the data given in the book (Sushchy, 2013, p. 324), which shows that the number of terrorists can, as a first approximation, be considered proportional to the number of terrorist attacks. We will use the upper estimate, i.e. consider the number of terrorists equal to the double number of terrorist acts.

To analyze the dynamics of change in the number of terrorists, we use a simple mathematical model:

(1)

(2)

where is the total number of men aged from 18 to 26, is the change in the number of men between the ages of 18 and 26 dissatisfied with the state of society over a period of time , is the tensions in the society, is the number of members of terrorist groups, is the change of this number over a period of time , is the rate of involvement of disgruntled young people in terrorist groups by using the information channels, is the rate of involvement of people in terrorist groups due to contacts with participants of these groups, is the rate of neutralization of terrorist groups members by law enforcement officers. Note that the first equation of the system is equivalent to the expression , i.e. the number of dissatisfied members of a social group (in this case, young men) is proportional to the group size and its tension. A similar model was used to analyze terrorist activity in Kabardino-Balkaria (Basaeva, Kamenetsky, & Hosaeva, 2017).

Note that the first equation of the system is equivalent to the expression , i.e. the number of dissatisfied members of a social group (in this case, young men) is proportional to the size of the group and its tension. A similar model was used to analyze terrorist activity in Kabardino-Balkaria (Basaeva, Kamenetsky, & Hosaeva, 2017).

The age range in which young people get involved in terrorist activities is consistent with the most “dangerous” age from the point of view of the extremist ideology (Sushchy, 2013, p.384). It is possible to estimate the change in number of men of a certain age group using birth records. From 1970 to 2000 at ten-year intervals, data on the birth rate per thousand of population and number of people of the Republic of Dagestan are given in the works (Sushchy, 2009, p. 35) and (Sushchy, 2013, p. 20) respectively. Intermediate values of the number of births were determined using linear interpolation. A more accurate estimate is meaningless because of the proximity of the calculations made, which did not take into account infant mortality and migration outflow of young people. Estimation of the number of young people of “dangerous” age in the Republic of Dagestan for the period under review is given in Table

We assume that the number of young men amounts to half of the number of young people.

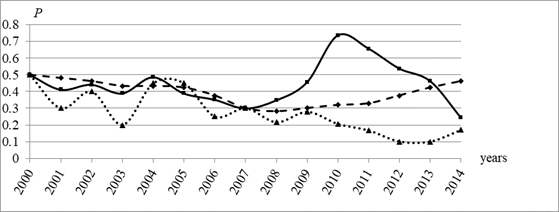

We estimate the change in the level of tension in Dagestan using standardized indicators (Basaeva, Kamenetsk & Hosaeva, 2015), in which we use the number of suicides, murders and attempted murders per 100,000 population, as well as the difference in divorce rates and marriages. For normalization, the following expression was used:

where

is the estimate of the intensity in the

It is apparent that, the indicators have behaved differently since 2009. The increase in the number of murders and attempted murders starting from this year can be explained both by the proliferation of weapons in the republic and by the difficulty of accounting murders and especially attempted murders against the background of a great number of terrorist acts. The growth of the difference in marriage rates and divorce rates is most likely due to the instability of the situation in the republic. In the calculations, we use the average values of the normalized indicators for each year to estimate the intensity (Table

Findings

Using models (1) - (2), we estimate the change in the coefficient

, which reflects the degree of susceptibility of extremist ideology by young people who are dissatisfied with the state of society. The results of such an assessment are shown in Fig.

A significant variation in the results is due to the incompleteness and inaccuracy of the source data. The results do not show a connection between the coefficient and the number of terrorists , which indicates the insignificant influence of direct contacts with terrorists on susceptibility to extremist ideology. We note the high values of the coefficient , characteristic of the period 2006– 2011, and will try to find out what caused this.

As stated in the introduction, researchers point out rising unemployment, declining incomes, and rising inequality and social injustice as the main reasons for involvement in terrorist activities. However, according to the data of the State Statistics Committee of the Russian Federation (Federal service of statistics, 2017), the republic’s economy in the period from 1995–2013 was steadily growing, and the growth rate was greater than in other republics of the North Caucasus. Also we note that terrorist activity cannot be explained by a change in the registered level of unemployment. The gap in the standard of living between the richer and poorer parts of the population widened during this period, which is reflected by the growth of the Gini coefficient until 2012. A change in social inequality is not always accompanied by an increase in discontent.

From the early 2000s until 2008, tensions in Dagestan, assessed by statistical indicators (Table

In the period from 1990 to 2000 about 130–150 mosques were annually built in the Republic of Dagestan (Sushchy, 2013, p.219). According to Dobaev (Dobaev & Dobaev, 2017), from 1990 to 1994 the creation of Dagestan Salafi groups and Islamist circles, the importation of Islamist literature and its distribution in the country are recorded. At the same time, similar literature is published on a large scale locally (for example, the Santlada publishing house in the village of Pervomaiskoye, Khasavyurtovsky region of Dagestan). The Russian Muslim youth goes abroad to get Islamic education. According to S. Sh. Muslimov (Muslimov, 2011), the propaganda of extremism turned out to be particularly effective due to the fact that adherents of traditional Islam, Sufi brotherhood, serve to the unfair, criminal power, cooperate with it and receive financial support from it. “The social alienation, political passivity of “official Islam” with its theoretical weakness, and the shortage of experts on Islam and Muslim traditions, actually increased the chances of Islamists in the ideological fight for the Muslim population, primarily for the youth” (Dobaev & Dobaev, 2017).

“We note that the authorities, unable or unwilling to distinguish between moderates and ultra-radicals, are carrying out equally harsh force measures against them. This approach reduces the already narrow layer of moderate radicals, who are gradually moving to extremist positions” (Dobaev & Dobaev, 2017). In the work (O’Loughlin at al., 2011), police brutality in the suppression of Islamic organizations of the Wahhabi direction is called as the reason for the first noticeable outburst of violence in Dagestan in 2005.

An alternative reason for the terrorist activity growth is the diffusion of the conflict from the territory of Chechnya in 2007–2011 (O’Loughlinatal et al., 2011). The definite influence of the events in Chechnya on the terror in Dagestan is evident. During these years, according to the site of the Caucasian Knot (Dagestan: Terror Chronicle (1996–2018), 2018), foreigners appear among the militants killed in combat clashes. From 2010 to 2013 several explosions are carried out by suicide bombers, possibly due to the reactivation of the battalion of suicide bombers by Doku Umarov in 2009 (O’Loughlin at al., 2011). But still this reason seems to be less significant. First, bandit groups are generally created on a territorial basis (Pashchenko, 2012), and under the conditions of Dagestan, these groups are mostly mono-ethnic. Secondly, the influx of militants with combat experience should have increased the effectiveness of terrorist actions, though in reality, this was not observed (Table

A possible increase in the financing of terrorist groups in Dagestan from abroad in the years under consideration is also unlikely, since during this period there was an increase in the number of attempted murders related to extortion of money to finance terrorist activities.

Conclusion

The analysis showed that unemployment, a low standard of living and the diffusion of Chechen terrorists had little effect on terrorist activity in Dagestan during the period under review.

Thus, we can put forward the following hypothesis concerning the reasons for the increasing appeal of the ideas of extremism and terrorism among the youth of Dagestan in 2008–2011:

By this time, the entire generation has matured, the basis of whose world outlook was religion (young people born from about 1988 to 1993).

In the conditions of growing inequality, urbanization and high expectations, radical religious structures managed to explicate their ideas to young people stating that apostates from the true faith, corrupt government, and others are to blame in all their troubles.

The use of mathematical modeling makes it possible to obtain additional information on the mechanism for the change in terrorist activity.

References

- Antonyan, Y. (2004). The nature of ethnoreligious terrorism. Russian investigator, 6, 13–19.

- Bakker, E. (2012). Forecasting Terrorism: The Need for a More Systematic Approach. Journal of Strategic Security, 5(4), 69–84.

- Basaeva, E. K., Kamenetsky, E. S., Hosaeva, Z. Kh. (2015). Quantitative assessment of background social tension. Information Wars, 2, 25–28.

- Basaeva, E. K., Kamenetsky, E. S., Hosaeva, Z. Kh. (2017). Terrorist activity in the the Kabardino-Balkarian Republic at the beginning of the XXI century. Expert Advisory Bulletin, 2, 149–155.

- Beck, C. J. (2008). The Contribution of Social Movement Theory to Understanding Terrorism. Sociology Compass, 2(5), 1565-1581.

- Daskon, Ch. (2016). Is Terrorism the Result of Root Causes such as Poverty, Oppression and Exclusion? International Journal of Research in Sociology and Anthropology (IJRSA), 2(2), 26–33.

- Dobaev, I. P. (2009). Modern terrorism in the North Caucasus. Problems of national strategy, 1, 78–93.

- Dobaev, I. P., Dobaev, A. I. (2017). The radicalization of Islam and the security policy of Russia in the ideological sphere in the North Caucasus. Countering terrorism. Problems of the XXI century, 2, 8–15.

- Ehrlich, P. R., Liu, J. (2002). Some Roots of Terrorism. Population and Environment, 24(2), 183–192. DOI: DOI:

- Kavkazskiy uzel. (2018). Dagestan: The Chronicle of Terror (1996–2018). Retrieved from: https://www.kavkaz-uzel.eu/arti cles/73122 /

- Krueger, A. B., Malečkova, J. (2003). Education, Poverty and Terrorism: Is There a Causal Connection? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 17(4), 119 –144.

- Lee, A. (2011). Who Becomes a Terrorist? Poverty, Education, and the Origins of Political Violence. World Politics, 63(2), 203–245.

- Metelev, S. E. (2008). Modern terrorism and methods of anti-terrorism activities. Omsk: Omsk Institute (branch) RSUTE.

- Muslimov, S. Sh. (2011). The youth of Dagestan about religious and political extremism and terrorism. Sociological studies, 11, 42–47.

- O’Loughlin, J., Holland, E. C., Witmer, F. D. W. (2011). The changing geography of violence in Russia’s North Caucasus, 1999 – 2011: regional trends and local dynamics in Dagestan, Ingushetia, and Kabardino-Balkaria. Eurasian Geography and Economics, 52(5), 1–30.

- Ola, T. P. (2015). Re-Thinking Poverty, Inequality and Their Relationship to Terrorism. International Journal of Sciences: Basic and Applied Research (IJSBAR), 21(2), 264–292.

- Pashchenko, I. V. (2012). Subversive and terrorist underground as a threat to the modernization of the North Caucasus. In the materials of the Enlarged Meeting of the Scientific Council of ISEGI SSC RAS The realities of a multi-layered macro region: the potential for renewal and obstacles to development (p. 71–80). Rostov-on-Don: SSC RAS.

- Shegaev, I. S. (2017). Terrorist recruitment: degree of scientific elaboration (on materials of open dissertation research). Counter-terrorism problems of the XXI century, 2, 21–26.

- Sushchy, S. Ya. (2009). Demography and resettlement of the peoples of the North Caucasus: realities and prospects (modernization and transformation processes). Rostov-on-Don: Publishing House of the SSC.

- Sushchy, S. Ya. (2013). The North Caucasus: Realities, problems, prospects of the first third of the XXI century. Moscow: LENAND.

- Vnukova, L. B., Chelpanova, D. D., Pashchenko, I. V. (2014). Socio-political tensions in the polyethnic region. Rostov-on-Don, SSC RAS.

- Zahedzadeh, G. (2017). Containing Terrorism: A Dynamic Model. Journal of Strategic Security, 10(2), 48–59.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

29 March 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-057-0

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

58

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2787

Subjects

Sociolinguistics, linguistics, semantics, discourse analysis, science, technology, society

Cite this article as:

Basaeva, E. K., Kamenetsky, E. S., & Khosaeva, Z. K. (2019). Terrorist Activity In Dagestan At Beginning Of 21st Century. In D. K. Bataev (Ed.), Social and Cultural Transformations in the Context of Modern Globalism, vol 58. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 164-174). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.03.02.20