Abstract

Background: The need for evidence-based policy making and for processes to better inform policy making has been deeply discussed in the past decades. To this aim, a Delphi process was implemented among the countries participating in the REPOPA project, including Romania, to validate, contextualise and implement with stakeholders four thematic sets of measurable indicators for evidence-informed policy making (EIPM). Methods: A half-a-day national conference (2016) preceded by two internet-based Delphi questionnaires (2015) were implemented in Romania as part of the Delphi process. A total of 8 experts participating in the national conference were chosen based on their expertise: sport for all, health promotion/public health, political sciences, education. The role of the experts was to analyse the sets of indicators, reach consensus and give recommendations for physical activity EIPM. Results: 23 indicators grouped in 4 sets were submitted to SWOT analysis and mapped to policy phases during the national conference. ‘Communication and Participation’ set was clearly linked to the need of a comprehensive mapping of resources for communication and participation in EIPM processes (human, infrastructure/ logistics etc.). Additionally, other recommendations given for the ‘Documentation’ set of indicators were: building international partnerships among organizations; funding, organizing and using scientific research for policy making. Discussion: One of the outcomes of the Romanian REPOPA Delphi process was a list of recommendations given by experts. Among other, they agreed that the sets of indicators should be used for EIMP. Mapping the resources for EIPM is the foreseen next step in order to facilitate this process.

Keywords: Evidence-informed policyDelphimeasurable indicators

Introduction

The need for evidence-informed policy making (EIPM) and for methods and initiatives to better inform policy making has been much discussed in the past decades. Evidence-informed policy making is widely promoted to be used by policy makers in order to increase the effectiveness of policies (Diamond et al., 2014; Langlois et al., 2016; World Health Organization, 2015).

Integration of research evidence into policy making has proven to increase the effectiveness of health policy decisions (Shearer, Dion, & Lavis, 2014). But the integration of evidence into policy making has also proven to be a challenge for both researchers and policy makers (Graham et al., 2006; Landry, Lamari, & Amara, 2003). Most policy makers do not have the necessary skills to recognize good data from the poor ones. Other barriers identified relate to the fact that most often research is isolated from the policy process; the policy making process is not always understood by researchers and policy makers are not so prone to invest in prevention policies (Brownson, Chriqui, & Stamatakis, 2009).

Research can be integrated in the policy making processes by using a communication and interaction system between the research and the policy parts (Brownson et al., 2009), which would facilitate the uptake and the understanding of evidence by the policy makers, but would also improve the way researchers deliver the data resulted from their research.

A method recommended in the development of policy-relevant evidence and in creating links between researchers and policy makers is the Delphi method. This is a qualitative research method, which aims to collect knowledge of a group of experts in a particular field for achieving consensus or developing a scenario (James & Warren-Forward, 2015). The Delphi method is an iterative process that consists of a series of questionnaires applied to a group of experts, usually three to four rounds, where each round is developed based on the responses received from the previous round (Somerville, 2008). The modified Delphi technique might bring in the process face-to-face meetings before the questionnaire round(s) (e.g. focus groups or nominal group technique for informing the questionnaire used in the first round) and face-to-face meetings of the stakeholders, as the last round of the process (Landeta, 2006). Some of the Delphi method advantages are the anonymity of the responders, the opportunity of adapting their responses from round to round based on the feedback received from the whole group (Gupta & Clarke, 1996) and fostering a process of co-production of knowledge. Also, another advantage is the independent formulation of the answers, avoiding undesired effects stakeholders might have during a direct interaction – inhibition, judgement, interaction between strong personalities (Landeta, 2006).

The project REPOPA (“REsearch into POlicy to enhance Physical Activity”), funded by the European Commission, focused on the objective of developing policy briefs and guidance resources to foster EIPM as a final research outcome (Aro et al., 2016a). The project was implemented by a consortium of 10 institutions from seven countries: Denmark, The Netherlands, Finland, Romania, Italy, United Kingdom and Canada (Project REPOPA, 2015).

Within REPOPA Work Package 4 – Implementation and guidance development (led by the National Research Council of Italy), Delphi method was applied in all REPOPA partner countries to build and contextualise a set of measurable indicators that can be used for the evidence-informed policy making, in particular in the health field (Tudisca et al., 2016a; Valente et al., 2016; Valente & Aro, 2016; Tudisca et al., 2018).

Problem Statement

The gap between research and policy has been identified as a barrier for evidence-informed policy making. A better collaboration between stakeholders from the two fields would facilitate the development and implementation of evidence-informed policies. To this end, methods for fostering the interaction between the two groups mentioned above have been explored.

Research Questions

Can a Delphi process, as a tool for collaboration of research and policy stakeholders, facilitate the development of an instrument for evidence-informed policy making in public health and physical activity domains?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the study was to contextualise and further validate with the Romanian stakeholders four thematic sets of measurable indicators for EIPM, developed during previous two internet-based Delphi rounds conducted at international level. The aim of the national conference was to map indicators to one or more policy phases where they would be most useful. The indicators were meant to be used for the evidence-informed policy making in the field of public health and physical activity, with the purpose of inferring if and to what extent a health policy is evidence-informed.

Research Methods

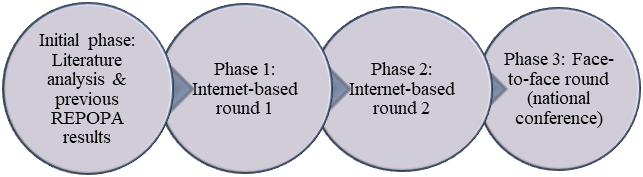

The Delphi methodology was used for developing and validating a set of measurable indicators (to be) used in health and physical activity policy making (Gupta & Clarke, 1996; Linstone & Turoff, 2002). Two internet-based Delphi questionnaires (2015) followed by a half-a-day national conference (2016) were implemented in Romania and the other partner countries, as part of the REPOPA project (Tudisca et al., 2018). In this section, the methodology used for (1) the Delphi process conducted at international consortium level and for (2) the Romanian national conference will be described.

The REPOPA research team developed an initial set of indicators meant to infer if and to what extent a health policy is evidence-informed, using a literature review process and results from previous phases of the REPOPA project. The indicators were grouped in four thematic sets: ‘Human resources’, ‘Documentation’, ‘Communication & Participation’ and ‘Monitoring & Evaluation’, to be validated at international level and contextualised at the national level in each REPOPA partner country.

Twelve Romanian panellists took part in the online Delphi process (phases one and two from Figure

The third face-to-face Delphi round consisted in a national conference preceded by an online pre-conference exercise where the final set of indicators (following the two internet-based Delphi rounds) were contextualised and further validated by national experts in each country (Aro et al., 2016b; Tudisca et al., 2016b). The aim of the national conference was to map the indicators to one or more policy phases where they would be most useful in each country setting (Tudisca et al., 2018). The mapping process started with an online pre-conference questionnaire. For an indicator to be mapped to a policy phase, at least two thirds of the participants had to directly attribute it to that specific phase(s). The indicators that did not reach consensus during the online exercise were discussed and mapped during the face-to-face meeting (Valente et al., 2016). Then, a SWOT (Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities and Threats) analysis was applied to each thematic set of indicators to identify negative and positive factors of the use of the indicators. From the total of thirty six panellists invited, eight experts participated in the Romanian national conference (one panellist participated in all three Delphi phases); they were chosen based on their expertise – they represented the following fields: sport for all, health promotion/public health, political sciences, education. The role of the experts was to analyse the sets of indicators, reach consensus and give recommendations for physical activity evidence-informed policy making.

Findings

In this section, we will present the results from the third phase of the Delphi process: the Romanian national conference held in Bucharest, in 2016. During the Romanian national conference, the 25 indicators validated by the two internet-based Delphi rounds, grouped in four thematic domains – ‘Human resources’, ‘Documentation’, ‘Communication & Participation’ and ‘Monitoring & Evaluation’ –were mapped to four theoretical policy phases (agenda setting, policy formulation, policy implementation and policy evaluation) (Dye, 2012) and were subject to a SWOT analysis. This was done to adapt the results of the first two-questionnaire international Delphi rounds to the national context. This paper will focus on two out of the four thematic domains – ‘Human resources’ and ‘Documentation’.

Table

After the panellists reached consensus for all the 25 indicators emerged by the two internet-based Delphi rounds, a SWOT exercise was proposed with the purpose of bringing the contextualisation process of the sets of indicators closer to the Romanian policy making context. During the SWOT exercise, the panellists identified strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats for the use in practice (i.e. in EIPM- related activities) of each indicator. At the end, the panellists proposed a set of recommendations on how to turn the weak aspects into strengths and how to tackle the threats. Table

Conclusion

In this study, we contextualised and further validated with the Romanian stakeholders four thematic sets of measurable indicators for EIPM, developed during previous two internet-based Delphi rounds conducted at international level. The set of contextualised indicators was promoted, as part of the REPOPA Project, as a guidance tool to increase EIPM in the field of public health and physical activity.

The implemented Delphi was a participatory approach to working with possible solutions for ensuring evidence-informed policy making, involving both researchers and policy makers in the decision-making process. The REPOPA study and more specifically the national conference implemented shows that this methodology can be successfully applied in the national Romanian context, without major differences compared to other implemented studies (Boulkedid, Abdoul, Loustau, Sibony, & Alberti, 2011; Gupta & Clarke, 1996; Hung, Altschuld, & Lee, 2008) and can be a facilitator of collaboration between stakeholders within the context of EIPM (Bertram, Loncarevic, Castellani, Gulis, & Aro, 2015).

The indicators proposed and contextualised to the national specifics ensured the evidence-informed policy making since the beginning of the process, from the agenda setting phase throughout the following policy development and implementation phases. The last phase of the process, the policy evaluation, has a high importance as well, as it could be the base line for future policy development and it could be considered evidence in future agenda setting phases.

As shown by the results of the Romanian national conference, most of the indicators from the ‘Human resources’ and ‘Documentation’ sets were mapped in the agenda setting, policy formulation and policy evaluation phases. The panellists agreed that the role of evidence was most needed in the three policy phases mentioned above, out of the total four.

To this end, some of the most important recommendations given by the Romanian panellists for the two sets of indicators presented in the ‘Results’ section concerned the development of the human resources directly responsible with the policy making process. Also, strengthening the link of the policy making institutions with the research ones has been given as a recommendation. One step to reach the above mentioned recommendations would be to allocate budget for the training of the human resources in the policy making field to better understand research. Nonetheless, this kind of training could also be implemented for the researchers, who need to be able to present their data and results in a less technical manner, so that policy makers and other stakeholders can use it. Also, panellists suggested that a clearer and long-term institutional strategy and an inter-ministerial communication protocol would be positive in the evidence-informed policy making process. The politics involved at the institutional level and the changes that occur periodically disrupt the continuation of the strategies adopted throughout one mandate. This is also the reason for which some of the policies do not reach the last phase of evaluation, thus the efficacy of the policies remains unknown. Finally, the collaboration between the public institutions and the research ones would facilitate the adoption of evidence-informed policy making and the adoption of the result evaluation culture.

The national conference implemented in Romania has received good feedback from the stakeholders involved in the study. Even if inter-institutional agreement between the institutions involved are not in place, experiences as the Delphi national conference create links between policy makers and researchers working in connected fields.

Acknowledgments

The Research into POlicy into Physical Activity (REPOPA) project has received funding by the European Union Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007-2013); Grant agreement no. 281532. This document reflects only the authors’ views and neither the European Commission nor any person on its behalf is liable for any use that may be made of the information contained herein.

References

- Aro, A., Bertram, M., Hämäläinen, R.-M., Van De Goor, I., Skovgaard, T., Valente, A., … Edwards, N. (2016a). Integrating research evidence and physical activity policy making – REPOPA project. Health Promotion International, 31(2), 430-439.

- Aro, A. R., Tudisca, V., Radl-Karimi, C., Lau, C. J., Bertram, M., Syed, A. M., … Valente, A. (2016b). Contextualization of indicators for evidence-informed policy making: Results from Denmark and Italy. European Journal of Public Health, 26(1 Suppl.), 115-116.

- Bertram, M., Loncarevic, N., Castellani, T., Gulis, G., & Aro, A. R. (2015). How could we start to develop indicators for evidence-informed policy making in public health and health promotion? Health Systems and Policy Research, 2(1), 1-4.

- Boulkedid, R., Abdoul, H., Loustau, M., Sibony, O., & Alberti, C. (2011). Using and reporting the Delphi method for selecting healthcare quality indicators: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 6(6), e20476. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0020476

- Brownson, R. C., Chriqui, J. F., & Stamatakis, K. A. (2009). Understanding evidence-based public health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 99(9), 1576-1583.

- Diamond, I. R., Grant, R. C., Feldman, B. M., Pencharz, P. B., Ling, S. C., Moore, A. M., & Wales, P. W. (2014). Defining consensus: A systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(4), 401-409.

- Dye, T. R. (2012). Understanding public policy. N.J.: Longman Publishing Group.

- Graham, I., Logan, J., Harrison, M., Straus, S., Tetroe, J., Caswell, W., & Robinson, N. (2006). Lost in knowledge translation: Time for a map? The Journal of Continuing Education in the Health Professions, 26(1), 13-24.

- Gupta, U. G., & Clarke, R. E. (1996). Theory and applications of the Delphi technique: A bibliography (1975-1994). Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 53(2), 185-211.

- Hung, H. L., Altschuld, J. W., & Lee, Y. F. (2008). Methodological and conceptual issues confronting a cross-country Delphi study of educational program evaluation. Evaluation and Program Planning, 31(2), 191-198.

- James, D., & Warren-Forward, H. (2015). Research methods for formal consensus development. Nurse Researcher, 22(3), 35-40.

- Landeta, J. (2006). Current validity of the Delphi method in social sciences. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 73(5), 467-482.

- Landry, R., Lamari, M., & Amara, N. (2003). The extent and determinants of the utilization of university research in government agencies. Public Administration Review, 63(2), 192-205.

- Langlois, E. V., Becerril Montekio, V., Young, T., Song, K., Alcalde-Rabanal, J., & Tran, N. (2016). Enhancing evidence informed policymaking in complex health systems: Lessons from multi-site collaborative approaches. Health Research Policy and Systems, 14: 20. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-016-0089-0

- Linstone, H. A., & Turoff, M. (Eds.) (2002). The Delphi Method – Techniques and applications. Retrieved from https://web.njit.edu/~turoff/pubs/delphibook/delphibook.pdf

- Project REPOPA. (2015). Retrieved from http://www.repopa.eu/

- Shearer, J. C., Dion, M., & Lavis, J. N. (2014). Exchanging and using research evidence in health policy networks: A statistical network analysis. Implementation Science, 9(1), 1-12.

- Somerville, J. A. (2008). Effective use of the Delphi process in research: Its characteristics, strengths and limitations. Retrieved from http://docplayer.net/21500232-Effective-use-of-the-delphi-process-in-research-its-characteristics-strengths-and-limitations-1-jerry-a-somerville.html

- Tudisca, V., Castellani, T., Aro, A. R., Ståhl, T., Van de Goor, I., Radl-Karimi, C., Spitters, H., … Valente, A. (2016a). REPOPA indicators for evidence-informed policy making validated by an international Delphi study. European Journal of Public Health, 26(Suppl. 1): 114. Retrieved from ahttps://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckw167.018

- Tudisca, V., Radl-Karimi, C., Lau, C. L., Syed, A. M., Aro, A. R., & Valente, A. (2016b). Indicators for evidence-informed policy making and policy phases in the Italian and Danish context. European Journal of Public Health, 26(Supppl. 1), 361-362.

- Tudisca, V., & Valente, A. (2016). Design and implemetation of an online Delphi study to develop indicators for evidence-informed policy making. Roma: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, Istituto di Ricerche Sulla Popolazione e le Politiche Sociali. (IRPPS Working papers n. 88/2016). Retrieved from file:///C:/Users/Admin/Downloads/192-608-2-PB.pdf

- Tudisca, V., Valente, A., Castellani, T., Ståhl, T., Sandu, P., Dulf, D., … Aro, A. R. (2018). Development of measurable indicators to enhance public health evidence-informed policy making (In press). Health Research Policy and Systems, 16: 47. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-018-0323-z

- Valente, A., & Aro, A. R. (2016). Frameworks and participatory processes for developing indicators for evidence-informed policy making. European Journal of Public Health, 26(Supppl. 1), 114-115.

- Valente, A., Tudisca, V., Castellani, T., Cori, L., Bianchi, F., Aro, A. R., … Jørgensen, T. (2016). Delphi-based implementation and guidance development: WP4 final report of the REsearch into POlicy to enhance Physical Activity (REPOPA) project. Retrieved from http://repopa.eu/sites/default/files/latest/D4.2.Delphi-based-implementation-guidance.pdf

- World Health Organization. (2015). Health in all policies: Training manual. Geneva: WHO Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 February 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-054-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

55

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-752

Subjects

Sports, sport science, physical education

Cite this article as:

Bozdog, M. E., Dulf, D., Sandu, P., Tudisca, V., Valente, A., Aro, A. R., & Mircea Cherecheș, R. (2019). Role Of Measurable Indicators In Evidence-Informed Policy Making –Romanian Case Study. In V. Grigore, M. Stănescu, M. Stoicescu, & L. Popescu (Eds.), Education and Sports Science in the 21st Century, vol 55. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 552-559). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.69