Abstract

The handball game is practiced at a fairly high level in almost all the countries of Europe. The less good evolution of the Romanian Men’s National Team brings us to the question: What are we doing wrong? The good results obtained by the national teams of France, Germany and Denmark in the past few decades in male handball game cause us to focus on how they achieve these results. We consider that a national team has valuable players due to the efficient work at junior level. To be able to raise valuable players to senior level, one must have a well-structured junior training strategy. Consequently, we have aimed in this paper to make a comparative analysis between the tactical training models at junior level in Romania, Germany, Denmark and France. The method used is the observational study and analyses of the tactical knowledge that players must possess at junior level in order to become the best in the world. We found differences in tactical training, like the defence systems used for each age category and the objectives pursued to implement them. We have found that, comparing the competition system from our country to theirs, they have another competition system that is based on players’ level of knowledge.

Keywords: Handballtactical trainingmodel

Introduction

Tactical training is the element of the sports training where the acquired technical skills and the player’s level of skill mastery during the game are taken advantage of. Tactics tells us the purpose for which they have been used and why we need to use technical knowledge.

Through tactics, the player’s thinking is exploited during the game in order to achieve good results. Essentially, tactical training refers to the way in which the player needs to know how to get organized, prepare and implement actions in the attack and defence phases (Cercel, 1983).

The analysis of the participation in international junior competitions shows the existence of game styles that take into account the specific motor ability of the players in each country.

Insofar as the game tactics applied during matches is involved, differentiated aspects come out on the defence and attack phases.

In the defence phase, defence systems are well-resourced, and each team, according to the age category, needs to know a certain defence system. This defence system also applies in official games. In some competitions, the way in which the team has to use defence systems is specified in the rules of the game. It has been noted lately that the focus is on the aggressive defence phase. This defence is learned correctly and complies with the rules. During learning, the placement of players and the possibility of causing the opponent to make mistakes and thus take the ball and counterattack are considered.

During the attack phase, players apply easily technical procedures with both hands. The acquired technical procedures are applied in the game in tactical action systems between two or three players. Collective tactical combinations are less used by far. The stress is laid on the continuity of passing the ball and finding solutions from optimal positions that can be completed with goal scoring.

Problem Statement

Trends in the handball game at junior and youth levels

According to statistical analyses of the European Handball Championships at the level of national youth and junior teams, the following trends in the handball game are noted:

Players are complex, they are endowed with well-developed motor skills. They have acquired various technical elements and procedures that they effectively apply during the game. Each team has two or three impressive players; (Pollany, 2016)

For the teams who participated in the European Championship in 2016, it can be noted that the 5 + 1 or 6: 0 defence systems are applied in defence. The teams had players specialised in the defence phase. Thus, 2-3 players went back and forth between the attack and defence phases.

In the attack phase, all teams started with a 3-3 attack, which, in many cases, turned to 4-2. The change is accomplished by moving the wings or transforming the backcourt or centre player into the second pivot. The game of the players without the ball can be noticed.

Regarding the individual technique, one can notice a tendency towards bilateral development, the individual technique being used on both sides of the body.

It is noted that some teams are making the difference by the efficiency of long throws, and other teams make the difference by the efficiency of sideline throws (Pollany, 2016).

According to statistical analyses, handball schools that have achieved good results over time manage to maintain the same standards, even if there are other generations of players. Young players manage to complete the generation of senior players. It has been noticed that, in recent years, the teams of France, Germany, Denmark and Spain achieved good results both at senior and junior levels. (Kovacs, 2018)

Trends in the handball game at senior level

At the level of national teams qualified for the European Men’s Handball Championship, 2018, held in Croatia, one can notice the following:

Within numerical superiority, teams use the following actions:

The centre player goes with and without the ball on the same or opposite side by passing the ball to the left or right of the backcourt player;

There are two lines of players;

The intention is to create numerical superiority either on the right side or the left side (in order for 3 to play against 2 or 2 against 1).

Within numerical inferiority, almost every team uses the temporary change of the goalkeeper to score a goal in a 6-players-against-6 situation.

Within numerical equality, the following are observed:

The use of individual actions and actions in small groups of players.

During the actions, changing the speed of execution and the pace is sought.

The game is based on simple actions.

In the attack phase, players must surprise the opponent with some new ideas.

Each team wants to score through quick throws; thus, the breaks are short, and the attacks are completed with more or less success.

It is noted that various defence systems have been used. These are: 6: 0, 5: 1, 4: 2, 5 + 1, 4 + 2, 3: 2: 1.3: 3. In choosing the defence system, we took into consideration the composition of the opposing team, the approach to the game through the prepared tactical actions and the attackers’ particularities (Kovacs, 2018);

Research Questions

Are there any similarities and differences in tactical game models between juvenile teams in Europe?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of this paper is to study the tactical training models in some European countries in order to point out the similarities and differences that exist in relation to the Romanian handball school.

We believe that the handball game in our country needs much more attention in the preparation of children and junior teams.

The appropriateness of this approach resides in an analysis of the tactical knowledge that players from different European countries have to learn. This knowledge is applied within a competitive system in which teams will participate. Knowing the tactical content and the competitive system can help us improve the game. Using the comparison method, we will compare our teaching methodology to that of other countries currently enjoying good results. Based on the analysed information, we will find some ways to improve our tactics. We will also show the handball game trends at the level of junior and youth national teams.

Research Methods

According to statistical analyses in recent decades, the national teams of France, Germany and Denmark have achieved very good results in all age categories (Kovacs, 2018).

This urges us to focus on how they achieve these results. We consider that a national team has valuable players due to the efficiency used at junior level. To be able to raise valuable players at senior level, one must have a well-structured junior training strategy.

We want to identify the model of tactical knowledge that players must hold at junior level in order to become the best in the world. The player, in addition to possessing the developed motor skills and technical skills, must be able to effectively use them at the right time during the game.

We also intend to analyse the competitive systems in the countries mentioned above. We consider that the requirements that have to be met by the competing team may also influence the team’s tactical training.

This is argued by the following:

The knowledge acquired during the attack phase should be used against the defence system applied by the opponents;

Applying the defence system required by the competition rules must be prepared in advance, in the training lessons.

Knowing the rules of the game and the requirements imposed by it; among them, we mention those related to the game system and the height or the simplified rules in Mini-handball.

The method used to analyse tactics put forth by other countries and the competitive systems practiced represent the observational study.

Findings

Analysis of competitive systems in juvenile handball in European countries

The competitive system influences the player training. In Romania, the junior competitive system is based on the teams registered in the championships, and geographically distributed groups are made up. The current competition year from juniors 3 to juniors 1 is formed by Home games – Tournament 1 and Tournament 2, and Away games, Semifinal Tournament and Final Tournament.

The participating teams must meet the age criteria and, in order to obtain a bonus point regardless of the result obtained in the match, the height-related criteria. We mention that, in our country, the junior competition has always undergone changes. Starting this year, Junior 3 must comply with the rule that, in the first half, the defence system should be advanced, an important rule that determines the game of each team (FRH, 2017).

In reply to the countries analysed comparatively, we observe that there is another competitive system, which is based on the players’ level of knowledge. This gives players the opportunity to express themselves in the game and to evolve, playing with the opponents at the same level.

In France, up to the age of 13, there is only the departmental or county championship, the same as in Romania. Between 13 and 16 years of age, regional and county championships are organized, and for the 17-18-year-olds, there are three championships: county, regional and national ones. The national level is the most powerful. There are qualification phases if a player wants to go to a higher level. There are no height criteria, but, to be eligible for a Centre of Excellence, a player must meet certain requirements.

The Danish competition system is divided into 8 regional centres, and the 8 zone centres work on planning the matches. There are competitions from the age of 4 up to the senior level. The way in which junior competitions take place depends on each team’s level of training. After each team has played in the group, the first two teams move up into the group that is ahead of them, and the team on the last place descends to the lower group. The first two teams in the A-value group, which is ranked the highest level of knowledge, will qualify for a newly formed group called the AA group.

In Denmark, all children coming to the gym are welcome to practice handball, no child is denied. According to the team’s potential, the club and coach determine at what level they can participate (Sommerturnering, 2018; Turneringsreglement øvrige, 2018; Jydsk Mesterskab 2017-2018, 2018;

The German competition system is the same as in Denmark, being divided into zones, and is called DHB, Deutscher Handballbund. Teams play in the competition at the players’ level of the knowledge.

Table

Tactical models in juvenile handball

The Romanian handball school is based on the idea that the player, after having completed the junior level, must know “All the handball”. The junior must acquire the bulk of technical and tactical knowledge provided at each stage of training. This does not imply that he/she has reached a maximum level and has nothing to improve or refine. Performance capability has also improved in seniors at the maximum skill level of the player. (Ghermănescu, 1983)

Today, in Romania, the introduction of children to handball has been lowered to the age of 6-7 years. Until the age of 18, the player will follow 12 years of sports training. Throughout these years, the player has to acquire the necessary knowledge in order to be able to play at senior level. (Negulescu et al., 2017)

In Romania, there is a model for the attack and defence phases addressed to children and juniors. This can be found on the website of the Romanian Handball Federation (FRH), but also within the vocational school program for handball (FRH, 2017).

In 2017, male teams have received a tutorial containing methodological aspects of the knowledge that each player has to acquire. It contains objectives of the individual or collective attack and defence phases. The objectives that each player must achieve in the offensive and defensive phases are mentioned. There is also a brief guidance on the methodology for implementing the specified objectives for each age category. (Fuertes, 2017)

Within the

On the website of the Romanian Handball Federation, there is also a game model for children and juniors. It contains the particularities and principles of the game by training level (Hantău, 2014; FRH, 2014a; FRH, 2014b).

We have found that, in other countries, some objectives are pursued at each age level in the training process. There is continuity in the teaching content.

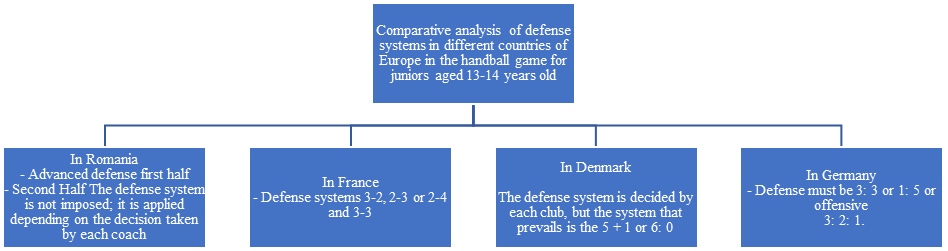

Noteworthy is the defence system that we use in relation to other European countries, which is schematically shown in Figure

-

for beginner groups, the defence systems in the 6: 0, 5 + 1 area and man-to-man are taught; -

for the advanced level, the player needs to know the combined 5 + 1, 4 + 2, 3 + 2 + 1 defence systems and man-to-man all over the court;

We can see that the winning team, the French one, scored the most goals, with a 70% rate, from more possibilities to score against the other teams. The efficiency of the throws is higher compared to the Danish team, which has a 60% rate. We can see that the vast majority of the teams finished with 9-m throws, followed by 6-m throws, sideline throws and then 7-m throws.

According to expert analysis, the teams of Germany and France were the most creative in the attack phase. Scandinavian teams showed extreme throwing power and great ability to play 1 against 1 in an attempt to pass their opponents. These two teams were the best in group and team tactics.

The French team used diagonal passes in all matches, with varied pathways, passes from the left backcourt to the right backcourt, from the left to the right wings etc. The similarity between junior and senior teams is noticed. There is continuity in the preparation of teams from the junior level to the senior level. The defence system efficiently used by the teams of France and Germany is the 5 + 1 defence system (Pollany, 2016; Kovacs, 2018).

Conclusion

There are similarities in the construction of each team, but also in the play style that each country adopts.

By comparing the tactical content adopted for the preparation of junior players in Romania, France, Denmark and Germany, the following have been found:

The technical and tactical content used at national team level does not differ greatly from the other countries mentioned in the paper.

There are different periods of time when certain technical and tactical knowledge is acquired.

It is noticed in the tactical training that:

In the defence phase, the defence systems used for children and juniors differ.

In the attack phase, the tactical content is the same, but there are differences in learning tactical action; thus, the player needs to know why to learn it and when it must be used in the game.

The junior competitive system is different, as well as the rules for juniors.

We believe that more attention should be paid to what has to be learned in order to be able to ask the players to perform during the game.

Acknowledgments

The work was done under the aegis of the National University of Physical Education and Sport in Bucharest.

References

- Cercel, P. (1983). Handbal – Antrenamentul echipelor masculine. Bucureşti: Sport-Turism.

- EHF. (2016a). M 18 Euro 2016, 11-21 August 2016, Croatia, Cumulative team statistics. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyses/2016/CRO/2/1/02.Croatia.pdf

- EHF. (2016b). M 18 Euro 2016, 11-21 August 2016, Denmark, Cumulative team statistics. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyses/2016/CRO/2/1/05.Denmark.pdf

- EHF. (2016c). M 18 Euro 2016, 11-21 August 2016, France, Cumulative team statistics. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyses/2016/CRO/2/1/01.France.pdf

- EHF. (2016d). M 18 Euro 2016, 11-21 August 2016, Germany, Cumulative team statistics. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyses/2016/CRO/2/1/03.Germany.pdf

- EHF. (2016e). M 18 Euro 2016, 11-21 August 2016, Slovenia, Cumulative team statistics. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyes/2016/CRO/2/1/04.Slovenia.pdf

- FRH. (2017). Conținutul tehnico-tactic și dezvoltarea calităților motrice pe niveluri de vârstă. Retrieved from http://frh.ro/img_stiri/files/Continut%20tehnico-tactic.pdf

- FRH. (2017). Regulament de desfăşurare a Campionatului Naţional de Juniori III, masculin, an competiţional 2017-2018. Retrieved from http://www.frh.ro/frh/pdf/REGULAMENT%20DE%20DESFASURARE%20JIIIM.pdf

- FRH. (2014a). Modelul jocului de handbal la copii avansați – performanță (juniori III). În Particularitățile și principiile de instruire ale jocului la nivelul juniorilor III (pp. 23-43). Retrieved from http://www.frh.ro/img_stiri/files/Modelul%20jocului%20la%20nivelul%20juniorilor%20III.pdf

- FRH. (2014b). Modelul jocului de handbal la juniori II. Retrieved from http://frh.ro/img_stiri/files/Modelul%20jocului%20la%20nivelul%20juniorilor%20II.pdf

- Fuertes, P. X. (2017). Aspecte metodologice de aplicare a concepției de joc la nivelul handbalului masculin. Retrieved from http://frh.ro/img_stiri/files/Aspecte%20metodologice%20de%20aplicare%20a%20conceptiei%20de%20joc%20la%20nivelul%20handbalului%20masculin.pdf

- Ghermănescu, I. K. (1983). Teoria şi metodica handbalului. Bucureşti: Editura Didactică şi Pedagogică.

- Hantău, C. (2014). Metodica instruirii copiilor în etapa I de pregătire. Retrieved from http://frh.ro/img_stiri/files/metodica_instruirii_copiilor_in_etapa_1.pdf

- Jydsk Mesterskab 2017/2018. (2018). Resultater for Jydsk Mesterskab 2017/2018. Retrieved from https://www.haandbold.dk/forbund/jhf-og-kreds-1-2-4/nyheder/nyheder/jydsk-mesterskab-2017-2018/

- Kovacs, P. (2018). Men’s Euro 2018 Croatia, Qualitative analysis. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyses/2018/CRO/3/13TH%20MEN'S%20EHF%20EURO%202018%20CRO.pdf

- Machill, M. (2015). Jugendhandball. Regeln und Besonderheiten. Retrieved from https://www.handballkreis-guetersloh.de/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/Jugendhandball_12_2015.pdf

- Ligue de Provence Alpes de Handball. (2012). Modes de jeu et contenus: Référentiel 9-14 ans. Retrieved from http://www.asihand.com/referentiel-9-14ans

- Ministerul Educației Naționale. (2017). Programa şcolară pentru Pregătire sportivă practică învăţământ sportiv gimnazial cu program integrat. Disciplina sportivă de specializare: Handbal, Clasele a V-a a VIII-a, Grupe începători/avansați/performanță. Bucureşti: MEN. Retrieved from http://programe.ise.ro/Portals/1/Curriculum/2017-progr/87-HANDBAL%20-%205-8%20PSP.pdf

- Negulescu, I., Igorov, M., Hantău, C., Caracaș, V., Vărzaru, C., Predoiu, A., … Ionescu, V. (2017). Orientări metodice privind selecţia şi pregătirea iniţială în handbal. UNEFS Bucureşti. Retrieved from http://frh.ro/img_stiri/files/Minihandbal.pdf

- Niveaustævner. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.haandbold.dk/forbund/hroe/turneringer-staevner/staevner/niveaustaevner/

- Pollany, W. (2016). Comprehensive analysis of the EHF M20 European Championship 2016. Retrieved from http://home.eurohandball.com/ehf_files/specificHBI/ECh_Analyses/2016/DEN/3/DEN_COMPREHENSIVE%20ANALYSIS%20OF%20THE%20EHF%20M20%20EUROPEAN%20CHAMPIONSHIP%202016.pdf

- Sommerturnering. (2018). Retrieved from https://www.haandbold.dk/forbund/hroe/turneringerstaevner/turneringsinformation/sommerturnerin/

- Totalhaandbold I Foreningen, Dansk Håndbold Forbund. (2014). Retrieved from http://haandbold.dk/media/1347/totalhaandbold-i-foreningen-webudgave.pdf

- Turneringsreglement øvrige. (2018). Retrieved from https://haandbold.dk/regler-love/reglementer/turneringsreglement-oevrige-raekker/

- Turneringskalender 2017-2018-2018-2019. (2018). Retrieved from http://www.haandbold.dk/forbund/jhf-og-kreds-1-2 4/turneringerstaevner/turneringsinformation/turneringskalender-2017-2018-2018-2019/

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 February 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-054-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

55

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-752

Subjects

Sports, sport science, physical education

Cite this article as:

Romila, C., & Macovei, S. (2019). Comparative Analysis Of Tactical Models In Juvenile Handball In Countries Of Europe. In V. Grigore, M. Stănescu, M. Stoicescu, & L. Popescu (Eds.), Education and Sports Science in the 21st Century, vol 55. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 533-542). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.67