Abstract

The coach is one of the success factors of a sports career. The results of the athletes in competitions depend on his/her skill level in the field of sports training. However, studies have shown that another essential factor in the psycho-socio-professional profile of the coach is the quality of his/her life, measured in terms of the level of perceived stress and the way the coach responds to it. Thus, in the last years, the ability to cope with stress is more and more often mentioned in the framework of professional competences as a whole, being absolutely necessary for the efficiency of the activity and for maintaining the coaches’ own health. This paper aims to highlight the particularities of stress in the early coaches’ career in Romania. The study assessed the occupational stress of coaches using the Job Stress Survey (JSS) that allowed the evaluation of the perceived severity and frequency of occurrence of stress-generating situations. The questionnaire was administered, in an electronic version, to 42 coaches. Factor-related analyses of the coaches’ responses allowed us to determine three indicators: occupational stress, work pressure and lack of organisational support. We believe that the results of our study allow those who practice this profession to become aware of a number of factors favouring stress and to seek solutions to alleviate it. At the same time, the study provides important information for coaches, who are invited to provide future specialists with tools that they can constantly apply to maintain the quality of life.

Keywords: Job stressorsstress managementcoachessport

Introduction

The coach is one of the success factors of a sports carrier. The results of the athletes in competitions depend on the level of professional training of the coach. Studies have shown, however, that the coach’s life quality is another essential factor in his/her psycho-socio-professional profile, and it is measured by the level of perceived stress and how the coach responds to it. In recent years, among the professional competences, the most often mentioned one is coping with stress, which is vital for the efficiency of the activity and for maintaining one’s own health. This trend is manifested in the context of unanimous recognition of the fact that coaches are subject to the action of specific stressors. Besides, the most important occupational health challenges in the 21st century are those related to psycho-social stressors, such as information technology, overworking and work-related pressure (Tashman, Tenenbaum, & Eklund, 2010; Landsbergis, 2003).

At the same time, various studies quoted by Norris, Didymus and Kaiseler (2017) have highlighted that the well-being of coaches contributes to the creation of a positive educational and training environment, with direct benefits for athletes and their efficiency in competitions.

Under these circumstances, occupational stress management brings forth the strategies by which employees from different fields meet the demands of their occupation in order to preserve their physical and mental health. Dynamics and variety of demands are modern features of occupations in a knowledge-based society, the one that employees need to face by assimilating new skills. Thus, knowing the main sources of stress is important for the training providers too, given that they must provide future specialists with ergonomic solutions related to the practice of this occupation. There is also the issue of strategies that coaches apply for the purpose of self-regulating reactions to stress so that the efficiency of their work and their overall health are not affected. From the perspective of stress management, we noted the tendency of coaches to cope by predominantly using problem-focused strategies (Norris et al., 2017).

Problem Statement

Highlighting the stress factors of this profession is a constant concern of specialists in the field. Thelwell, Weston, Greenlees and Hutchings (2008) believe that the coach should be regarded as a performer. The multiple roles a coach plays (depending on the level of preparedness of the athletes trained by him/her), namely those of manager, counsellor, mentor and friend, require knowing the sources of stress they feel, according to the role assumed at some point.

Being a coach, especially in high performance, involves repeated exposure to a series of stress factors that may induce psychological effects expressed through various changes in the cognitive function, emotions and behaviour. The lack of behaviour able to regulate these changes may affect their health, causing a number of cardiovascular, metabolic, as well as psychopathological disorders. (Cox, Griffiths, & Rial-Gonzalez, 2000) The two most common explanatory theories of stress are in general the cognitive-emotional model of stress and burnout (Cooper & Smith, 1986), and the transactional stress theory (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). Both theories have applicability in the field of occupational stress analysis in sports.

The analysis of stress factors was made taking into account several variables. Some studies highlighted their different ratio in relation to the performance level of coaches.

In 1982, Kroll and Gundersheim showed that UK coaches working with high school students had a high level of stress, especially associated with the interpersonal relationships established with them (lack of respect from athletes). For coaches working with the Olympic teams, the main stressors were the lack of time for a thorough preparation of competitions and spending a long time away from their families (Sullivan & Nashman, 1993). In 2007, Frey highlighted as main stressors among coaches from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA), Division One, the lack of control over their athletes, the many roles they had to fulfil, the interference between professional and family life, the decrease in interest in practicing this occupation. Therefore, stress factors come from both the organisational and professional/competitive environments, acting with varying degrees of intensity throughout the coaches’ careers.

In a study published in 2012 by Stănescu, Vasiliu and Stoicescu, it was emphasised that coaches felt intensively the action of stressors, mainly associated with their professional tasks. The consequence of their action is perceived as negative, primarily in terms of professional performance, and then in terms of health and family relationships. On the other hand, professional satisfaction is appreciated with reference to the results obtained by the athletes. These results are confirmed in 2017 by Norris et al., showing that the higher the stress level, the lower the coach’s performance. The main categories of stressors were of organisational nature, related to athletic performance (coachability, professionalism, attitude and commitment), to their own performance (intrapersonal), to external pressure (families, parents, club managers) (interpersonal).

Rhind, Scott and Fletcher (2013) performed an analysis of stressors in the work of professional soccer coaches and identified 8 major themes related to the identified stressors: job role; players; manager; support staff; training environment; away matches; governance; soccer culture. The combined action of several stressors is the main risk factor for the overwork (burnout) of coaches (Norris et al., 2017).

Although the topic of occupational stress in sport is in the attention of researchers in the field, no information has been found regarding the particular characteristics of this phenomenon at the beginning of the career, compared to other stages of experience in this activity. We consider this characterisation to be important especially for the training providers, who, as pointed out above, should include some skills related to the management of specific occupational stress in their qualification programs. Also, knowing the stress factors allows the identification of specific aspects of each job, and in this way, a series of problems can be anticipated at the level of the sports organisation.

The transition from athlete to coach

This concern of the training providers should also be supported by the fact that the cessation of performance sports and the debut of a coaching career require making a series of psychological and social adaptations to the new status. Taking into account that any coach also assumes the role of manager, the transition process can be analysed in light of the seven-phase transition model proposed by Adams, Hayes and Hopson (1976). According to this model, the stress experienced by the person concerned is the consequence of his/her effort to adapt to the new job requirements.

In 1991, Turnage and Spielberg mentioned that the highest stress levels for managers were the result of frequent activity interruptions, deadlines and crisis situations. Similar events can also be found in the coach’s activity. It is easier to pass through the athlete-coach transition if this process is understood and the coach knows what to expect in terms of stress and psychological tension specific to the practice of this occupation.

Given the numerous studies addressing the issue of occupational stress and its management strategies in sport, we have identified a lack of information on these issues in the Romanian sports in general and in various sports fields, especially amongst beginner coaches.

Research Questions

Based on the literature data, we intend to investigate the particularities of occupational stress index for beginner coaches and those related to the severity and frequency of stress during the practice of this occupation. Given that most people in the target group of our study want to become football coaches, we ask about the relationship between the data from this category of graduates and those from other sports (skiing, swimming, judo, basketball, dancesport, gymnastics).

Purpose of the Study

The study aims to provide a model of occupational stress analysis in the field of sport, using information that highlights the combined characteristics, the severity and frequency of stressor occurrence. We also want to create a first referential to characterise the coaching profession, including in terms of stress factors assessed using a standardised test. Taking into consideration the particularities of each sports branch, we consider that such an analysis should be made for each sports branch of the coaching profession. Starting from the results obtained in this study, we intended to formulate recommendations to support both club managers and training providers in designing and implementing the necessary measures to maintain the efficiency of coaches’ work within the desired parameters.

Research Methods

In light of modern theory on occupational stress, it results from the complex interaction of the individual with their work environment, i.e. with the objectives of their work, with the conditions in which they carry out their activities and with all factors acting on them. Therefore, we consider that stress assessment is an insight-based process that highlights personal perceptions of professional demands, the ability to respond to these demands, professional development needs and the quality of professional relationships.

We have chosen to evaluate occupational stress with the Job Stress Survey (JSS), because it focuses on identifying work situations that often lead to psychological tension and offers, for the interpretation of results, specific scales for the Romanian population (Iliescu, Livinti, & Pitariu, 2010). To analyse the results, we used the scale designed for the Romanian normative sample, by converting gross scores into T-scores.

JSS items allow the possibility to determine the perceived severity and frequency of occurrence of 30 stress-generating situations during the last 6 months of professional activity. Surveyed people evaluate the severity of stressors on a 9-point scale, and their frequency, on a scale of 0 to 10. The result of the two characteristics is the basis for establishing the occupational stress index. JSS reveals (as specific scales) two major components of occupational stress: Job Pressure (JP) and Lack of Support (LS). The JP scale evaluates the pressures associated with the work itself, and the LS scale evaluates the pressures associated with the lack of support from supervisors, colleagues or the organisation’s policies and procedures. Therefore, JSS allowed us to establish three indicators: (Severity - S, Frequency - F and Index - X) for each of the three areas: Pressure - JP, Support - LS and General Stress - JS.

In addition, the responses were associated with the nine sub-scales: for the general stress score JS-X (occupational stress index), JS-S (stress severity) and JS-F (stress frequency), for the stress pressure JP-X (job pressure index), JP-S (pressure severity) and JP-F (frequency of pressure), and for the lack of support LS-X (lack of support index), LS-S (lack of support severity) and LS-F (lack of support frequency).

In addition to providing information on specific stressors, JSS has enabled us to identify the sources of occupational stress by determining the frequency of responses associated with each stress element/situation in the test inventory. Last but not least, the option for this test is justified by the fact that the results of its application can be the basis for designing educational interventions aimed at improving the effects of stress and increasing the stress management capacity of coaches.

Data processing was done using MS Excel’s statistical functions, namely the t-Test, to show the significance of differences between the respondents’ averages in each stress-generating situation, and the ANOVA test, for the significance of differences between the gross/general scores of stress indicators. Beginner football coaches were compared to those in other branches and coaches in the Romanian sample (total sample).

Target group

The test was applied electronically to 42 starting coaches, of whom 34 men and 8 women responded (21 with football specialisation and 21 with specialisation in other sports fields). These coaches were graduates of the “Ioan Kunst-Ghermănescu” Post-Secondary School for Coaches (Bucharest), during their first two years of activity after graduation, and were employed in various private sports clubs.

The choice of this target group has also been determined by the fact that coaches who are trained at the post-secondary school during the 2-year program show a number of special characteristics: 75% of them are former professional athletes and high performance athletes; 50 to 85% were or still are football players; the average age is 34.21 years; 80% are trained as instructors (ISCED 3) in various training activities for groups of athletes with different ages and levels of training.

Findings

Analysis of stress indicators

A first report of the obtained results was made against the T-score cut-off (T = 60) recommended for data analysis (Spielberger & Vagg, 2010). Table

Most T-scores with values greater than 50 indicate an average level of occupational stress, with an increasing trend, as the values approach 60. This result draws attention to the fact that even in the early years of career, coaches, regardless of the sports branch, feel the job pressure, as well as the lack of organisational support, illustrated mainly by the relationship-linked difficulties (subchapter 6.2.).

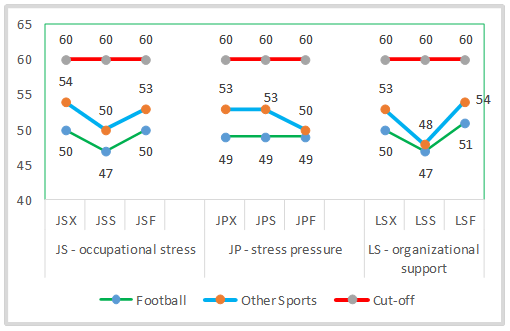

Regarding the occupational stress experienced by football coaches compared to coaches from other sports, we have found that the level is lower for all the indicators (Figure

The share of stress factors

The processing of JSS results, in relation to the severity and frequency with which employees thought about the stress-generating situations, took into account the scales of job pressure and lack of support (Spielberger & Vagg, 2010). The analysis focused on these aspects for beginner coaches in general, and then in comparison with those specialised in football and those specialised in other sports. The analysis included only the cases where the average level of stress was exceeded, namely the value 5.

The analysis of stress-generating situations for beginner coaches is shown in Table

As far as football coaches are concerned, situations with the highest stress-generating potential are: inadequate salary, bureaucracy linked to the planning documents they have to prepare, the poor motivation of their peers. As regards the frequency of feeling stressful situations, the inappropriate salary remains the main stressor, followed by the shortage of staff and the increased responsibility in terms of job tasks (Table

Beginner coaches in other sporting sectors tend to feel more intensely the non-fulfilment of job-related tasks by other colleagues, inadequate salary and the need to make quick decisions. However, in terms of frequency, the most acutely felt issues are: salary, distribution of less pleasant tasks, high responsibility, carrying out tasks not provided in the job description. (Table

Although the average stress scores obtained for each situation are not significantly different between football and the other sports (the t-value at p = 0.05 is -1.9, compared to critical t = 2), we note that the organisational stressor represented by inadequate salary is felt most strongly. The other stressors are related, to the same extent, to the specific characteristics of the professional activity (JP) and that of the sports organisation (LS).

Conclusion

The JSS application allowed us to perform an integrated analysis on the three parameters of the occupational stress analysis: severity, frequency and general stress index, from the perspective of the two scales: work pressure (JP) and lack of organisational support (LS).

Given that in the literature which refers to the application of this test, there is no data resulted from its application to the population belonging to our target group, i.e. starting coaches, the comparison of the results of our study was made intragroup and intergroup, with the normative sample for Romania.

The strongest stressors come from the organisational category, regardless of the sports field. The low salary of the beginner coach is the major stressor. This aspect can be related to the social status of the coach, who begins both his/her professional career and family life.

In a previous study, in 2011, we highlight that low salary remains a problem for most coaches throughout their careers, but the high level of stress in coaches with more than 10 years of seniority is linked to their professional activities (Stănescu, Vasiliu, & Stoicescu, 2012). No other studies in international literature mention salary among the stress factors. Subjects in the respective target groups feel more strongly the category of stressors targeting interpersonal relationships and those related to the results of the athletes in competitions (Olusoga, Butt, Hays, & Maynard, 2009; Frey, 2007).

The low salary level mentioned by the coaches included in this research study may also be the cause of the low motivation for practising this occupation, as well as the lack of involvement in solving professional attributions, facts recalled by football coaches as identified with their colleagues. Thus, we can say that the organisational stress factors can influence the quality of coaches’ work. These results are in line with the conclusions of the studies mentioned above.

On the other hand, the frequent high-responsibility tasks assumed by coaches in other sports fields (skiing, swimming, judo, basketball, dancesport, gymnastics) may be associated with the pressure to obtain good results in competitions. This stressor related to the professional activity also appears in coaches, regardless of their seniority in this occupation, along with the one regarding the drawing up of the planning documents (Stănescu, Vasiliu, & Stoicescu, 2012). This stressor is strongly conditioned by the competition system organised at the level of the national sports federation. The more the emphasis is placed on getting results in competitions at younger ages, the more the stress related to this situation will increase for beginner coaches.

Given that the main stressors are of organisational nature, we believe that the measures to optimise the training level of coaches so that they acquire additional competencies should be accompanied by economic measures ready to be implemented in all sports fields. We also recommend the involvement of beginner coaches in the decision-making process through consultation on issues related to their status, the content of their work and the reward system implemented within the organisation.

Taking into account these results, we believe that the training programs for coaches (ISCED 5) should focus on the training of professional skills (scheduling, planning, training, evaluation), which ensures the long-term association of professional effort with the satisfaction meant to maintain career motivation. At the same time, we believe that transversal competencies, especially communication and group work, are important in order to ensure a good level of adaptation to job requirements, especially in the first years of practice.

Therefore, similar attention paid to the skills pertaining only to coaches and those that are common to other occupations provides prerequisites for the optimal professional adaptation of young specialists to specific demands. We believe that the training standard for coaches should focus on education too, namely on identifying and understanding the action of stressors on the effectiveness of the coaches’ work and wellbeing.

Given the assessment tool used (JSS), we expect certain variability in terms of responses, because only the consequences of the stressor action in the last six months of professional activity have been measured. Moreover, researchers must identify the particularities of stress manifestation in the coaches’ work, according to gender, experience, level of performance, results, specific nature of the sport field in which they work. We suggest creating a scale of action for stressors for the sports industries, so that specific recommendations can be made in the framework of a monograph of this occupation.

Acknowledgments

References

- Adams, J. D., Hayes, J., & Hopson, B. (1976). Transition: Understanding and managing personal change. London: Martin Robertson.

- Cox, T., Griffiths, A., & Rial-Gonzalez, E. (2000). Research on work-related stress. Luxembourg: European Agency for Safety and Health at Work.

- Cooper, C. L., & Smith, M. J. (1986). Job stress and Blue Collar work. Chichester: Wiley & Sons.

- Frey, M. (2007). College coaches’ experiences with stress – “Problem solvers” have problems too. The Sport Psychologist, 21(1), 38-57.

- Iliescu, D., Livinti, R., & Pitariu, H. (2010). Adaptarea Job Stress Survey (JSS) în România: Implicații privind manifestări ale stresului ocupațional în România. Psihologia Resurselor Umane, 8(1), 27-38.

- Kroll, W., & Gundersheim, J. (1982). Stress factors in coaching. Coaching Science Update, 23, 47-49.

- Landsbergis, P. A. (2003). The changing organization of work and the safety and health of working people: A commentary. Journal of Occupational Environmental Medicine, 45(1), 61-72.

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. New York: Springer Publications.

- Norris, L. A., Didymus, F. F., & Kaiseler, M. (2017). Stressors, coping and well-being among sports coaches: A systematic review. Psychology of Sport & Exercise, 33, 93-112.

- Olusoga, P., Butt, J., Hays, K. & Maynard, I. (2009). Stress in elite sports coaching: Identifying stressors. Journal of Applied Sport Psychology, 21(4), 442-459.

- Rhind, D. J. A., Scott, M., & Fletcher, D. (2013). Organizational stress in professional soccer coaches. International Journal of Sport Psychology, 44(1), 1-16.

- Spielberger, C. D., & Vagg, P. R. (2010). Job Stress Survey (JSS) – Manual tehnic. Cluj Napoca: Sinapsis.

- Spielberger, C. D., & Vagg, P. R. (1999). Test manual for the Job Stress Survey (JSS). Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Stănescu, M., Vasiliu, A. M., & Stoicescu, M. (2012). Occupational stress in physical education and sport area. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 33, 218-222. Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.01.115

- Sullivan, P. A., & Nashman H. W. (1993). The 1992 United States Olympic team sport coaches: Satisfactions and concerns. Applied Research in Coaching and Athletics Annual, 8, 1-14.

- Tashman, L. S., Tenenbaum, G., & Eklund, R. (2010). The effect of perceived stress on the relationship between perfectionism and burnout in coaches. Anxiety, Stress and Coping, 23(2), 195-212.

- Thelwell, R. C., Weston, N. J. V., Greenlees, I. A., & Hutchings, N. V. (2008). A qualitative exploration of psychological-skills use in coaches. The Sport Psychologist, 22(1), 38-53.

- Turnage, J. J., & Spielberger, C. D. (1991). Job stress in managers, professionals and clerical workers. Work & Stress – An International Journal of Work, Health & Organisations, 5(3), 165-176.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 February 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-054-9

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

55

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-752

Subjects

Sports, sport science, physical education

Cite this article as:

Stănescu, M., & Stoicescu, M. (2019). Managing The Occupational Stress In Early Coaches’ Career. In V. Grigore, M. Stănescu, M. Stoicescu, & L. Popescu (Eds.), Education and Sports Science in the 21st Century, vol 55. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 26-36). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.02.4