Abstract

Communication is an inevitable element in social interaction between people. The key role, either negative or positive, in the development of children’s speech is played by parents as well as teachers. The developed mother tongue can be an advantage or disadvantage for a child when starting school. The mother tongue is the language children learn as the first one in the process of socialization (

Keywords: Communication skillsmother tonguelanguage competencesocially disadvantaged environment

Introduction

Communication is a person’s ability to use the means of expressions not only to exchange various types of information, but also to create, maintain and nurture interpersonal relationships. It is one of the most important tools of learning and is connected with the development of social skills. If individuals are not able to communicate, they cannot express their wishes, needs, agreement or disagreement, or participate in social communication. Furthermore, they can have difficulties in comprehension. Often, it leads to feelings of anxiety, fear, confusion and frustration which can result in outbursts of anger or aggression.

After birth, children develop in certain environments. Children acquire not only basic hygiene habits, walking, language, but also thinking, values, ideals, attitudes, habits, communication skills, and knowledge about nature and people in society. During their primary socialization, children acquire these values, attitudes, norms, and language in the communication form through their parents, siblings, relatives, and later through peers in their natural environment. The mother tongue is an inevitable element in social interaction between people. The developed mother tongue is an advantage for a child when starting school. The mother tongue is the language children learn as the first one in the process of socialization (Lemhöfer, Schriefers, & Hanique, 2010), the language children have learnt in their life, and which influences their future. Also, Basil Bernstein (1971) considers a language the main means of person’s socialization, and emphasizes a direct relationship between a social group and a language.

We concur with authors such as Říčan (1991), Plaňava (1994), Říčan (2003), Walsh (1982), and Prúcha, Mareš, & Walterová (2003) who focused their studies on families with children, and developed an essence of social status of the family in society. The family has several important functions, including biological, economic, social, and psychological. The family is considered a mediator of recognized values; the first control organ of meeting the norms, and a mediator of the cultural archetype. It is also considered a basic social unit. A correctly set structure system in the family is one of the most important determinants of child’s personality development, in which they grow up, where they acquire role models of behaviour and action, the first models of communication with others, and learn to act in accordance with the set norms of society and be responsible for their action. Children growing up in Roma families, as some authors such as Légiose (1995), Horváthová, (2002), and Portik (2003) state, have always been considered the basis of a family, which they prove by their study findings that a biologically-reproductive function is characteristic for Roma families. These findings are confirmed also by Šikrová (2004) who states that half of seven or eight million Roma are school-age children. According to Pape (2007), Roma children are the objects of permanent attention in their family environment; in the context of the family they learn through observation and imitation, which means children learn social interaction, and learn to speak the Romani mother tongue. The Romani language, as Cina & Cinová (2010) state, is one of the basic elements of the Roma ethnic group; Roma use it for communication anywhere in the world, even though they communicate in different dialects.

The Slovak context

We agree with Rosinský (2009) that Romani children start school at the age of six years, they do so in an unknown sometimes even unfriendly environment which they have to navigate on their own, without their parents who had always been there for them. This situation is made worse as many schools in Slovakia have no Roma teachers and teaching aids and textbook contents and designs are all adapted for children whose mother tongue is Slovak, Traditional Roma family education does not prepare the children to the standards that teachers expect from an average pupil in the first year” (paraphrased by the authors). Teachers in the first year of primary schools must be able to struggle with children’s communication tactics learnt before starting school. In terms of the fundamental communication skills, children are expected to have clear and comprehensible speech, be able to communicate and express themselves fluently, pay attention and focus on a certain activity. Our study captures the reality about the lack of progress in communication skills in sentence building in the second testing at the end of the school year in children whose mother tongue is Romani in comparison with children whose mother tongue is Slovak.

School as an inequitable environment

In this context it is necessary to say that many sociological experts state that schooling and education systems are supporters of - if not directly tools of - social inequalities. The most significant and world-renowned of these are Basil Bernstein and Pierre Bourdieu (1990).

Bernstein (1971) in his book “Class, Codes and Control” developed his theory about reproduction of social inequalities through the education system based on analysis of the relationship between a school system and a way of communication in France. His theory is based on the existence of two types of language codes (restricted and elaborated) that are obtained by an individual during socialization particularly in a family, and which influence their abilities, behaviour and responses to education at school. He sees the role of school in reproduction in the fact that school assumes an elaborated type of the language code in all children and thus hinders access to education in children with the restricted language code, which results in a cultural gap.

In the book “Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture”, Bourdieu (1990) introduces a new term “habitus” that he describes as a set of person’s characteristics developed in the process of socialisation. Children from socially more comfortable families – higher classes gain better habitus and cultural capital as they are more prepared for school, are more linguistically capable, and understand the notions significantly better. School as an institution assumes the habitus of higher classes and a greater cultural capital, and thus, children from such families are more successful in their studies and have better results than children from lower social classes. They describe school as the one that does not eliminate inequalities but the one that increases them. Studies by Katrňák (2004), Veselý & Matejů (2010), and Straková et al. (2006) support the contention that in school the common denominator are inequalities, where children from different social classes have different economic and cultural capital, which results in different attitudes to and opinions about education.

Problem Statement

We associate this status with the possibility that children whose mother tongue is Romani come from a socially disadvantaged environment that is accompanied by poverty and social exclusion. We have already mentioned that the environment children grow up in significantly influences their communication abilities. This is a very serious concern as it impacts on the equitable educational development of children whose mother tongue is Romani. This study was fuelled by this concern regarding the handicap faced by these children as they begin school.

Research Questions

The objective of the scientific project “Language Competence in Roma Pupils in First Year of School Attendance” is to identify the progress in communication skills in pupils whose mother tongue is Romani in comparison with pupils whose mother tongue is Slovak in the period of one school year (September – June). Our assumption is that there is a statistically significant difference in language maturity in terms of sentence building between pupils whose mother tongue is Romani in comparison with pupils whose mother tongue is Slovak. Hence the research question is:

Is there a is a statistically significant difference in language maturity in terms of sentence building between pupils whose mother tongue is Romani in comparison with pupils whose mother tongue is Slovak?

Purpose of the Study

Since our assumption is that there is a statistically significant difference in language maturity in sentence building between pupils whose mother tongue is Romani in comparison with pupils whose mother tongue is Slovak, the aim of the paper is to produce findings related to language maturity in pupils whose mother tongue is Romani in comparison with pupils whose mother tongue is Slovak in the first year of school attendance to either prove or disprove our assumption.

Research Methods

To obtain the data required to ascertain “Language Competence in Roma Pupils in First Year of School Attendance”, we used several research methods. The research tool, its functionality and appropriateness were verified in pre-research which was then modifies for adaptability in the field. We used the Heidelberg Speech Development Test H-S-E-T – Sentence building (SB) tool in Slovak and Romani where the pupils were asked to make meaningful sentences based on given two or three words in September and June. The results were subjected to statistical analysis which was then interpreted to present as the findings.

Sample

The research was conducted at primary schools in the Slovak Republic. The sample included pupils of the first year in the school year of 2015/2016; 69 whose mother tongue is Romani and who all came from a socially disadvantaged environment and 76 pupils whose mother tongue is Slovak. (Table

Data collection

Field research was conducted in two phases at the beginning of the school year in September and at the end of the school year in June in order to establish progress/regress.

The research ethics complied with the Act No 122/2013 Coll. on Protection of Personal Data.

Findings

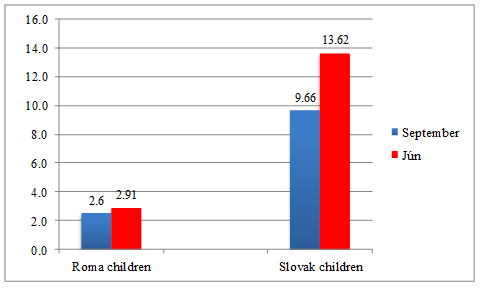

Our objective was to find out the extent of active vocabulary in children whose mother tongue is Romani and in children whose mother tongue is Slovak at the beginning of school attendance in the first year of primary school in the school year 2015/2016 in September in comparison with the second testing at the end of the school period in June.

The results in Table

Figure

Conclusion

Every human being is unique. However, the future of a child who is born and grows up in a socially disadvantaged environment is affected as the developed mother tongue can be either an advantage or a disadvantage especially when entering the common school environment along with children whose mother tongue is that of the majority (in this case, Slovak). Our findings show that children with the Romani as the mother tongue achieve significantly lower scores than children with the Slovak mother tongue in language maturity at the end of the studied period. This is probably exacerbated by the fact that these children come from a socially disadvantaged environment accompanied by poverty and social exclusion. In terms of minority languages, the environment children grow up in significantly influences their language maturity and hence their communication skills when interacting with the majority group. To some extent, our findings correspond with Bourdieu (1990) who, theorises that children from socially more stimulating environments gain better linguistic capital, are more prepared for school, are more linguistically capable, and understand the notions significantly better, and vice versa, which is also stated also by Vanková (2006), and Kaleja and Zezulková (2016). From this we can conclude that Roma children are already handicapped even as they begin school and, as our findings show, will make minimal gains and continue to trail behind the children whose mother tongue (in this case, Slovak) gives them the advantage. We can surmise that these Roma children will continue to be handicapped linguistically and socially, for the rest of their school life, supporting the theory that school, for children who come from socially and linguistically disadvantages backgrounds, will be a place that does not eliminate inequalities but the one that increases them.

The Slovak legislation defines a pupil from socially disadvantaged environment, e.g. by the Act No 245/2008 Coll. on Education: “a pupil living in an environment which, related to the social, family, economic and cultural conditions, inadequately stimulates development of mental, volitional and emotional characteristics of a child or a pupil, does not encourage his/her socialization, and does not provide enough adequate stimuli for development of his/her personality” (translated by the authors). Based on our findings, it is imperative that educational policies be developed to help children from socially and linguistically disadvantaged families studying in the school environment where the language of instruction is Slovak, so that their educational experiences are on par with the children whose mother tongue is Slovak. Children learn in conditions that nurture them; one of which is their mother tongue. If children whose mother tongue is Romani attended school with Romani as the language of instruction, these children would not fail in the educational process. Bernstein (1971) considers a language the main means of person’s socialization, and emphasizes a direct relationship between a social group and a language.

Cina and Cinová (2010) state that “the Romani language was, by the act on using the languages of national minorities that was adopted in the National Council of the Slovak Republic in 1999, declared to be an official national language. Its position was enhanced also by signing the European Charter for Regional or Minority Languages which is the most complex framework agreement regulating the issues of protection and use of the languages of national minorities in education, jurisdiction, state and public administration, media, culture, economic and social life, and cross-border cooperation, and was ratified by the Parliament of the Slovak Republic in July 2001. According to these documents, Roma can exercise their right to educate their children in their mother tongue, use Romani in official communication, or ask for bilingual signs in the municipalities with more than 20% representation of this ethnic group (according to the last Census in 2001 there were 52 such municipalities in Slovakia). The Roma themselves, however, do not exercise this act probably being unaware of the existence of such an Act, compounded by their fear to exercise their right in order not to get into conflicts with the majority. The truth is that the representatives of the majority are not prepared to accept official communication in Romani, and there are no textbooks and books in Romani in schools” (paraphrased by the authors).

At present, in Slovakia all children with the Romani mother tongue attend schools with the Slovak, Hungarian, or Ruthenian language of instruction. The hard truth is that these children need to learn to communicate in the language of the school they attend. These children have to learn in a language that is foreign to them, which is a handicap for linguistic, mental and social development. Hence, they are doomed to fail educationally and socially. We recommend the Roma parents enrol their children in kindergartens to familiarise their children with Slovak, and try to familiarise their children with Slovak in the home setting; in other words, the parents and other family members should use a bilingual mode of communication.

The Slovak Republic is a multicultural country. Many national minorities such as the Hungarians, Roma, Ruthenians, Ukrainians, Czechs, Polish, Bulgarians, Russians, Croatians, Germans, Jews, Moravians, Chinese, and Vietnamese live in our territory. The Constitution of the Slovak Republic – the highest legal document grants the right of each individual to free education at state primary schools. Primary schools, in accordance with the principles and objectives of education, should promote development of pupils’ personality on the basis of the principles of humanism, equal treatment, tolerance, democracy and patriotism, as well as development of intellectual, moral, ethical, esthetical, occupational and physical aspects. In school, by developing communication skills, pupils’ complex literacies are developed. Furthermore, primary schools should provide elementary knowledge, skills and abilities in the language, natural science, social science, art, sport, health, and traffic areas, and other knowledge and skills necessary for pupils’ orientation in life and society and their further education with the aim to increase their real chance for better future. But, the sad fact is that all this is being transmitted in Slovak, making it close to impossible for children whose mother tongue is not Slovak to develop on par with children whose mother tongue is Slovak. The findings of this study highlights that educators and policy makers in the Republic of Slovakia must be concerned about the fact that currently, primary schools are not equitable places for all children to develop. They must promote activities in the school environment which lead to success among children with whose mother tongue is not Slovak, giving such children all the opportunity to develop linguistically and socially, on par with children whose mother tongue is Slovak, so every child no matter what mother tongue they have, will develop into successful Slovakians who can contribute to this country’s social and economic development.

Acknowledgments

The paper is part of the project VEGA “Language Competence in Roma Pupils in First Year of School Attendance”; the project registration number: 1/0845/15.

References

- Bernstein, B. (1971). Class, Code and Control: Volume 1 – Theoretical Studies Towards A Sociology Of Language

- Bourdieu, P., & Passeron, J. C. (1990), Reproduction in education, society and culture, London: Sage

- Cina,S. & Cinová, E. (2010). Využitie rómskeho jazyka na 1.stupni ZŠ. Metodicko-pedagogické centrum. Bratislava

- Horváthová, J. (2002). Kapitoly z dějin Romů. Praha: Člověk v tísni, společnost pri ČT, o.p.s., 2002. ISBN 80-7106-615-X.

- Kaleja, M. A. & Zezulková, E. (2016). Školská inkluze versus exkluze: Vybrané kontexty vzdělávání sociálně vyloučených dětí a žáků s potřebou podpůrných opatření. 1. vyd. Ostrava: Ostravská univerzita, Pedagogická fakulta, 2016. 114 s. ISBN 978-80-7464-840-3.

- Katrňák, T. (2006), Faktory podmiňující vzdělanostní aspirace žáků devátých tříd základních škol v České republice” (pp. 173- 193) in Matejů, P., Straková, J. et al. (Ne)rovné šance na vzdělání: Vzdělanostní nerovnosti v České republice, Praha.

- Liégeois, J. P. (1995). Rómovia, Cigáni, Kočovníci. Bratislava: Informačné a konzultačné stredisko o Rade Európy. ISBN 80-967380-4-6.

- Lemhöfer, K., Schriefers, H., & Haniquee, I. (2010). Native language effects in learning second-language grammatical gender: A training study. Acta psychologica, 150-158. Retrieved from doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.06.001

- Mikulajová, M. (1995). Heidelberský test rečového vývinu (HSET). KL PF UK, Bratislava. 1995. Psychológia a patopsychológia dieťaťa. Roč. 30, č. 3, s. 323-325. ISSN: 0555-5574.

- Montessori, M. (1970). The Child in the Family. Virginia: Clio Press, ISBN: 1-8509-113-0.

- Portik, M. (2003). Determinanty edukácie rómskeho ţiaka. Prešov: Prešovská univerzita v Prešove, Pedagogická fakulta. ISBN 80-8068-155-4

- Pape, I. (2007). Jak pracovat s romskými žáky – Příručka pro učitele a asistenty pedagogů. Praha: Slovo.

- Rosinský, R. (2009). Interkultúrny aspekt edukácie žiakov z odlišného sociokultúrneho prostredia. In: Pedagogicko-psychologické a interkultúrne aspekty práce učiteľov žiakov z odlišného sociokultúrneho prostredia. Nitra: FSVaZ UKF, 2009 s. 129. ISBN 978-80-8094-589-3

- Říčan, P. (1991) Psychologie rodiny – obor ve stavu zrodu. In Československá psychologie, roč. 35, č. 1, s. 38-47.

- Říčan, G.K. (2003), Nová identita Českých Romu – Naděje nebo hrozba? In: V. Smékal (Ed.). podpora optimálního rozvoje osobnosti detí z prostředí minorit. Sociální, pedagogické a psychologické aspekty utváření osobnosti rómských dětí a dětí z prostředí jiných minorit. Brno: Masarykova univerzita. ČR

- Plaňava, I. (1994). Komponenty a procesy fungujíci rodiny a manželství. In Československá psychologie, roč. 38, s. 1-14

- Straková, J., & Veselý, A. (2010). “Vzdělanostní nerovnosti a jejich řešení z pohledu aktérů” (pp. 404- 420) in Matejů, P., Straková, J., Veselý, A. et al. Nerovnosti ve vzdělávání: Od měření k řešení, Praha: SLON

- Šikrová, M. (2004). Vyučovanie rómskeho jazyka na školách. In: Rómska kultúra na Slovensku v 21. Storočí, príspevky odzneli dňa 23.10.2003 na konferencii v Šamoríne. Dunajská Streda: LILIUM AURUM, s. 35 – 38. ISBN 80-8062-211-6.

- Vanková, K. (2006) Analýza sociálne znevýhodneného prostredia, jeho eliminácia a problém identity Rómov. In Rosinský R. (ed): Zvyšovanie úrovne socializácie rómskeho etnika prostredníctvom systémov vzdelávania sociálnych a misijných pracovníkov a asistentov učiteľa. Nitra: UKF, 2006. - ISBN 80-8050-987-5.

- Veselý, A., & Matejů, P. (2010). “Vzdělávací systémy a reprodukce vzdělanostních nerovností” pp. 38- 90 in Matejů, P., Straková, J., Veselý, A. et al. Nerovnosti ve vzdělávání: Od měření k řešení, Praha: SLON

- Walsh, F. (1982). Normal family processes. London: The Guild ford Press N.Y.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

14 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-052-5

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

53

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-812

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Vanková, K., Rosinský, R., & Čerešníková, M. (2019). Language Maturity In Roma Children In The First Year Of School Attendance. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2018: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 53. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 794-802). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.78