Abstract

Counterproductive work behaviour (CWB) is an important phenomenon because of its potential to affect the performance and well-being of the person engaging in CWB. CWB varied along two dimensions as directed toward organization (CWB-O) and directed toward people (CWB-P). Therefore, this study aims to analyze the link between five factor personality traits and CWB both directed toward organization and people. Emotional stability, extraversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness were hypothesized to predict CWB. To test the hypothesis, data drawn from employees in Kocaeli were analyzed via partial least squares (PLS) path modelling. Bootstrap method was used in PLS-Graph to assess the statistical significance of the path coefficients. The results revealed that emotional stability, agreeableness and conscientiousness have negative effect on CWB-O. Findings of the study show no significant relationship among openness to experience, extraversion and CWB-O. On the other hand, emotional stability, agreeableness and conscientiousness have negative effect on CWB-P. Findings of the study show no significant relationship among openness to experience, extraversion and CWB-P. According to the results of the study, one can conclude that emotional stability, conscientiousness and agreeableness are found to be important antecedents for CWB.

Keywords: Counterproductive work behaviouremotional stabilityextraversionopenness to experienceagreeableness and conscientiousness

Introduction

Although researchers describe CWB with various concepts such as delinquency (Hogan & Hogan, 1989); aggression (Baron & Neuman, 1996) deviance (Robinson & Bennett, 1995); incivility (Andersson & Pearson, 1999) mobbing/bullying (Zapf, 1996) the term generally encloses actions that workers engage in that harm their organization or organizational members. Collins & Griffin (1998) stated that in the present definitions of CWB, there is a consensus that the individuals exhibit lack of attention to explicit and implicit organizational rules, policies, and values. Another point common to the definitions of CWB is that employee intends to intentionally harm the organization. For instance, an individual who cannot do the job properly because s/he does not have the necessary knowledge and equipment should not be assessed as exhibiting CWB since the individual does not intentionally and purposefully perform poorly (Fox & Spector, 1999).

Researchers conceptualized and measured CWB in various ways. For instance, Hollinger & Clark (1983) divided CWBs into two dimensions known as property deviance (e.g. steeling company equipment and merchandise) and production deviance (e.g. taking excessive breaks, calling in sick when not). Robinson & Bennett (1995) added political deviance (e.g gossiping about employees, starting negative rumours about company) and personal aggression (e.g. endangering co-workers by reckless behaviour, stealing co-worker's possessions) to these dimensions. On the other hand, Gruys & Sackett (2003) distinguished two main property, misuse of information, misuse of time and resources, unsafe behaviour, poor attendance, poor-quality work, alcohol use, drug use, inappropriate verbal action, and inappropriate physical action.

After a while, Spector et al. (2006) has conceptualized CWB into five broad dimensions including abuse, sabotage, theft, production deviance and withdrawal. Spector et al.’s scale is widely used in empirical studies of CWB, whereas Gruys & Sackett’s have not been used by the researchers since the original paper published (Marcus, Taylor, Hastings, Sturm & Weigelt, 2013). In the scale 21 items were identified as related to CWB directed toward organization and 22 items directed toward people (clients, supervisors, colleagues). Similar to Spector and collegues (2006) Bennett & Robinson (2000) identified that CWB varied along two dimensions as directed toward organization (CWB-O) and directed toward people (CWB-P). This study measures CWB by adopting Bennett and Robinson’s scale in which CWB-O items are composed of 16 items. Some examples of CWB-O items are identified as work on a personal matter instead of work for your employer, take excessive breaks, taken property from work without permission or intentionally work slowly. CWB-P items are composed of 8 items including acts of aggression such as make an ethnic, religious, or racial remark or joke at work, spreading false rumours about others, and publicly embarrass someone at work.

Theoretical Framework and Hypotheses Development

Personality is an important determinant of individual behaviour in the workplace (Motowidlo. Borman & Schmit, 1997; Salgado 1997; Robertson & Callinan, 1998; Mount, Ilies, & Johnson, 1998; Barrick, Mount & Judge, 2001). It can affect people's perceptions and appraisal of the environment, their attributions for causes of events, their emotional responses, and their ability to inhibit aggressive and counterproductive impulses (Spector et al., 2006). Many studies have demonstrated the relationship between employees’ CWB and their individual characteristics, such as the Big-Five personality traits. Emotional stability, extroversion, openness to experience, agreeableness and conscientiousness are the main personality traits that have been investigated relating to CWB.

Emotional stability is the ability of a person to maintain a stable emotion. They are less likely to feel negative emotional states, such as anxiety, depression and anger (Costa & MacCrae, 1992; Jia, Jia, & Karasu, 2013). Emotional stability is likely to reduce the frequency of deviant behaviour such as poor work attitude, lateness, absenteeism and withholding effort (Hudson, Roberts, & Lodi-Smith, 2012; Gonzalez-Mulé, DeGeest, Kiersch & Mount, 2013). Neuroticism (lack of emotional stability), on the other hand, has been found to be the predictor of CWB (Bolton, 2010; O’Neill, Lewis & Carswell, 2011). Secondly extraversion refers to benevolence, friendliness, talkativeness and assertiveness (Antes et al., 2007; p.16). Individuals that have a high extraversion tend to be self-confident, optimistic, sociable, active and excitement seeking and are less likely to experience anger (Jensen-Campbell & Malcolm, 2006), cynicism (Lingard, 2003), emotional exhaustion (Rostami, & Mohammad, 2012) and CWB (Salgado, 2002; Berry, Ones, & Sackett, 2007; Pankaj & Patel, 2011).

Third dimension openness to experiences represents individuals’ tendencies to be creative, introspective, imaginative, resourceful, and insightful (John & Srivistava, 1999; Bono & Judge, 2004). Accordingly, a person who possesses personality traits of extraversion will be able to enjoy their work and cope with workplace challenges. Fourth dimension agreeableness refers someone who is modest, altruistic, trusting, kind and cooperative. People high in agreeableness are sensitive to the needs of subordinates and concerned about the welfare of others whereas individuals who are low in agreeableness are said to be mistrustful, sceptical, uncooperative, stubborn and rude (McCrae & Costa, 1987). Persons with low levels of agreeableness may therefore be more likely to engage in CWB. Finally, conscientiousness is among one of the most commonly studied traits in work psychology (Bono & Judge, 2004) that indicates an individual who is dependable, responsible, dutiful, self-disciplined and well organized (Costa & McCrae, 1992). Conscientious individuals experience a high degree of moral obligation; they value truth and honesty and maintain a high regard for duties and responsibilities. Conscientiousness has been found to be the strongest predictor of CWB (Salgado 2002; Chang & Smithikrai, 2010). Individuals scoring high on this dimension are more likely to avoid counterproductive behaviours since they are task oriented and goal achieving.

There are many studies such as those of Salgado (2002), Mount et al., (2006), Chang & Smithikrai (2010) that have shown the relationships between personality factors and CWB. However, little research has investigated the relationships between personality factors and CWB in Turkish context (Piskin, Ersoy-Kart, Savci & Özgür, 2013; Sezici, 2015; Gültaş & Tüzüner, 2017). Based on the literature review, this study predicts that the employees that have a high level of Emotional Stability, Extraversion, and Openness to Experience, Agreeableness and Conscientiousness are less likely to engage in activities that may harm the organization and other employees. Therefore the following hypotheses are developed.

H1: High levels of Emotional Stability will be negatively associated with CWB-O. H2: High levels of Extraversion will be negatively associated with CWB-O. H3: High levels of Openness to Experience will be negatively associated with CWB-O. H4: High levels of Agreeableness will be negatively associated with CWB-O. H6: High levels of Emotional Stability will be negatively associated with CWB-P. H7: High levels of Extraversion will be negatively associated with CWB-P. H8: High levels of Openness to Experience will be negatively associated with CWB-P. H9: High levels of Agreeableness will be negatively associated with CWB-P. H10: High levels of Conscientiousness will be negatively associated with CWB-P.

Research Method

Sample and Data Collection

Participants in this study were employees working in manufacturing industry in Kocaeli which is listed among 10 distinguished provinces where the large scale industrial enterprises located in Turkey. Tools such as e-mail, letter and face to face interviews are used for gathering data from manufacturing enterprises. A total of 144 questionnaires among 17 firms have returned. Of the 94 respondents 69% were men, and 31% were women. Furthermore, the majority of the participants hold a university degree (%46,5) and also the average age is 31 years. As regards length of service, the majority of employees (37%) have been employed for 5-10 years.

Measures

In this study all constructs were measured with already existing reliable scales. Personality Traits was measured using the Turkish version of Big Five Personality Traits Scale which has been developed by Somer, Korkmaz & Tatar, (2004) including 5 items in each dimensions. All items were measured on a five point Likert-type scale where 1= strongly disagree and 5= strongly agree. CWB was measured using 24 items adapted from Bennett & Robinson (2000). Response choices were presented in a 5-point format ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (every day).

Data Analysis and Results

PLS (partial least squares) method was used for confirmatory factor analysis. The reason for using this technique is that PLS method can operate under limited number of observations and more discrete or continuous variables. PLS is also a latent variable modelling technique that incorporates multiple dependent constructs and explicitly recognizes measurement error (Karimi, 2009; p.588). Besides ‘PLS is most appropriate when sample sizes are small, when assumptions of multivariate normality and interval scaled data cannot be made, and when the researcher is primarily concerned with prediction of the dependent variable’’ (Birkinshaw, Morrison & Hulland, 1995; pp. 646–647).

Table

Table

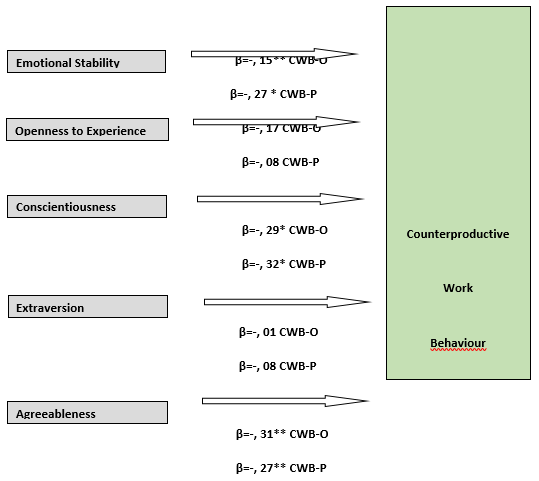

Bootstrap method was used in PLS-Graph to assess the statistical significance of the path coefficients. The results revealed that emotional stability (β=-, 15) and agreeableness (β=-, 31) and conscientiousness (β=-, 29) have negative effect on CWB-O and thus H1, H4 and H5 are supported. Findings of the study show no significant relationship among openness to experience, extraversion and CWB-O. Accordingly, hypothesis 2 and 3 are not supported. On the other hand, emotional stability (β=-, 27) and agreeableness (β=-, 27) and conscientiousness (β=-, 32) have negative effect on CWB-P and therefore H6, H9 and H10 are supported. Findings of the study show no significant relationship among openness to experience, extraversion and CWB-P. Therefore, Hypothesis 7 and 8 are not supported. According to the results of the study, one can conclude that emotional stability, conscientiousness and agreeableness are found to be important antecedents for CWB.

Conclusion and Discussions

As a result of the research implemented in order to determine the effect of five factor personality traits on CWB, it can be concluded that three of the personality traits including employee’s agreeableness, emotional stability and conscientiousness were negatively related to both CWB-O and CWB-I. This result can be anticipated since as past researches have shown that conscientiousness, emotional stability, and agreeableness are the strongest predictors of CWB (Levine & Jackson, 2002; Salgado, 2002; Mount et al., 2006; Berry et al., 2007; Sacket et. al., 2006; Bowling & Eschleman, 2010; Bolton, Becker & Barber, 2010). Conscientiousness has been found to be the strongest predictor of CWB (Chang & Smithikrai, 2010; Salgado, 2002) since conscientious individuals seems to be careful, hardworking, task oriented and goal achieving. Agreeable individuals are sensitive to the needs of subordinates and concerned about the welfare of others and this makes them less likely to engage in CWB. Finally, emotional stability is likely to reduce the frequency of deviant behaviour such as poor work attitude, lateness, absenteeism and withholding effort (Hudson et al., 2012; Gonzalez-Mulé et al., 2013).

Jensen & Patel’s (2011) argued that the level of CWB depends not only upon the person’s conscientiousness, emotional stability and agreeableness but also high levels of all three traits seem necessary. According to the results of the research individuals who were both highly agreeable and highly emotionally stable performed the lowest level of CWB while all other trait combinations were similarly higher in CWB. Thus, high levels of emotional stability do not fulfil for low levels of agreeableness, and vice versa. High levels of both traits were most strongly related to reduce CWB. Moreover, the interaction between agreeableness and conscientiousness, emotional stability and conscientiousness, agreeableness and emotional stability and also agreeableness and conscientiousness showed a similar pattern. Consequently, the authors suggest high levels of conscientiousness, agreeableness, or emotional stability are beneficial for diminished CWB only for individuals high on all of these traits.

It is important to be aware of the factors that may predict CWB that is costly to organizations and detrimental to employee’s quality of work life. Although much of the literature shows that various personality measures relate to measures of CWB, it should not be assumed that employees who engage in CWB are mentally programmed to do so. To reduce CWBs, a manager may use personality-based integrity tests and decide to give job opportunities to applicants who have appropriate traits. However, Human Resource managers may not easily preclude candidates with certain personality characteristics during the recruitment or promotional procedure since psychometrics results may not necessarily represent the outcomes of an individual in the workplace. For instance, Sackett & Devore (2001) argued personality variables (e.g., integrity, personality), job characteristics (e.g., autonomy, task identity), work group characteristics (e.g., normative deviant behaviours), organizational culture (e.g., informal security controls), injustice (e.g., perceived unfairness), and controls systems (e.g., physical security controls) are the important antecedents of CWB. In order to deepen the links between personality traits and CWBs, the complexities of interplay between individuals and the work environment should be taken into consideration.

Some limitations of this study should be mentioned. The first refers to the fact that the results were generated from a non-probability sample from employees in Kocaeli which is the fourth biggest industrial provinces of Turkey. Second, as Fox & Spector (1999) argued, self-report methodology is essentially problematical in organizational behaviour research since respondents tend to give socially desirable responses. However, to eliminate this problem the interviewer emphasized the importance of honest answers of respondents to contribute to the research. On the other hand, situational variables such as leadership style, organizational climate, job enhancement, psychological empowerment and perceived organizational justice may also influence CWB and would be useful for future research to explore. Yet, more research is needed on whether and how personality is related to CWB and also more beneficial information can be obtained from studies that include mediating and moderating variables in the study design.

References

- Andersson, L. M., & Pearson, C. M. (1999). Tit for Tat? The Spiralling Effects of Incivility in the Workplace, Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 452−471.

- Antes, A. l., Brown, R. P., Murphy, S. T., Waples, E. P., Mumford M. D., Connelly, S. & Devenport l. D. (2007). Personality and ethical decision-making in research: The Role of Perceptions of Self and Others, Personality and Ethical Decision-making, 15-34.

- Baron, R. A., & Neuman, J. H. (1996). Workplace violence and workplace aggression; Evidence on their relative frequency and potential causes. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 161-173.

- Barrick, M.R., Mount, M.K., & Judge, T.A. (2001). Personality Performance at The Beginning of The New Millennium: What Do We Know and Where Do We Go Nest, Personality and Performance, 9(1), 9-30.

- Bennet, R. J., & Robinson, S. L. (2000). Development of a measure of workplace deviance, Journal of Applied Psychology, 85, 349-360.

- Berry, C. M., Ones, D. S., & Sackett, P. R. (2007). Interpersonal deviance, organizational deviance, and their common correlates: A review and meta-analysis, The Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 410−424.

- Birkinshaw, J., Morrison, A., & Hulland, J. (1995). Structural and competitive determinants of a global integration strategy, Strategic Management Journal, 16(8), 637–655.

- Bolton, L. R., Becker, L. K., & Barber, L. K. (2010). Big Five trait predictors of differential counterproductive work behavior dimensions, Personality and Individual Differences, 49, 537-541.

- Bowling, N. A., & Eschleman, K. J. (2010). Employee personality as a moderator of the relationships between work stressors and counterproductive work behaviour, Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 91–103.

- Bono, J. E., & Judge, T. A. (2004). Personality and transformational and transactional leadership: A meta-Analysis, Journal of Applied Psychology, 89, 901–910

- Chang, K., & Smithikrai, C. (2010). Counterproductive behaviour at work: an investigation into reduction strategies, The International Journal of Human Resource Management, 21(8), 1272-1288.

- Collins, J. M., & Griffin, R. W. (1998). The Psychology of Counterproductive Job Performance. In R. W. Griffin, A. O'Leary-Kelly & J. M. Collins (Eds.), Dysfunctional Behavior in Organizations: Non-Violent Dysfunctional Behavior. Monographs in Organizational Behavior and Industrial Relations. Stamford, CT: JAI Press, 219-242.

- Costa, P. T. Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Fox, S., & Spector, P.E. (1999). A Model of Work Frustration-Aggression, Journal of Organizational Behaviour, 20, 915-931.

- Fornell, C. & Cha, J. (1994). Partial least squares, Advanced Meth Marketing Res, 52-78.

- Gültaş, İ.& Tüzüner, L. (2017). Verimlilik Karşıtı İş Davranışlarının Beş Faktör Kişilik Özellikleri ve Bilişsel Yetenek ile İlişkisi, İstanbul Üniversitesi İşletme Fakültesi Dergisi, 46(1), 47-61.

- Gruys, M. L., & Sackett, P. R. (2003). Investigating the Dimensionality of Counterproductive Work Behavior, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, (1)11, 30–42.

- Gonzalez-Mulé, E., DeGeest, D.S., Kiersch, C.E. & Mount, M.K. (2013). Gender differences in personality predictors of counterproductive behaviour, J. Manage. Psychol., 28: 333-353.

- Hogan, J., & Hogan, R. (1989). How to measure employee reliability, Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 273–279.

- Hudson, N. W., Roberts, B. W., & Lodi-Smith, J. (2012). Personality trait development and social investment in work, Journal of Research in Personality, 46, 334 –344. h

- Hollinger, R. D., & Clark, J. P. (1983). Theft by employees. Lexington, MA: Lexington Books.

- Jensen J.M. & Patel P.C. (2011). Predicting counterproductive work behavior from the interaction of personality traits, Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 466–471

- Jensen-Campbell, L., & Malcolm, K. (2006). Do personality traits associated with self-control influence adolescent interpersonal functioning?: A case for conscientiousness, Journal of Research in Personality, 41(2), 403-424.

- Jia, H., Jia, R., & Karasu, S. (2013). Cyber loafing and Personality: The Impact of the Big Five Traits and Workplace Situational Factors, Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. 20(3), 358-365

- John, O.P., & Srivastava, S. (1999). The Big Five Trait Taxonomy: History, Measurement, and Theoretical Perspectives. In L. A. Pervin & O.P.

- Karimi J. (2009). Emotional labor and psychological distress: Testing the mediatory role of work-family conflict, European J of Social Sciences, 11(4), 584-598.

- Levine, S.Z. & Jackson C.J. (2002). Aggregated personality, climate and demographic factors as predictors of departmental shrinkage, Journal of Business and Psychology, 17(2): 287 - 297.

- Lingard, H. (2003). The impact of individual and job characteristics on ‘burnout’ among civil engineers in Australia and the implications for employee turnover, Construction Management and Economics, 21, 69 –80.

- Marcus, B., Taylor, O. A., Hastings, S. E., Sturm, A., & Weigelt, O. (2013). The structure of counterproductive work behavior a review, a structural meta-analysis, and a primary study, Journal of Management, 42(1), 203-233.

- McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1987). Validation of the 5-factor model of personality across instruments and observers, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 81–90.

- Motowidlo. W. C., Borman, W. C., & Schmit, M. J. (1997). A theory of individual differences in task and contextual performance, Human Performance, 102. 71-83.

- Mount, M., Ilies, R., & Johnson, E. (2006). Relationship of personality traits and counterproductive work behaviors: The mediating effect of job satisfaction, Personnel Psychology, 59, 591-622.

- Mount, M.K., Barrick, M.R. & Stewart, G.L. (1998). FiveFactor Model of personality and performance in jobs involving interpersonal interactions, Human Performance, 11, 145-166.

- Nunnally, J.C. (1978). Psychometric theory. (2.ed.). McGraw Hill, New York,

- Pankaj M.J., & Patel, C. (2011). Predicting counterproductive work behavior from the interaction of personality traits, Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 466-471.

- O’Neill, T.A., Lewis, R.J., & Carswell, J.J. (2011). Employee personality, justice perceptions, and the prediction of workplace deviance. Personality and Individual Differences, 51, 595–600.

- Piskin M., Ersoy-Kart M., Savci İ., & Özgür G. (2013).Counterproductive work behavior in relation to personality type and cognitive distortion level in academics, European Journal of Research on Education, 2 (Special Issue 6), 212-217.

- Robertson, I.T., & Callinan, M. (1998). Personality and work behaviour, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 7, 317–336.

- Robertson, I.T. & Callinan, M. (1998). Personality and work behaviour, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 7, 321-340.

- Robinson, S. L., & Bennett, R. J. (1995). A Typology of Deviant Workplace Behaviors: A Multidimensional Scaling Study, Academy of Management Journal, 38(2), 555−572.

- Rostami, Z. & Mohammad R.A. (2012). Does academic burnout predict life satisfaction or life satisfaction is predictor of academic burnout?, Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(12), 877-895.

- Sackett, P. R., & DeVore, C. J. (2001). Counterproductive behaviors at work. In Anderson, N., Ones, D. S., Sinangil, H. K., & Viswesvaran, C. (Eds.), Handbook of Industrial, Work and Organizational Psychology (Vol. 1, pp. 145-164). London, UK: Sage.

- Sezici, E. (2015). Üretkenlik Karşiti İş Davranişlari Üzerinde Kişilik Özelliklerinin Rolü, International Journal of Economic and Administrative Studies, 7(14), 1307-9832.

- Somer, O., Korkmaz, M., & Tatar, A. (2004). Kuramdan Uygulamaya Beş Faktör Kişilik Modeli ve Beş Faktör Kişilik Envanteri (5FKE), Ege Üniversitesi Basımevi, Bornova, İzmir.

- Salgado, J.F. (1997). The Five Factor Model of personality and Job performance in the European Community, Journal of Applied Psychology, 82, 30-43.

- Salgado, J. F. (2002). The Big Five personality dimensions and counterproductive behaviours, International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 10, 117-125.

- Spector, P. E., Fox, S., Penney, L. M., Bruursema, K., Goh, A., & Kessler, S. (2006). The dimensionality of counterproductivity: Are all counterproductive behaviors created equal? Journal of Vocational Behavior, 68 (3), 446-460.

- Zapf, D., Knorz, C., & Kulla, M. (1996). On the Relationship Between Mobbing Factors, and Job Content, Social Work Environment and Health Outcomes, European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 10, 497−522.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 January 2019

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-053-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

54

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-884

Subjects

Business, Innovation, Strategic management, Leadership, Technology, Sustainability

Cite this article as:

Kaya Özbağ, G. (2019). The Role Of Personality In Counterproductive Work Behaviour. In M. Özşahin, & T. Hıdırlar (Eds.), New Challenges in Leadership and Technology Management, vol 54. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 281-289). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2019.01.02.25