Abstract

The phenomena of transsexualism is up and rising throughout the world and with the rising numbers also taking place in Malaysia, it is a phenomenon that should be dealt with head on. About one in every thousand people is affected by gender dysphoric to certain extent, they exhibit cross-gender identity, and some of them experience severe gender dysphoria since they are young, and unable to properly function in their natal gender role. In Malaysia, civil laws in the primary sense only focus on the male and female sexes when the laws are drafted. This paper will highlight the current legal standpoint in handling transsexual issues in Malaysia. Finally, the author would like to state that the production of this paper is timely as the transsexual population is fast rising in Malaysia and it is hoped that issues raised in this paper will alert the authorities to set up a task force to tackle this phenomenon.

Keywords: TranssexualismMalaysiaSocio-legal Perspective

Introduction

The term ‘transsexualism’ is believed to have emerged in the 20th century due to advancement of the medical technologies that made physical sex change possible (Hausman, 1995). According to the Oxford Dictionary, ‘transsexual’ is ‘a person who has undergone treatment in order to acquire the physical characteristics of the opposite sex’ (Oxford Dictionaries, 2017). A transsexual is a person who intends to live permanently in the social role of the opposite gender (Cohen-Kettenis and Gooren, 1999) and who desires to undergo hormones therapy and/or surgical procedures (Scutti, 2014). American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the World Health Organisation have recognised that the transsexuals are those who suffered from the gender identity disorder, which is recognised as a medical condition (Mageswary et al., 2016).

In Malaysia, transsexuals are commonly referred to as Mak Nyah, Pak Nyah, Bapok, Pondan etc. ‘Mak Nyah’, refers to the male-to-female transsexuals (Michelle, 2003) and ‘Pak Nyah’, refers to the female-to-male transsexuals. Both terminologies are Malay vernacular, which were invented in 1987 and these two terminologies are more preferable by the transsexual community (Goh, 2014).

Transsexual entities were considered as significant figures in the Malay Archipelago as in the 19th century, the Manang Bali or Iban Shamans, who were male but dressed like female, were the respectable healers and local leaders. (Goh, 2014) In the 20th century, many transwomen were appointed as royal courtiers and in 1960, the Sultan of Kelantan treated the transwomen performers with a positive manner. However, from 1970 onwards, such circumstances have diminished, mainly due to the immense expansion of Islam religion in Malaysia. In 1983, the Malaysian Conference of Rules declared a fatwa, which prohibit practice of cross-dressing and genital reconstruction surgery (“GRS”) (Teh, 1998).

In the contemporary Malaysian society, many transsexuals, especially transwomen are struggling in many aspects of their life, especially employment, education and health care (The Malay Mail Online, 2017). They encounter immense hardship to secure gainful employment and in order to survive, some of them resorted to involve in sex work. As a result, they are exposed to the high risk of HIV infection (Teh, 2008) and other sexually transmitted diseases. According to the Human Rights Watch’s report in 2017, legal criminalisation and public discrimination have caused transsexuals to avoid public health facilities and as a result, HIV prevalence among the transsexual individuals is estimated at 5.6% as compared to 0.4% among the general population. (National Human Rights Society, 2017).

Problem Statement

Although there are rising numbers of transsexuals in Malaysia, there is no proper computation of the actual population of the transsexual as it is very difficult to convince the relevant authorities that there is a significant issue on our hands to deal with. Next up, if the transsexual’s population are indeed high, then it would follow that there should be a set of regulations and laws governing this category of individuals, but to the author’s knowledge there are no specific laws in Malaysia regulating the transsexual individuals.

Research Questions

-

What are the actual population number of transsexuals in Malaysia?

-

What is the legal standpoint in the regulation of transsexuals in Malaysia, if any?

Purpose of the Study

This paper aims to analyse the current population of transsexuals in Malaysia and whether there are any laws in Malaysia to regulate this category of individuals.

Research Methods

The research that was done is library based and the study conducted was a qualitative one. The theoretical framework of this research included the relevant Malaysian statutes and regulations, cases, books, articles from journals and other reputable sources, encyclopaedias, internet sources, International Treaties and Conventions and other law-oriented materials.

Data Collection was done in the form of documents, archival records and any other socio-legal sources that were relevant to the subject matter. The data collection is library and web based. For library-based, the author referred to materials such as printed statutes and law journals or reports. For web-based, the author uses online databases such as Current Law Journal online database, Lexis Nexis online database for Malayan Law Journal etc. For each of the sources used, relevant and professional works were consulted to ensure the originality of this research.

Primary Data

The primary data was acquired through statutes, regulations and cases. The relevant statutes are Births and Deaths Registration Act 1957, National Registration Act 1959, Syariah Criminal (Negeri Sembilan) Enactment 1992, Law Reform (Marriage & Divorce) Act 1976 etc. The cases, that have been referred to were Kristie Chan v Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2013] 4 CLJ 627, Fau En Ji v Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2015] 1 CLJ 803, Corbett v Corbett [1970] 2 AER 33, Tan Pooi Yee v Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2016] MLJU 825 etc.

Secondary Data

The secondary data was derived from social journals, legal journals, press reports, reliable law and non-law websites. These secondary sources included The International Journal of Transgenderism, statistics report by the Department of Statistics and Ministry of Health, statistics reports and articles by the non-governmental organisations and news articles reported by the online news website etc.

Findings

The Transsexual Population in Malaysia

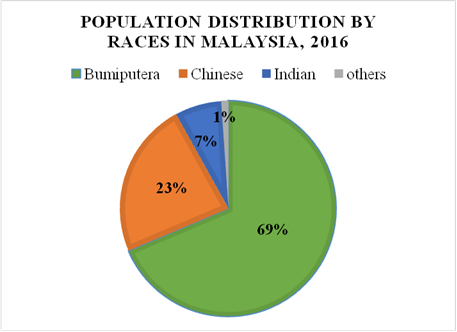

The Department of Statistics in Malaysia (“DOSM”) in 2016 reported that the estimated total population of Malaysia is 31.7 million, comprising of a male population of 16.4 million and female population of 15.3 million (Department of Statistics in Malaysia, 2016). The pie chart below shows the population distribution by races in Malaysia in the year of 2016.

Based on the pie chart above, the Bumiputera’s make up the highest population of 68.6% among the total population, followed by Chinese with 23.4%, Indian with 7.0% and others with 1.0% (Department of Statistics in Malaysia, 2016).

With regards to the population of transsexual’s in Malaysia, so far, there is no official survey conducted at the national level by the DOSM. Although there are few surveys done by certain institutions concerning the population of transsexual’s in Malaysia, in essence, the outcome from the surveys appear contradictory. Due to the contradicting population figures that have been reported and lack of official statistics on the actual population figure, the author has decided to refer to the transsexual population survey in 1990, 2001 and a transgender population survey in 2016.

In the 1990s, the Pink Triangle Foundation, which is a non-governmental organisation with main objectives being to protect vulnerable communities which include the transsexual category and to raise awareness of HIV/AID, reported that there are 10,000 ‘Mak Nyahs’ in Malaysia and among 70% - 80% of them are from the Malay ethnic, whereas the remaining 20% - 30% are from the Chinese, Indian and other races (Teh, 2001). However, the Pink Triangle’s survey focussed only on the particular ‘Mak Nyah’ group only but not the overall transsexual population in Malaysia. The above survey was further supplemented by The Malay Mail Online’s survey in 2014 which found that population of the ‘Mak Nyahs’ are much higher than the ‘Pak Nyahs’ and ‘Pak Nyahs’ “constitute a minority within a minority” in Malaysia. (Goh, 2014).

According to The Star, a privately sponsored survey was conducted in 2001 and this particular survey reported that the estimated transsexual population was at 50,000 at the material time (Farid, 2001). In 2016, Malaysian Ministry of Health reported that the estimated population of ‘transgender’ was 24,000. However, it is uncertain as to whether the term ‘transgender’ included the category of transsexuals as there are sources, which are conflicting in opinions, as to the correct meaning of ‘transgender’ (Trans Awareness Project, n.d.). The first interpretation is that, ‘transgender’ is considered as an umbrella term, which includes transsexuals (GLAAD, n.d.). Whereas the second interpretation is that, ‘transgender’ and ‘transsexual’ are two different terms, which carry different meanings, although the public at large uses both terms interchangeably (Scrutti, 2014).

If the 2016 survey is omitted due to the vagueness of the category being researched in, we can infer from the 2001 survey that there are at least 50,000 transsexuals in this country, if not more.

The Legal Standpoint in Relation to Transsexualism in Malaysia

At the outset, the author states that there is no specific legislation in Malaysia that recognises the status, rights and welfare of transsexuals in Malaysia. However, in contrast, legislations that are unfavourable to the transsexuals’ well-being are in existence. There are numerous instances of transsexuals going to court fighting for their rights and recognition, but have come to no avail. The sections below illustrate such assertions by the author.

Births and Deaths Registration Act 1957 & National Registration Act 1959

There relevant legislations, namely the Births and Deaths Registration Act 1957 (“BDRA”) and the National Registration Act 1959 (“NRA”) that have been visited on numerous instances for a direction and/or decision on the matters pertaining to transsexuals. There is no provision in the NRA authorising the National Registration Department of Malaysia (“NRD”) to alter the gender information stated on the Malaysian Identification Card or also known as ‘MyKad’. In addition, there is no provision in the BDRA permitting the recognition of altered sex of the deceased persons.

Mohd Ashraf Hafiz bin Abd Aziz, a male-to-female transsexual, had undergone a sex reassignment surgery in Thailand in 2009 and since then, named herself as Aleesha Farhana (Pandiyan, 2011). Subsequently, in 2011, Aleesha made an application to the NRD to change her name and gender stated in the identification card but the NR had rejected her application. Aleesha then sought for an order from the Kuala Terengganu High Court (Pandiyan, 2011). In the trial, the Senior Federal Counsel, who was representing the NRD, contended that there is no provision or law in Malaysia, which allows the change of gender stated on the identification card and the court, in deciding this kind of case, shall be caution as to the impact of its decision to the public interest (Jeswan, 2011). The High Court agreed to the Senior Federal Counsel’s submission and therefore, dismissed the application on the basis that the court has no power to order a gender change stated on the identification card because there is no law in Malaysia that provides for such a change (Jeswan, 2011). In addition, it is unfortunate that in the same year where Aleesha was frustrated by such ruling, she passed away due to heart complications and low blood pressure (Jeswan, 2011). Aleesha was prohibited to be buried as a female and due to Aleesha’s courageous battle of the legal recognition, her parents had encountered unnecessary ridicule and cruel taunts (Pandiyan, 2011).

In Kristie Chan v Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2013] 4 CLJ 627, the appellant, a transsexual, had undergone a gender reassignment surgery. The appellant sought a declaration to be declared as a woman and to compel the respondent, the National Registration Department (“NRD”), to change the gender information on the identification card from ‘male’ to ‘female’. Appellant revealed the difficulties in securing employment and facing immigration problems in Thailand, China and Hong Kong due to inconsistency between physical appearance and stated gender information in the registration documents.

The High Court dismissed the application with four reasons i.e. (i) as stated in the birth certificate, appellant is biologically, a male; (ii) there is no error made on the gender information that warrant a rectification under S 27 of BDRA; (iii) S 6(2) of NRA is not applicable as no error was committed on gender information of the appellant; and (iv) in Malaysia, there is no legislation governing the alteration of gender by gender reassignment surgery.

The appellant appealed against the High Court’s decision and it was dismissed by the Court of Appeal. The justifications of such dismissal, delivered by Abdul Wahab Patail JCA were, in the author’s opinion, rather unconvincing. It was held that, (i) appellant did not provide sufficient evidence to support her application. The appellant had only provided exhibits from the relevant authorities in Thailand and Hong Kong but there were no exhibits from any relevant authorities in Malaysia and no affidavits from the makers to confirm the exhibits. The alleged incident that the appellant had encountered difficulty with Thailand’s immigration had raised the question whether the gender reassignment surgery undergone by appellant was recognised by the Thailand government. (ii) There are no evidence from the medical or psychiatric experts in Malaysia to explain on what is ‘gender’, what made an individual a man or woman, and whether a sex reassignment surgery that changed an individual’s gender shall warrant a change of gender information in the identification card. (iii) The appellant had failed to discharge the burden of proof to warrant the grant of the declaration and order sought.

In Fau En Ji v Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2015] 1 CLJ 803, the applicant was biologically a female who had undergone a gender reassignment surgery at Thailand in order to transform into a male. After the surgery, the applicant applied to the respondent for change of name and gender and medical reports were submitted to support the application. Such application was rejected by the respondent. The applicant then commenced an action of judicial review against the respondent’s decision. Besides, the applicant had sought for a declaration that he is recognised legally as a male and sought a mandamus order to change his name as well as gender information from female to male.

The High Court dismissed the judicial review application by referring to the principle established in Corbett v Corbett [1970] 2 AER 33, that ‘gender’ is a complicated question to be decided, it is not determined by the applicant’s desire alone and it involves consideration of chromosomal, gonadal, genital and psychological factors. The High Court further held that, the applicant failed to comply with the ‘Kristie Chan test’ as the medical evidence provided was insufficient and it did not clarify on the chromosomal issue. Zaleha Yusof J had also cited the Paragraph 5.7 of ‘Arahan Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara’, which specifies that an application to change a sexual gender stated on an identification card is not allowed, unless, there is a court order authorising the change. Paragraph 5.7 of the ‘Arahan Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara’ or NRD Directive reads as follows:

“5.7 Penukaran Nama Kerana Menukar Jantina

5.7.1 Pindaan jantina dalam kad pengenalan adalah tidak dibenarkan kecuali atas Perintah Mahkamah.

5.7.2 Permohonan pertukaran nama kerana berlaku pertukaran jantina hendaklah mengemukakan dokumen-dokumen berikut:-

Perintah Mahkamah yang mengandungi butir-butir pengisytiharan jantina baru pemohon;

Surat pengesahan doktor Kerajaan (jika ada);

Surat pengesahan pembedahan penukaran jantina yang dikeluarkan oleh Hospital berkenaan;

Sijil Lahir (asal dan salinan).”

English translation of the Paragraph 5.7 of NRD Directive as mentioned above is as follows:

“5.7 Name Change due to Reassignment of Gender

5.7.1 Alteration of gender information in the Identification Card is prohibited except with Court Order.

5.7.2 Application for name change due to reassignment of gender shall be supported by the documents as follows:-

Court Order which contains the details of declaration of the applicant’s new gender

Endorsement Letter by the Government Doctor (if any)

Endorsement Letter for the gender reassignment surgery by Hospital in concerned;

Birth Certificate (Original and Copy)

In Tan Pooi Yee v Ketua Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2016] MLJU 825, the applicant, who was born as a female, had undergone gender reassignment surgery. Thus, the applicant sought for a declaration that “he” is legally a male and wanted to obtain consequential order to compel the Director General of NRD to change his name and gender detail in his identification card from ‘female’ to ‘male’. The application was allowed by the High Court where S Nantha Balan J was satisfied with the strong medical evidence provided by the applicant. The medical evidence, which supported the fact that, applicant is a ‘male’, are the reports submitted by the medical experts, for instance, a renowned plastic surgeon, Chartered Clinical Psychologist, Consultant Psychiatrist, Consultant Obstetrician & Gynaecologist, Radiologist etc.

S Nantha Balan J, in his judgment, had distinctively highlighted that, the area of law in Malaysia that relevant to this case and other jurisdictions are not quite settled. Judiciary’s decisions are divided as in certain cases, the courts declined to recognise the individuals who had undergone gender reassignment surgery with the justifications, inter alia, the applicants were unable to pass the ‘chromosome test’. Whereas, in JG v Pengarah Jabatan Pendaftaran Negara [2006] 1 MLJ 90, the High Court refused to apply the ‘chromosome test’ and relied heavily on the medical evidence. S Nantha Balan J criticised the ‘chromosome test’ as ‘archaic’ and shall be abolished because scientifically, it is impossible for a biological female to have male chromosomes and vice versa and hence, to insist on satisfying the ‘chromosome test’ is unreasonable.

Besides, S Nantha Balan J had also affirmed that the applicant has a right to life guarantee under Art 5(1) of the Federal Constitution as the concept of ‘life’ shall necessarily include the applicant’s right to live with dignity as a male and be legally recognised as a male. The honourable High Court judge had quoted a phrase from the book “Document of Destiny - The Constitution of the Federation of Malaysia” by Professor Dr Shad Saleem Faruqi, where:

“…the word 'life' does not refer merely to the animal existence of breathing and living. It covers the right to live with human dignity.”

However, in January 2017, the Court of Appeal decided to reverse the High Court’s decision (Melati, 2017). The Court of Appeal with three-member bench had applied the ‘chromosome test’ and held that the respondent had failed to show medical evidence on chromosome change. The Court of Appeal followed principle laid down in the English case of Corbett v Corbett [1970] 2 AER 33, where the respondent/applicant is required to provide medical evidence of the changes in chromosomal, gonadal, genitals and psychological factors (Hafiz, 2017).

S. Thilaga, an activist from Justice for Sisters, a grassroots campaign to promote Mak Nyah’s rights, stressed that the Malaysian judiciary had been applying the outdated legal precedents that are “inconsistent with science and lived experiences of trans people”. She clarified that (Koshy, 2016):

“Chromosomes do not determine our gender identity; this has been scientifically proven. Chromosomes determine our sex, which refers to our body. Gender is determined by our brain – who we are, how we see ourselves.”

Minor Offences Act 1955

Transsexual, transgender and intersex in Malaysia are vulnerable to be arrested by the police authority for ‘insulting behaviour’ under S 14 of the Minor Offences Act 1955 (“MOA”). In pursuant to S 14 of MOA, any person who speaks or behaves or exhibits in an insulting, threatening, abusive or indecent manner with intention to provoke a breach of the peace, shall be liable to a fine not more than RM 100 (Attorney General’s Chambers of Malaysia, n.d.).

States’ Islamic Criminal Enactments

In Malaysia, every state enforces Islamic criminal law. The state legislative assemblies of all the states in Malaysia are empowered by the Item 1 of List II (State List) of the Ninth Schedule to the Federal Constitution to enact Islamic criminal laws. These Islamic criminal laws have greatly affected the transsexuals in Malaysia (Shamsher, 2015).

There are numerous Islamic criminal laws enacted by the Malaysian states, for instance, S 66 of the Syariah Criminal (Negeri Sembilan) Enactment 1992 (“Negeri Sembilan Enactment”) criminalises a Muslim man who dresses in woman’s attire or poses as a woman and if convicted, the offender is liable to a fine of not more than RM 1,000 or to a jail term of not more than six months or both. S 67 of the Negeri Sembilan Enactment specifies that any person who behaves in an indecent manner in the public place shall be liable on conviction to a fine of not more than RM 500 or to a jail term of not more than six months or both. Similarly, the term ‘indecent’ is not defined under the Negeri Sembilan Enactment and hence, it infers what constitutes an indecent offence is solely judged by discretion of the relevant authority.

In State Government of Negeri Sembilan & Ors v Muhammad Juzaili Mohd Khamis & Ors [2015] 8 CLJ 975, the respondents were Muslim men, suffering from a medical condition called 'Gender Identity Disorder' (“GID”). Due to this medical condition, the respondents posed as women and expressed themselves with feminine mannerisms. They were repeatedly detained, arrested and prosecuted by the Negeri Sembilan religious authorities under S 66 of the Negeri Sembilan Enactment. As a result, this prompted the respondents to initiate judicial review to seek a declaration that S 66 of the Negeri Sembilan Enactment is void and infringed Articles 5(1), 8(1) and (2), 9(2) and 10(1)(a) of the Federal Constitution. The respondents’ action was dismissed by the High Court and the respondents subsequently appealed to the Court of Appeal. The Court of Appeal granted the application and declared S 66 of the Negeri Sembilan Enactment to be unconstitutional. However, the Federal Court overturned the Court of Appeal’s decision by a stating procedural impropriety where the High Court and Court of Appeal actually had no jurisdiction to entertain the challenge of the constitutionality of S 66 of the Negeri Sembilan Enactment.

Transsexual Marriages Not Recognised In Malaysia – Law Reform (Marriage & Divorce) Act 1976

In 2005, there was a high-profile and lavish marriage in Kuching between Joshua Beh and Jessie Chung, a male-to-female transsexual who had undergone a gender reassignment surgery (Heng, 2016). S 69(d) of Law Reform (Marriage & Divorce) Act 1976 (“LRA”) stipulates that a marriage is void if the marriage parties are not respectively male and female (Attorney General’s Chambers of Malaysia, n.d.).

Due to the LRA restriction, the couple had a customary marriage and have no intention to battle in court for the legal recognition of their marriage (Bernama News, 2005). For them, most importantly is the support and acceptance from their parents, relatives and friends. Nevertheless, Jessie Chung requested for the government to provide valid reasons for the implementation of such prohibition (Bernama News, 2005).

Conclusion

The author concludes this article by recommending that a Task Force be set up to study this phenomenon in detail to come up with suggestions and recommendations in tackling the growing transsexualism issue in Malaysia. Following calls from many quarters, the time has come for the Task Force to study on the possibility of implementing new laws for transsexuals. For Malaysia to be a truly modern, up to date globalised country, this is one way it can demonstrate to the world that by improvising the current laws in relation to transsexuals, Malaysia is moving in the right direction to be aligned with a globalised consensus pertaining to championing human rights issues on all fronts.

References

- Attorney General’s Chambers of Malaysia (n.d.). Law Reform (Marriage and Divorce) Act 1976 (Act 164). Retrieved from http://www.agc.gov.my/agcportal/uploads/files/Publications/LOM/EN/Act%20164.pdf

- Bernama News (2005, November 15). “I'm Happy with What I'm Doing”, Says Jessie Chung. Bernama News. Retrieved from http://www.bernama.com.my/bernama/v3/news.php?id=165133

- Cohen-Kettenis P.T. and Gooren L. J. G. (1999). Transsexualism: A Review of Etiology, Diagnosis and Treatment. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 46 (4). Retrieved from http://ac.els-cdn.com/S0022399998000853/1-s2.0-S0022399998000853-main.pdf?_tid=54374998-896b-11e7-9bda-00000aab0f01&acdnat=1503648152_96d3f9edee3e475f2869006e1407a196

- Department of Statistics in Malaysia (2016, July 22). Current Population Estimates, Malaysia, 2014 – 2016. Retrieved from https://www.dosm.gov.my/v1/index.php?r=column/cthemeByCat&cat=155&bul_id=OWlxdEVoYlJCS0hUZzJyRUcvZEYxZz09&menu_id=L0pheU43NWJwRWVSZklWdzQ4TlhUUT09

- Farid J. (2001, January 21). Transsexuals: Declare Us As Women. The Star. Retrieved from http://thestar.com.my/news/story.asp?file=/2001/1/21/nation/2103fbpo&sec=nation

- GLAAD (n.d.). Media Reference Guide – Transgender. Retrieved from https://www.glaad.org/reference/transgender.

- Goh J. (2014, February 16). Trans*cending tribulations: Malaysian Mak Nyahs. Retrieved from http://www.newmandala.org/transcending-tribulations-malaysian-mak-nyahs/

- Hafiz Y. (2017, January 5). NRD wins appeal not to change IC digit in transgender case. Malaysiakini. Retrieved from https://www.malaysiakini.com/news/368192#ixzz4k51d9To6

- Hausman B. L. (1995). Changing Sex: Transsexualism, Technology, and the Idea of Gender. Duke University Press. United States of America.

- Heng E. S. (2016, July 10). Speaking from her heart … Borneo Post Online. Retrieved from http://www.theborneopost.com/2016/07/10/speaking-from-her-heart/

- Jeswan, K. (2011, August 10). Transsexuals’ cry for acceptance. Free Malaysia Today. Retrieved from http://www.freemalaysiatoday.com/category/opinion/2011/08/10/transsexuals%E2%80%99-cry-for-acceptance/.

- Koshy S. (2016, August 21). She is a he – even on paper. The Star Online. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com.my/news/nation/2016/08/21/she-is-a-he-even-on-paper-posters-for-transgender-rights-often-read-some-men-are-born-in-their-bodi/#5OA2yFztUjlo4s0K.99

- Mageswary et al. (2016). Gender Recognition of Transsexuals in Malaysia: Charting the Way towards Social Inclusion. 3rd KANITA Postgraduate International Conference on Gender Studies, 16 – 17 November 2016, Universiti Sains Malaysia, Penang.

- Melati, A. J. (2017, January 5). NRD wins appeal bid to stop transgender from changing IC details. The Malay Mail Online. Retrieved from http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/nrd-wins-appeal-bid-to-stop-transgender-from-changing-ic-details#sthash.OxlKYORd.dpuf

- Michelle, L. G. (2003). Ungendering Gendered Identities? Transgenderism in Malaysia. Akademika. 63. Retrieved from http://ejournal.ukm.my/akademika/article/view/2901/1847.

- National Human Rights Society (2017, May 28). Watchdog calls for end to state laws criminalising gender, sexual identity. Retrieved from http://hakam.org.my/wp/index.php/2017/05/28/watchdog-calls-for-end-to-state-laws-criminalising-gender-sexual-identity/#more-14326.

- Oxford Dictionary (2017). Definition of transsexual in English. Retrieved from https://en.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/transsexual.

- Pandiyan, M. V. (2011). Have a heart for trans folks. The Star Online. Retrieved from http://www.thestar.com.my/opinion/letters/2011/08/04/have-a-heart-for-trans-folks/.

- Scutti, S. (2014, March 18). What Is The Difference Between Transsexual And Transgender? Medical Daily. Retrieved from http://www.medicaldaily.com/what-difference-between-transsexual-and-transgender-facebooks-new-version-its-complicated-271389.

- Shamsher S. T. (2015, May 21). How many states enforce Islamic criminal law? Malaysiakini. Retrieved from http://www.malaysiakini.com/letters/292772 .

- Teh Y. K. (1998). Understanding the Problems of Mak Nyahs (Male Transsexuals) in Malaysia. South East Asia Research, 6(2). Retrieved from http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0967828X9800600204.

- Teh Y. K. (2001). Mak Nyahs (Male Transsexuals) in Malaysia: The Influence of Culture and Religion on their Identity. The International Journal of Transgenderism, 5(3). Retrieved from https://www.atria.nl/ezines/web/IJT/97-03/numbers/symposion/ijtvo05no03_04.htm.

- Teh, Y. K. (2008). HIV-related needs for safety among male-to-female transsexuals (mak nyah) in Malaysia. Journal of Social Aspects of HIV / AIDS Research Alliance, 5(4). Retrieved from https://journals.co.za/content/m_sahara/5/4/EJC64393.

- The Malay Mail Online (2017, May 28). Watchdog calls for end to state laws criminalising gender, sexual identity. Retrieved from http://www.themalaymailonline.com/malaysia/article/watchdog-calls-for-end-to-state-laws-criminalising-gender-sexual-identity#sthash.5qCdcEO4.dpuf.

- Trans Awareness Project (n.d.). What Is The Difference Between Transgender And Transsexual? Retrieved from http://www.transawareness.org/what-is-the-difference-between-transgender-and-transsexual.html.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-051-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

52

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-949

Subjects

Company, commercial law, competition law, Islamic law

Cite this article as:

Ling, L. S. (2018). The Phenomena Of Transsexualism In Malaysia – A Socio-Legal Perspective. In A. Abdul Rahim, A. A. Rahman, H. Abdul Wahab, N. Yaacob, A. Munirah Mohamad, & A. Husna Mohd. Arshad (Eds.), Public Law Remedies In Government Procurement: Perspective From Malaysia, vol 52. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 236-246). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.03.22