Abstract

This paper examines empathy as a psychological phenomenon in the context of developing professional culture of the specialists, who learn English as a foreign language and are actively involved in intercultural communication in their professional sphere. To develop empathy as a part of professional culture, care should be taken of personal and professional development of future specialists in the process of language teaching. Such strategies as learning cross-cultural psychology through the analysis of the texts of English fiction may increase the level of students’ empathy. The research uses the descriptors for evaluating empathy development and the scaling suggested by the Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC). The paper focuses on the following research questions: What role does empathy play in professional culture of the contemporary specialist living and working in a culturally diverse society? How do university students assess their own level of empathy? Findings show that future specialists in international relations have a better awareness of empathy if the analysis of fiction as a culturally sensitive approach to foreign language teaching is used in their professional training as it gives them a better understanding of peoples’ feelings and emotions in situations of intercultural communication. It supports them in becoming more job-oriented. In the questionnaire 60 respondents of the 1st year of study from MGIMO-University (Moscow) and Ryazan State University named after S. Yesenin took part.

Keywords: Cultural diversityempathyforeign language teachinghigher educationprofessional culturetext analysis

Introduction

In recent years there has been a radical shift in the theory of professional education, which has far-reaching implications. Intercultural dimension in professional culture of the future specialist in international relations is believed to be a very important issue. The ability of the specialists in international relations to ensure a shared understanding by people of different cultural backgrounds and identities is recognized as part of professional culture. They should be able to better understand, explain, comment, interpret and negotiate various phenomena in the sphere of their professional communication.

The concept of empathy is comparatively new and it has aroused a lot of discussions about its definition. Empathy is not as simple as it seems. There is a shared sense across researchers that the meaning of empathy is not as evident as it might seem. It is a multi-dimensional construct. It has been used in different fields such as psychology, pedagogy, ethics, linguistics, and in all these fields, they have different understandings of this concept. This study explores empathy in the context of higher education. The capacity for empathy is a very important issue of the professional culture of the contemporary specialist living and working in a multicultural society.

Problem Statement

Developing professional culture by performing intercultural training through foreign language teaching to future specialists in international relations is an urgent issue. In the modern world, education is seen as a crucial factor of social development and a “soft power” tool in global competition (Voevoda, 2015a). Professional culture involves a combination of mastering the language, developing students’ personality and attitude, and cultural awareness.

The world community considers learning and teaching foreign languages as one of the values of education because linguistic diversity is definitely an essential element of cultural diversity. “The language is a socially significant form of reflecting reality and a means of acquiring new knowledge about the existing reality. Therefore, the language reflects the picture of the world inherent to a certain ethnic culture. In its turn, the language-based picture of the world is reflected in the national logics of perceiving the world, in the worldview of the nation and in the mentality of every single individual representing the ethnic community” (Voevoda, Belogurov, Kostikova, Romanenko, & Silantyeva, 2017, p. 122).

In the present paper, empathy is being investigated in the context of intercultural competence. Barrett (2018) defines intercultural competence “as the set of values, attitudes, skills, knowledge, and understanding that are needed for understanding and respecting people who are perceived to be culturally different from oneself, for interacting and communicating effectively and appropriately with such people, and for establishing positive and constructive relationships with such people” (p. 94). According to Barrett, intercultural competence consists of 14 components. All of them are included into the list of competences for democratic culture. Among the 14 components of intercultural competence, there is empathy (in particular, cognitive and affective perspective-taking skills) (ibid.).

A survey of literature on higher education in general and professional culture of specialists in international relations reveals that there is little concern with empathy. A very important document of the Council of Europe “The Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment” (Council of Europe, 2001) gives no mention of empathy. Interestingly enough, in some works empathy is confused with sympathy.

A short overview of definitions reveals that there is a great deal in common between the definitions though some of them demonstrate differences and at first sight may look even contradictory. While generally accepting empathy as a component of cultural competence, scholars differ on its nature: some refer to it in terms of attitude, others in terms of skills, some consider it a product, others a dynamic process. Evidently, they are all true in describing empathy from different perspectives and the differences between them are the result of differences in the research focus (Cultural Mediation in Language Learning and Teaching, 2004, pp. 106-107)

The term empathy has come to be widely adopted ever since, first in psychology and then in ethics, linguistics and pedagogy. Nelems (2017) explores the meaning of the commonly accepted definition of empathy as ‘the capacity to stand in another’s shoes’ and proposes that this common definition reflects a passive conception of empathy that reproduces an individualist worldview and divests empathy of its transformative and interdependent potentiality. Larocco (2017) challenges the notion that empathy is a feeling arguing instead it is orientation towards an ‘other’ that is devoid of ethical content. Chen (2013) characterizes empathy as an interpersonal phenomenon. Evidently, empathy is different from antipathy and sympathy.

Zhu (2011) writes about the significance of intercultural empathy and defines it as- “the ability of intercultural empathy is a mirror of one’s competence reflecting his understanding of the emotional states of people in the target culture, so as to minimize the psychological barriers caused by the target culture”(p.117). Barriers in intercultural empathy are stereotype, prejudice, lack of cultural sensitivity, ignorance of differences in thought patterns, ignorance of differences in values, norms and beliefs (ibid).

A recent document of the Council of Europe “Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture” (Council of Europe, 2017a) suggests to include empathy into the bulk of 20 competences for democratic culture in the section attitudes, gives descriptors for empathy and determines three levels of its development. Empathy as part of professional culture poses a theoretical and a practical challenge. It is especially interesting that it can smooth the way for a more effective, intercultural professional communication and serve as a great help in effective negotiations in cross-cultural contexts. It would be a mistake to ignore empathy in developing professional culture of the specialists in a multicultural world.

Obviously most urgent in the discussion about empathy are questions about ethics, care, relationality, altruism, social action, well-being and social change. As its core, many researchers share commitment and engaged concern that a discussion about empathy is ultimately about how we relate to, treat and are treated by others. In this research, empathy is interpreted as a skill or the capacity for carrying out complex, well-organised patterns of either professional thinking or behaviour in order to achieve a particular professional goal:

“Empathy is the set of skills required to understand and relate to other people’s thoughts, beliefs and feelings, and to see the world from other people’s perspectives. Empathy involves the ability to step outside one’s own psychological frame of reference (to decentre from one’s own perspective) and the ability to imaginatively apprehend and understand the psychological frame of reference and perspective of another person. This skill is fundamental to imagining the cultural affiliations, world views, beliefs, interests, emotions, wishes and needs of other people” (Council of Europe, 2017a, p. 48).

As for language teaching, Grineva (2014) thinks that empathy can be realized through students’ analysing and assessing the professional behaviour of literary characters and their identifying themselves with protagonists or distancing from antagonists guided by professional criteria. Beliaevskaya (2015) centers on news discourse and analytical discourse of British and American quality press to analyse new tendencies in event interpretation construal. Almazova, Eremin, & Rubtsova (2016) have developed productive linguodidactic technology as an innovative approach to the problem of foreign language training efficiency.

Despite numerous works, the problem of developing empathy as a part of professional culture of a contemporary specialist in a culturally diverse society still needs thorough investigation. In addition, further studies are required to assess students’ awareness of empathy and the way they behave in different cultural settings.

Research Questions

Research question 1: What is the role of empathy in professional culture of the future specialist in a multicultural society?

Research question 2: How do future specialists in international relations assess their own level of empathy?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to bring into prominence the issue of empathy, which is underrepresented in the theory of psychology and professional pedagogy and is underscored in the current foreign language teaching practices. The study is mainly based on observation and deals with cultural and linguistic patterns of empathy in the context of cross-cultural communication in the professional sphere at an English class. To analyze possible ways of developing university students’ empathy as a part of their professional culture we drew our attention to literature. Analyzing texts of English fiction, many students can imagine the feelings of the character, possible difficulties, feelings and emotions, and become more empathetic. It is also interesting to see if the students are aware of their own level of empathy and how they can assess it.

Research Methods

The methods used in the study are theoretical and empirical. The theoretical methods are represented by: analysis, generalization and systematization of documents of the Council of Europe and works of Russian and foreign researchers on the problem of the study. The foundation of the theoretical basis of the research consists of the works based on the ideas of foreign language teaching in the context of professional culture (Voevoda et al., 2017), on the principles of cultural diversity in knowledge dissemination (Сhernyavskaya, 2016). It is also important to mention here the issues of empathy in language learning (Grineva, 2014; Chen, 2013; Zheng, 2017; Zhu, 2011), developing empathy through the analyses of texts of the English fiction (Beliaevskaya, 2015).

The empirical methods include observation and analysis of the students’ work during English classes; systematization of the authors’ personal practical experience of foreign language teaching at University; questionnaire; comparative data analysis. A special questionnaire taking into consideration the levels of assessing empathy, suggested by “Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture” was developed to interview the students. Quantitative data were gathered through the analysis of scores of opinions received from questionnaires of 60 participants, all being first-year students, future specialists in international relations: 36 students from Moscow State Institute of International Relations (MGIMO-University) and 24 students from Ryazan State University named after S. Yesenin.

The data provide the material for comparative analysis of the students’ self and peer assessment of empathy in the context of professional culture of the future specialist in international relations. The respondents had to express their agreement or disagreement and put a tick in the necessary column, according to the key descriptors of the three levels of empathy – basic, intermediate and advanced (Council of Europe, 2017b, p. 19-20).

Findings

Research question 1: What is the role of empathy in professional culture of the future specialist in a multicultural society?

The implementation of competency-oriented approach in education and modern requirements of the labour market provide for the relevance of fostering communicative competency including its psychological features such as communication knowledge and skills. Almazova, Khalyapina, Popova (2016) consider that international youth workshops may be a way of preventing social conflicts in global developing world. In any case, language serves as a litmus test for reflecting current problems of society and communication challenges in particular (Voevoda, 2015b).

The approach we are advocating in the present study focuses on empathy as an attitude and a skill. The approach is consistent with the well-known finding that any attitudinal phenomenon requires non-attitudinal background capacities in order to function. Empathy implies learning different cultural reference systems, understanding others point of view, temporarily identifying oneself with the other, making sense of verbal and non-verbal signalling of the cultural representations (Cultural Mediation in Language Learning and Teaching, 2004).

Empathy plays a great role in developing professional culture of the future specialist in a culturally diverse society; There are several different forms of empathy that can be distinguished, but for professional culture of the contemporary specialist in a culturally diverse society most important are:

cognitive perspective-taking (the ability to apprehend and understand the perceptions, thoughts and beliefs of other people);

affective perspective-taking (the ability to apprehend and understand the emotions, feelings and needs of other people) (Council of Europe, 2017a).

Cognitive perspective-taking and affective perspective-taking skills may be realized through students’ analysing and assessing the professional behaviour of literary characters and their identifying themselves with protagonists or distancing from antagonists guided by professional criteria (Grineva, 2014).

Definitely, future specialists in international relations should be able to expresses their view about people in other countries and share their joys and sorrows. Being empathetic would be very helpful in their future work. It would increase effectiveness of their relations with colleagues from different cultures.

Research question 2: How do future specialists in international relations assess their own level of empathy?

The analysis of the students’ answers was made with special focus on the key descriptors of the three levels of empathy according to Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (Council of Europe, 2017b). The data obtained show that the respondents are very optimistic and confident valuing their capacity for empathy (Table

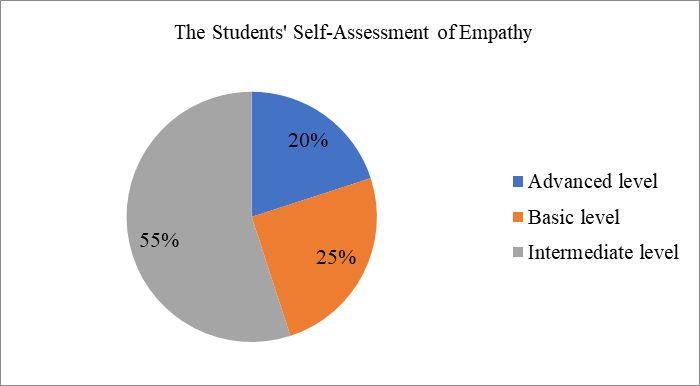

The results of the questionnaire revealed differences in students’ self-assessment. Most respondents very critically assessed their empathy judging by the key descriptors. 15 respondents (25%) out of 60 decided that their level of empathy was basic. Most respondents – 33 students (55%) – indicated an intermediate level of empathy. And only 12 respondents (20%) considered that they had an advanced level of empathy. Interestingly, only 4 respondents (7%) admitted that they could identify the feelings of others, even when they did not want to show them. It is clear that 1st-year students, future specialists in international relations have come to the university to get knowledge and professional culture and realize that they should work hard to improve their personal traits and to develop their empathy among other things. The challenges faced by teachers require the capacity for providing dialogue with students and readiness for professional creativity (Belogurov, 2016).

From the point of view of the present review, the important point to note is that educational practices and experiences that enable young people to develop empathy and to practice it within intercultural contexts are those that can be used to promote intercultural competence. By boosting students’ mastery of empathy, intercultural competence itself is boosted (Barrett, 2018).

The following diagram clearly demonstrates the correlation between the levels of competences that the students are likely to possess (Figure

To summarise, our data of the first-year students’ self-assessment of their own empathy reveal that the majority of the students – 33 respondents (55%) possess the intermediate level of empathy, 15 students (25%) – basic level and 12 students (20%) – advanced level of empathy. It means that it is necessary to pay special attention to developing empathy of future specialists in international relations as part of their professional culture.

Conclusion

To conclude our discussion of empathy, we would like to stress that it is important to recognise a meaningful role of empathy for professional culture of the specialist in a culturally diverse society. In summary, “cultural empathy is an important capacity for coping with intercultural problems adequately, effectively and satisfactorily” (Zhu, 2011, p.119).

Conceptually, the most important thing in empathy is clear understanding from a different culture’s perspective. The ways empathy works may differ within one culture and cross-culturally. Cultural and language diversity are resources for building empathy in professional communication of a specialist in a culturally diverse society. As a part of professional culture, empathy may help fulfil a number of functions: encouragement, apology, showing disapproval, comprehension check, error correction, etc. The present study showed that future specialists in international relations are aware of the importance of empathy for their future job and realize that they should work hard to develop it.

An important area for future investigation would be to find empirical evidence to prove the effectiveness of empathy as part of professional culture in different spheres of professional communication.

Foreign language teachers at universities should run classes on a high-empathy basis and should teach their students – future specialists in international relations - how to practise empathy in professional communication in order to get better results and avoid conflicts.

References

- Almazova, N. I., Eremin, Yu. V., & Rubtsova, A. V. (2016). Productive linguodidactic technology as an innovative approach to the problem of foreign language training efficiency in high school. Russian Linguistic Bulletin, 3 (7), 50-54. doi: 10.18454/RULB.7.38

- Almazova, N., Khalyapina, L., & Popova, N. (2016). International youth workshops as a way of preventing social conflicts in global developing world. In: Conference proceedings of social sciences and arts. 3rd International multidisciplinary scientific conference on social sciences and arts. Political sciences, law, finance, economics and tourism, SGEM, Vol. 1, pp. 253-260. doi: 10.5593/SGEMSOCIAL2016/HB21/S01.033

- Barrett, M. (2018). How Schools Can Promote the Intercultural Competence of Young People. European Psychologist, 23 (1), 93-104. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000308

- Beliaevskaya, E. G. (2015). Media discourse: cognitive models used to interpret events (based on British and American quality press). Issues of Cognitive Linguistics, 3 (44), 5-13.

- Belogurov, A. Yu. (2016). Strategy and methodology of teachers’ professional development during all life. Pedagogy, 7, 58–63.

- Chen, Ch. (2013). Empathy in Language Learning and Its Inspiration to the Development of Intercultural Communicative Competence. Theory and Practice in Language Studies, 3 (12), 2267-2273.

- Сhernyavskaya, V. (2016). Cultural Diversity in Knowledge Dissemination: Linguo-Cultural Approach SGEM 3rd. International Multidisciplinary Scientific Conference on Social Sciences and Arts. Conference proceedings, Vol.2, pp.443-450.

- Council of Europe (2001). Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment (CEFR), Cambridge University Press, Cambridge. Retrieved from www.coe.int/t/dg4/linguistic/source/framework_en.pdf.

- Council of Europe (2017a). Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC). Vol 1. Context, concepts and model. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/prems-008318-gbr-2508-reference-framework-of-competences-vol-1-8573-co/16807bc66c.

- Council of Europe (2017b). Reference Framework of Competences for Democratic Culture (RFCDC). Vol 2. Descriptors of competences for democratic culture. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing. Retrieved from https://rm.coe.int/prems-008418-gbr-2508-reference-framework-of-competences-vol-2-8573-co/16807bc6 6d.

- Cultural Mediation in Language Learning and Teaching (2004). G. Zarate, A. Gohard-Radenkovic, D. Lussier & H. Penz. European Center for Modern Languages. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publishing.

- Grineva, M. V. (2014). The role of empathy in developing professional identity of would-be economists in the home reading classroom. Vestnik MGIMO-University, 4 (37), 324-330.

- Larocco, S. (2017). Empathy as orientation rather than feeling: Why Empathy is ethically complex? In: Nelems, R.J., Theo, L.J. (Eds.), Exploring Empathy: its Propagations, Perimeters, and Potentialities (pp. 3-17). Leiden, Boston: Brill.

- Nelems, R. J., & Theo, L. J. (2017). Exploring Empathy: its Propagations, Perimeters, and Potentialities. Leiden, Boston: Brill.

- Simpson, E. S. C., & Weiner, J. A. (1989). The Oxford Encyclopaedic English Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Voevoda, E. V. (2015a). Сommunication barriers of the BRICS educational space. International Trends, 13 (43), 108-121. doi: 10.17994/IT.2015.13.4.43.8

- Voevoda, E. V. (2015b). Foreign language mediation activities in the dialogue of cultures. Vestnik MGIMO-University, 3 (42), 239–243.

- Voevoda, E. V., Belogurov A. Yu., Kostikova L. P., Romanenko N. M., & Silantyeva M. V. (2017). Language Policy in the Russian Empire: Legal and Constitutional Aspect. Journal of Constitutional History, 33 (1), 121–130.

- Zheng, W. (2017). Beyond cultural learning and preserving psychological well-being: Chinese international students’ constructions of intercultural adjustment from an emotion management perspective, Language and Intercultural Communication, 17:1, 9-25. doi: 10.1080/14708477.2017.1261673

- Zhu, H. (2011). From Intercultural Awareness to Intercultural Empathy, English Language Teaching, 4 (1), 116-119.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-050-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

51

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2014

Subjects

Communication studies, educational equipment,educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), science, technology

Cite this article as:

Fedotova, O., Makhmutova, E., Kostikova, L., & Gugutsidze, E. (2018). Empathy As A Part Of Professional Culture Of The Specialist. In V. Chernyavskaya, & H. Kuße (Eds.), Professional Сulture of the Specialist of the Future, vol 51. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 32-40). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.4