Abstract

In the 21st century, it is virtually impossible to find a business enterprise that would be completely independent of international relations. The globalization process has introduced interculturality to every aspect of our lives, and has brought it to our workplace. Business enterprises in Slovakia are not an exception, and feel the need to adjust not only to the technological innovations, but also to the new, diverse conditions of the global market. Our attempts in assisting enterprises to achieve in the competitive corporate environment have resulted in indulging deeply in research of intercultural competences, trying to find the best ways how assess them, and develop those that require improvement. This paper introduces an innovative assessment tool of intercultural competence, developed by our research team, and the research of intercultural competence of Slovak employees, which the tool enabled to measure. The research was conducted on a representative sample of employees of Slovak enterprises, and thus its conclusions are applicable for the Slovak corporate world. Our main objective was to assess the level of intercultural competence in order to propose further steps towards improving those competences that Slovak employees manifest lower scores in. The results have proved low level of intercultural competence, and thus create a platform for implementing intercultural training in Slovak enterprises with regard to the improvement of the overall intercultural competence of Slovak employees, as well as of the individual components: affective, behavioral, and cognitive competences.

Keywords: Assessmententerpriseinnovationintercultural competenceintercultural training

Introduction

The business world of the 21st century is almost fully globalized, and an enterprise that would not somehow cooperate with people from other cultures is hard to find. Diversity of intercultural relations is penetrating into every single aspect of human life from everyday encounters to cooperation between organizations. Contemporary business enterprises encounter interculturality very frequently, both within their business operations outside the enterprise, as well as within their working environment. Probably the most common stakeholder group which has a capacity to influence the enterprise, its focus, and possibly cultural awareness of its employees, is the customers. Along with the enterprise’s business partners, and suppliers, if from a different culture, they represent the external stakeholders that may have a great influence on how the given enterprise views and accepts diversity that has penetrated into its corporate relations. On the other hand, due to extensive migration of the labor force virtually around the whole globe, diversity has become an inevitable part of the internal corporate processes by the internal stakeholders – management and employees becoming more and more intercultural, and thus making the enterprise as a whole more diverse.

This mingling of different national cultures brings in a new need for enterprises – to become more culturally aware and flexible in meeting the needs of different stakeholder groups. Without the ability to adapt to the conditions of the new way of doing business, the efficiency of corporate processes is lagging behind those who realize the potential of intercultural education and its benefits in business environment.

Assessing intercultural competence, and finding ways to implement intercultural training into corporate processes have become efficient tools for business enterprises, as well as for different types of organizations, which enable them to use up the potential of being interculturally competent in order to succeed in the market in the fierce competition of the contemporary diverse and globalized world.

Problem Statement

Business enterprises have probably been influenced by the globalization process and multiculturality within their working processes most of all types of organizations. The technological advancements, which go hand in hand with development and innovations, have been incorporated into all spheres of existence of enterprises, and although their implementation is gradual, it was also very fast, and therefore the business world needed to adjust to new ways of operating production, providing services, and new ways of communication. One aspect of communicating across the globe, however, still appears to be rather neglected, and that is thorough focus of enterprises on their intercultural sustainability, which comprises any attempt of encouraging durable, long-lasting and resilient forms of intercultural communication and intercultural relations (Busch, 2016). As argued by Stubs and Cocklin (2008), however, sustainable intercultural relations in the workplace will not emerge by themselves but may develop as a deliberate and constant declaring of intercultural sustainability and taking active steps to support this policy by enterprises.

There are numerous factors which contribute to professional success of an enterprise. While in the past, the focus used to be on hard work ethic, examples being achievements of Nissan and Renault CEO Carlos Ghosn, or the recently retired CEO of GE Jeffrey Immelt, as an important aspect resulting in success and efficiency, the perception of what makes a successful employee, manager, or the whole enterprise, has changed greatly over the past centuries, and most significantly within the last decades. Hard work alone is insufficient to succeed in corporate environment these days, and so is high knowledge of the field if taken into account as the only deciding factor. In nowadays’ society, which carries characteristics of being immensely global, being knowledgeable about one’s industry may still not be enough, as this is not the only trait that a contemporary global employee should possess. According to Chamorro-Premuzic et al. (2017), there are three ways to identify high-potential employees:

knowledge, strategy of working with information, as well as logical and analytical thinking, which stand for the cognitive aspect of one’s working profile;

drive, attitude to work, tolerance, and empathy, which represent the motivational, affective, or emotional, aspect of one’s personality; and

social skills, adaptability to new environments, and the ability to adjust one’s action to the needs of the situations, which is the behavioral aspect brought into workplace.

This clearly suggests that to know about the subject does not alone lead to the success of the individual, or of the enterprise. As Chamorro-Premuzic et al. (2017) also suggest, even though IQ may be the single best predictor of forecasting individuals’ potential to excel or not, current employers are more interested in candidates’ social skills than their cognitive ability. Therefore, qualities of emotional intelligence, concept of which was coined by Daniel Goleman (2005), play an extremely important role and are prerequisite to success in an enterprise (Benčiková, Malá, & Minárová, 2013). Self-awareness, managing one’s emotions, and empathy are being considered as soon as during the hiring process, and continue along the work of employees, as well as managers, in the corporate environment. However, if taking account of the contemporary world’s diversity, which reflects greatly in business, it would be very short-sighted to claim that highly knowledgeable and emotionally intelligent individuals who are very successful in their own culture, will automatically be similarly good in intercultural environments. David Livermore (2011) claims that having a high IQ or emotional intelligence is simply not sufficient in multicultural business world, and through a newly established concept of cultural intelligence (CQ), he suggests a different way to approach the challenges and opportunities of the global economy. Earley and Mosakowski (2004) describe CQ as ‘an outsider’s seemingly natural ability to interpret someone’s unfamiliar and ambiguous gestures in just the way that person’s compatriots and colleagues would, even to mirror them’. According to Earley and Ang (2003), CQ stands for ‘person’s capability to adapt effectively to new cultural contexts’. Both definitions easily relate CQ to the concept of intercultural competence, which is currently greatly discussed no only among scholars, but also in media, business practice, organizational management, and by greater public.

Since most employers tend to discuss one’s competences, rather than one’s intelligence, when hiring, or evaluating the performance of their employees, it is essential to point out that cultural intelligence greatly overlaps with the concept of intercultural competence. A definition of intercultural competence (IC) given by Deardorff (2009), who understands it as ‘a set of cognitive, affective, and behavioral skills that lead to communicating effectively and appropriately with people of other cultures’, relates it to CQ concept very tightly; and so does the understanding of Womack (2009) who defines IC as the affective, cognitive, and behavioral capacity to effectively operate in an unfamiliar culture. Moreover, Piasentin (2013) argues that cultural intelligence and intercultural competence are not two different constructs, but suggests they may in fact encompass the same concept just packaged differently: CQ as a type of intelligence, and IC as a set of competences, both manifesting within the three suggested important traits of one’s personality: cognitive, affective, and behavioral. Thus, the above stated substantiates our research into assessing intercultural competences of Slovak employees, in order to help Slovak enterprises ‘to get set on the intercultural track’.

Research Questions

With regard to the previously said, intercultural competence appears to be the key competence for the contemporary business environment. Sadly, enterprises are not taking active steps towards assessing the IC level of their employees who are in direct contact with diverse cultural groups, not mention develop it through intercultural training. Among different types of courses provided for Slovak enterprises by educational institutions created for this purpose, interculturally oriented training only represents an insignificant percentage (8.7%) of the offer (Benčiková & Minárová, 2013). Therefore, our research aimed at the assessment of three components of IC among employees of Slovak enterprises in order to assist them to identify the most appropriate forms of developing them through intercultural training; that is if they show interest in it. As a direct consequence of developing the three individual ICs, we expect the enhancement of CQ levels within the respective competence areas.

We have determined several hypotheses for the research, and for the purposes of this paper, we wish to evaluate three of them. With regard to the previously conducted researches on cultural intelligence (Ang, et al., 2009; Benčiková & Malá, 2016), and intercultural competence (Kempen & Engel, 2017), the results of which showed certain trends we could base our hypotheses on, we assumed that:

H1: …the overall intercultural competence of more than a half of Slovak employees does not reach the high level.

H2: …intercultural competence increases with the level of education of Slovak employees.

H3: …the majority of Slovak employees manifest higher affective than cognitive intercultural competence.

In order to confirm our hypotheses, we used a self-assessment scale of intercultural competences that was developed by our research team and focuses on assessing the overall IC and the affective, behavioral, and cognitive ICs within the specific context of a workplace. For what competences the scale addresses, this paper refers to it as the ABC scale. It must be highlighted that the scale was developed after detailed study of the other assessment tools and their achieved results (Ang et al., 2007; Van Dyne & Ang, 2006; Kempen & Engel, 2017; Braskamp, Braskamp, & Engberg, 2014), with the concepts of the assessments covered for the most part, while the content was adjusted to serve the purposes of the working environment.

Purpose of the Study

The main objective of our study was to assess intercultural competences of employees of Slovak enterprises in order to be able to propose the most appropriate way to develop those competences that Slovak employees appear to be lagging behind in. Based on the previous studies and researches, we have established the link between IC and CQ, and may thus claim that our endeavor to develop IC in Slovak enterprises will enhance cultural intelligence of their intercultural working teams.

One of the main purposes for us to have engaged in this research was to develop such intercultural tools, which would enable the enterprises to assess the level of ICs of their employees, teams, departments, or the enterprise as a whole. The awareness of these levels on the side of the enterprise creates a platform for effective use of intercultural training (IT), which would be targeted at those ICs that an enterprise needs to develop in order to achieve competitive advantage in the international market. The IT will be tailored to specific needs of each enterprise, or its individual employees and working teams, and will be offered in appropriate forms to address all three basic ICs: the affective, behavioral, and the cognitive one.

Research Methods

Being focused on intercultural competence, IC was established to be the object of our research, while the subject was employees of Slovak enterprises of all types, sizes, and fields of industry, who are in direct contact with representatives of other cultures. The main objective of the research was to assess the levels of cognitive, affective, and behavioral intercultural competences and identify the areas that require intercultural training within the Slovak corporate world. The research was conducted on a representative sample of 657 Slovak employees, in spring 2018. 583 questionnaires, which represents 89% return ratio, were obtained from the respondents, while in order to ensure the representativeness of the sample in the selected criteria, 236 correctly filled-in questionnaires were used in the analysis of the research results.

The questioning method was used to collect the relevant data, while the questionnaire was adapted from the authors of the Self-assessment cultural intelligence questionnaire at the Michigan State University (Van Dyne & Ang, 2006), and adjusted to relate to working environment, while assessing the three independent intercultural competences: affective (A), behavioral (B), and cognitive (C), as well as the level of overall IC. The structure of the ABC scale was taken from the original questionnaire developed by American scholars, however, the method of calculating the points was improved, and the equal representation of each individual IC in the final evaluation was ensured. The structure and method of acquiring scores makes our ABC scale easy to use, and simple to evaluate. The statistical analysis and graphical interpretation of the research results have been processed by means of the statistical program IBM SPPS 19.

The ABC scale has three parts, while the first part is formed by thirty multiple-choice closed questions related to the individual ICs. Respondents were asked to choose one of the three provided answers (a, b, or c, assigned 1, 2, or 3 points), which most closely related to who they really are or how they really feel about themselves. In total, respondents could obtain a minimum of 30 points and maximum of 90, which means minimum 10 and maximum 30 for each of the three ICs. The second part of the ABC scale contains 18 questions, also related to the individual ICs, while being assessed on the Likert scale 1-4. Likert scale enables not only to obtain the corresponding response but also find out its intensity. We purposefully used an even number (4) to avoid the neutrality of the middle-value answer. In this part, respondents could achieve between 18-72 points, which means minimum of 6 and maximum of 24 for each IC. The third part of the ABC scale is composed of nine questions focusing on identification of the participating respondents.

For each of the three ICs: affective, behavioral, and cognitive, respondents could obtain minimum of 16 and maximum of 54 points. In total, as to the overall IC, respondents could obtain between 48 and 162 points. Table

Other methods which we applied in our research were the Chi-square test to determine the representativeness of the sample according to selected criteria – gender, age, and the industry field in which the enterprise operates; Spearman rank correlation coefficient test in testing the hypothesis H2, and methods of descriptive statistics and data visualization (mean, mode, median, and frequency tables) to evaluate the research results, as well as to test hypothesis H1 and H3.

Findings

The results of the research were obtained through detailed analysis of the ABC scale, which was distributed via online Google Docs application to our representative sample of respondents. We purposefully addressed those Slovak employees who worked in enterprises that have a direct contact with people from other cultures – as internal (co-workers, or management) or external (suppliers, business partners, or customers) stakeholders. As stated above, 236 correctly filled in questionnaires were used to analyze the results of our research.

Evaluation of the identification part of the ABC scale

Gender of respondents was represented in our research by 129 men and 107 women, which meets the criteria of representativeness. The structure of the sample of respondents according to age and the achieved level of education is shown in Table

With regard to the size of an enterprise, determined by the number of employees, the majority of respondents were from medium enterprises (39%), followed by large (31%), small (22%), and micro enterprises (8%). The sample of respondents was further analyzed by the characteristics of their enterprise, i.e. according to the field of industry, with most respondents working in services (55.8%), and least in agriculture (3.39%); and by the region in which the enterprise is located, with most respondents being from Central Slovakia (43.64%).

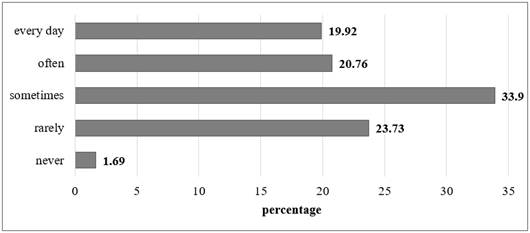

As to the position of the respondents in the enterprise from top management to a regular employee/subordinate, most (29.2%) hold the position in middle management, although our sample was represented rather equally as to this category. What was very important for us to ask was the frequency of encountering intercultural situations in the respondent’s work (Figure

From Figure, it can be deducted that an enterprise which does not have contact with other than its own culture, is represented by an insignificant percentage (1.69%), which supports the statement presented above relating to the contemporary business world being highly globalized and thus exposed to interculturality and diversity in every step of the corporate processes. As to the type of stakeholder group from other culture(s) respondents encounter most often, we found out that the most frequent encounter with other cultures is by meeting the customers of one’s enterprise (39.41%) from other cultures, followed by foreign business partners (28.81%), and co-workers (15.25%) Colleagues (1.69%) and management (5.08%) from other cultures represent a very small percentage of encountering intercultural diversity by our respondents.

The representativeness of the research sample, according to selected criteria – gender, age, and the industry field, was tested by Chi-square test, and in all three cases, was confirmed (p-valuegender = 0.966, p-valueage = 1.000, and p-valuefield = 1.000), as shown in Table

Since the sample of our research proved to be representative in all three selected criteria, the conclusions and recommendations of our research can be directed towards Slovak enterprises of all sizes and types.

Evaluation of the research part of the ABC scale

In evaluating the research part of the ABC scale, we wish to stress that different cultures may not only be represented by different nationalities. The existence of subcultures, e.g. minority cultures or ethnic groups in each country also provides great opportunity for enterprises to realize how diverse people are. Although this fact may not be very obvious at first sight, the growing internationalization of individual societies is undoubtedly a trend of the contemporary world. Therefore, the implications of the research are immense and do not only apply to strictly international enterprises.

Table

When analyzing the obtained data, it is obvious that only a very small percentage of respondents (5.5%) achieved the high level of IC. Founding our hypothesis H1 on the previous researches of cultural intelligence and intercultural competence, we noted a trend of the overall competence (intelligence) not reaching high levels. Thus by use of simple statistical methods, frequency tables and comparative analysis, hypothesis H1 may be accepted: the overall intercultural competence of more than a half of Slovak employees does not reach high level.

Data summarized in Table

Besides applying simple statistical methods in evaluating the findings of our research, we have approached the results from a more detailed analytical point of view, determined to identify potential dependence between the ICs and different variables, one of them (level of respondents’ education) being formulated in hypothesis H2 as follows: We assume that intercultural competence increases with the level of education of Slovak employees. Other variables that we tested were gender and age of respondents. To obtain reliable results, we have chosen to apply the Spearman rank correlation coefficient test. Interestingly, we found out that all ICs are independent of gender and age of respondents (p-value is higher than 0.05) although a common sense may suggest otherwise. Moderate and direct dependence, however, was proved with the achieved level of education, which means that with higher level of education, the respondent also has higher scores in the individual ICs, and thus has higher overall intercultural competence (Table

The discovered dependence between ICs and level of education substantiates our hypothesis H2, which can thus be accepted and interpreted as follows: Slovak employees who have achieved higher levels of education, e.g. university over secondary education, also achieve higher levels of intercultural competence. This finding is very significant and speaks in favor of higher education, suggesting that more training and preparation for one’s future job may in fact increase intercultural competence, which is essential in the globalized world of the 21st century.

Discussion

Our research into intercultural competence and its individual components (affective, behavioral, and cognitive), which was conducted on a representative sample of employees of Slovak enterprises in spring 2018, has revealed several interesting findings. The results of the research clearly show the direction which the development of employees’ IC may take in the near future in order to increase the efficiency of business operations of Slovak enterprises.

An interesting trend shows when our research is compared to the assessment of cultural intelligence by the Cultural intelligence scale (Ang et al., 2007; Benčiková & Malá, 2016), and intercultural competence (Braskamp, et al., 2014; Kempen & Engel, 2017). The quoted researches were based on a perception of the individual respondents related to their IC (CQ respectively). Thus, the perceived affective IC was the most developed competence in all studied samples, the behavioral IC was seen as average, and the cognitive IC was evaluated as the lowest competence of the three. Our research, however, produced different results, where the affective competence in fact proved to be at the low level for as many as 77.5% of respondents, and the cognitive competence at the middle level (53.4%). No significant differences between the researches were observed in behavioral competence. This suggests that in general, how Slovak employees perceive their level of IC does not truly correspond with the reality. Due to the fact that our research used the structure of the American self-assessment CQ scale, which is phrased in such way that rules out potential bias, and thus may be considered more objective, the reliability of the results appears to be higher in our research. Our ABC scale thus proves to be a reliable way to test one’s intercultural competence by providing an objective evaluation of the individual’s intercultural cognition, affection, and behavior.

In conclusion, Slovak employees manifest rather low scores in all ICs, as well as in the overall IC. This enables us to pose a question if enterprises sufficiently prepare their employees for intercultural encounters of the contemporary business world. Should an enterprise wish to achieve more efficiency in international market, low IC levels are insufficient, as they prove lack of cultural awareness, and thus suggest high need for improvement. Our research has proved that the competence that needs most development is the affective IC, which stands for attitudes and respect towards diversity. As the applied Spearman test has shown, the dependence between the individual ICs and the level of education has been proved, which suggests that with higher education level, Slovak employees possess higher IC. By applying Spearman, we have also proved other dependencies, the most significant being the finding that the increase in one of the ICs has a direct effect on increasing the other two, and at the same time the overall IC. These two conclusions combined enable us to propose that training any of the three ICs at the lowest educational level possible, e.g. at high school, will in fact produce higher level of the overall IC of employees in Slovak enterprises.

Conclusion

Our research has given a substantial foundation to further development of intercultural competence. We have pointed out the benefits of having highly interculturally competent employees in an enterprise, and suggested how the limitations in this matter may be reduced. Development of IC is essential, mainly with regard to today’s globalized society, where diversity of different local cultural, ethnic, generational, religious, or gender groups, and also various national cultures and subcultures is encountered virtually everywhere.

The assessment of IC within our research proved low level of overall IC, and low/middle levels of affective, behavioral, and cognitive ICs, of employees of Slovak enterprises. In none of the ICs did Slovak employees score high, which clearly leads to a conclusion that there is a great potential for IC development. This may be offered to enterprises through intercultural training provided either by outside experts and educational institutions, or by utilizing internal sources within an enterprise to promote the idea and enable tailored intercultural training with regard to the immediate needs.

As a conclusion to our research, we offer several suggestions to Slovak enterprises. Firstly, the tested ABC scale appears to be a reliable tool to assess IC within corporate environment, which discovers those areas of intercultural competence that require improvement. The scale is currently being remodeled into an innovative tool, which will be easily available to enterprises in a form of a purchasable online application and provided in the market. Secondly, in line with the results obtained from the assessment, each enterprise will be offered a specifically tailored intercultural training, aimed at those ICs which need improvement in the particular corporate environment. As our research has proved, by enhancing just one chosen IC, the other two improve as well, along with the overall IC. Therefore, the further recommendation for enterprises is to enable at least partial IT for their employees, especially in such situations where intercultural encounters are frequently experienced.

Our recommendations go even further, to education, mainly its university level, where, as apparent from the results of our research, awareness of cultural issues is extremely important due to the changes in society that the current century has brought in. By educating young people – future employees in intercultural issues, building their cultural awareness, and implanting tolerance for diversity among them, all fields of industry, individual aspects of organizational and institutional life, as well as interpersonal relations in general public will be much better off, and more competitive in facing the constantly growing interculturality in the future.

Acknowledgments

This paper is a direct outcome of the research conducted within the project VEGA 1/0934/16 – Cultural intelligence as an essential prerequisite for competitiveness of Slovakia in global environment, and is published with the projects’ support.

References

- Ang, S., Van Dyne, L., Koh, C., Ng, K.Y., Templer, K. J., Tay, C., & Chandrasekar, N.A. (2007). Cultural Intelligence: Its Measurement and Effects on Cultural Judgment and Decision Making, Cultural Adaptation and Task Performance. Management and Organization Review. 3, 335-371. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-8784.2007.00082.

- Benčiková, D., & Minárová, M. (2013). Cultural intelligences as a learning capability for corporate leadership and management. In J. Foltys (Ed.) Contemporary challenges towards management III, (pp. 11-23). Katowice: Wydawnictvo Uniwersytetu Ślaskiego.

- Benčiková, D., Malá, D., & Minárová, M. (2013). How culturally intelligent are Slovak small and medium businesses? In Loster, T., Pavelka, T. (Ed.), The 7th International Days of Statistics and Economics, (pp. 109-121). Prague: University of Economics.

- Benčiková, D., & Malá, D. (2016). Ways of Assessing Cultural Intelligence in International Organizations and the Potential of CQ Awareness for the Efficiency of Working Processes. In D. Malá, D. Benčiková (Ed.) Scientific Paper Proceedings of the VEGA Project Cultural Intelligence as an Essential Prerequisite for Competitiveness of Slovakia in Global Environment (pp. 10-20). Banská Bystrica: Belianum.

- Braskamp, L.A., Braskamp, D.C., & Engberg, M.E. (2014). Global Perspective Inventory (GPI): Its Purpose, Construction, Potential Uses, and Psychometric Characteristics. Global Perspective Institute Retrieved from: http://www.scirp.org/reference/ReferencesPapers.aspx?ReferenceID=2352906

- Busch, D. (2016). What is intercultural sustainability? A first exploration of linkages between culture and sustainability in intercultural research. Journal of sustainable development, 9, 63-76. doi:10.5539/jsd.v9n1p63

- Chamorro-Premuzic, T., Adler, S., & Kaiser R. B. (2017). What Science Says About Identifying High-Potential Employees. Harvard Business Review. Retrievedfrom https://hbr.org/2017/10/what-science-says-about-identifying-high-potential-employees

- Deardorff, D. K. (2009). The Sage Handbook of Intercultural Competence. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications.

- Earley, C., & Ang, S. (2003). Cultural Intelligence: Individual Interactions Across Cultures. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Earley, C., & Mosakowski, E. (2004). Cultural Intelligence. Harvard Business Review, 10, 1-19.

- Goleman, D. (2005). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More than IQ. New York: Bantam Books.

- Kempen, R. & Engel, A. (2017) Measuring intercultural competence: development of a German short scale. Online-Zeitschrift für interkulturelle Studien, 16 (2017) 29, 39-60. doi: Anghttps://nbn-resolving.org/ urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-55722-7

- Livermore, D. (2011). The cultural intelligence Difference Special E-book Edition: Master the One Skill You Can’t Do Without in Today’s Global Economy. NY: AMACOM Div American Mgmt Assn.

- Piasentin, K. A. (2013). Assessing cross-cultural competence: Implications for selection and training in the Canadian forces. Technical report DRDC TR 2012-067. Retrieved from cradpdf.drdc-rddc.gc.ca/PDFS/unc140/p538194_A1b.pdf

- Stubs, W., & Cocklin, C. (2008). Teaching sustainability to business students: Shifting mindsets. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 9, 206-22. doi: 10.1108/14676370810885844

- Van Dyne L., & Ang, S. (2006). A Self-assessment of CQ. Retrieved from http://www.linnvandyne.com/papers/Van%20Dyne%20CV%20%20Oct%201%20%202015.pdf

- Womack, S. (2009). Cross-Cultural Competence Assessment Instruments for the U.S. Military Academy’s Semester Abroad Program. (Dissertation). Retrieved from: http://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/353

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-050-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

51

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2014

Subjects

Communication studies, educational equipment,educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), science, technology

Cite this article as:

Bencikova, D., Mala, D., & Minarova, M. (2018). Equipping Enterprises With An Intercultural Competence Assessment Tool. In V. Chernyavskaya, & H. Kuße (Eds.), Professional Сulture of the Specialist of the Future, vol 51. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 212-223). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.24