Abstract

This article is devoted to the issue of professional plurilingual training at university. The findings of the research work are of both theoretical and practical value to foreign language training at non-linguistic university in artificial learning environments. In the introductory part of the article the key differences between polylingual education and multilingual education are stated; the emergence of the term “plurilingual” is highlighted. First, distinctive features of plurilingual training are discussed; second, the reason for plurilingual training being advantageous at university is explained; third, basic principles of plurilingual training are presented. On the basis of literature analysis on the topic of multilingual and polylingual training some principles were selected and borrowed for plurilingual training. Preliminary findings provided by experimental teaching are included to demonstrate feasibility of some principles. A survey was carried out to demonstrate public interest in plurilingual training at non-linguistic departments and to study students’ attitude to language learning itself. The main principles that determine professional plurilingual training are represented. Each principle is viewed in terms of what it means, how it can be implemented in practice and why this principle is considered to be essential for professional plurilingual training at university level. Generally, the findings can be used to arrange professional plurilingual training in groups of students whose major is not connected with linguistics. The findings will also be used to conduct a further pedagogical experiment.

Keywords: Homogeneous skillsintegrationinterferencelearning principleslearning strategiesplurilingual training

Introduction

Before dealing with the principles of professional plurilingual training, it is essential to explain what the term “professional plurilingual training” means. The term “plurilingual training” itself is still a rare term to be found in works on modern linguodidactics. It is derived from the newly-coined term “plurilingual education”, which is based on the concept of plurilingualism. This concept of “plurilingualism” is analysed in detail in the article “From multilingualism to plurilingualism” by Ch. Tremblay and belongs to the field of language policy. According to Tremblay (2007), one should distinguish the terms “multilingualism” and “plurilingualism”. This differentiation caused demarcation of the terms “multilingual education” and “plurilingual education” in language teaching in Europe.

In Russian (and in post-Soviet countries) linguadidactics there are two terms, which describe the field of multiple language learning and teaching, “polylingual” and “multilingual” education. Consequently, it is obvious that the emergence of the third term describing the same field of studies causes certain confusion. Having analyzed and compared works on the three types of education, we came up with the following distinctive features (see Table

On the basis of this comparative analysis we assume plurilingual education in this particular sense as the most relevant one to meet the needs of the modern society which is currently undergoing the process of full-scale integration. However, under no circumstances do we reject the studies carried out in the field of multilingual education and polylingual education. On the contrary, we emphasize their importance and their contribution to the emergence and further development of plurilingual education. “Plurilingual education” is seen as a term that happened to be on the crest of the paradigm shift wave (Bernaus, 2004; Kun, 2015; Styopin, 2016; Dupuis et al., 2004).

When a paradigm shift occurs in science it entails reexamination and reconsideration of already established terminology that characterizes the old paradigm as well as the emergence of new terms belonging to the new paradigm. Therefore, in our study we make an attempt to converge the European term “plurilingual training” and those findings of Russian and post-soviet countries methodology (principles) which stand along with the former.

We use the term “professional plurilingual training” to mean language training (Rus. “obuchenie”) in at least two foreign languages in a group of students whose major subject is other than linguistics; English as the first foreign language is related to the professional field of students; the second foreign language is studied in a framework of a general language course of A1 level.

Problem Statement

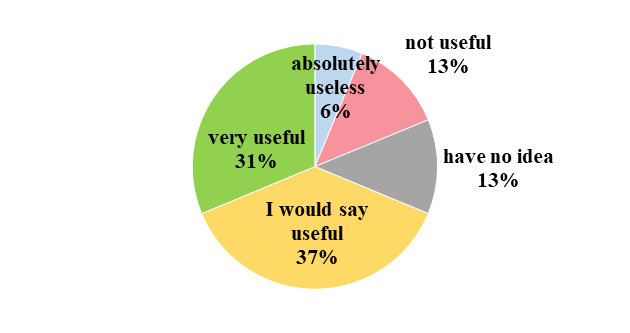

It is widely considered that the idea of studying at least two foreign languages at university is not going to be productive and fruitful in a group of students whose major is other than linguistics. There are a number of reasons that support this idea: few hours for language teaching in a curriculum, lack of interest among students, the process of studying English is time- and effort- consuming itself, etc. However, many students and alumni face the necessity of learning/using other foreign languages in their life while dealing with business trips, conferences, etc (see Figure

Research Questions

In order to find out the principles of professional plurilingual training, we had to answer the following research questions: what the principles of multilingual and polylingual training are; how these principles are implemented; how these principles correlate with plurilingual paradigm; what people expect from a language class at university; whether people know how to learn a foreign language.

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to mark out certain principles that would make professional plurilingual training at university possible. In the frame of the research we deal only with students of Russian universities who study foreign languages in artificial learning environment (without native speakers).

Research Methods

In the research we employed the following methods: literature analysis on the topic of multilingual, plurilingual and polylingual education as well as on the topic of foreign language acquisition; an observational method and a survey method.

The observation carried out is characterised with a high degree of locality (as opposed to quantitative research methods). The primary reason for that is that we set as one of the objectives of the research to explore student individual learning trajectory, the way a student acquires a certain topic or grammar rule, the speed of transforming knowledge into a skill; another objective was to see which language skills can be considered homogeneous and had better be studied separately in time; another objective was to test the elaborated exercises and activities for the future pedagogical experiment. Students have been having individual classes in General English via Skype in small groups since January, 2018. They are studying for B1 level now. They started from A1 level (almost from the beginning) and the planned final stage is B1 level (Intermediate level). Each group has classes twice a week (26 weeks have passed so far at the moment of the submission of the article and that constitutes 52 lessons). Each class lasts for 60 minutes. This experimental teaching cannot be considered as a completely developed course but serves as a basis for testing the materials for the future pedagogical experiment.

The survey was carried out to explore how people (alumni and students) see the way a language should be taught at university; their attitude to the introduction of the second foreign language in the curriculum; the way people imagine language learning process and the way they learn a foreign language. The target audience for the survey is represented by alumni and students of non-linguistic departments at different universities. The survey was carried out with the help of the Google Forms platform. 98 respondents have taken part in the survey so far.

Findings

We live in the age when novelty comes from skillfully produced integration of well selected already existing criteria that are usually slightly corrected after some reconsideration in accordance with the given conditions. The emergence of plurilingual education illustrates this idea perfectly well. The due theoretical analysis and experimental data analysis being accomplished, the following principles that should determine professional plurilingual training at university were marked out and are represented below. These principles are borrowed from different areas of language acquisition theory and practice and are modified or adapted by us to the framework of professional plurilingual training at university.

Generally, each paragraph describes one principle and encompasses three dimensions: what the principle means; why this principle is essential for the stated kind of plurilingual training; and how it can be implemented in language teaching at university.

Integration principle

Integration principle being one of the fundamental principles of modern education is borrowed from works on polylingual education, “multilingvodidaktika” and CLIL (Barushnikov, 2004; Coyle, 2008; Mosienko & Hazhgalieva, 2016; Merino & Lasagabaster, 2018; Meyer, Coyle, & Halbach, 2015; Pavon, 2018; Coral, Lleixa, & Ventura, 2018; Ramos & Pavón, 2015). Here integration stands for integration of cultural and linguistic information, integration of language and content (CLIL), and integration of two foreign languages in a curriculum. The first type of integration is quite clear and does not need any specification, whereas the second and the third ones need an in-depth explanation.

Integration of language and content, that is largely pursued by those who do research in CLIL (Coyle, 2008; Meyer, Coyle, & Halbach, 2015; Coyle, Hood, & Marsh, 2010), in our case only slightly reminds CLIL and has little to do with CLIL technologies. In CLIL content learning is prioritized over language learning, and language learning is considered to be done automatically through reading and working with the content. Thus, Khalyapina analyzing the similarities and differences between CLIL and ESP (English for Specific Purposes) says, that CLIL characterizes educational situations when disciplines or their sections are conducted in a foreign language, realizing a bilateral orientation: studying of a discipline by students and studying of a foreign language (Khalyapina, Almazova, & Popova, 2017). According to Marsh (Coyle, Hood & Marsh, 2010), CLIL means "the subject and language integrated training" which belongs to any educational context focused on two objects. At the same time a nonbasic language of students in which the course is conducted is used as means of teaching the discipline. According to Coyle and Meyer (Coyle, Halbach, Meyer, & Schuck, 2018; Meyer, Coyle, & Halbach, 2015) within this methodical approach a substantial component – content is a backbone. They underline the importance of defining a subject of development, the purpose, a task as a set of theoretical knowledge and skills which allow students to realize and formulate right professional opinions, statements within the problems discussed while studying. At the same time language training of the student is guided by "gaining" of a lexical and grammatical component, but their role is on the second position. In the first position stands the professionally oriented discourse. In other words, CLIL is specified first of all by a changing role of the foreign language. In CLIL approach this role is concentrated on the idea of being a medium for accepting and understanding professionally oriented discourse, professionally oriented problems on the level of their conceptualization, on understanding the specifications of future professional issues.

In our case we first focus on thorough grammar and vocabulary learning and only after we show how this language can be “integrated” with content. It means that a student first gets acquainted with certain grammatical and lexical constructions, learns how to employ them properly in speech, and after he/she goes on to practice the constructions through facing the content. This technology is also different from ESP approach, as the students first familiarize themselves with the content (a text), which is afterwards followed by exercises on grammar and vocabulary (Almazova, Baranova, & Khalyapina, 2017). We consider the sequence “grammar and vocabulary exercises + content” to be more effective in terms of language learning in class, as this sequence allows to work straight with the content without wasting time on acquiring new words and grammar while reading. Thus, more speaking and content-related activities can be done in class. In practice a lesson becomes equal to one unit which consists mainly of two parts: in the first part new grammar and vocabulary are introduced and trained; and in the second part a text is studied and discussed.

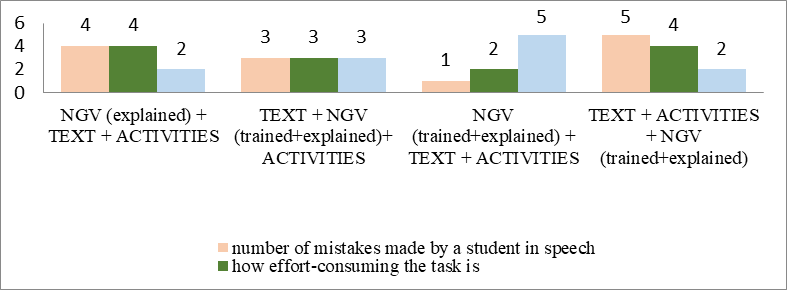

As was observed during the experimental teaching, among four selected sequences the sequence “grammar and vocabulary exercises (NGV) + text + speaking activities” demonstrated better results in terms of the following criteria: the number of mistakes in speaking activities, how effort-consuming each speaking content-related activity is fora student, the involvement of students in working with the content. Each criterion is evaluated in the range from 1 to 5 points by a teacher. On the basis of this preliminary teaching experiment we can assume that students generally demonstrate greater willingness in working with content in particular with content-related speaking activities when they are already skilled enough at pronouncing and employing the vocabulary and grammar used in the text (see Figure

Integration of two foreign languages is implemented through integration of English language for specific purposes course, e.g. English for physicists, and general course on other foreign language at elementary level, e.g. Spanish or French. The demand for the second foreign language in a curriculum has been proved by results of the survey (see Figure

Assigning one language to one lesson contributes to better code-switching. Two languages should not be practiced within one lesson under any circumstances, especially when a student does not demonstrate stable language skills in either of the languages. However, the accidental usage of two foreign languages within one lesson when it is appropriate (to illustrate the differences or similarities between the languages, for example) is welcomed. Furthermore, code-switching can be trained in a passive way through perceiving some information in both languages on a daily basis (e.g. by using VK posters).

Basic learning strategies

This principle anticipates the autonomous learning principle (Timirbaeva, 2007) borrowed from works on polylingual education. We slightly modify the principle and make it focus on developing basic learning strategies rather than other more complex learning strategies. Every student is supposed to be able to use basic strategies to learn a language. These basic strategies include memorizing new words and grammar constructions; working with vocabulary independently; ability to be aware of personal language acquisition process (individual learning trajectory) and ability to evaluate personal progress.

The experimental teaching has showed that students, although they might know how to work with vocabulary and new grammar at home on their own, do not do it on a regular basis (lack of discipline, laziness, low motivation, etc.) and often fail to evaluate their progress correctly. Mostly they tend to think that they learned the rule once and that they do not need to revise it later. As a consequence, they fail to convert the rule into a skill and gradually the learned material fades away from their memory and their speech.

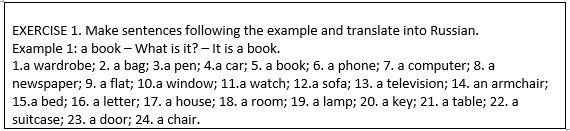

In practice this principle implies performing simple activities aimed at memorizing new vocabulary or grammar constructions in class. These activities should be simple enough to be reproduced independently by students at home and must be practiced with the teacher at every lesson. For example, each list of new words (nouns) can be first introduced by doing the exercise in Figure

Thorough language learning procedure principle

Generally, a language course represents a certain procedure that is determined by the sequence of units, where each unit can be subdivided into smaller parts. According to the principle, the transition from one part to the next part of the unit (and the same thing is true for a course) can be done only if the first part was thoroughly studied and is evaluated by a teacher and a student as a well-developed set of skills. This principle is borrowed from “multilingvodidaktika” by Baryshnikov (2004) and is also followed by Listvin (2015).

We consider this principle obligatory for professional plurilingual training. However, we see it necessary to complement the principle by accepting the constant and continuous revision of already studied parts. This revision should be done using the 2-d row type exercises (see 6.6. Articulation speech activity principle). The experimental teaching showed that even though the grammar and vocabulary material was studied thoroughly enough and students demonstrated quite stable skills in using it in speech, these skills tend to deteriorate with time if not continuously practiced. The 2-d row type exercises, from our point of view, better fit for such revision because students are meant to extract from their memory all the studied words and grammar; whereas, the 3-d row type exercises allow more flexibility and contribute more to developing compensatory competence rather than revising the studied material.

Effortless learning effect principle

The process of learning a language should be perceived as a clear and simple process that requires minimum efforts and seems manageable for every student. This goal is achieved through thoroughly elaborated exercises and activities and also through the limited number of vocabulary and grammar constructions selected. It would allow creating that feeling of relatively effortless learning. We include this principle into the basic set of principles, as in the course of experimental teaching we saw students who lack some language skills lose interest to studying the language and participating in the activities. Thus every activity should be simple enough for each student.

Homogeneous skills reduced interference principle

This principle is borrowed by us from German language manuals by Listvin (2015) and is extended to plurilingual training. This principle aims at reducing interference when developing homogeneous skills inside one subsystem (inside one language). For example, in Spanish language you have to separate “estar” and “ser” in the curriculum, as they represent similar skills that can be easily confused. While conducting experimental teaching, we observed students facing certain difficulties in their attempts to acquire simultaneously the following topics: adjectives ending with –ED and –ING; the verb “to be” in present simple and other verbs that need the auxiliary verbs “do” and “does”; present simple passive and the construction “have smth done”, etc. All these topics have to be separated in the curriculum. Otherwise when studied simultaneously or within several lessons in a row students tend to confuse the constructions further in practice. Although we borrow this principle from Listvin (2015), we extend the principle to the field of plurilingual training and report that second foreign language should be introduced only when student demonstrate relatively stable skills in first foreign language.

Articulation speech activity principle

We borrow this principle from Listvin´s language teaching practice as well (Listvin, 2015) and modify it by introducing 3 rows of activities. This principle is based on a rule that about 90% of time in class students should “speak” the language they learn. However, this principle should not be confused with commonly accepted speaking activities, such as projects and cases where students have to speak on their own discussing some issues, or to express their opinions in an extensive manner (although such activities can also be performed in class). This principle involves replacing written grammar exercises with specially elaborated oral exercises that should be done in class. These exercises should be quite simple and are usually done in turns by each student. The example of such an exercise is represented in Figure

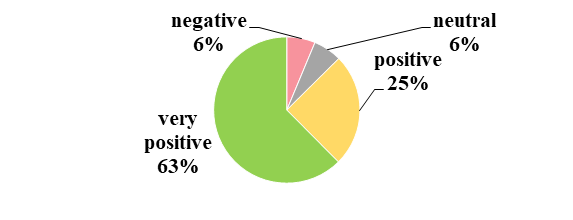

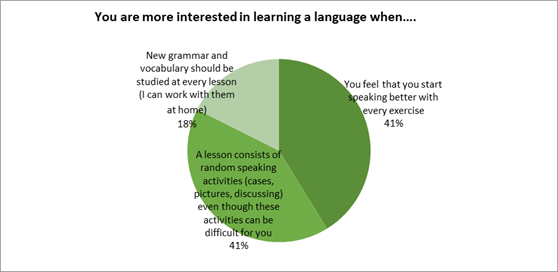

Between fully speaking activities (when a student is supposed to be able to express his/her ideas on his own) and the1-st row exercises there is still a gap that has to be fulfilled. Consequently, we suggest introducing the 2-d row type exercises that imply extending the 1-st row exercises to pair work activities. These pair work activities involve asking questions, requesting and providing information to and from each other in a group of two people. The distinctive feature of the 2-d row type exercises is that they contain a limited number of language constructions that can be used in the conversation between the students. This number is determined by the task and provided worksheets. The survey showed that students prefer to have more speaking activities (cases, games, etc) in class (see Figure

The 3-d row exercises are basically speaking activities within the chosen topic. Such exercises imply students´ independent answers (e.g., cases, projects, open questions, etc.). These activities can be employed to work with the content-related material.

Conclusion

To sum it up, on the basis of literature analysis, an experimental teaching and a survey conducted we conclude that professional plurilingual education can be implemented if these principles are followed. Now we are elaborating teaching materials based on the principles for conducting a pedagogical experiment. The findings can be useful for those who do research in the field of multiple language learning.

References

- Almazova, N.I., Baranova, T.A., & Khalyapina, L.P. (2017). Pedagogical approaches and models of integrated foreign languages and professional disciplines teaching in foreign and Russian linguodidactics. Yazyk i kul'tur, 39, 116-134. doi:10.17223/19996195/39/8.

- Baryshnikov, N. V (2004). Mul'tilingvodidaktika . Inostrannye yazyki v shkole, 5, 19–27. [in Rus.]

- Bernaus, M. (2004). Un nuevo paradigma en la didáctica de las lenguas [A new paradigm in language didactics]. Glosas Didacticas, 11, 3-13. [In Spanish]

- Coral J., Lleixà T., & Ventura C. (2018). Foreign language competence and content and language integrated learning in multilingual schools in Catalonia: an ex post facto study analysing the results of state key competences testing. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(2), 139-150. doi: 10.1080/13670050.2016.1143445

- Coyle, D., Halbach, A., Meyer, O., & Schuck, K. (2018). Knowledge ecology for conceptual growth: teachers as active agents in developing a pluriliteracies approach to teaching for learning (PTL). International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(3), 349-365. doi:10.1080/13670050.2017.1387516

- Coyle, D., Hood, Ph., & Marsh, D., (2010). CLIL: content and language integrated learning. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, UK: New York

- Coyle, D. (2008). CLIL - a pedagogical approach from the European perspective. Encyclopedia of Language and Education, 4, 97-112.

- Khalyapina, L.P., Almazova, N.I., & Popova, N.V. (2017). Models of interdisciplinary coordination in higher education area of Russia. In Gómez Chova, A. López Martínez, I. Candel Torres (Eds), 10th International Conference Of Education, Research And Innovation, Iceri Proceedings 2017 Conference (pp. 780-785). Seville: IATED Academy. doi: 10.21125/iceri.2017.0287.

- Kun, T.S. (2015). Struktura nauchnyh revolyucij [The Structure of Scientific Revolutions]. Moskva: AST. [in Rus.]

- Listvin, D. (2015). Full course. German language. Moskva: AST. ISBN: 978-5-17-089835-0. [in Rus.]

- Merino, J., & Lasagabaster, D. (2018). CLIL as a way to multilingualism. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 21(1), 79-92. doi:10.1080/13670050.2015.1128386

- Meyer, O., Coyle, D., & Halbach A. (2015). A pluriliteracies approach to content and language integrated learning - mapping learner progressions in knowledge construction and meaning-making. Language culture and curriculum, 28, 1, 41-57. doi:10.1080/07908318.2014.1000924

- Mosienko, L. V., & Hazhgalieva G. H. (2016). Cennostnye osnovaniya samoopredeleniya studentov v polilingval'nom obrazovanii [Values in self-identity of students in polylingual education]. Vestnik Orenburgskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta, 2(190), 39-45. [in Rus.]

- Pavon, V. V. (2018). Learning Outcomes in CLIL Programmes: a Comparison of Results between Urban and Rural Environments. Porta Linguarum, 29, 9-28.

- Ramos, M. C., & Pavón, V. (2015). Developing cooperative learning through tasks in Content and Language Integrated. Remie-Multidisciplinary Journal Of Educational Research, 5, 2, 136-166.

- Styopin, V.S. (2016). Istoriko-nauchnye rekonstrukcii: plyuralizm i kumulyativnaya preemstvennost' v razvitii nauchnogo znaniya [Historical and scientific reconstructions: pluralism and cultural succession in scientific knowledge development]. Voprosy filosofii, 6, 5-14. [in Rus.]

- Timirbaeva, G. R. (2007). Polylingualism as a principle in Professional Communication and Translation Studies in polylingual community. Vestnik Kazanskogo tekhnologicheskogo universiteta, 3-4, 268-272. [in Rus.]

- Dupuis, V., Heyworth, F., Leban, K., Szesztay, M., Tinsley, T., & Berke, S. (2004). Facing the future: Language educators across Europe. Strasbourg: Council of Europe Publ.

- Tremblay, Ch. (2007, November 7). Du multilinguisme au plurilinguisme [From multilingualism to plurilingualism]. Retrieved from https://www.observatoireplurilinguisme.eu/fr/ [in Fr.].

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 December 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-050-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

51

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-2014

Subjects

Communication studies, educational equipment,educational technology, computer-aided learning (CAL), science, technology

Cite this article as:

Khalyapina, L. P., & Shostak, E. V. (2018). Principles Of Professional Plurilingual Training. In V. Chernyavskaya, & H. Kuße (Eds.), Professional Сulture of the Specialist of the Future, vol 51. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 970-979). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.12.02.105