Abstract

School violence is a big phenomenon nowadays, with social and educational implications. This issue has increased the concern of educational and health professionals, encouraging the development of intervention programs. The aim of this study is to identify the existence of bullying practices in children attending elementary school and characterize the influence of a set of socio-demographic variables underlying these behaviors, such as their family and school contexts. 201 children were studied, mostly males (53.73%), with a mean age of 9.60 years and enrolled in the 4th year of elementary education, in rural and urban schools of the central region of Portugal. Two survey instruments "Bullying: The Aggressiveness among Children in School Space" and the "Natural Child Environment Signaling Scale", validated for the Portuguese population, were used to gather the data necessary for the study. The findings suggests that 26.90% of children are involved in bullying behaviors with verbal and physical aggression highlighted as the most common type. The school playground was revealed as the favorite places for these practices (91.30%). Bullying behaviors were shown to be significantly influenced by family environment (p <0.001), and not significantly, by gender, age, number of non-approvals, attendance in kindergarten and number of siblings. These results show that certain strategies need to be considered in the planning and implementation preventive bullying where educators, teachers and psychologists can intervene to improve the mental and physical health of children.

Keywords: Childrenbullyingviolenceschoolfamily environment

Introduction

Characterized by physical and/or physiological violence, in an intended and continuous way, by an individual or a group of people against other individual(s), or group (s), without any apparent reason (Olweus, 2010), bullying is a hot topic in social media these days and it occurs in almost every school (Smith, Kwak, & Toda, 2016). Bullying can be characterized using three criteria that, according to Olweus (2010) and Carvalhosa (2017), assimilates:

Focusing on the persons that initiates in the bullying practices and their characteristics, we may state that the

Children who are victims of bullying normally present as immediate consequences, a heightened nervous tension, with symptoms like headaches and gastralia, and they may also experience nightmares or panic attacks. In some cases, a shift in behavior can occur, like tantrums and negativity, phobia or school fear that frequently results in a hard time concentrating in chores or even in absenteeism or escape from school. After the aggressions, children may feel sick or indisposed, and experience little group acceptance; they are not chosen as best friends and present very limited social abilities in the execution of group tasks, cooperation, sharing or mutual support (Carvalhosa, 2017; Rigby, 2010). Olweus (2010) contends that there are situations where the victimization prologues itself, and the late bullying effects may lead to a clinical state of neuroses, hysteria and depression; this being more frequent in girls than boys.

Bullies show, as an immediate consequence, a hard time maintaining friendships, although they are positively accepted by their peers even in the face of aggressive behaviors. They are unhappy at school; with below average results and low appreciation by their teachers (Carvalhosa, 2017). Bullies also have difficulties in controlling impulses and anger, easily entering conflicts with their colleagues and with adults; therefore, presenting a deficit in social skills and irrational beliefs, as they believe they will not suffer any consequences following their aggressions resulting in a belief that violence is the only means to an end (Matos, Negreiros, Simões, & Gaspar, 2009; Smith, Kwak, & Toda, 2016). Bullies may become later, as a delayed consequence, offenders and in that context to stand trial by crimes, because they have a hard time respecting the law and integrating into society. They may even become easily involved with risky behaviors concerning their health, like alcohol, cigarettes and drugs consumption (Carvalhosa, 2017; Olweus, 2010).

Problem Statement

School violence is a worrying phenomenon nowadays, with great implications at an educational, familial and social level. These days, we are often alerted by situations of violence that occur between children in Portuguese schools. The reason that this is a current topic may emerge from the well-founded fact of the negative consequences in the emotional, psychic and mental development of the children involved resulting from these behaviors. In this context, urgent intervention is required from adults, parents and specifically teachers, because they are the ones who spend the most time with the children. Hence, they are required to have an extensive and structured knowledge of the children’s their qualities and defects. It is also important to emphasize the importance of the role of the family to eliminate bullying. The children, on their own, may not acquire defense strategies. The role of the family is crucial as adults can help handle bullying behaviors in a way that helps to minimize the children’s suffering in the school environment. Even though bullying is not a new phenomenon, at the moment it is of great concern and interest for the students themselves, their parents, school, health and media professionals. The investigations in this area will ultimately lead to the production of knowledge which would facilitate the creation of formative and educational intervention programs that approach these behaviors in the school and familial environment. Hence, it is obvious that an investigation focusing on bullying practices among children is timely and relevant, as it would allow for a better understanding of the associated factors, which will prospectively enable the implementation of educational strategies in younger school-age children, with the purpose of attenuating these practices.

Starting with this delineation of the problem, we decided to lead a study that helps identify the existence of bullying practices in a group of Portuguese children who attend elementary school, with the purpose of promoting an intervention based on data-driven knowledge and not just an ineffective buildup of strategies and procedures. We wish to highlight that children at this school level were selected for this study due to the few available studies done with children within this age range. Those available, and there are many done in Portugal about bullying, are directed to populations with a greater age range.

Research Question

Taking into account the contextualization of the subject of study, and assuming the importance of scientific evidence as ground for a preventive intervention (consequent and effective) on bullying behaviors in school and familial backgrounds, our concern is expressed in the following question:

How are socio-demographic, familial and school variations associated with bullying practices in children attending Portuguese elementary school?

Purpose of the Study

With this question in mind, and the increasing awareness spread by the Portuguese media about the consequences and negative effects these behaviors may have on the physical and mental health of the children involved, which motivated us to conduct this investigation, we point out that the present study pursues three general purposes: the

Research Methods

This investigation is based on a quantitative transversal study following the precepts of a non-experimental study, also known as “ex post facto” study, or correlational and observational study. Bullying practices were considered the dependent variable and the independent variables were the socio-demographic background of the aggressors and victims such as their gender, age, place of residence and the attended school, familial background such as their parents’ level of education, occupation, the type of family and familial environment the child experiences in terms of the presence or absence of violence, as well as the number of siblings, and if the child has older or younger siblings. School background such as school areas where aggression behaviors occur more commonly, the rates of failure and kindergarten attendance. In the present study, bullying practices were acknowledged when three or more aggressions (both as assaulted and as aggressor) were verified simultaneously.

Participants

The selection of the study participants was based on probability sampling by conglomerates (the population individuals constituted natural groups: schools and academic years). More specifically, we proceeded to do a random selection of eight public elementary schools from the districts of Leiria and Coimbra, four in each area (urban vs rural). A raffle of the classrooms (not the children individually), i.e. the evaluated classrooms were randomly chosen from all the existent classrooms in the selected schools was conducted in each of these educational establishments.

The inclusion criteria for the sample was the individual’s age range, which had to be between 8 and 12 years; and the absence of educational specials needs. Once the selection process was completed, the group under study was formed (Table

Measuring instruments

The gathering of the data integrated 3 sections: the first part (Section A) included 13 questions about the social-demographic and family contexts of the children; for the second part (section B) the survey “Bullying and Aggressiveness Among Children in School Space”, validated for the Portuguese population (Pereira, B., 2008) was used; and in the Section C the “Natural Child Environment Signaling Scale - SANI” was used, assembled and validated by Sani (2003). The scale incorporated in section B aims to evaluate a whole set of dimensions underlying the practice of bullying in school, consisting of 28 items, distributed by four factors: factor I on friendship, consisting of 2 items that seek to know if the child has friends or is usually alone; factor II, on victimization, which consists of 13 items related to the frequency of victimization, types of aggression, locations and who attacks; factor III, on aggression, which includes 7 items related to aggression, whether the child attacks, round trip to school and the number of students in his or her room who attack; and, lastly, factor IV on recreation, consisting of 6 items that seek to know if children enjoy the playground, if they have room to play and what they think of it. The scale SANI comprises 30 items aimed at identifying, from the children’s point of view and using as reference their familial environment, situations of physical, psychological and emotion abuse, taking 4 factors into consideration, whose Cronbach alpha values varies between .73 and .86. The four factors are: first -

Methods

The methodology used for the data collection (that occurred in June 2017) was identical in every school included in this study, being previously authorized by parents and legal guardians of the children who signed the informed consent, and by an ethical committee who approved the execution of the study in each school. The statistical data was processed by computer, using the program

Findings

Table

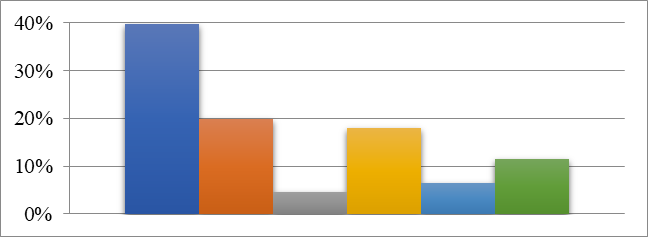

Taking into consideration the type of aggression, and given the variety of answers, these were gathered into four types of aggression: physical aggression (this one includes the answers “they beat me, punched me and kicked me”, “they shoved me and threw things at me”, among others), verbal aggression (which integrates responses like “they called me bad names”, “They told things about me or my body”, “They spoke of me behind my back, telling my secrets”, and similar statements), social aggression (referring to responses like “they didn’t talk to me”, and others) and psychological aggression (which includes responses like “they scared me” and others). By studying the given answers, showed in figure

Next, we evaluate a set of variables associated with the aggressor’s profile such as: the number of aggressions committed, their gender and age (table

In terms of the global prevalence of bullying practices, the results in table

In relation to the reports of the children, and using as reference the occurrence of some conflicting events (observed or experienced in the familial environment, measured by the

Contextualizing the results from the association study between bullying practices and some of its causes, the variables gender (p=0.977), age range (p=0.828), number of siblings (p=0.673), the existence of younger or older siblings (p=0.067), number of school year repeats (p=0.998) and attendance of kindergarten (p=0.148) did not show a statistically significant effect associated with bullying practices. On the other hand, the association study between bullying practices and the familial environment of the children proved, by the Pearson correlations expressed in table

Conclusion

Taking into consideration the aims of this investigation, the obtained results allows us to conclude that: (1) About 26.90% of children were involved in bullying practices, as an aggressor or as a victim; (2) Physical aggression was the most reported type of aggression (19.90%), followed by verbal aggression (17.91%); (3) Most children reported the aggression to their parents (33.98%) but not to their teachers (30.35%); (4) when faced with aggression, most teachers intervene only occasionally (22.98%) or often (most times) in the aggression management (22.39%); (5) Bullying practices are not significantly affected either by gender (p=0.977) or age (p=0.828) of the children involved; (6) it is irrelevant whether children have repeated school years (p=0.822), or attended kindergarten (p=0.148) as these factors do not show any significant differences in the incidence of bullying; (7) There is no significant difference in the existence of bullying practices regarding children with siblings (p=0.673) and if they have or not older or younger siblings (p=0.067); (8) On the other hand, there is a very significant relationship between bullying practices and familial environments where violence occurs.

With this empiric framework in mind, we can conclude that a transversal and multidisciplinary awareness is imperative by the most several educative agents toward their students, because we believe it is fundamental to create an educational system supportive of citizenship education. In another context, the obtained results highlight some important orientations to take into account in the planning and implementation of preventive strategies of this phenomenon that needs to be implemented for the good of the children and their families.

Therefore, we need to assume the need for an increasing involvement,

In summary, this study has highlighted some orientations that need to be considered in the planning and implementation of preventive strategies of this phenomenon, where educators, teachers and psychologists may play a significant role by providing effective intervention with the children and their families, and thus, encourage a higher degree of physical and mental health.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our gratitude to the schools that participated in the data collection for this research. We also acknowledge the financing for this study by FCT (MaiSAÚDE MENTAL Project/Reference: CENTRO-01-0145-FEDER-023293) and CI&DETS/Polytechnic Institute of Viseu.

References

- Azenha, M., Rodrigues, S., Galvão, D. (2012). Bullying e a criança com doença crónica. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, III Série, 6, 47-55.

- Canavarro, M.C. & Pereira, A.I.F. (2007). A avaliação dos estilos parentais educativos na perspectiva dos pais: A versão portuguesa do EMBU-P. Psicologia: Teoria, investigação e prática, 2, 271-286.

- Carvalhosa, S. (2017). Prevenção da Violência e do Bullying em Contexto Escolar. Lisboa: Climepsi Editores.

- Matos, M., Negreiros, J., Simões, C., Gaspar, T. (2009). Violência, Bullying e Delinquência – Gestão de Problemas de saúde em meio escolar. Lisboa: Coisas de Ler Edições

- Olweus, D. (2010). Bullying in school: Evaluation and dissemination of the Olweus Bullying Prevention Program. American Journal of Orthopsychiarty, 8(1), 124-134.

- Pereira, B. (2008). Para uma escola sem violência – estudo e prevenção das práticas agressivas entre crianças (2nd ed.). Lisboa: Dinalivro.

- Rigby. K. (2010). Bullying interventions in Scholls: Six basic approaches. Australia: Acer Press.

- Sani, A. (2003). Escala de Sinalização do Ambiente Natural Infantil (SANI). In L.S. Almeida, M.R. Simões, C. Machado & M. Gonçalves (Eds.). Avaliação Psicológica: Instrumentos validados para a população portuguesa, (Vol.III, 89-98) Coimbra: Quarteto Editora.

- Smith, P., Kwak, K., & Toda, Y. (2016). School bullying in different cultures: Eastern and western perspectives. Cambridge: University Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

19 November 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-047-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

48

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-286

Subjects

Health, psychology, health psychology, health systems, health services, social issues, teenager, children's health, teenager health

Cite this article as:

Albuquerque, C., Rodrigues, C., Andrade, A., Campos, S., Cunha, M., & Bica, I. (2018). School Bullies And Bullying Behaviors. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, R. X. Thambusamy, & C. Albuquerque (Eds.), Health and Health Psychology - icH&Hpsy 2018, vol 48. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 277-286). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.11.30