Abstract

ICT transform traditional social-cultural practices and create new opportunities for maintaining old and finding new social ties, using social contacts to ensure the success of the individual's activities. To study this changes we consider some aspects of social capital online, such as communication platforms, the size of social network, bridging and bonding, the strength of social ties and convertibility of social capital into others resources. Based on generational theory, we use data from Russian population study of 1554 adolescents 12-17 years old, 736 youth 17-30 years old and 1105 parents of adolescents differentiating generations «X», «Y» and «Z». To measure various aspects of social capital, we use a number of questions with the choice of the answers. By the results of the study the social capital on the Internet is most actively accumulated by the generation «Y». The social capital of generation «Z» shows stable growth dynamics online, adolescents quickly and easily reach the average values of the Dunbar’s number (150), reflecting the limits and opportunities for social contacts for the average adult. At the same time, the adults themselves, generation «X», are the poorest in terms of social contacts. Internet also transforms representation of bonding (absence of parents and relatives in friend list) and bridging (presence of subscribers and «unfamiliar friends») social capital online of generation «Z». The social capital of generations «Y» and «Z» is characterized by high convertibility online. Generation «X» feels more constrained in using the opportunities of online space to manage its social capital.

Keywords: Social capital onlinesocial tiesgeneration theoryadolescentsRussian population study

Introduction

Infocommunication technologies transform traditional social-cultural practices, including practices of social interaction and communication. Communication becomes one of the most common activities on the Internet along with the search for information. The Internet creates new opportunities for maintaining old and finding new social ties, using social contacts to ensure the success of the individual's activities. In this connection, the question becomes what is the social capital online and how its accumulation and use arise.

Social capital is a broad and debatable concept that arose on the border between economics and sociology and is actively used in various scientific fields, including in psychology. The definitions of social capital can be conditionally divided into three types based on the chosen focus (Adler & Kwon, 2002): 1) on orientation to external relations, that also has been called «bridging», for example, «the sum of the resources, actual or virtual, that accrue to an individual or a group by virtue of possessing a durable network of more or less institutionalized relationships of mutual acquaintance and recognition» (Bourdieu & Wacquant, 1992), or «friends, colleagues, and more general contacts through whom you receive opportunities to use your financial and human capital» (Burt, 1992, p. 9) on orientation to internal relations, that is, the relationship between the participants within the group, that also has been called «bonding», for example, «features of social organization such as networks, norms, and social trust that facilitate coordination and cooperation for mutual benefit» (Putnam, 1995), or «Social capital is defined by its function. It is not a single entity, but a variety of different entities having two characteristics in common: they all consist of some aspect of social structure, and they facilitate certain actions of individuals who are within the structure» (Coleman, 1990, p. 302) on both types of linkages, for example, «the sum of the actual and potential resources embedded within, available through, and derived from the network of relationships possessed by an individual or social unit. Social capital thus comprises both the network and the assets that may be mobilized through that network» (Nahapiet & Ghoshal, 1998). Similar classification can be created on the basis of other criteria, for example, the characteristics of social ties (strong or weak links, horizontal or vertical, open or closed, etc.). Nevertheless, the general elements of different definitions of social capital are resources and relationships whether on a micro, meso or macro level.

Despite the controversy and complexity of the definition, social capital is very popular in science by its interdisciplinarity and explanatory potential, that allows comprehensive research and analysis of complex social processes (Soldatova & Nestik, 2010). Studies of social capital are gradually expanding into online contexts. Nevertheless, the accumulation of knowledge about the features of social capital functioning on the Internet is at an initial level.

Problem Statement

There are opposite opinions about the influence of the Internet on the formation of social capital. Thus, arguments are given in favor of the insulating nature of the Internet and its negative impact on the growth of social capital (Putnam, 2000; Nie et al., 2002; Gershuny, 2003; Wellman et al., 2001). This is largely due to the fact that the arguments were expressed in works created shortly before the extension of online networks and did not differentiate recreational and social online activities. On the other hand, there are studies on the positive contribution of the Internet, especially social networks, to the strengthening and development of social capital in various areas: strengthening of bridging и bonding social capital, increasing social activity and self-esteem of children and adolescents, as well as socialization and well-being of the elderly, coping with social anxiety and loneliness, maintaining of weak or latent links that might otherwise disappear, the growth of civic engagement and participation in the political life of the society, the enhancement of social trust and promotion of collective action (Sabatini & Sarracino, 2014; Neves et al., 2018). Nevertheless, the features of social capital online require further detailed analysis for a more comprehensive understanding of the problem.

In our study, we consider some aspects of social capital online, such as communication platforms, the size of social network, bridging and bonding (Putnam, 2000), the strength of social ties (Granovetter, 1983) and convertibility of social capital into others resources (Bourdieu, 1985) such as opportunities for support from others. All these aspects will also be considered in the context of intergenerational comparison, depending on the specifics of Internet development by different generations. So, the social capital of «digital immigrants», who mastered the Internet in adulthood, and «digital aborigines», who knew the online world from childhood, can vary significantly. Based on the generational theory of N. Howe and W. Strauss (1991, 1993), in studies, modern adolescents are increasingly referred to as the generation «Z», significantly different from the older generations – «Y» (youth) and «X» (adults). It is «Z» and «Y» that belong to the digital generation, whose socialization, to some extent, has been taking place in the context of the increasing integration of digital technologies into everyday life. They are actively developing the Internet, which, we expect, leads to a more rapid increase in social capital online. Thus, we can assume that the features of its accumulation and use will be different for representatives of different generations.

Research Questions

The article is devoted to a comparative study of the phenomenon of social capital online in representatives of the generations «Z», «Y» and «X».

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to identify the peculiarity of social capital in adolescents, youth and adults online.

Research Methods

The study used the primary data obtained in 2017-2018 in 17 cities from 8 Federal regions of Russian Federation.

Samples.

In accordance with N. Howe, W. Strauss (1991, 1993) generation theory and with adaptation to the cultural and social context of Russia and of Internet development in Russia (Soldatova & Rasskazova, 2016), the samples included representatives of three generations: 1029 adolescents 14-17 years old (52 % female) and 525 adolescents 12-13 years old (54 % female) – generation «Z», 736 youth 17-30 years old (59 % female) – generation «Y» и 1105 parents of adolescents 12-17 years old (80.6 % female) – generation «X».

Methods.

To measure various aspects of social capital, we have used a number of questions with the choice of the answers. The space of social communications was measured by the question «What social networks or resources do you use?». To measure the size of social network and bonding/bridging social capital we prepared the questions: «How many friends do you have on the social network?», «Approximately how many friends do you personally communicate with on the social network during the last 6 months?», «How many people from friends do you know in real life?», «How many subscribers do you have on the social network?», «Who from the list below is in your friends: 1. Parents, 2. Brothers and sisters, 3. Grandparents, 4. Uncle and aunts, 5. Teachers, 6. Parents of friends, 7. No one» (for young people, answer 6 was replaced by «Employers and colleagues»). The last two questions were asked only for adolescents and young people.

Convertibility of social capital into others resources was measured by the question «What is the approximate number of friends you might ask to spend a few hours to help you do something in offline or online?». These questions relate to the most frequently used social network.

Findings

Relying on empirical studies, we try to identify differences in the features of social capital online in representatives of three generations.

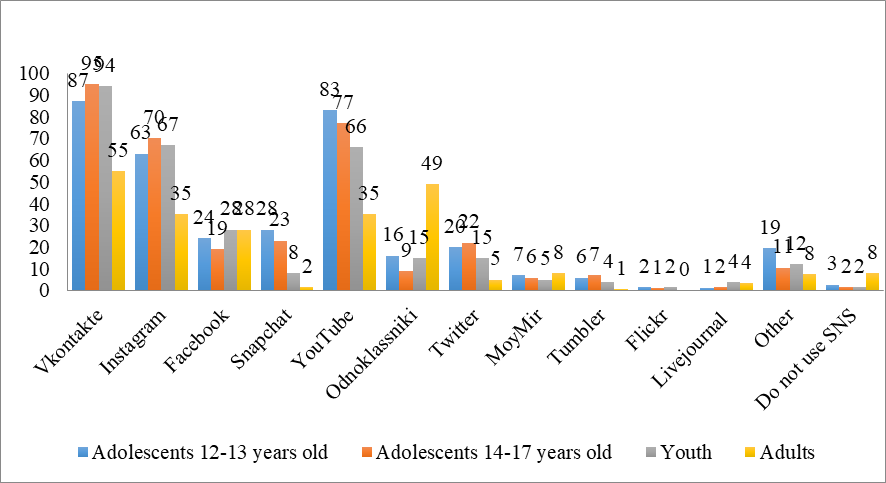

6.1. First of all, we can talk about the differences in the spaces for the formation of social capital online (Figure

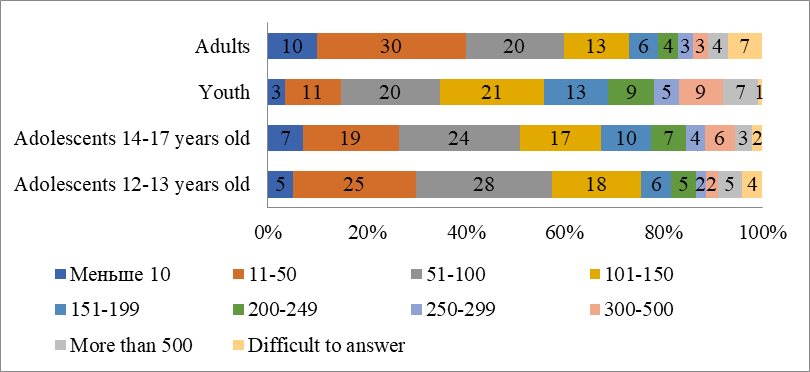

6.2. The size of social network differs among representatives of different generations (Figure

6.3. The amount of friends only partially characterizes the social capital of a person. It is important to understand the nature of social ties. We found out with how many friends the respondent personally communicates in the social network within six months. A narrow circle of online communication (less than 10 people) is typical for 47% of adults, 37% of youth, 32% of elder and 34% of younger adolescents. Up to 50 people are present in online communication 31 % of parents, 44% of young people, 40% of younger and 46% of elder adolescents. Each eight adolescents communicates in SNS with 50-100 people, and each seven – with more than 100 people. In order to understand the bonding social capital online, it is also important to analyse strong social ties and find out which of the important adults and relatives is in the online social community of the generations «Z» and «Y». Every sixth adolescents did not have any of significant adults and relatives in his friend list. In the younger age group, half of the respondents have parents, the elder adolescents and young people have lower indicators (42 % and 43% respectively). Most often from the family circle «in friends» there are brothers and sisters (61-77%). Uncle and aunt are also in friends (28-34%). At the part of adolescents "in friends" there are also parents of friends (22-30%). More than a third of the respondents include their teachers in the list of friends (39-45%). Every second among young people transfers a circle of professional contacts to the online space (58%).

6.4. Weak ties as a resource of bridging social capital were considered in the specific online context of the subscribers amount and unfamiliar offline friends. Every fifth adolescent has an insignificant amount of subscribers - less than 10 people. Up to 50 subscribers have 29% of younger adolescents, 16% of elder adolescents and 14 % of youth. 1/6 of respondents have from 50 to 100 subscribers, in this case adolescents have already caught up with the youth. From 100 to 300 subscribers from every third representative of generation «Y» (32%), but elder adolescents practically do not lag behind youth (29%). 300-500 subscribers appeared in the lists of 7% of young people, 6% of elder and 4% of younger adolescents. At the same time, more than 500 subscribers have been added to a relatively large number of users: 10% for young people, 9% for elder and 7% for younger adolescents. We also present the results of the analysis of weak ties on the basis of «strangers» in the list of friends. According to the results of the study, the more friends there are, the more «strangers» are allowed into virtual life. At the same time, generation «Z» do this more often than «Y». Among 50-100 friends adolescents do not know the fifth part from the contact list, from 100-200 friends - more than a quarter, and from more than 200 friends - already third. Those many teenagers have "unfamiliar friends" on social networks. Young people in this sense are more often personally acquainted with friends in SNS - from 200 friends – a fifth part of «strangers», from more than 200 friends – a quarter.

Conclusion

Тhe new possibilities of digital technologies have changed the ways of accumulating and managing social capital. The obtained research results demonstrate the features of social capital among the generations.

Acknowledgments

This work is supported by the Russian Science Foundation, grant № 18-18-00365.

References

- Adler, P. S, Kwon, S.-W. 2002. Social Capital: Prospects For a New Concept. Academy of Management. The Academy of Management Review, 27, 17-40.

- Bourdieu, P. (1985). Social Space and the Genesis of Groups. Theory and Society, 14, 723-744.

- Bourdieu, P., &. Wacquant, L. P. D. (1992). An Invitation to Reflexive sociology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Burt, R. (1992). Structural Holes: The Social Structure of Competition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Gershuny, J. (2003). Web-use and net-nerds: A neo-functionalist analysis of the impact of information technology in the home. Social Forces, 82(1), 141-168.

- Granovetter, M. (1983). The Strength of Weak Ties: A Network Theory Revised. Sociological Theory, 3, 201–233.

- Howe N., & Strauss W. (1991). Generations: The history of America's future, 1584 to 2069. N.Y.: William Morrow & Company.

- Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (1993). 13th Generation: Abort, Retry, Ignore, Fail? New York: Vintage Books.

- Nahapiet, J., & Sumantra, G. (1998). Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Academy of Management Review, 23(2), 242-266.

- Neves, B., Fonseca, JRS, Amaro F, Pasqualotti A (2018) Social capital and Internet use in an age-comparative perspective with a focus on later life. PLoS ONE, 13(2), e0192119. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0192119

- Nie, N. H., Sunshine, H. D., & Erbring, L. (2002). Internet Use, Interpersonal Relations and Sociability: A Time Diary Study. In Wellman, B., & Haythornthwaite, C. (Eds). The Internet in Everyday Life (pp. 215-243). Oxford: Blackwell.

- Putnam, R. (2000). Bowling Alone: the Collapse and Revival of American Community. New York.

- Putnam, R. D. (1995). Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy, 6, 65-78.

- Sabatini, F., & Sarracino, F. (2014). Will Facebook save or destroy social capital? An empirical investigation into the effect of online interactions on trust and networks. Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/53325/

- Soldatova, G.U., & Nestik, T.A. (2010). Youth in the network: strength and weakness of social capital. Obrazovatel'naya politika, (3-4), 24-40 (in Russian).

- Soldatova, G.U., & Olkina O. (2016). 100 friends. Circle of communication of adolescents in social networks. Deti v informacionnom obshchestve, 24, 24-33 (in Russian).

- Soldatova, G.U., & Rasskazova E.I. (2016). Models of digital competence and online activity of Russian. Nacional'nyj psihologicheskij zhurnal, 2(22), 50-60 (in Russian).

- Wellman, B., & Hampton, K. (2001). Long Distance Community in the Network Society: Contact and Support Beyond Netville. American Behavioral Scientist, 45(3), 477-96.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 November 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-048-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

49

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-840

Subjects

Educational psychology, child psychology, developmental psychology, cognitive psychology

Cite this article as:

Soldatova, G. U., & Chigarkova, S. V. (2018). Social Capital Online: Intergenerational Analysis. In S. Malykh, & E. Nikulchev (Eds.), Psychology and Education - ICPE 2018, vol 49. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 636-643). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.11.02.73