Abstract

The current study focuses on examining the Dark Triad of personality traits (Machiavellism, narcissism, and psychopathy) in representatives of the professional community of teachers belonging to three different levels of the education system. Accordingly, the participants represented three different professional groups of educators: 154 kindergarten teachers, 147 school teachers and 101 university teachers. The total sample comprised 402 participants including 372 women and 30 men aged from 19 to 84 years old (

Keywords: The Dark Triad of personalityeducatorskindergarten teachersschool teachersuniversity teachers

Introduction

The psychological study of such personal traits as Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy (a complex of which is now called the Dark triad of personality) began in the late 19th century, although it was preceded by a long period of contemplation about these traits in the framework of philosophy, medicine, pedagogy, etc.

As a result, psychologists have come to the study of personal features of the Dark Triad based on the significant experience of their predecessors. On this nutritious ground, in the late 19th and early 20th century, many psychologists launched the study of dark personality traits. In particular, narcissism was studied by H. Ellis, S. Freud, P. Nacke et al. (see, e.g., Freud, 1957), psychopathy (as borderline, subclinical syndrome) – by V.M. Bekhterev, S. Freud, Е. Kraepelin et al. (see, e.g., Litvintsev, 2017), and Machiavellianism (as a tendency to manipulate people) – by V.M. Bekhterev, S. Freud, C.G. Jung, W. Stern et al. (see, e.g., Bekhterev, 1998, Bereczkei, 2017).

Throughout the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century (to date), each of the traits of the future Dark Triad was widely studied and received many measuring tools (see, e.g., Chen, 2018, Muris, Merckelbach, Otgaar, & Meijer, 2017).

Thus, individually Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy have been studied in psychology for about a century and a half. At the same time, since the 1990s, a theoretical approach has been developing, within which these personality traits are considered as interrelated manifestations of a common generalized complex – the Dark Triad of personality. In the framework of this study, we rely on the most well-known approach suggested by Paulus and Williams (2002).

The studies of the Dark triad of personality over the past 20 years showed conflicting results. On the one hand, the consideration of Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy within a single complex has been quite productive: many studies have identified significant relationships between the Dark Triad traits, and their joint determining or moderating influence on behaviour, occupational activities, psychological well-being and other aspects of human life (see, e.g., Cohen, 2016). On the other hand, the concept of the Dark Triad has been repeatedly questioned. For example, many authors note that the relationship between psychopathy and Machiavellianism is much stronger than between narcissism and each of these traits; it has been proposed to reduce the Dark Triad to a Dark Dyad (see, e.g., Persson, Kajonius, & Garcia 2017, Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2018).

However, other authors provide a rationale for the need to expand the Dark Triad – in particular, to the Dark Tetrad (see, e.g., Thomaes, Brummelman, Miller, & Lilienfeld, 2017). Another point of view suggests that the Dark side of the personality is extremely diverse and heterogeneous, so there are many more of its manifestations (traits) than two, three or four (Thomaes et al., 2017, Zeigler-Hill, Besser, Morag, & Campbell, 2016).

The current situation might be assessed as a state of unstable equilibrium: the proponents of each of these positions cite convincing arguments to support it, but this is not enough to refute the competing positions. Under these conditions, the concept of the Dark Triad seems to be the most balanced position potentially allowing for its transformation in the direction of increasing as well as reducing the number of basic traits of the Dark side of personality. At the same time, further development of the conceptual foundations of the Dark side of personality should be based on evidence obtained from empirical studies including various professional groups. However, the dominant trend in the Dark Triad research in recent years has been the use of non-profession-specific samples:

student samples (see, e.g., Azizli et al., 2016, Dowgwillo & Pincus, 2017, Jonason, 2015a, Schneider, McLarnon, & Carswell, 2017);

virtual samples recruited via Internet services such as МТurk, GoogleDocs etc. (see, e.g., Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2017, 2018, Jonason, 2015b);

population samples (see, e.g., Anderson, & Cheers, 2017, Malesza, Ostaszewski, Büchner, & Kaczmarek, 2017, Vater, Moritz, & Roepke, 2018).

Nevertheless, profession-specific samples are used in few studies (e.g., Tijdink et al., 2016). However, the proportion of studies conducted on such samples in the total amount of Dark Triad research remains small, and many professions have almost not been studied.

Problem Statement

In the Dark Triad studies, underinvestigated professional groups include teachers representing different levels of education, in particular, kindergarten, school and university teachers.

On the one hand, personality and professional activity of teachers of each of these groups in recent years has been intensively studied. In particular, research on school teachers is widely presented (see reviews in Göncz, 2017, Klassen et al., 2018, Stronge, 2018). In recent years, research has been intensively expanding both on samples of kindergarten teachers (e,g,, see review in Lenkov, Rubtsova, & Nizamova, 2017) and university teachers (see, e.g., Tan, Mansi, & Furnham, 2018).

On the other hand, empirical studies of the Dark triad of personality on these groups are rare. For example, O'Boyle, Forsyth, Banks, and McDaniel (2012) performed a meta-analysis that included over 180 Dark Triad studies covering many professions (police officers, salesmen, etc.) but not educators (see O'Boyle, Forsyth, Banks, & McDaniel, 2012).

This situation complicates the comparative analysis of these groups of teachers and the appropriate evidence-based conceptual development of the Dark side of personality.

Research Questions

This study addresses the following research questions:

To what extent the Dark triad personality traits are expressed in representatives of professional groups consisting of kindergarten, school and university teachers?

Are there any significant differences between these groups in the expression of the Dark Triad personality traits?

Can we say that the factor of the level of education system (with gradations "kindergarten", "school" and "university") significantly affects the expression of the Dark Triad personality traits among teachers?

Is the structure of the Dark Triad traits the same for these three related professional groups, or does each trait have a similar yet specific structure?

How does the expression and structure of the Dark triad personality traits of teachers from different groups correlate with similar results obtained in other social and professional groups?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of the study was to identify the degree of expression of the Dark Triad personality traits as well as the possible specificity of their structure in the context of a comparative analysis of three related professional groups of teachers: kindergarten teachers, school teachers and university teachers.

Research Methods

Conceptual framework

The Dark Triad of personality is considered in accordance with the conceptual notions suggesting that Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy are three relatively independent personality traits, which however have significant relationships and therefore can be considered as a single complex – integral substructure of the personality determining and mediating various negative manifestations of consciousness, behavior, interpersonal and professional relationships (Paulhus & Williams, 2002; Jones & Paulhus, 2014).

Professional groups of educators are considered in accordance with the Russian system of education and professional activity of teachers representing different levels of the system: kindergarten, school and university teachers.

Participants and procedure

Teachers from three different levels of education were invited to participate in the study. Accordingly, the final sample of the study included three professional groups:

154 kindergarten teachers – all females aged from 19 to 58 years old (M = 31.93, SD = 10.44), with work experience ranging from 0.5 to 33 years (M = 7.90, SD = 8.83); this group is supplemented by a sample of n = 129, which was used in our previous study (Lenkov, Rubtsova, & Nizamova, 2017);

147 school teachers including 135 females (91.8%) and 12 males (8.2%), aged from 21 to 68 years old (M = 32.09, SD = 9.25), with work experience ranging from 0.5 to 40 years (M = 10.01, SD = 9.40);

101 university teachers including 83 females (92.5%) and 18 males (7.5%) aged from 22 to 84 years old (M = 33.57, SD = 11.49), with work experience ranging from 0.5 to 57 years (M = 10.27, SD = 11.20).

The characteristics of the overall sample were as follows: 402 teachers including 372 females (82.2%) and 30 males (17.8%) aged from 19 to 84 years old (M = 32.40, SD = 10.30), with work experience ranging from 0.5 to 57 years (M = 9.27, SD = 9.71).

Educational institutions (kindergartens, schools and universities) in which the participants worked at the time of the study were located in several regions of Russia including the cities of Moscow, St. Petersburg, Tver, Ulyanovsk and the corresponding districts.

All participants of the study were volunteers and gave informed consent. Participants filled out questionnaires on general information and on the expression of the Dark Triad traits.

The measured variables and the research design

We used three groups of measured variables:

independent variables represented by three levels of education system: preschool education (kindergarten teachers), school education (school teachers), higher education (university teachers);

dependent variables: three traits of the Dark triad of personality (Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy), and the overall score defined as the arithmetic mean of these three traits;

other controlled variables: age and work experience.

The design of the study included:

calculation of means and intercorrelations of the Dark Triad traits in each group of teachers;

inter-group comparisons between these groups using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA);

comparison of the results obtained on the expression and structural features of the Dark triad traits in teachers with similar research results obtained by other authors on other social and professional groups.

Measures

The Dark Triad. To measure the traits of the Dark Triad, we used the "Short Dark Triad (SD3)" questionnaire (Jones & Paulhus, 2014) adapted in the Russian language (Egorova, Sitnikova, & Parshikova, 2015). This questionnaire consists of 27 items and includes three subscales – Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy (9 items per each). The statements are evaluated on a 5-point Likert scale with gradation from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. The questionnaire has satisfactory psychometric properties: for Machiavellianism, narcissism, and psychopathy the Cronbach's alpha is equal to .74, .72, .70, respectively (Egorova et al., 2015).

Age was determined as the number of full years at the time of the study.

Work experience was defined as the number of years of work in the profession, rounded to .5.

Data analysis

Statistical methods used to analyze the data included one-way analysis of variation (ANOVA), supplemented by post hoc tests; correlation analysis (Pearson correlations); methods of testing statistical hypotheses (Fisher criteria, Levene’s test, etc.).

Findings

Comparison of the Dark Triad traits between groups of teachers

Table

Table

Application of ANOVA in this study had the following features associated with the choice of post hoc tests for multiple comparisons:

for Machiavellianism and the overall expression of the Dark Triad we used a post hoc Scheffe test assuming equality of variances; in addition, due to differences in the groups size, we additionally used a post hoc Games-Howell test allowing, in particular, for differences in the group sizes (e.g., see Field, 2009); however, this test showed essentially the same results as the Scheffe test, therefore in Table

02 its results for Machiavellianism and the overall score of the Dark Triad are not shown;in turn, for narcissism and psychopathy a number of post hoc tests involving inequality of variances were used in ANOVA (Tamhane test etc.); in Table

02 , only the results of the post hoc Games-Howell test are shown, which allows for differences in both variance and group size (see, e.g., Field, 2009) since other post hoc tests gave similar results.

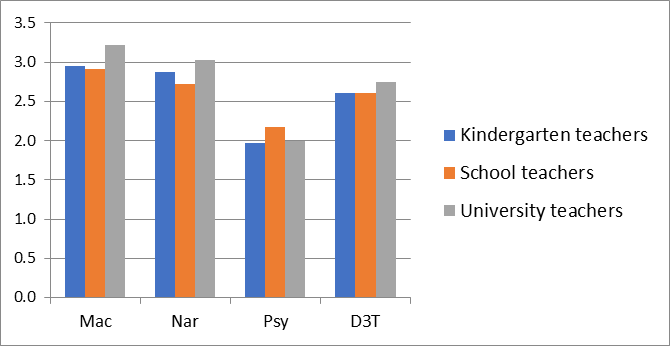

As can be seen from Table

Comparison of the results presented in Tables

the level of Machiavellianism does not differ statistically between kindergarten teachers and school teachers but is significantly higher (p < .01) in university teachers than in the other two groups;

the lowest level of narcissism is observed in school teachers differing significantly from kindergarten (p < .05) and university teachers (p < .01), with university teachers showing the highest level, which is significantly higher (p < .05) than in kindergarten teachers;

the level of psychopathy does not differ among kindergarten teachers and university teachers, but is significantly higher for school teachers than for kindergarten teachers (p < .01) and university teachers (p < .05);

the overall score of the Dark Triad does not differ for kindergarten teachers and school teachers, but is significantly higher for university teachers than for kindergarten (p < .01) and school teachers (p < .01).

Figure

Thus, the results of ANOVA suggest that the factor of the level of the education system at which a teacher works affects the expression of the Dark Triad traits in an ambiguous way:

for Machiavellianism and the overall score for the Dark Triad, it leads to an increase in the transition from the school level to the university level;

in contrast, there is a drop in the level of narcissism in school teachers with a subsequent significant increase in university teachers;

finally, unlike the first two cases, for psychopathy there is a "peak" of the level in school teachers with a subsequent decrease in university teachers almost to the lowest level of kindergarten teachers.

The revealed empirical regularities allow us to assume that the structure of the Dark Triad of personality changes non-linearly under the influence of the factor of the level of teachers’ professional activity in the educational system.

Table

Table

Kindergarten teacher. The level of Machiavellianism among kindergarten teachers obtained in this study is consistent with the results reported by Jonason, Wee, Li and Jackson (2014) [SС = C5, p = .247] but significantly lower than the level reported for women groups by Egorova, Sitnikov, and Parshikova (2015) [SC = C1, p = .005] and Jones and Paulhus (2014) [SC = C3, p = .000]. The level of narcissism in kindergarten teachers obtained in this study does not statistically differ from the result, which was reported by Jones and Paulhus (2014) [p = .080] but significantly higher than the results by Jonason et al. (2014) [p = .000] and the results on a group of women reported by Egorova et al. (2015) [p = .038]. The level of psychopathy among kindergarten teachers obtained in this study is consistent with the results for groups of women reported by Egorova et al. (p = .860) and Jones and Paulhus (2014) [p = .856] but significantly higher than the levels reported by Jonason et al. (p = .029).

Thus, the expression of Machiavellianism, narcissism and psychopathy among teachers in general and different groups has its specifics – professional, on the one hand, and cross-cultural on the other hand.

Comparison of the Dark Triad traits correlations across studies

For the comparison of correlations in the structure of the Dark Triad traits, we only used those studies presented in Table

Based on the data presented in Tables

Thus, some results of our study are in good agreement with the results of other studies, while others are significantly different, which makes them most interesting as it is possible to identify the professional and cross-cultural specificity of the concerned groups of teachers.

The types of the Dark Triad traits structure

The comparison of the results of our study with many other studies on the Dark Triad of personality measured with the same tool, the short Dark Triad (SD3), has allowed us to conclude that there are at least three qualitatively different types of structure of the Dark Triad traits from in terms of intercorrelations between the Dark Triad traits.

Conventionally and schematically, these types can be designated as follows:

Type 1 can be called a "full triad", with strong associations between all the traits of the triad; this type is the most common and is found in studies conducted on samples of students, population samples, random MTurk samples et al. (see, e.g., Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2017, Jonason, 2015b); this type is also revealed for some professional samples (e.g., Tijdink et al., 2016);

Type 2 can be called a "weakened triad", with two of the three intercorrelations of the Dark Triad traits being sufficiently strong, among which there is necessarily a correlation of Machiavellianism with psychopathy, but one of the correlations is much weaker than the other two, or completely disappears (becomes non-significant); therefore, this weakened correlation might be the correlation of narcissism with either Machiavellianism or psychopathy: the first case was identified, for example, in the studies of Jones and Paulhus (2014), Jonason, Wee, Lee, and Jackson (2014), as well as in this study for kindergarten teachers and teachers in general (see Table

01 ); the second type was identified, for example, in a study by Jonason, Baughman, Carter, and Parker (2015);Type 3 (Dyad) describes the situation when the correlation of Machiavellianism and psychopathy is quite high, while the correlations of narcissism with Machiavellianism and psychopathy are significantly weaker or absent (non-significant); this type was identified in this study for school and university teachers (see Table

01 ).

For type 3 (Dyad) identified in our study, we did not find any cases of its manifestation in the results of other studies conducted using the questionnaire "Short Dark Triad (SD3)" (Jones & Paulhus, 2014). However, this type is similar to the above-mentioned version of the structure of the Dark Triad, which includes two elements: one is narcissism, and the second one is a factor formed by the joint influence of Machiavellianism and psychopathy (see, e.g., Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2018). At the same time, complex, changeable associations among the Dark Triad traits support the idea that Machiavellianism, psychopathy and narcissism are complex systems consisting of many separate personality traits, and therefore should be viewed as multidimensional configurations of traits (e,g, Thomaes, Brummelman, Miller, & Lilienfeld, 2017, p. 835).

Conclusion

In general, the results obtained in this study provide confirmation of the following regularities:

for different professional groups of teachers the expression of the Dark Triad traits changes non-linearly under the influence of the factor of the level of teachers’ professional activity in the education system;

the effect of the level of professional activity differs for different traits of the Dark Triad;

there are different types of the structure of the Dark Triad traits manifested in certain social or professional groups;

school teachers are characterized by the highest (among all examined groups of teachers) levels of psychopathy; this fact should be taken into account in the organization of work on the preservation of mental health and prevention of professional deformations in the personality;

university teachers are characterized by the highest (among all the examined groups of teachers) levels of Machiavellianism; this fact should be taken into consideration in the context of the universities functioning and development of productive organizational culture.

The lack of data of independent studies conducted on the same groups of teachers makes it difficult to assess the reliability (non-randomness) of the identified effects; accordingly, it is necessary to reproduce the identified patterns on new independent samples of teachers of different levels of the education system.

References

- Anderson, J., & Cheers, C. (2017). Does the Dark Triad predict prejudice?: The role of Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism in explaining negativity toward asylum seekers. Australian Psychologist, 53(3), 271–281.

- Azizli, N., Atkinson, B. E., Baughman, H. M., Chin, K., Vernon, P. A., Harris, E., & Veselka, L. (2016). Lies and crimes: Dark Triad, misconduct, and high-stakes deception. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 34–39.

- Bekhterev, V. M. (1998) Suggestion and its role in social life (L.H. Strickland, Ed. & Trans.). New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction. (Original work published 1903)

- Bereczkei, T. (2017). Machiavellianism: The Psychology of Manipulation (1st ed.). London, UK: Routledge.

- Birkás, B., Gács, B., & Csathó, Á. (2016). Keep calm and don't worry: Different Dark Triad traits predict distinct coping preferences. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 134–138.

- Chen, B.-B. (2018). The associations between social rank uncertainty, Machiavellianism, and dominance: From a life history perspective. Evolutionary Psychology, 16(2), 1–6.

- Cohen, A. (2016). Are they among us? A conceptual framework of the relationship between the dark triad personality and counterproductive work behaviors (CWBs). Human Resource Management Review, 26(1), 69–85.

- Dowgwillo, E. A., & Pincus, A. L. (2017). Differentiating Dark Triad traits within and across Interpersonal circumplex surfaces. Assessment, 24(1), 24–44.

- Egan, V., Chan, S., & Shorter, G. W. (2014). The Dark Triad, happiness and subjective well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 17–22.

- Egan, V., Hughes, N., & Palmer, E. J. (2015). Moral disengagement, the dark triad, and unethical consumer attitudes. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 123–128.

- Egorova, M. S., Sitnikova, M. A., & Parshikova, O. V. (2015). Adaptation of the Short Dark Triad. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 8(43).

- Field, A. P. (2009). Discovering statistics using SPSS (3rd ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2009.

- Freud, S. (1957). On narcissism: an introduction. In J. Strachey (Ed.), The standard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (Vol. 14, pp. 67–102).

- Göncz, L. (2017). Teacher personality: a review of psychological research and guidelines for a more comprehensive theory in educational psychology. Open Review of Educational Research, 4(1), 75–95.

- Jonason, P. K. (2015a). How «dark» personality traits and perceptions come together to predict racism in Australia. Personality and individual differences, 72, 47–51.

- Jonason, P. K. (2015b). The deceleration and increased cohesion of the Dark Triad traits over the life course. Psikhologicheskie Issledovaniya, 8(43).

- Jonason, P. K., Baughman, H. M., Carter, G., & Parker, P. (2015). Dorian Gray without his portrait: Psychological, social, and physical health costs associated with the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 78, 5–13.

- Jonason, P. K., Wee, S., Li, N. P., & Jackson, C. (2014). Occupational niches and the Dark Triad traits. Personality and Individual Differences, 69, 119–123.

- Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the Short Dark Triad (SD3): A brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28–41.

- Klassen, R. M., Durksen, T. L., Hashmi, W. A., Kim, L. E., Longden, K., Metsäpelto, R.- L., . . . Györi, J. G. (2018). National context and teacher characteristics: Exploring the critical non-cognitive attributes of novice teachers in four countries. Teaching and Teacher Education, 72, 64–74.

- Lenkov, S. L., Rubtsova, N. E., & Nizamova, E. S. (2017). The Dark Triad of personality and work efficiency of kindergarten teachers. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences, 33, 196–211.

- Litvintsev, S. V. (2017). About the borderlines of psychopathies. Review of psychiatry and medical psychology, 1, 11-18.

- Malesza, M., Ostaszewski, P., Büchner, S., & Kaczmarek, M.C. (2017). The adaptation of the Short Dark Triad personality measure – psychometric properties of a German sample. Current Psychology. 1-10. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9662-0

- Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., & Meijer, E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the Dark Triad (narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 183–204.

- O'Boyle, E. H., Forsyth, D. R., Banks, G. C., & McDaniel, M. A. (2012). A meta-analysis of the Dark Triad and work behavior: A social exchange perspective. Journal of Applied Psychology, 97(3), 557–579.

- Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 6(6), 556–563.

- Persson, B. N., Kajonius, P. J., & Garcia, D. (2017). Revisiting the structure of the Short Dark Triad. Assessment [Epub ahead of print]. doi: 10.1177/1073191117701192

- Rogoza, R., & Cieciuch, J. (2017). Structural investigation of the Short Dark Triad questionnaire in Polish population. Current Psychology. doi: 10.1007/s12144-017-9653-1

- Rogoza, R., & Cieciuch, J. (2018). Dark Triad traits and their structure: An empirical approach. Current Psychology, doi: 10.1007/s12144-018-9834-6

- Schneider, T. J., McLarnon, M. J. W., & Carswell, J. J. (2017). Career interests, personality, and the Dark Triad. Journal of Career Assessment, 25(2), 338–351.

- Stronge, J. H. (2018). Qualities of effective teachers (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

- Tan, S., Mansi, A., & Furnham, A. (2018). Student preferences for lecturers' personalities. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 42(3), 429–438.

- Thomaes, S., Brummelman, E., Miller, J. D., & Lilienfeld, S. O. (2017). The dark personality and psychopathology: Toward a brighter future. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 126(7), 835–842.

- Tijdink, J. K., Bouter, L. M., Veldkamp, C. L. S., van de Ven, P. M., Wicherts, J. M., & Smulders, Y. M. (2016). Personality traits are associated with research misbehavior in Dutch scientists: A cross-sectional study. Plos One, 11(9):e0163251.

- Vater, A., Moritz, S., & Roepke, S. (2018). Does a narcissism epidemic exist in modern western societies? Comparing narcissism and self-esteem in East and West Germany. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0188287.

- Zeigler-Hill, V., Besser, A., Morag, J., & Campbell, W. K. (2016). The Dark Triad and sexual harassment proclivity. Personality and Individual Differences, 89, 47–54.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

23 November 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-048-8

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

49

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-840

Subjects

Educational psychology, child psychology, developmental psychology, cognitive psychology

Cite this article as:

Lenkov, S. L., Rubtsova, N. E., & Nizamova, E. S. (2018). The Dark Triad Of Personality In Kindergarten, School And University Teachers. In S. Malykh, & E. Nikulchev (Eds.), Psychology and Education - ICPE 2018, vol 49. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 352-367). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.11.02.39