Abstract

The basic notions of attachment theory, originally devoted to the bond between child and primary caregiver, were conceptualized in romantic attachment. Albeit the classical attachment styles were described in adulthood (

Keywords: Romantic attachmentsignificant otherinternal working modeltwo-dimensional model of individual differences in romantic attachment

Introduction

The ideas of the model of self development within the relationship with significant other date back to the psychoanalysis and the object relations theory. The consideration of primary caregiver as a guarantee of a harmonic emotional development who responds to the child’s basic needs, in J. Bowlby’s attachment theory, was expanded with the concept of internal working model as mental representation of self and others (Bowlby, 1969, 1979). These cognitive schemes derive from the interaction with the attachment figure where the self-awareness is realized, and this interaction further influences on the interpersonal relationship development. Several studies of romantic attachment (Hazan & Shaver, 1987; Bartholomew & Horowitz, 1991) employed the model of self and the model of other(s) as components of internal working model: the self-perception as the one who deserves to be loved and accepted, and the perception of other as available and supporting.

The interrelation between behavioral patterns of attachment and internal working models is mutually directed (Andersen et al., 2002; López, 1993; Mikulincer & Shaver, 2012): individuals who show less insecure attachment patterns tend to demonstrate more caregiving behaviors (Carnelley et al., 1996; Feeney & Collins, 2001). Furthermore, albeit numerous studies on influence of one’s attachment patterns on relationship quality were conducted (e.g., Butzer & Campbell, 2008; Towler & Stuhlmacher, 2013), exists the dyadic perspective which reflects classic ideas of internal working models origin: the dimensions of avoidance and anxiety (basic parameters for two-dimensional model of individual differences of romantic attachment) in oneself and his/ her romantic partner are interrelated. The attachment insecurity indicators and its’ perception in couples members are related with relationship satisfaction (Molero et al., 2016).

The identification mechanism contributes to the model of self constitution through the significant other: arising in mother-infant interaction, intimate relationships with peers, romantic partners and own children are constituted, these attachment figures significance differs across the lifespan. In the present study we focused on the model of significant other as a component of internal working model of attachment, the model of other (i.e., romantic partner) was described on conscious and subconscious levels.

Problem Statement

Numerous studies of mother – infant attachment were realized in Russian sample, but the romantic attachment and its’ qualitative aspects have not been considered.

Research Questions

Do the specific patterns described in two-dimensional model of individual differences in romantic attachment reply in Russian sample?

Which are the main characteristics of the model of significant other in young adults with different romantic attachment styles?

Purpose of the Study

The aim of present study was to identify patterns specific for the model of other in different romantic attachment styles both on conscious and subconscious levels.

Research Methods

Sample

101 individuals participated in the present study. Their age ranged from 21 to 39 years (M = 27.62, SD = 5.39). 37 men and 64 women, 72.3% in civil marriage, and the rest were living together. 65.3% of the participants completed higher education program, 25.7% were undergraduate students, 4% and 5% completed secondary school and specialized professional training school respectively. The majority of them studied humanities (52%), 20% studied technology, 10% - science, and 18% were psychologists.

Method and procedure

The M.V. Yaremchuk’s questionnaire in G.V. Burmenskaya and O.V. Almazova modification (Yaremchuk, 2006; Almazova, 2015) was used to assess the attachment to mother. In consists of 11 items, each of them has 3 options for multiple choice corresponding to 3 classical attachment styles (secure, anxious-avoidant and anxious-ambivalent). The participants were asked to choose the most appropriate option in each question, then the attachment style was defined by the result calculated;

The Experiences in Close Relationships-Revised (ECR-R) Questionnaire (Fraley, Waller, Brennan & 2000) assesses the romantic attachment using the two-dimensional model of individual differences of romantic attachment. It contains 36 items related to “anxiety” or “avoidance” scales. The participants answered using a 7-point scale ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 7 (completely agree);

The semantic differential consisted of 10 pairs of adjectives to evaluate oneself and his/ her spouse or romantic partner using a scale ranging from -3 to 3:

The 5-factor Inventory of Individual Differences (Davey, Eaker & Walters, 2003), It contains 108 personal characteristics to be evaluated with 7-point scale.

Findings

The assumption of succession in attachment across the lifespan was confirmed in the present study: the Pearson Chi-Square criterion (χ²=12.830; p=0.005) suggests that two groups with secure and insecure attachment to mother (38,4 and 61,6% respectively) differ significantly in romantic attachment styles distribution. The secure attachment to spouse or romantic partner was evenly distributed in two groups with secure and insecure attachment to mother, while insecure romantic attachment styles were significantly more presented in the group with insecure attachment to mother.

In order to find out the differences in scale values for ECR-R questionnaire in individuals with secure and insecure attachment to mother we used Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. Different scale values were discovered for individuals with secure and insecure attachment to mother (U=1809, p ≤0.001 for “Anxiety” scale): secure-attached young adults report significantly less anxiety in relationship with spouse or romantic partner than persons with insecure attachment to mother. Furthermore, secure- and insecure-attached to mother individuals differ in avoidance level (U=2137, p ≤0.047 for “Avoidance” scale): persons with secure attachment to mother show significantly less avoidance in relationship with spouse or romantic partner than insecure-attached ones. As we verified coherence and consistency of the constructs mentioned above, the main part of the study was realized. It contained conceptual filling of K. Bartholomew & L.M. Horowitz’s two-dimensional model of individual differences in romantic attachment in Russian sample, and specification of the model of significant other at conscious and subconscious levels.

The ECR-R questionnaire results were used to divide the participants in 3 groups by the romantic attachment style (we introduced such variable as the sum of scale values of ECR-R questionnaire in order to define total level of insecure attachment patterns manifestation): individuals were referred to groups with secure, conventionally secure and insecure romantic attachment. Approximate 33% and 66% points in scale values distribution (4.28 for 32.7% and 5.89 for 67.3% respectively) were employed to assign a group number to each participant. The extreme groups comparison method was used to test our hypotheses.

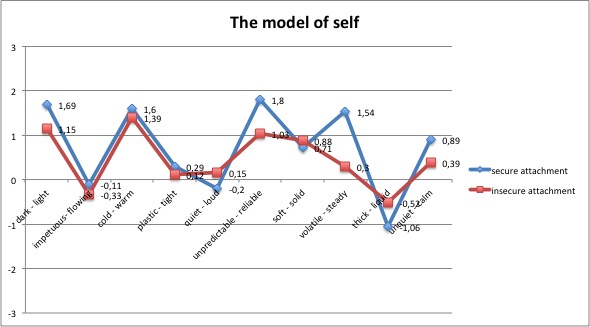

To define a baseline we offered the participants to evaluate themselves using the semantic differential (Figure

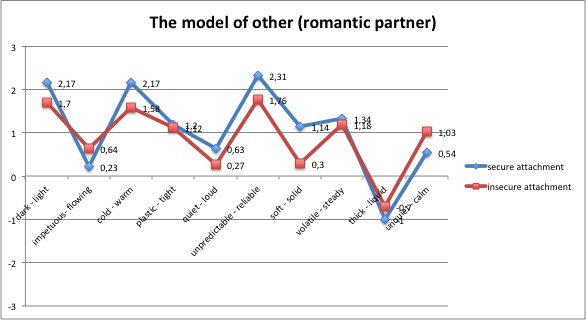

The study of significant other’s representations at subconscious level with semantic differential discovered significant differences (Mann-Whitney test) for “warm – cold” (U=408; p=0.03) scale and a tendency for “soft – solid” (U=427,5; p=0.06) scale (Figure

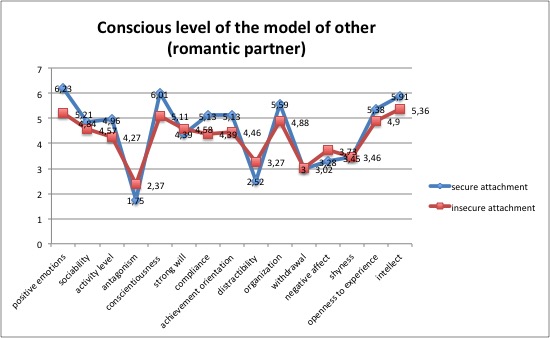

The conscious level of the model of other was assessed by 5-factor Inventory of individual differences. Significant differences (Mann-Whitney test) were found for “positive emotions” (U=170; p=0.00), “activity level” (U=392.5; p=0.02), “antagonism” (U=352.5; p=0.01), “conscientiousness” (U=241.5; p=0.00), “compliance” (U=324.5; p=0.002), “achievement orientation” (U=338.5; p=0.003), “distractibility” (U=398.5; p=0.03), “organization” (U=359.5; p=0.01), “openness to experience” (U=359; p=0.01), “intellect” (U=343.5; p=0.004) scales (Figure

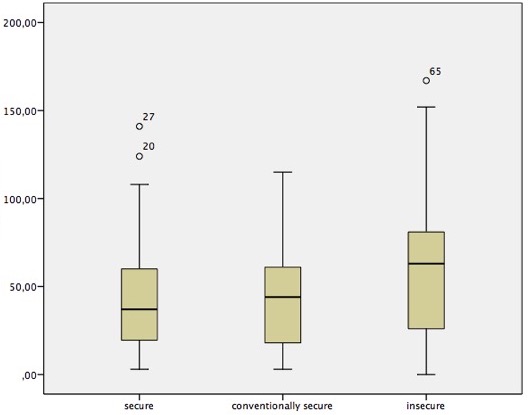

In order to study the identification with spouse or romantic partner we introduced another variable, the sum of squares of subjective distance from the semantic differential scale values for self to its’ scale values for significant other. Comparing 2 groups with secure and insecure attachment to romantic partner, we found a tendency (U=430; p=0.07) to evaluate oneself similarly as his/ her spouse (romantic partner) in secure-attached young adults (Figure

Conclusion

Generalizing the obtained data of the study on the model of significant other, we can conclude that the hypothesis about the interrelation between the model of significant other and romantic attachment style is confirmed: our data suggests that the model of spouse or romantic partner differs significantly in 2 groups with secure and insecure romantic attachment. For insecure-attached individuals, the significant other (i.e. spouse or romantic partner) appears to be ambivalent and carries both positive and negative patterns: albeit the significant other is perceived as insensitive, distant and rigid, almost antagonistic, tidiness, learnability, curiosity and reliability are reported. A tendency we found in identification with spouse or romantic partner explains that secure-attached individuals tend to describe themselves similarly to their spouse or romantic partner, this means feeling of unity and solidarity in couple, shared emotional space; while insecure-attached participants experienced spouse or romantic partner’s detachment and emotional distance.

The level of mother-infant attachment security was correlated with the level of romantic attachment security. The attachment to mother (or its’ reconsideration in adulthood) continues to make its’ impact on the characteristics of relationship with spouse or romantic partner. The present study presents one more illustration of how the infant-mother attachment impacts on the emotional and social development across the lifespan, particularly on the interpersonal relationships. The obtained data on the differences of the model of significant other in young adults with different romantic attachment styles could serve as conceptual filling of K. Bartholomew & L.M. Horowitz’s two-dimensional model of individual differences in romantic attachment in Russian sample, it suggests general cross-cultural patterns: the characteristics we found not only correspond this model, but also permit to specify the intimate relationship experience in each case and to define the problem area, which is the most valuable practical effect for family counseling and psychotherapy. The interrelation between constructs mentioned above presumes the existence of more generalized domain connecting them, in particular, we prefer to highlight the internal working models, what reminds of child-parent relationship content. Therefore, the present work confirmed general cross-cultural patterns in romantic attachment and filled theoretical representations about the model of self and significant other in Russian sample.

References

- Almazova O.V. (2015). Attachment to mother as a factor of sibling relationship in adulthood. Diss. PhD, Moscow,. [in Russian]

- Andersen, S. M., Chen, S., & Miranda, R. (2002). Significant others and the self. Self and Identity, 1(2), 159-168.

- Bartholomew K, Horowitz LM. (1991). Attachment styles among young adults: A test of a four-category model. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology; 61(2):226–244.

- Bowlby, J. (1969). Attachment and loss: Vol. 1. Attachment. New York: Basic Books.

- Bowlby, J. (1979). The making and breaking of affectional bonds. London: Routledge.

- Butzer, B. and Campbell, L. (2008), Adult attachment, sexual satisfaction, and relationship satisfaction: A study of married couples. Personal Relationships, 15: 141–154.

- Carnelley K.B., Pietromonaco P.R., Jaffe K. (1996). Attachment, caregiving, and relationship functioning in couples: Effects of self and partner. Personal Relationships. 3(3):257–277.

- Davey, M., Eaker, D. G., & Walters, L. H. (2003). Resilience processes in adolescents: Personality profiles, self-worth, and coping. Journal of adolescent research, 18(4), 347-362.

- Feeney,B.C., & Collins,N.L. (2001). Predictors of caregiving in adult intimate relationships: An attachment theoretical perspective. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80, 972 – 994.

- Fraley, R. C., Waller, N. G., & Brennan, K. A. (2000). An item response theory analysis of self-report measures of adult attachment. Journal of personality and social psychology, 78(2), 350.

- Hazan C, Shaver PR. (1987). Romantic love conceptualized as an attachment process. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology.; 52(3):511–524.

- López, F. (1993). El apego a lo largo del ciclo vital. In M. J. Ortiz & S. Yárnoz (Eds.), Teoría del apego y relaciones afectivas (pp. 11-62). Bilbao: Servicio Editorial de la Universidad del País Vasco.

- Mikulincer, M., & Shaver, P. R. (2012). Adult attachment orientations and relationship processes. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 4(4), 259-274.

- Molero, F., Shaver, P. R., Fernandez, I., Alonso‐Arbiol, I., & Recio, P. (2016). Long‐term partners' relationship satisfaction and their perceptions of each other's attachment insecurities. Personal Relationships, 23(1), 159-171.

- Towler, A. J., & Stuhlmacher, A. F. (2013). Attachment styles, relationship satisfaction, and well-being in working women. The Journal of social psychology, 153(3), 279-298.

- Yaremchuk M.V. (2006). Attachment to parents role in romantic relationship in adolescence, Diss. PhD, Moscow, [in Russian]

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

13 July 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-042-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

43

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-694

Subjects

Child psychology, developmental psychology, child care, child upbringing, family psychology

Cite this article as:

Chursina, A. V., & Almazova, O. V. (2018). Model Of Significant Other In Young Adults With Different Romantic Attachment Style. In S. Sheridan, & N. Veraksa (Eds.), Early Childhood Care and Education, vol 43. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 626-633). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.07.83