Abstract

Psychological security acts as a foundation for the individual’s insight and evaluation of the surrounding objects and situations, and as a factor of orientation and determination of learning the world by the person. Security perceptions form individually; they represent a subjective reflection of reality. The teenager’s psychological security is a necessary condition for the continuous growth and development enhancing his maturity, independence and self-sustaining. Despite recent extensive research on security issues, the specifics of teenagers’ perception of security as a condition for personality development have not been dealt with so far. The present study aims at identifying the specificity of the adolescents’ security perceptions. The study make use of the semantic differential method and the technique offered by D.Peabody, in which the following states are assessed: “Me now”, “Me in the past”, “Me in the future”, “Me in danger” and “Me secure”. The sampling selected in line with the study goal consists of two groups: schoolchildren aged 14-15 and adults aged 25-40. The study conducted shows that upon differentiating danger/security situations, the adolescents resort to the same factors as the older respondents. However, the processes of the situation assessment and behaviour pattern`s choice differ. The data obtained underline the necessity to devise a special training aimed at preparing the teenagers for secure interaction with dangerous situations since in the course of teenagers’ vital activity, the experience of dealing with dangerous situations is accumulated spontaneously, and it doesn`t provide the formation of their self-confidence in case of facing dangers and threats.

Keywords: Psychological securityteenagerssecurity perceptions

Introduction

Psychological security as a socio-psychological phenomenon plays a significant role in human life. It acts as a foundation for the individual’s insight and evaluation of the surrounding objects and situations and a factor of orientation and determination of the person’s learning the world.

Psychological security is a state of personality when the individual can satisfy his/her basic needs for self-preservation and be aware of his/her own (psychological) security in society (Zotova, 2011. P. 134). Personality security can be also seen as the person’s confidence in his abilities based on his own knowledge, skills and inner resources to cope with new threats and dangerous situations. Security means that in need other people (parents, teachers, peers, friends, wife/husband, etc.) can come to help, when there exists a “safety net” in time of troubles.

M. Little and R. Kobak studies the impact of security on children’s self-esteem and found that when children feel emotionally secure they have fewer conflicts with teachers and their peers at school (Little & Kobak, 2003). The lack of security also influences the degree of self-respect (Little & Kobak, 2003) and social competence (Helson & Wink, 1987). Children who feel secure are described as well-adjusted, capable of trusting and understanding. They use their social knowledge and skills to the benefit of mutual relationships, for instance, through cooperation (Suess & et al., 1992). At school “secure” children get on well with their peers (Scheider & et al., 2001), they demonstrate less aggressive behaviour towards their friends (Zimmerman & et al., 2001), display more empathy towards strangers in misery (Van der Mark & et al., 2002).

When a threat is real “insecure” people tend to choose negative, inadequate responses (danger avoidance or taking things too hard), whereas “secure” people, as a rule, exploit positive, adaptive way of solving problems (Paterson & et al., 2002). If the person feels safe he/she can perceive one and the same situation as a possibility to gain new experience. The person can be guided by not only a short-time goal but also the desire to transform the situation into a long lasting positive experience. In this case the individual will be able to fix his problems but not avoid them. The security conditions mean readiness to accept consequences of one’s own behaviour as well as the possibility to rely on somebody else.

The perception and assessment of security and the state of security are psychological processes; hence, they are subject to individual and group differences (Bar-Tal, 1991). Individual differences in perception and the state of security occur due to people’ diversity in their experience, ability to perceive, selectivity of perception, individual mode of processing information which effect interrelations of the perceived information and the ability to cope with threats (Bar-Tal et al., 1997; Epstein, 1994; Fiske &Taylor, 1991; Kruglanski, 1989; Lazarus et al., 1985; Nisbett & Ross, 1980). These differences imply that people evaluate the degree of danger in a different way on the one hand, on the other – their own and the group they belong to capabilities to overcome difficulties and cope with them (Bar-Tal et al., 1995). So, one may assume that security perceptions of adolescents and adults vary significantly.

Security perceptions are shaped individually and represent a subjective reflection of reality. Also, the category of security perceptions involves a great deal of other factors relating to conditions which can weaken or bolster security and its consequences. «Guided by his individual safety conception a person, trying to envisage events, builds up his behaviour, assesses the outcome of his actions, and alters the ways to interpret the world around him» (Zinchenko & Zotova, 2013. P. 111).

Security perceptions form on the basis of interacting information received from the environment and personal features. So, the sensation of the individual’ security is defined not only by his demographic, socio-economic characteristics and personal experience but also by psychological peculiarities associated with his age. «More or less adequate situational images appear depending on the situation uncertainties; these images determine the orientation system and the line of behaviour» (Dontsov & Perelygina, 2016. P. 69).

Psychologists consider the age of adolescence as the second most important stage following early childhood in personality development which includes both enormous opportunities and great menaces. This is a period of biological, cognitive and social changes. The teenager’ psychological security is a necessary condition for the continuous growth and development enhancing his maturity, independence and self-sufficiency. A number of researchers have attempted to explore the impact of age on security perception of adolescents. It is found that older teenagers feel more secure than younger ones (Bowen & Bowen, 1999; St. George & Thomas, 1997). The thing is that in the course of growing-up, teenagers form a more differentiated picture of the world (Harter, 1990; Marsh, 1989; Moretti & Higgins, 1999), and cognitive shifts that occur during adolescence lead to a specific form of “egocentrism” when the teenager’s conviction in his uniqueness is combined with confidence in his/her being the cynosure of all eyes.

The ability to assess risks is an important element of the state of security. In adults’ opinion, teenagers, as a rule, cannot evaluate risks adequately. Beyth-Marom and his colleagues (Beyth-Marom et al., 1993) revealed that teenagers perceive risk for themselves to a much lesser extent than their parents. The difference in perceiving risky actions by teenagers and adults is associated with the fact that adults evaluate risks for another person, and these estimations are typically higher than these for personal risks (Weinstein, 1980; Weinstein, 1983; Weinstein, 1984; Whalen et al., 1994).

Problem Statement

Despite recent extensive research on security issues the specifics of teenagers’ perception of security as a condition for personality development have not been dealt with so far.

Research Questions

-

Do teenagers’ assessment of individual security differ from adults’ evaluation?

-

Have teenagers any specific features of their perceptions about the state of their “self” in danger/security situations?

Purpose of the Study

This study aims at identifying the specificity of adolescents’ security perceptions. The fulfillment of this purpose implies that the following tasks should be solved: 1. To match the estimates of personal security of teenagers and adults; 2. To examine teenagers’ estimates in the categories “Me in danger” and “Me secure”.

Research Methods

Subjects

The sampling selected in line with the study goal consisted of two groups of respondents. The first group represented 147 schoolers from Yekaterinburg secondary schools aged 14-15 (average age=14.69), which corresponded to the G. Craig’s and D. Baucum’s periodization of adolescence (Craig & Baucum, 1998). There were 79 females and 68 males in this group.

The second group was a control group and consisted of 184 respondents aged 25-40, which was in line with early adulthood according to G. Craig and D. Baucum (Craig & Baucum, 1998). The group was equalized in terms of sex and education.

Measures and tools

In order to explore the teenagers’ security perceptions, the semantic differential method for researching the constructs of consciousness was used. We chose D. Peabody methodology which the labelled “4-pole model of personality trait” modified by A.G. Shmelyov as our instrument (Shmelyov, 2002). The objects of assessment were the following states: “Me now”, “Me in the past”, “Me in the future”, “Me in danger” and “Me secure”.

The results obtained were analyzed with the help of multidimensional scaling ALSCAL and exploratory factor analysis. The data were processed and analyzed via SPSS 20.0.

Findings

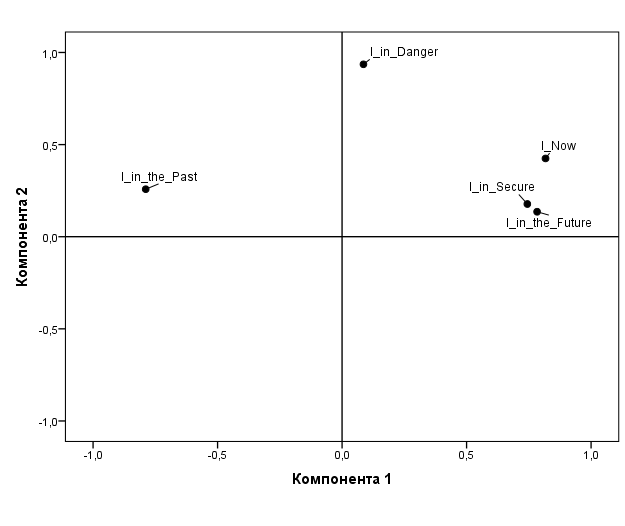

The application of multidimensional scaling allows us to construct a diagram reflecting mutual arrangement of the following categories “Me now”, “Me in the past”, “Me in the future”, “Me in danger” and “Me secure” in the teenagers’ consciousness.

So, the state “Me now” relates, to a greater extent, to the state “Me secure” than to the state “Me in danger”. The safest category for the teenagers is their future: the distance between these categories is minimal.

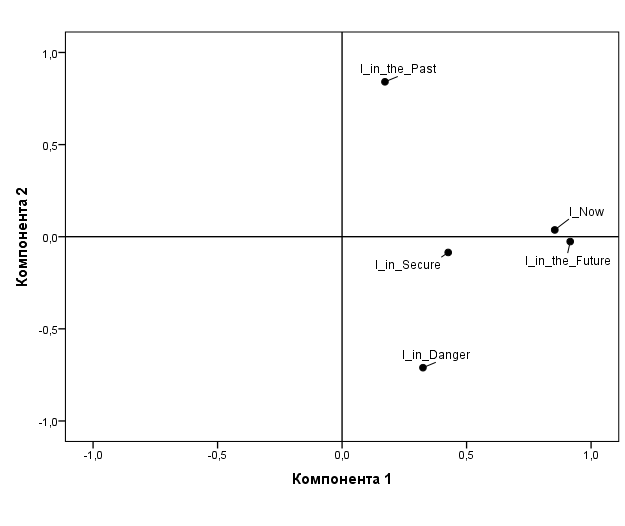

The results of the adults’ group of the sample show a different proportion of these categories. The closest states are “Me now” and “Me in the future”, i.e. unlike the teenagers, the respondents do not expect significant changes in their “self”. They also feel less secure than the teenagers and do not count on any changes in their state of security in the future.

To examine foundations according to which the teenagers allocate the categories in question in their consciousness the factor analysis was carried out resulting in identifying 4 significant factors.

Factor analysis of the adults’ group (25-40 aged) data also reveals 4 factors of significance.

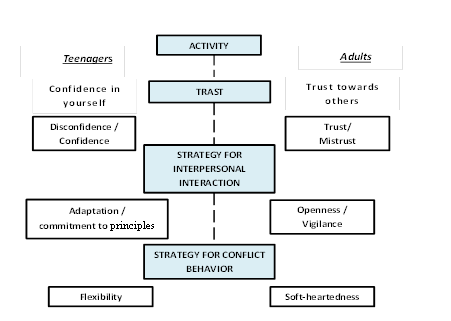

The comparative analysis of the data obtained makes it possible to conclude that these two groups have common foundations for differentiating danger/security situations, the present, the past and the future. These foundations include Activity, Trust, Strategy for Interpersonal Interaction and Strategy for Conflict Behaviour. The given foundations have specific features for the two groups under study.

Thus, the both groups under study have similar factor structure which shape perceptions of the categories “Me in danger” and “Me secure” but at that the content of these structural elements is different.

Conclusion

The study has revealed that the teenagers feel more secure than the respondents of the comparison group (aged 25-40). In addition, the adolescents expect their future to be even more secure.

While differentiating danger/security situations the teenagers resort to the same factor structure as the respondents aged 25-40. However, the very processes of the situation assessment and the choice of behaviour pattern differ. Accordingly, different features of perceiving the state of their “self” in danger/security situations form in these two groups.

The older group (aged 25-40) representatives investigate the environment while analyzing the situation, and on this basis they take a decision to use a proper strategy for interaction and behaviour in time of conflict. The teenagers when facing the situation evaluate, in the first place, how confidently/hesitantly they can function. Coming across the situation with a low risk of negative consequences or quite familiar one the teenagers regain confidence, then exhibit activity and adjust to the people around and social requirements (in a word, demonstrate their being socialized). Facing the situation when they find themselves uncertain, i.e. which is characterized by a high risk of negative outcome and unfamiliar one the adolescents do not spend their resources on adjustment (trying to learn the requirements, master the proper pattern of behaviour). Instead, they exhibit passivity and resort to their own constructs demonstrating commitment to principles. According to the results obtained the situation triggering the teenager’s uncertainty is assessed by the adolescents as a dangerous one.

Therefore, the data obtained underline the necessity to devise a special training aimed at preparing the teenagers for secure interaction with dangerous situations since in the course of teenagers’ vital activity the experience of dealing with dangerous situations is accumulated spontaneously, and it does not provide the formation of their self-confidence in case of facing dangers and threats. Such a preparation should involve models of acting in dangerous situations. The existing practice concentrates on behavioural safety but not on behaviour in the situations inducing gangers, which is confirmed by the high rate of children injury and the great number of children’s loss in dangerous everyday situations. It is noteworthy that prospects for further research in this field reside in examining a range of situations which teenagers perceive as highly dangerous.

Acknowledgments

The authors of the article express their sincere gratitude to The Russian Science Foundation for funding, grant # 16-18-00032.

References

- Bar-Tal, D. (1991). Contents and origins of the Israelis' beliefs about security. International Journal of Group Tensions, 21, 237-276.

- Bar-Tal, D., Jacobson, D. & Freund, T. (1995). Security feelings among Jewish settlers in the occupied territories: A study of communal and personal antecedents. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 39, 353-377.

- Bar-Tal, Y., Kishon-Rabin, L. & Tabak, N. (1997). The effect of need and ability to achieve cognitive structuring on cognitive structuring. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 73(6), 1158-1176.

- Beyth-Marom, R., Austin, L., Fischhoff, B., Palmgren, C. & Jacobs-Quadrel, M. (1993). Perceived consequences of risky behaviours: Adults and adolescents. Developmental Psychology, 29(3), 549-563.

- Bowan, N. & Bowan, G. (1999). Effects of crime and violence in neighborhoods and schools on the school behaviour and performance of adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Research, 14, 319-342.

- Craig, G. J. & Baucum, D. (1998). Human Development. NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Dontsov, A. I. & Perelygina, E. B. (2016). The Trust Factor for Children in a Risk Situation. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 233, 68-72.

- Epstein, S. (1994). Integration of the cognitive and psycho-dynamic unconscious. American Psychologist, 49, 709-724.

- Fiske, S. T. & Taylor, S. E. (1991). Social cognition. NY: McGraw-Hill.

- Harter, S. (1990). Self and identity development. In Feldman S. S., Elliott G. R. (Eds.). At The Threshold: The Developing Adolescent (pp. 352-387.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Helson, R. & Wink, P. (1987). Two conceptions of maturity examined in the findings of a longitudinal study. Personality processes and individual differences. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 531-541.

- Kruglanski, A. W. (1989). Lay epistemics and human knowledge: Cognitive and motivational bases. NY: Plenum.

- Lazarus, R., Delongis, A., Folkman, S. & Gruen, R. (1985). Stress and adaptational outcomes. American Psychologist, 40, 770-779.

- Little, M. & Kobak, R. (2003). Emotional security with teachers and children's stress reactivity: A comparison of special-education and regular-education classrooms. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 32, 127-138.

- Marsh, H. W. (1989). Age and sex effects in multiple dimensions of self-concept: Preadolescence to early adulthood. Journal of Educational Psychology, 81, 417-430.

- Moretti, M. M. & Higgins, E. T. (1999). Internal representations of others in self-regulation: A new look at a classic issue. Social Cognition, 17, 186-208.

- Nisbett, R. & Ross, L. (1980). Human inference: Strategies and shortcomings of social judgment. NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Paterson, M., Green, J. M., Basson, C. & Ross, F. (2002) Probability of assertive behaviour, interpersonal anxiety and self-efficacy of South African registered dietitians. Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics, 15, 9-17.

- Scheider, B. H., Atkinson, L. & Tardif, C. (2001). Child-parent attachment and children's peer relations: A quantitative review. Developmental Psychology, 37, 86-100.

- Shmelyov A.G. (2002). Psychodiagnostics of Personal Traits. St.-Petersburg: Rech’. [in Russian].

- St. George, D. & Thomas, S. (1997). Perceived risk of fighting and actual fighting behaviour among middle school students. Journal of School Health, 67, 178-181.

- Suess, G. J., Grossmann, K. E. & Sroufe, L.A. (1992). Effects of infant attachment to mother and father on quality of adaptation in preschool: From dyadic to individual organization of self. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 15, 43-66.

- Van der Mark, I. L., van Ibzendoorn, M. H. & Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J. (2002). Development of empathy in girls during the second year of life: Associations with parenting, attachment, and temperament. Social Development, 11, 451-468.

- Weinstein, N. (1980). Unrealistic optimism about future life events. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(5), 806-820.

- Weinstein, N. D. (1983). Reducing unrealistic optimism about illness susceptibility. Health Psychology, 2(1), 11-20.

- Weinstein, N. D. (1984). Why it won't happen to me: Perceptions of risk factors and susceptibility. Health Psychology, 3(5), 431-457.

- Whalen, C. K., Henker, B., O'Neil, R., Hollingshead, J., Holman, A. & Moore, B. (1994). Optimism in children's judgments of health and environmental risks. Health Psychology, 13(4), 319-325.

- Zimmerman, P., Maier, M. A., Winter, M. & Grossman, K. E. (2001). Attachment and adolescents' emotion regulation during a joint problem-solving task with a friend. International Journal of Behavioural Development, 25, 331-343.

- Zinchenko, Y. P. & Zotova, O. Y. (2013). Social-psychological Peculiarities of Attitude to Self-image with Individuals Striving for Danger. Procedia – Social and Behavioural Sciences, 86, 110-115.

- Zotova, O. Yu. (2011). Personality Security as a Socio-Psychological phenomenon. Yekaterinburg: Liberal Arts University-University for humanities. [in Russian].

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

13 July 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-042-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

43

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-694

Subjects

Child psychology, developmental psychology, child care, child upbringing, family psychology

Cite this article as:

Zotova, O. Y., & Tarasova, L. V. (2018). Features Of Teenagers Perceptions Of Security. In S. Sheridan, & N. Veraksa (Eds.), Early Childhood Care and Education, vol 43. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 230-238). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.07.31