Abstract

Business incubators have now been recognized as effective tools in providing business assistance to start-up firms. In both developed and developing countries, the number of incubators are growing tremendously. As the birth rate of incubators increases, so do its challenges. Malaysia, as one of the developing countries in the Asian continent, has also established a number of business incubators to breed and foster the growth and survival of start-up firms. Thus, this study discusses the incubation model applied in Malaysia and the challenges faced by these incubators using secondary data including policies, previous literatures and reports related to Malaysian incubators. The findings of this study call the government to rethink the key role of incubator managers and staffs, internal structure of the incubator concept and process, intellectual properties management, strategic alliances with universities-industries and financial assistance in enhancing the support provided by the business incubators in Malaysia. The key challenges highlighted in this study signal important policy lessons for other developing countries that aim to create and map an effective business incubator ecosystem.

Keywords: Business incubatorsincubation challengesfunding supportincubator managersinternal structurestart-up firms

Introduction

Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) has widely been recognized to play a surprisingly critical role in creating jobs and stimulating the growth of an economy (Paul, Parthasarathy, & Gupta, 2017). Despite of the significant contribution of SMEs to the economy, in the practical perspective, critical challenges and difficulties which lead to high failure rate in the business still lie ahead (Paul et al., 2017; Rasmussen, Mosey, & Wright, 2014). Literature has indicated that 53 percent of SMEs fail within their first three years of operation (Mason, 2014). Specifically, 9 out of 10 start-ups have failed (Patel, 2015). This indicates that the start-ups indisputably face great challenges particularly due to their liabilities of newness and smallness in the industry (Chandra, Chao, & Astolpho, 2014).

Malaysia, a developing country in the Asian continent, has been making a significant progress in its economic development over the past two decades. In this country, SMEs have been recognized as the backbone of its economy (Umrani, Johl, & Ibrahim, 2017) whereby in 2011, SMEs accounted 97.3 percent of total establishments in Malaysia (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2011). The figure explains 645,136 SMEs compared to 17,803 large firms (Department of Statistics Malaysia, 2011). Out of 645,136 SMEs 77 percent (496,458 firms) are micro enterprises. These micro enterprises can be categorized as start-up firms as they only employ less than 5 full-time employees. This statistic draws attention that start-ups contribution is crucial for the Malaysian economy.

However, despite various government supports, programs, and funding targeting the SMEs by government agencies such as Small and Medium Enterprise Corporation Malaysia (SME Corp Malaysia) and Malaysia External Trade Development Corporation (MATRADE), the failure rate is still high. As reported by seminal works on SMEs in Malaysia, the failure rate among these establishments was at 60 percent (Ahmad & Seet, 2009; Chong, 2012; Khalique et al., 2011). Therefore, as one of the efforts to escalate success rate and survival of SMEs, business incubator programs have been adopted (SMIDEC, 2007). Interestingly, 67 percent of public owned incubation centers in Malaysia are heavily subsidized. This shows that in ensuring the success of start-up creation, the start-up firms have to rely heavily on government support.

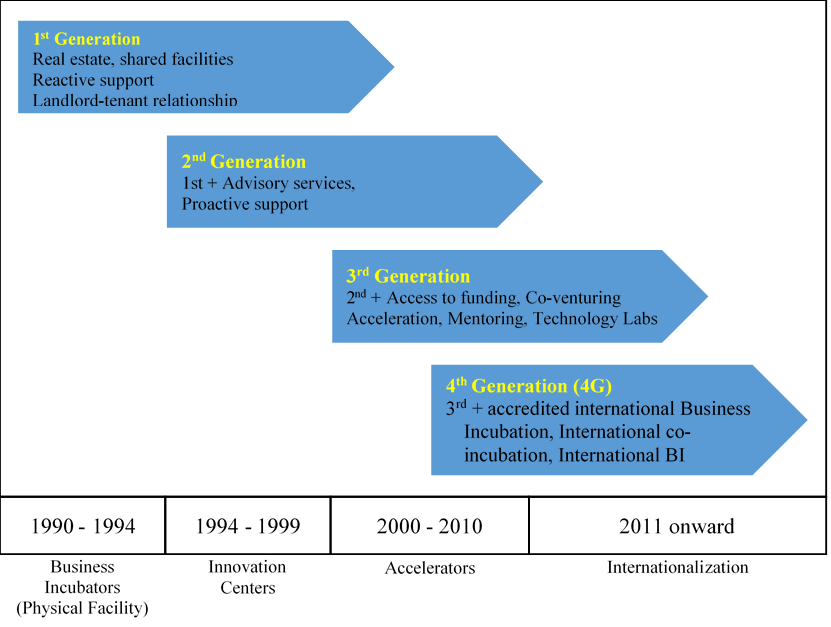

Over the last two decades, the Malaysian government has been initiating many incubation centers merely to promote and fulfil the underlying needs for start-up firms. In the 2017 Malaysian budget, the year 2017 was declared as Start-up and SME Promotion Year (Business Insider Malaysia, 2017). Although the government plays a vital role and catalyst for facilitating and fostering the development of incubation programs in Malaysia, the service provided by the business incubators is still at lower level. A key finding from the literature identifies that 68 percent of the business incubators in Malaysia are still in the first and second generation models, whereby at these stages, the business incubators only provide shared physical facilities and advisory services to their respective incubated firms. The Malaysian incubators, at this stage, are lack of support from the management of which its availability is generally on request (SME Corp, 2012). Therefore, this study aims to discuss the emerging challenges faced by business incubators in Malaysia. These challenges, if not wisely tackled, will cause hiccups in incubation process and distort its ability to provide core value proposition in the globalization world.

Definition of Incubator

Business incubator has become one of the most widely utilized tools to foster the development of start-up firms in early stages. According to the European Commission (2002), business incubator is an institution that provides entrepreneurs with a conductive business environment to assist them in establishing and developing their business. By providing a 'one-stop’ service, it enables a reduction in the overhead costs by sharing facilities and improves the survival and growth prospects of start-ups and small firms at the early stage of business development. The services provided by an incubator can be classified into five types which are (1) physical infrastructure, (2) office support services, (3) access to financial supports, (4) process support, and (5) access to network (Pauwels, Clarysse, Wright, & Van Hove, 2016). Taking into account the evolution (Bruneel, Ratinho, Clarysse, & Groen, 2012) and heterogeneity (Barbero, Mike, Alicia, & Garcia, 2014) of business incubation models over time, Table

Incubation Model in Malaysia

In order to understand and access the impact of business incubators on incubated firms, recent researches viewed the value proposition offered by the incubators in generational terms and has been spanning over decades ( Bruneel, Ratinho, Clarysse, & Groen, 2012; infoDev/The World Bank, 2014; Theodorakopoulos & Kakabadse, 2014). However, as there are differences in economic, social, cultural and environmental areas, no one standard fit model can be applied to all incubators (Machado, Silva, Borba, & Catapan, 2015).

In line with this reason, Malaysian incubation models have undergone several evolution movements over the years. Basically, they are classified into four generations based on the period of change (SME Corp, 2012). Figure

Source: SME Corp (2012)

Role of Incubation in Malaysia

Besides transforming the Malaysian economy into a knowledge-based economy, business incubators programs has also been seen to shed light to the SMEs as they provide a nurturing business environment to accelerate the development of entrepreneurs. (Indiran, Khalifah, Ismail, & Ramanathan, 2017; InfoDev, 2010; Jusoh, 2006). Among the roles played by the Malaysian incubators are to create wealth and contribute to economic development by generating employment, comemercializing new product or process to the market, encouraging research and development activities, link with universities and research institutes, support for development of start-ups (Jamil et al., 2016), help entrepreneurs to start or expand their business, increase survival rate of entrepreneurs (SME Corp, 2012), strengthen collaboration and facilitate technology transfer (Ong & Hassani, 2011) and innovation (InfoDev, 2010) and commercerlize ideas and university research with spin-off companies (Indiran et al., 2017).

As the roles of an incubator are vital, Malaysia has groomed a considerable number of incubator centers. According to the Technology Park Malaysia (TPM), there were 113 active business incubators in Malaysia in 2015 of which 95 of them were government-funded and 18 were public- funded incubators. A report by SME Corp in 2012 has outlined a realistic indication of Malaysia incubation scenario that 68 percent of business incubators in Malaysia are in the first (20%) and second (48%) generations. Meanwhile, 29 percent of business incubators are in the third generation and only 3 percent fall in the fourth generation (Table

Problem Statement

Although given task to develop and nurture the SMEs, business incubators often lack adequate competence to contribute positively to the development of SMEs. Previous studies have addressed the challenges faced by business incubators in developing countries such as client acquisition and SMEs enrolled, inefficient management, support structures, rarely self-sufficient, lack of technological facility and limited entrepreneurial skills (Lose & Tengeh, 2015). Aligned with the foregoing challenges, the business incubators are having difficulties in order to create a conducive ecosystem, regardless of countries and context, which may ultimately effect the performance of business incubation. Even though, there are relatively high investment on incubator programs by the government and private institution, there are lack of empirical evidence on the impact of business incubator programs on the SMEs, particularly in Malaysia (Abdul Khalid, Gilbert, & Huq, 2012). In addition, there are limited studies on the challenges faced by incubators. As such, this study is conducted to explain the challenges lay ahead of the business incubators in Malaysia.

Research Questions

There are two objectives of this study:

to provide an overview of business incubation in Malaysia, and

to identify the challenges faced by business incubators in Malaysia.

Purpose of the Study

The main purpose of this study is to identify the challenges faced by business incubators in Malaysia. However, in order to have a better understanding, this study, first, reviewed an overview of business incubation, followed by the models and role incubators in Malaysia. Thus, findings of this study classify the challenges into four aspects; (i) human capability, (ii) support structure, (iii) access to network, and finally (iv) access to funding, which can be associated ultimately to the performance of business incubation.

Research Methods

This study searched a relevant previous literature on the challenges of business incubation in Malaysia particularly, regardless of managerial, operational, or financial aspect. The search includes the online and offline materials using secondary data such as policies, previous literatures and reports related to Malaysian incubators;

Findings

Despite the growing interest in incubation programs and the benefits gained by the incubated firms, the challenges faced by the incubators are numerous, particularly in developing countries (Lose & Tengeh, 2015). Malaysia now, is moving forward from an innovation-based to a knowledge-based economy whereby its focus is in line with the objectives of SME Masterplan 2012-2020. Business incubator programs has been identified by the government as a strategy to generate greater impact to SME development. Thus, tremendous support has been given by the government including a huge number of financial assistance allocated to incubator programs (SME Corp, 2012). Yet, there are many challenges faced in the process of incubation in Malaysia.

Lack of Human Capability

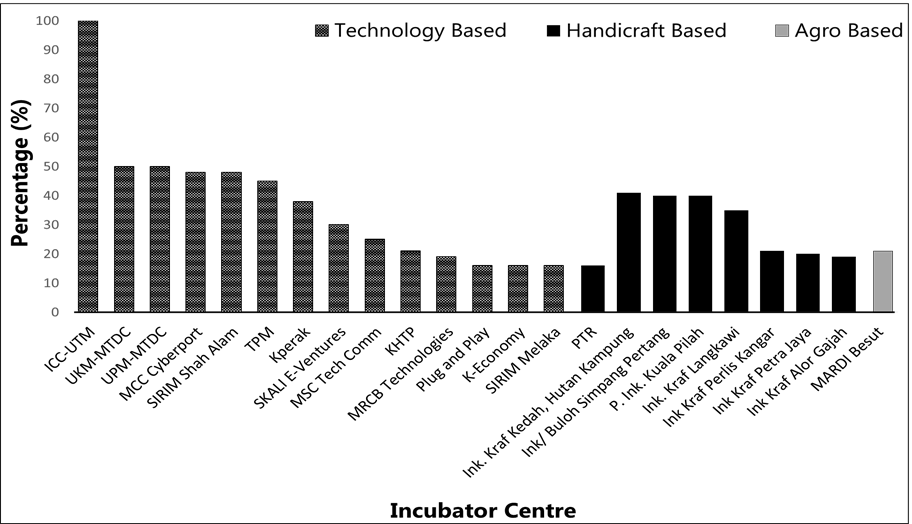

The major challenge in most of business incubators established in Malaysia is poor management (Chandran, 2010; Ong & Hassani, 2011; Jusoh, 2006). Besides, lack of adequate skilled workforce of incubator managers and the incubator management team is also another key challenge (Mohd Saffar, 2007; Ong & Hassani, 2011; Jusoh, 2006). In some cases, the incubators are managed by a bureaucrat who has poor entrepreneurship knowledge and mindset (Mohd Saffar, 2007; Jusoh, 2006). This situation leads to low connection with community and industry network. Incubator managers are the agents that connect the incubated firms with the external business world. They are the soul for the incubator. Therefore, the qualification of incubator managers is the key that unlocks the door to the success of business incubators (Lose & Tengeh, 2015). The SME Corp (2012) reported that most of the incubator middle managers are bachelor degree holders, while only three of the top managers are certified incubator managers. They do not have value proposition related to incubator programs such as certified coach. In other words, there is a lack of skilled staff to coach and monitor the incubated firms. This phenomenon is like ‘the blind leading the blind’ system (Ong & Hassani, 2011). As a result, the incubated firms are most likely to neither launch a new successful business nor to sustain in the market (Mohd Saffar, 2007). In much worse scenario, many of the incubated firms started to move out (Jusoh, 2006). However, business incubators that are of the third generation and above (generally technology based) are found to have more highly qualified incubator managers (Masters and Ph.D. graduates) to provide the necessary advisory support services to the incubated firms (Figure

Source: SME Corp (2012)

Lack of Internal Structure

Another major gap among incubators in Malaysia is that they lack internal structured incubation programs. According to SME Corp. (2012), 90 percent of the incubators do not have structured program. Only a few of them are run based on a well-structured program following infoDev’s module that includes research, capacity building and business advisory services (SME Corp, 2012). Mohd Saffar (2007) has pointed out that there are no standard definition and concept of business incubation modeled in Malaysia. Besides, business incubators in Malaysia have been seen as having weak underlying incubation processes where most of the incubators do not have clear selection criteria (Abdul Khalid et al., 2014). However, the technology driven incubation in Malaysia has more comprehensive entry criteria which could increase their capability of product commercialization. The entry criteria used by them are the potential of commercialization, revenue and profit making potential, innovative product and service and also the alignment of the objective of the incubator and incubated firms (SME Corp, 2012).

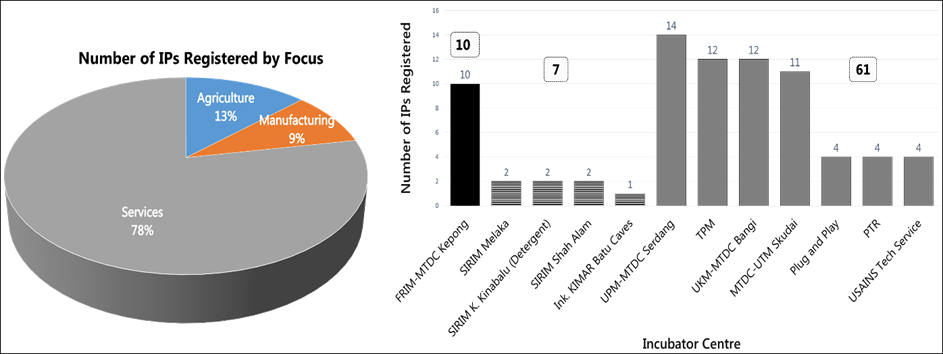

Furthermore, support on the intellectual property (IP) rights is very important in incubation center (Chandran, 2010). Another drawback of Malaysian incubators is that only 78 IPs are registered since 2000 till 2012 (Figure

Limited Access to External Networks

Another challenge is low strategic alliances between other stakeholders such as customers, suppliers, research institutions, university and industry. This can be one of the key reasons for low number of IPs. Furthermore, the link with private sectors is also low (Said, Adham, & Abdullah, 2012). According to Said et al. (2012), this incubator-private sector link is crucial as its absence will disturb the clustering effect within an area.

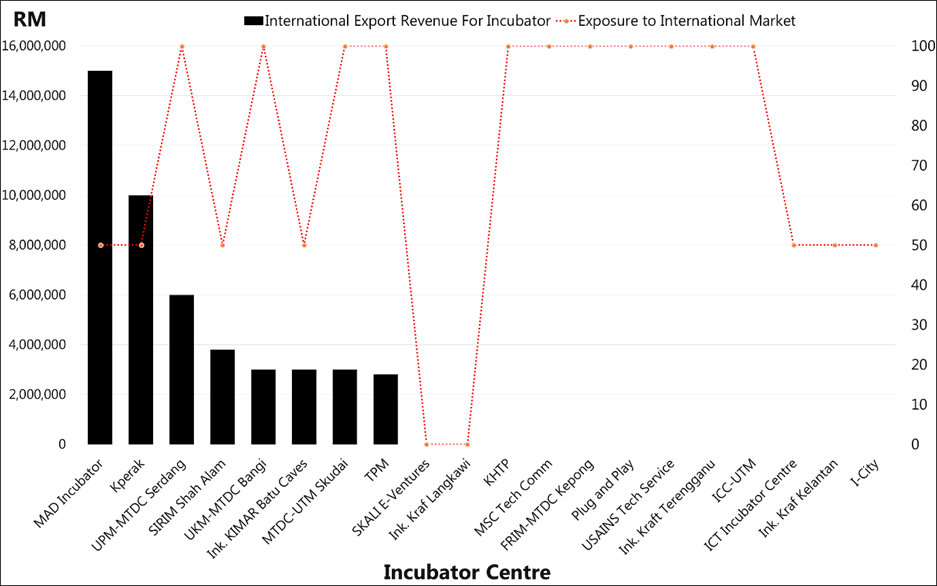

One of the reasons for poor collaboration between the incubators and their stakeholders is the location of the incubation centers. A report by SME Corp (2012) highlighted that only high-tech and Information, Communication and Technology (ICT) incubators are located within structured ecosystem such as technology parks, universities and research institute. As such, these incubators have the ability to provide strong customer supports. In addition, for the majority of the incubation centers, international marketing is not their top priority. As depicted in Figure

Access to Funding and Investment

It is not deniable that huge financial aid has been allocated for incubation programs in Malaysia. However, considering the large number of business incubators in this country, the amount allocated is still insufficient. Financial support is one of the most critical sources that is highly needed by a firm particularly at the very early stage of its development (Lose & Tengeh, 2015). However, more than 50 percent of the business incubators do not provide incubated fims with any internal financial funding. As they are infants, the incubated firms would undoubtedly face great challenges in sourcing funding at their own effort. Therefore, to overcome this obstacle, the government has established a number of funding including grants, venture capital funds and also soft loans (SME Corp, 2012). However, the funds have not been disbursed accordingly (Mohd Saffar, 2007; Ong & Hassani, 2011; Jusoh, 2006). This is due to, first, the business incubators in Malaysia are parked in various ministry (Mohd Saffar, 2007) such as Ministry of International Trade and Industry (MITI), Ministry of Agriculture (MOA), Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation (MOSTI), Ministry of Tourism and Culture (MOTAC), Ministry of Higher Education (MOHE), Ministry of Rural and Regional Development (KKLW), and Ministry of Industrial Development Sarawak (MID Sarawak). Thus, lack of co-ordination among ministries leads to duplication of task and waste of resources. For example, a duplication is obvious when most of the technology business incubators are located in Klang Valley, near Kuala Lumpur. Second, it is due to difficult bureaucratic measures or due to grants being issued to technology companies which employ ‘know-who’ rather than ‘know how’ (Jusoh, 2006). In addition, Malaysia is facing with limited venture capitalists and angel investors who are willing to invest in the incubated firms (Chandran, 2010). A possible explanation for this is because of the product immaturity in the market or the absence of products’ IP rights. Therefore, the government has to set forth grant funding criteria, either based to sector-focus or recipient-focus, besides reducing the bureaucratic obstacles in each agency. Apart from that, the government also has to give prior effort to strategize the coordination between agencies and ministries at federal level to avoid duplication of tasks, be more transparent and avoid bureaucratic procedures. The government could also build a national innovation hub as a responsible independent entity to take appropriate actions in filling these gaps.

The key challenges of business incubators in Malaysia can be summarised as in Table

Conclusion

This study provides a view regarding the challenges faced by Malaysian business incubators from a different angle ranged from the nearest degree such as human capability of incubator, followed by the challenges in the process of incubation internal processes to the furthest degree such as external network. The finding calls for the government to take few caution steps. Firstly, the government has to enhance the role of incubator managers and team by providing more training and exposure on incubator management as well as on recruiting competent staffs to be a part of the team. Secondly, the government has to strengthen the system and process by having a standard incubation definition and concept, improving IP management and increasing R&D activities. Finally, the government has to increase strategic alliances among incubators and university, industry and other professional board through effective communication and international linkages. The key barriers highlighted in this paper should be important policy lessons for any developing country that aims to improve its incubators’ success. However, this study neglects to unfold and discuss on incubated firms’ challenges, which are hoped to be covered in future research. Stemming from this finding, the researcher of this study is exploring on how these challenges can be tamed by using intellectual capital model and thus recommed future research to exploit the notion ‘intellectual capital’ in business incubators-incubation context by providing empirical evidence.

References

- Abdul Khalid, F., Gilbert, D., & Huq, A. (2012). Investigating the underlying components in business incubation process in Malaysian ICT incubators. Asian Journal of Social Sciences & Humanities Configurations, 1(1), 88–102.

- Abdul Khalid, F., Gilbert, D., & Huq, A. (2014). The Way Forward For Business Incubation Process in ICT Incubators in Malaysia. International Journal of Business and Society, 15(3), pp. 395–412.

- Ahmad, N. H., & Seet, P. (2009). Dissecting Behaviours Associated with Business Failure: A Qualitative Study of SME Owners in Malaysia and Australia. Asian Social Science, 5(9), pp. 98–104.

- Barbero, J. L., Mike, C. C., Alicia, W., & Garcia, R. (2014). Do different types of incubators produce different types of innovations?, pp. 151–168.

- Bruneel, J., Ratinho, T., Clarysse, B., & Groen, A. (2012). The evolution of Business incubators: Comparing demand and supply of business incubation services across different incubator generations. Technovation, 32(2), pp. 110–121.

- Business Insider Malaysia (2017). What’s the future of the startup ecosystem in Malaysia?http://www.businessinsider.my/iknewit-the-future-of-the-startup-ecosystem-in-malaysia/3/#bvGIPCu6EXoR9E63.99http://www.businessinsider.my/iknewit-the-future-of-the-startup-ecosystem-in-malaysia/3/#Ei8y6KiV5MCEtTHR.97

- Chandra, A., Chao, C.-A., & Astolpho, E. C. (2014). Business incubators in Brazil: does affiliation matter? International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Small Business, 23(4), pp. 436–455.

- Chandran, V. G. R. (2010). R&D commercialization challenges for developing countries The case of Malaysia. TECH MONITOR, (Nov-Dec 2010), pp. 25–30.

- Chong, W. Y. (2012). Critical Success Factors for Small and Medium Enterprises : Perceptions of Entrepreneurs in Urban Malaysia, 7(4), pp. 204–215.

- Department of Statistic Malaysia. (2011). Economic Census 2011: Profile of SMEs. Malaysia.

- European Commission. (2002). Final report: benchmarking of Business Incubators. European Commission Enterprise DirectorateGeneral (Vol. 51). Retrieved from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20657521

- Indiran, L., Khalifah, Z., Ismail, K., & Ramanathan, S. (2017). Business Incubation in Malaysia: An Overview of Multimedia Super Corridor, Small and Medium Enterprises, and Incubators in Malaysia. In Handbook of Research on Small and Medium Enterprises in Developing Countries, IGI Global, pp. 322–344.

- Indiran, L., Khalifah, Z., Ismail, K., Rasli, A., & Jamil, A. A. (2017). Case Study: The influence of Intellectual Capital of UTM Sprinter Incubator Centre (UTMSprinterTM), Universiti Teknologi Malaysia, Malaysia. In Innovative Youth Incubator Awards 2017; An Anthology of Case Study, Academic Conferences and Publishing International limited, Reading, U.K., pp. 29-52.

- InfoDev. (2010). Global Good Practice in Incubation Policy Development and Implementation. The International Bank for Reconstruction and Development / The World Bank. Retrieved from http://www.infodev.org/infodev-files/resource/InfodevDocuments_834.pdf

- infoDev/The World Bank. (2014). Reaching Entrepreneurs through Alternate Models: Lessons from Virtual Incubation Pilots. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- Jamil, F., Ismail, K., Siddique, M., Khan, M. M., Kazi, A. G., & Qureshi, M. I. (2016). Business Incubators in Asian Developing Countries. International Review of Management and Marketing, 6(4S), pp. 291–295.

- Jusoh, S. (2006). Incubators As Catalysts in Developing High Technology Businesses : Malaysia ’ S Experience. ATDF Journal Volume, 3(1), pp. 25–29.

- Khalique, M., Abdul, J., Shaari, N., Ageel, A., Isa, A. H. M., Shaari, J. A. N., & Ageel, A. (2011). Challenges faced by the Small and Medium Enterprises (SMEs) in Malaysia: An Intellectual Capital Perspective. International Journal of Current Research, 3(2010), pp. 398–401.

- Lose, T., & Tengeh, R. (2015). The Sustainability and Challenges of Business Incubators in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Sustainability, 7(10), pp. 14344–14357.

- Machado, A. de B., Silva, A. R. L. da, Borba, M. L., & Catapan, A. H. (2015). Innovation Habitat: Sustainable possibilities for the society. International Journal of Innovation, 3(2), 67–75.

- Mason, K.M. (2014). Research on small businesses. Small business statistics. Retrieved from: http://www.moyak.com/papers/small-business-statistics.html

- Mohd Saffar, A. (2007). Asia Regional Workshop Innovation : The Role of Business Incubation Innovation and Entrepreneurship Policy Framework : The Malaysian Experience in Building Sustainable Incubation Industry (Movement). Forum American Bar Association.

- Nicholas Theodorakopoulos, Nada K. Kakabadse, C. M. (2014). What Matters in Business Incubation ? A Literature Review and a Suggestion for Situated Theorising, pp. 1–31.

- Ong, S., & Hassani, S. (2011). Final Repor: An assessment of the influence of incubators on the entrepreneurship environment for innovators in Malaysia, (June), pp. 1–84.

- Patel, N. (January 16, 2015). Forbes. 90% of startups fail: Here is what you need to know about the 10%. https://www.forbes.com/sites/neilpatel/2015/01/16/90-of-startups-will-fail-heres-what-you-need-to-know-about-the-10/#4993fbcc6679

- Paul, J., Parthasarathy, S., & Gupta, P. (2017). Exporting challenges of SMEs : A review and future research agenda. Journal of World Business, 52(3), pp. 327–342.

- Pauwels, C., Clarysse, B., Wright, M., & Van Hove, J. (2016). Understanding a new generation incubation model: The accelerator. Technovation, 50–51(2010), pp. 13–24.

- Rasmussen, E., Mosey, S., & Wright, M. (2014). The influence of university departments on the evolution of entrepreneurial competencies in spin-off ventures. Research Policy, 43(1), pp. 92–106.

- Said, M. F., Adham, K. A., & Abdullah, N. A. (2012). Incubators and Goverment Policy for Developing IT Industry and Region in Emerging Economies. Asian Academy of Management Journal, 17(1), pp. 65–96.

- SME Corp. (2012). Final Report “ Study on Enhancing the Effectiveness of Incubation Centres as a Support Mechanism for SME Development in Malaysia ” , December 2012.

- SMIDEC. (2007). Policies, Incentives, Programmes and Financial Assistance for SMEs. Malaysia.

- Technology Park Malaysia, TPM. (2015). Compilation of Incubution Data.

- Umrani, A. I., Johl, S. K., & Ibrahim, M. Y. (2017). Ownership Structure Attributes , Outside Board Members and SMEs Firm Performance with Mediating Effect of ... Ownership Structure Attributes , Outside Board Members and SMEs Firm Performance with Mediating Effect of Innovation in Malaysia, (April).

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 July 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-043-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

44

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-989

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues, industry, industrial studies

Cite this article as:

Indiran, L., Khalifah, Z., & Ismail, K. (2018). The Challenges Of Business Incubation: A Case Of Malaysian Incubators. In N. Nadiah Ahmad, N. Raida Abd Rahman, E. Esa, F. Hanim Abdul Rauf, & W. Farhah (Eds.), Interdisciplinary Sustainability Perspectives: Engaging Enviromental, Cultural, Economic and Social Concerns, vol 44. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 471-482). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.07.02.51