Abstract

An effective disclosure of corporate information has increasingly becoming more critical as the world market begins a long shift toward a higher share of market-based financing. In the future, IR is expected to play a bigger role in promoting understanding of interdependencies between various capitals that a company has and support integrated thinking, decision-making and actions that focus on the creation of value over the short, medium and long term. Motivated by the gap among prior IR related studies particularly the one conducted within Southeast Asian region, this study provides evidence, through content analysis, on the extent of IR information being reported by the top 60 (30 each) Malaysian and Singapore public listed companies. The evidence suggests that public listed companies in both countries have incorporated some elements of IR in their annual report with each country focuses on different elements of IR. Despite Singapore being a pioneer in IR within Southeast Asian region, the results show there is no significant difference between these two countries when it comes to the IR information presented in their companies’ reports.

Keywords: Integrated reportingMalaysiaSingaporecontent elementsguiding principles

Introduction

In recent decades, concerns have been raised on the adequacy of the traditional financial reporting practices in meeting various information needs of the stakeholders (Adams, Fries, & Simnet, 2011; Cohen, Holder-Webb, Nath, & Wood, 2012). As a result, new reporting requirements have continuously being introduced through a series of laws, regulations, standards, codes, guidelines and stock exchange listing requirements (Frías-Aceituno, Rodríguez-Ariza, & García-Sánchez, 2013). One significant outcome of these ongoing changes in the reporting requirement is the birth of nonfinancial reporting focusing specifically on the reporting of sustainability information. Sustainability reporting commonly referred as corporate social responsibility (CSR) reporting has evolved significantly with some companies have gone to the extent of producing a separate report on their CSR activities while others opted for only a section of their annual report. With the growing popularity of CSR report, the volume of disclosure related to non-financial information is expected to increase rapidly over the last decade and will continue to increase in the future (Aras & Crowther, 2009).

Unfortunately, many of these reports have disclosed disconnected information leading to disclosure gaps and confusion that eventually affects stakeholders’ decision-making (Frías-Aceituno et al., 2013). Criticism on the decision usefulness of sustainability data for investors including the inability of placing the data in the context of companies’ strategy and business model, the lack of a link to financial issues and the lack of materiality assessment of the different sustainability issues have been raised. To tackle these criticisms and as part of their efforts to meeting the needs of their stakeholders, some leading companies have started to combine all of their reports into a single report i.e. integrated report or IR (Eccles & Kruz, 2010). According to the International Integrated Reporting Council (IIRC), IR provides a broader explanation of performance, highlighting a company access to resources, its dependence on how they are used, the impact and their relationship with other forms of capital (IIRC, 2011, p8).

IIRC (2013, p. 7) defines IR as:

“A concise communication about how an organization’s strategy, governance, performance and prospects, in the context of its external environment, lead to the creation of value over the short, medium and long term”

It aims, among others, at promoting understanding of interdependencies between various capitals that a company has and support integrated thinking, decision-making and actions that focus on the creation of value over the short, medium and long term (IIRC, 2013).

IR is claimed as the latest innovation of reporting that raises new challenges to the companies as the information is expected to be tied closely to companies’ strategy and value creation process (Stubbs and Higgins, 2014). To ease the implementation of IR, IIRC, a global coalition of regulators, investors, companies, standard setters, the accounting profession and non-governmental organization responsible in establishing IR and thinking within mainstream business practice has developed an IR framework. IIRC is also creating networks around the world to help participating countries transform not only the way they report but also the way they think and act. At countries' level, South Africa is championing the road to the full implementation of IR by being the first country in the world to make it compulsory for its public listed companies to implement IR. With the establishment of Integrated Reporting Committee of South Africa in May 2010, King III report on Code of Governance Principles was released and consequently led to the requirement for all of South African public listed companies to issue an IR in the future (IIRC, 2013).

IR in Southeast Asian region is still very much in its infancy stage. Despite its infancy stage, several Southeast Asian countries have started their move towards IR. Malaysia, for example, have seen several of its top public listed companies expressing their intention of adopting IR. Even though the current stand of Malaysian stock exchange, Bursa Malaysia, is that IR will be market led, an Integrated Reporting Steering Committee (IRSC) was established within the Malaysian Institute of Accountants (MIA) on 18 December 2014 upon the recommendation of the Securities Commission of Malaysia. The Committee focuses on creating the awareness and promoting IR in Malaysia. While the implementation of IR will not be made mandatory, at least in the near future, the regulatory body of Malaysia has shown a positive attitude towards IR and will be more likely to continue its efforts in encouraging all Malaysian public listed companies to adopt it. With several top public listed companies in Malaysia have expressed their intention of adopting IR, it is expected that more companies will take serious efforts on this matter.

Another country that is currently active in promoting IR is Singapore. Within the setting of Southeast Asian region, Singapore is seen as the pioneer of IR as it is the only Southeast Asian country joining the Pilot Programme of IIRC. The country has also established the Institute of Singapore Chartered Accountants (ISCA) Integrated Reporting Steering Committee, or IRSC in short, in 2013 to raise awareness and understanding of IR as well as to play a leading role in influencing and shaping the development of the IR Framework in Singapore. At that time, the establishment of IRSC is the first of its kind in the region, making Singapore the leader in IR implementation in Southeast Asia region.

With this growing interest of IR in the Southeast Asia region, this present study aims to provide insights on the existence (or not) as well as potential gaps that exist in the current corporate report of top public listed companies, by market capitalization, in Malaysia and Singapore. Two sets of IR checklist, representing the content element and guidance principle of IR has been constructed based on the IIRC’s framework and is used to identify the existence of IR related element in the annual reports of Malaysian and Singapore public listed companies.

Problem Statement

The establishment of IRSC within both Malaysian and Singapore setting indicates a substantial support from their regulators and professional bodies. This is no surprise given that the world has started to shift towards a higher share of market-based financing and it is the role of regulators to protect the interest of all stakeholders involve. The legitimacy of IR is that it can be seen as focusing on the importance of seeking symbolic fit or “doing the right thing” in the eyes of society or stakeholders (van Bommel, 2014). It is acknowledged that the traditional financial reporting practices focus more on economic and financial information and that the increase of public awareness on social and environmental problems has forced companies to also document their sustainability agenda in their corporate reports (Horrach & Socía-Salva, 2011). However, current presentation of this sustainable information has been seen as separated from the financial aspect of the companies implying the lack of dependency of this information within a company (Jensen & Berg, 2011). Therefore, the publication of a single report combining global financial statements, social and governance reports and other key elements, in order to present a more holistic picture of the business, as offered by IR, is seen to be doing the right thing. Such information is claimed to be able to fulfil the needs of the stakeholders in their decision making process (Vancity, 2005). Most importantly, it is claimed as to be able to provide solution to investors and other stakeholders in achieving accurate valuation of a company’s value amidst the ever increasing amount of information disclosed by the companies (Hutton, 2004).

With the pressure given by the government/public for companies to take measures in educating and communicating to the public changes that have been made and reporting becoming a mean to legitimize action taken by companies, companies are now expected to transform their corporate reporting into IR. This has led to an apparent link between accounting research and legitimacy theory that revolves around companies transformation into IR.

It is notable, however, research on IR is still at its infancy stage as compared to research on sustainability reporting. Much of the research is also focusing more on stakeholders’ perspective instead of looking at the actual implementation of IR at companies’ level (see for example van Bommel, 2014; Rensburg & Botha, 2013). Frías-Aceituno et al. 2013), is among few studies conducted from the perspective of the companies. Using 750 international companies’ reports from year 2008 until 2010 as their samples, the study examined the effect of the legal system on the development of IR. Their findings show that companies located in countries with civil law and have high low and order indices, have more chances to produce a broad range of IR report, thus favouring decision-making by the different stakeholders.

To the knowledge of this present study, there has been very limited studies conducted within the context of Southeast Asian counties. Sigh, Sze Wei, and Kaur (2012) is an example of IR study that has considered Malaysia as one of their research setting. The study, however, only provides a regulatory review on IR between developed and developing countries, which includes Malaysia. Another major study conducted within the setting of Malaysia and Singapore is a study conducted by KPMG and National University of Singapore (NUS) in year 2015. As compared to Sigh et al. (2012), KPMG and NUS (2015), study provides a much focus analysis on companies in Asian Pacific setting, which includes Malaysia and Singapore. The study provides meaningful evidence to suggest that Asian Pacific companies that adopt IR as a mean to address the gap in traditional reporting are associated with better capital market performance (KPMG and NUS, 2015).

The KPMG and NUS (2015) study has provided a good basis for future research on IR in Southeast Asia setting. However, more research is needed to analyse the extent of which IR has been implemented, particularly among the early adopters of IR. Therefore, taking into consideration the growing importance of IR in Malaysia and Singapore, and the lack of study on IR within Southeast Asia setting, it is the aim of this present study to provide an in-depth analysis on the existence of IR related element in the annual report of Malaysian and Singapore public listed companies, respectively. Additionally, this study will also analyse, whether or not, there is significant difference between companies from these two countries that have both expressed their support on the implementation of IR. Singapore, in particular, as compared to Malaysia, is one of the countries that have been included as part of IR pilot project. Therefore, it would be interesting to know where Malaysian companies stand as oppose to Singapore companies when it comes to IR.

Research Questions

Taking into consideration the gap identified in the existing literature, the following are research questions for this present study:

To what extent present corporate reports of Malaysian and Singapore companies consistent with the proposed IR framework?

Is there any significance difference, within the context of IR framework, between Malaysian and Singapore companies’ corporate reports?

Purpose of the Study

The objectives of this study are:

To analyse the extent of which Malaysian and Singapore companies’ corporate reports consistent with the proposed IR framework.

To examine whether or not there is significance difference, within the context of IR framework, between what is currently reported by Malaysian and Singapore companies.

Research Methods

The study focuses on the IR practices of 30 largest companies ranked by market capitalization listed on Malaysia and Singapore stock exchange, respectively. The decision to choose only 30 of the largest Malaysian and Singaporean companies consistent with the view proposed by Guthrie, Petty, and Ricceri (2006). Guthrie et al. (2006) claim that large companies have the financial resources needed to be more advanced and innovative which eventually enhance their capabilities to improve their corporate reports. The year 2016 was chosen to be the latest corporate reports, particularly annual reports, available at the time this study was conducted. The reports are considered as appropriate tools to measure the comparative position and trends of information between these countries. Annual reports were obtained from the Bursa Malaysia and Singapore Exchange website. This is largely contributed by the fact that all annual reports are mandatory to be produced annually. IR related elements are examined in the annual reports of a total of 60 companies through content analysis. The use of content analysis to access the IR practices of the companies is justified. Mouton (2005) asserts that content analysis can be used to analyse documents and reports according to the content categories based on the rules of coding. The following content analysis guidelines were used for the purpose of coding the integrated reporting and traditional sustainability report practices (refer Table I).

Adopting the approach used by KPMG and NUS (2015) study, the IR related elements were divided into two sets of index i.e. content element and guiding principles (refer to Table

Findings

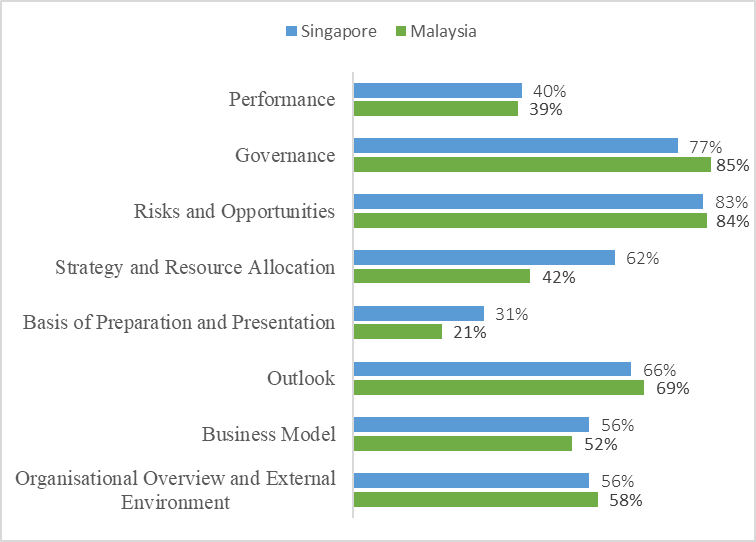

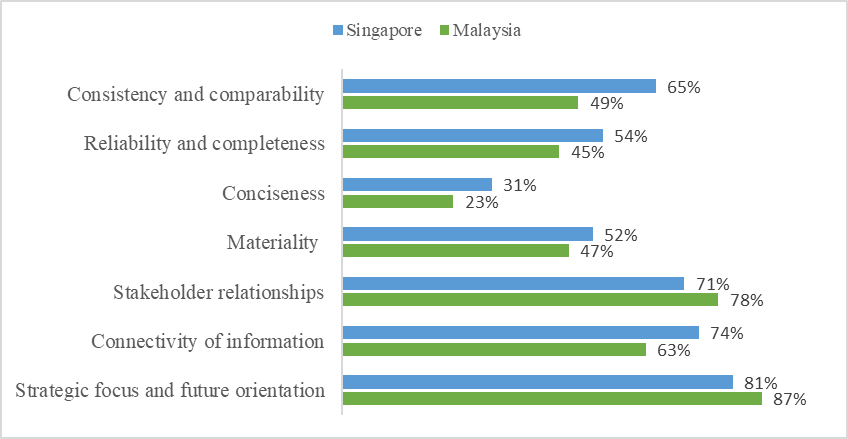

A total of 8 content elements and 7 guiding principles have been identified and analysed with each elements contents a set of indicators that are expected to be found in the IR report. Figure

Looking at categories of information being reported by companies from both countries, information on governance and risk seem to be the most reported items with Malaysian companies scoring the highest at 85 and 84 percent respectively. Higher scores shown by companies from both countries could be attributed by the fact that these are items that are commonly reported under the code of corporate governance (CCG). On the other hand, as these are items that are commonly falls under the mandatory requirement of CCG, this may impose question on why the score has not reached 100 percent. Additionally, element that requires companies to explain basis of their preparation and presentation also seems to score the lowest for both countries with 21 and 31 percent each indicating lack of willingness to illustrate how concept such as materiality being implemented in preparing the reports.

Figure

The mix results shown by the two countries provide assurance that despite Singapore is the pioneer of IR in Southeast Asia region, Malaysian companies are not very far behind from what is expected under IR. To further support this claim, a test of difference was conducted to see whether or not there is significance difference between what have been reported by Malaysian companies and the Singapore companies. Different set of tests were conducted for each element depending on normality of the data.

Table

The non-significant difference between the two countries could be attributed by the fact that both countries have not make it compulsory for their companies to implement IR. Additionally, the freedom to implement IR enjoyed by their public listed companies could also explain why there is no standardised focus of IR exhibited by the two countries. While the lack of focus on certain IR indicators do not provide indication that one is better than another, it is possible that this is due to differences in the culture or direction adopted by respective countries. Factors leading to these difference can be a potential research area that is worth looking at to provide further understanding on the IR practices in these two countries.

Conclusion

The aim of this study has been to provide insights on the extent of IR related elements in the 60 public listed companies of Malaysia and Singapore (30 companies each) as well as to see whether or not there is significant difference between these two countries when it comes to IR. The findings of both countries validate the claim that the countries are encouraging their public listed companies to implement IR. On the other hand, the findings also indicate there are differences in the way each of the company reports each of the IR elements with each company focusing on different type of elements. The difference could suggest future research looking at factors leading to these differences. Nonetheless, it is important to highlight that while the findings cannot be generalized, due to the small sample size, this study has provided evidence that there is no significant difference between Malaysia and Singapore when it comes to the extent of IR information found in their respective companies’ annual report. Additionally, the findings also provide practical indication to Malaysian and Singapore regulators that converting into IR is not something that is impossible to achieve. It is the role of the regulators to facilitate further provision of such transformation without compromising the need of various parties including the companies. One of the limitation of this study is that it only covers two countries leading to smaller sample size. The study could be further extended to a larger sample size with representatives from other Southeast Asian countries who have also expressed their intention to convert to IR.

Acknowledgments

This study wish to acknowledge the support given, through the grant no. 10289176/B/9/2017/20, by Universiti Tenaga Nasional (The National Energy University) and its Innovation & Research Management Center (iRMC) in making sure this research achieves its objective.

References

- Adams, S., J. Fries, & Simnett, R. (2011). The journey toward integrated reporting. Accountants Digest, 558, 1–41.

- Aras, G., & Crowther, D. (2009). Corporate sustainability reporting: a study in disingenuity? Journal of Business Ethics, 87 (S1), 279-288.

- Cohen, J., Holder-Webb, L. L., Nath, L., & Wood, D. (2012). Corporate reporting on nonfinancial leading indicators of economic performance and sustainability. Accounting Horizons, 26, 65–90.

- Eccles, R.G.. & Kruz, M.P. (2010). One Report - Integrated Reporting for a Sustainable Society. Wiley.

- Frías-Aceituno, J. V., Rodríguez-Ariza, L. & García-Sánchez, I. M. (2013). Is integrated reporting determined by a country’s legal system? An exploratory study. Journal of Cleaner Production, 44, 45-55.

- Guthrie, J., Petty, R., & Ricceri, F. (2006). The voluntary reporting of intellectual capital: Comparing evidence from Hong Kong and Australia. Journal of Intellectual Capital, 7(2), 254–271. doi:10.1108/14691930610661890

- Horrach, P., & Socias-Salvà, A. (2011). The attitude of third sector enterprises towards the disclosure of sustainability information: a stakeholder approach. Revista de Contabilidad-Spanish Accounting Review, 14(1), 267–297.

- Hutton, A. (2004). Beyond financial reporting: An integrated approach to disclosure. Journal of Applied Corporate Finance, 16(4), 8–16.

- International Integrated Reporting Committee – IIRC (2011). Towards Integrated Reporting. Communicating Value in the 21st Century. Retrieved from http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2011/09/IR-Discussion-Paper-2011_spreads.pdf

- International Integrated Reporting Committee – IIRC (2013), The International IR Framework, The International Integrated Reporting Council, London. Retrieved from http://integratedreporting.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/13-12-08-THE-INTERNATIONAL-IR-FRAMEWORK-2-1.pdf

- Jensen, J. C., & Berg, N. (2011). Determinants of traditional sustainability reporting versus integrated reporting. an institutionalist approach. Business Strategy and the Environment, 21, 299-316.

- KPMG & National University of Singapore (2015). Towards Better Business Reporting Integrated Reporting and Value Creation. Retrieved from https://www.kpmg.com/SG/en/.../Towards-Better-Business-Reporting.pdf

- Mouton, J. (2005). How to succeed in your master’s and doctoral studies. A South African guide and resource book. Pretoria: Van Schaik.

- Rensburg, R., & Botha, E. (2013). Is Integrated Reporting the silver bullet of financial communication? A stakeholder perspective from South Africa. Public Relations Review, 40(2), 144–152.

- Sigh, J., Sze Wei, S., & Kaur, K. (2012). Integrated reporting – A comparison between developed and developing countries. South East Asian Journal of Contemporary Business, Economics and Law, 1, 81-84.

- Stubbs, W., & Higgins, C. (2014). Integrated Reporting and internal mechanisms of change. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27(7), 1068-1089.

- van Bommel, K. (2014). Towards a legitimate compromise? An exploration of integrated reporting in the Netherlands. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 27, 1157-1189.

- Vancity. (2005). Integrated reporting: issues and implications for reporters. Solstice Sustainability Works, Inc. Retrieved from https://www.vancity.com/SharedContent/documents/IntegratedReporting.pdf.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

31 July 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-043-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

44

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-989

Subjects

Business, innovation, sustainability, environment, green business, environmental issues, industry, industrial studies

Cite this article as:

Abdullah, N. W., Husin, N. M., Salleh, S. M., & Alrazi, B. (2018). Integrated Reporting: A Comparison Between Malaysian And Singapore Public Listed Companies. In N. Nadiah Ahmad, N. Raida Abd Rahman, E. Esa, F. Hanim Abdul Rauf, & W. Farhah (Eds.), Interdisciplinary Sustainability Perspectives: Engaging Enviromental, Cultural, Economic and Social Concerns, vol 44. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 97-107). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.07.02.11