Abstract

The current article aims to present the partial findings of a doctoral research that examined Being on Stage Intervention Program (BoSIP), which is a program that constitutes an integral part of higher education academic curriculum designed to promote student resilience. Although the scientific literature offers extensive insight on the subject of resilience, sparse information has been found on the manner by which a theatre-based program may promote the resilience of academic students through playing the role of audience as part of program design. Our present study utilized qualitative constructivist research methodology using semi-structured interviews and open-ended questionnaires. 35 students participated in the research on a voluntary basis. The collected data was analysed according to the content analysis method using a narralizer. The research findings derived from content analysis revealed, among others, the powerful potential of being an audience that involves experiencing a dual role fortifying resilience. As audience, program participants underwent processes of self-awareness and catharsis alongside training in identification, acceptance, and lack of criticism when coping with difficulties, validating fears and anxiety which actors on stage experience when performing. Ultimately, the research offers an innovative method of utilizing theatre group work for the facilitation of resilience during academic studies.

Keywords: Dual audience rolepsychological resiliencetheatre group workBoSIP

Introduction

Psychological resilience is a collection of skills assisting the individual in regulating emotions that hinder adequate response to a new reality (Berger & Lahad, 2011). Psychological resilience includes numerous components related to the individual's inner strengths, character, interpersonal skills and abilities. Indication of psychological resilience correlates with effective adaptability and coping with situations of stress, pressure and adversity (Grotberg, 2005). Other theoreticians define psychological resilience as coping resources, a collection of inner assets or personal and social abilities associated with healthy development (Dunham, 2002; Bonnie, 2004).

Hobfoll, Briggs-Phillips & Stines (2003) Resource Conservation Theory contends that each human being holds unique perceptions regarding their personal resources and strives to conserve and protect these resources in face of local threat and ongoing pressure. Thus, mental resilience is comprised of mental, affective, physical, social and spiritual components. These include concepts such as self-awareness, self-confidence, perceived sense of overcoming, acceptance and giving, wellbeing, and flexible world views and behavior (Bonnie, 2004; Seligman, 2010).

Being on Stage Intervention Program (BoSIP) is a drama therapy program designed to advance mental resilience utilizing four working principles taken from theatre art: role play, being on stage before an audience, improvisation, and autobiographical presentation (Doron Harari, 2015).

The current article focuses on research results relating to the question: "What processes do program participating students undergo when playing the role of audience and what is the importance of these processes?" Current research findings indicate that BoSIP participants playing the role of audience undergo processes associated with two major fields of knowledge. These will be presented hereby in view of professional theatre art literature concerned with the role of audience in theatre, and professional literature from the field of drama therapy group therapy relating to processes group members undergo.

The role of audience in theatre art

In theatre art, the audience forms the center point whom actors and performance are designed to serve, conveying to the audience an experience or knowledge aimed to satisfy and please in return for applause (Rozik, 1991). Furthermore, numerous researchers claim that theatre constitutes an artistic medium most effective and adequate for expressing questions and dilemmas of human society, enabling experiencing, insight, and learning of values (Applebaum, 2007; Brockett, 1970; Boal,2000; Finegold, 1996). Since the age of antiquity, theatre has served as an educational instrument for relaying messages, reflecting and shaping public opinion. The theatrical experience is a primary experience stemming from ancient rituals from which theatre originates, the ritual of Dionysus that birthed tragedy and comedy in ancient Greece. This is an experience that is based upon sharing and identification of actors and audience (Nagid, 1996). Theatre is alike a "mirror" that reflects the world, where theatrical experience affords spectators identification with the world of the other, as well as familiarization with a world that varies from their own (Rapp, 1980).

The medium of theatre carries enormous power in providing a different point of view and broadening perspectives. Theatre can also educate towards involvement and encourage shaping of personal and collective identity (Applebaum, 2013). In his notable Poetics (Aristotle, 2002), Aristotle states that the audience is meant to undergo catharsis, i.e. experience emotions of compassion, fear, and hope that no evil shall befall the hero. Hence, the role of the audience is not solely to watch the performance for mere enjoyment but also to respond, become excited, protest, hail, and demonstrate sympathy, empathy or antipathy towards the dramatized stage events. Thus, theatre affords the audience entertainment and escape from mundane concerns alongside learning and affective engagement. Spectators seek in theatre in general and drama in particular meaning that relates to their personal life experience, striving to better understand themselves and their life purpose via encounter and confrontation with the dramatic theme (Orian, 1998).

Overall, the encounter which takes place between the spectator audience and the actor forms theatre's most essential component (Grotowski, 1968): it is where dialogue develops, not necessarily verbal, on themes common to actors and spectators where spectators experience stage events as part of the vital flow of their own lives. Even if they do not cry or laugh or respond instantaneously, they nonetheless undergo an experience that momentarily disengages them from everyday concerns and adversities. Upon exiting the theatre hall, they will not be in the same state as when entering it, and they will return seeking for that memorable experience of magical moments (Nagid, 1996).

The processes of experience and identification the audience undergoes can solely occur under the condition that the theatrical convention of as if is sustained between audience and actors. The illusion created by the actors on stage must be accepted as absolute reality so as to produce effective pleasure and learning (Stanislavski, 1966; Applebaum, 2007). Brook (1991) and Grotowski (1968) were the first theatre persons to breach the theatrical convention separating stage and audience contending that there is no difference or borderline between stage and audience. The space in its entirety affords actors to perform everywhere and at every possible corner as though audience as well as actors are on stage [throughout history there were theatres that breached this gap-barrier between audience and stage, however specification of this theme is too long to be included in current article].

The role of audience in drama therapy and group therapy

While theatre focuses on professional outcome of performance before an audience and impact on audience (Brockett, 1970), drama therapy utilizes theatre art aimed at empowerment and therapy (Bailey, 2009; Jennings, 2012).

Drama therapy is a therapy technique that uses dramatic expression and creativity processes borrowed from theatre art, acting and performance with the objective of enhancing personal development and mental health. In drama group therapy, participants experience various roles each session, transitioning from actor role to audience role. The audience plays a significant role in group dynamics, providing support and creating perspective through processes of identification, comprehension, and change of stances (Jones, 1996). The audience perceives and senses on stage events and responds; audience response in projected back to the stage producing reciprocity between actor and audience (Doron Harari, 2014). Thus, participants playing the role of audience in drama therapy are afforded an opportunity to observe life dramas, take an interest, experience, learn, understand, be empowered and involved. Furthermore, the audience is enabled to see the overall picture of the actions and derive its own conclusions (Jennings, 2012).

Theatre work is group work. Group space inherently affords room for social interactions, social formalization and experience that may lead to transformation, empowerment and healing (Yalom, 2005; Offner, 2011). Hence, theatre work processes are group processes that enable self-expression and learning of leadership when assuming director role, alongside learning of devotion, flexibility, service and empathy in the role of actor. Group members as audience carry the role of fortifying visibility of participant (Oren, 1997; Bailey, 2009; Doron Harari, 2014). The audience's gaze upon the actor is particularly significant in that it conveys empathy, identification, and confirms existence (Kohut, 1978). In this respect, the stage reenacts the primary existential experience of a baby under their mother's gaze, a gaze from which springs the true lively self (Ingerman, 2003).

The spectator audience serves several purposes: producing a sense of confidence, determining clear boundaries between inrolling and outrolling, and increasing concentration and focus. The transition between spectator and actor can serve as an axis of change affording insight and perspective. Spectator audience presence can serve as supporters, confronters and guides accompanying the actor and dramatized character (Jones, 1996). Ergo, audience role can change from one minute to the next, where the participant is momentarily an actor going on stage and playing a character in their own performance, in the next playing a character in another member's performance, followed by returning to play the role of spectator audience.

Additionally, the audience undergoes an experience of identification or alienation offering in both cases the prospect to reflect upon one's personal life and become actively involved in on stage events (Doron Harari, 2014). As commonly most people engage with similar themes, this affords identification with narratives presented on stage. In other words, the narrator's story touches each audience participant's personal stance thereby allows identification (Offner, 2011), release and therapeutic introspection (Oren, 1997).

Problem Statement

On Being on Stage Intervention Program – BoSIP (Doron Harari, 2015)

BoSIP is a drama therapy program that utilizes theatre art principles. The program constitutes an elective course as part of Education undergraduate studies curriculum. The objective of the course is to afford students to experience, in practice, work conducted by means of theatre art that fortifies personal resilience, alongside gaining powerful tools for strengthening resilience of populations with which students work in field work context. Program work is conducted in group format throughout one semester. BoSIP invites the participant to be active as actor, director and audience. Program participants experience aforementioned theatre principles and transition between role of audience and role of actor at each session throughout. BoSIP is a modular program based on an overall objective and four theatre working principles, while program course is determined by the instructor through attentiveness to participants' needs and mood, formulated group space and aroused affective contents.

Research Questions

Research question was as follows: "What was your experience when playing the role of audience in BoSIP, and how did it impact your life?"

Purpose of the Study

Research objective was to examine audience experience in BoSIP, and whether this experience promotes resilience.

Research Methods

The research used qualitative constructivist methodology. Research tools were 10 semi-structured interviews and 25 open-ended questionnaires, collected two weeks following program completion. Research population consisted of 35 volunteer students. Data was analysed using content analysis method by means of narralizer, categorization and conceptualization.

Findings

Research findings depict that the experience of playing the role of audience was comprised of four categories: (1) identification with dramatized character and narrative; (2) identification with participant group members when in role of actor; (3) benevolent eye and freedom from criticism; (4) introspection leading to awareness up to change in self-management.

Identification with dramatized character and narrative

As found in research findings, the first experience described by participants was one of identification with performed narrative surfacing emotions that included excitement and pleasure. Identification with the character played on stage and their presented narrative afforded introspection and behavioral change.

"As an audience, you undergo upheavals and emotions which the actors relay to you just like in a movie or a good book, and I enjoyed every second. I recall how it truly opened my mind and made me think that maybe I too was in the wrong. Following the exercise my friend and I made up." (R)

"Watching the figure aroused in me emotions that are, at times, repressed, and I think that the actual watching, where at times I felt as though I was looking in the mirror, enriched me very much." (S)

Identification with participant actor

The second experience described by participants, as findings indicate, was identification with participant-actor entailing identification with senses of courage, partnership and commitment. As participants are acquainted with one another, they are able to identify with their group peer and the notion of courage required in acting and performance which they may further utilize to leverage their own when going on stage.

"For me, it was important to provide an appropriate, respectful and encouraging address to the actor because it is reciprocal, now he is performing and I'm next. The role of audience is significant in that it contains respect and full attentiveness. It is important to make room for the other too." (A)

"It didn't matter what they were performing – it came from the inside and it was lively and a pleasure to witness. I was surprised by people's courage and more than anything by the uniqueness of each and every one. As audience I was fascinated. Later on it was easier for me to go on stage." (D)

Benevolent eye and freedom from criticism

Findings depict the third experience described by participants as one of being able to observe the other favourably and acceptingly without criticism or judgment. In fact, the opportunity to observe another person uncritically invites and generates non-judgmental self-observation.

"From the moment the instructor stated that there is no judgment when serving as audience I felt how I was completely open to what was taking place in the classroom, observing everything favorably and uncritically, with respect towards whoever was on stage as well as towards myself." (A)

"It was interesting for me and I was glad to see which orientations my group peers took for their performances. In the beginning of the course I was a little critical towards some of the group members regarding the manner by which they chose to present a particular thing or lack of seriousness on stage that was probably due to embarrassment, but by mid-course I released my feelings and watched the performances from a benevolent and accepting stance." (L)

Introspection leading to awareness up to change in self-management

Findings show that playing the role of audience enabled participants to observe themselves, discover new things or confront familiar issues, where awareness of existing themes generated change resulting in improved and more compatible self-management.

"I learnt about my criticism and judgment. When you are in the audience and observe someone who is releasing their inhibitions and acting without "When you are the audience you make yourself completely available for true observation of whoever stands before you, an observation that personally has led me many times to personal introspection, to learn from the other, and I believe to think about things in depth and examine them in me. The experience aroused in me many questions about myself. To examine yourself through watching the other, seeing them act, trying to strongly connect, learn them and from them and observe how they perform and how it may improve the way I do things in the future." (S)

Conclusion

Identification with dramatized character and narrative

Participants conveyed undergoing an experience of identifying with the dramatized character and their performed narrative arousing emotions, expanding awareness, and generating intent to change behavior similar to the contentions of Brockett (1970), Rapp (1980), Aristotle (2002), Offner (2011), Jennings (2012), and Doron Harari (2014). The dramatized character's narrative coincides with audience's personal narratives enabling identification which in turn enriches and enhances behavioral change (Applebaum, 2013). This process of identification with dramatized character and narrative is made possible due to the theatric convention of as if, where the audience consents to relate to the fictional world presented on stage, character and narrative, as though it is actual reality (Stanislavski, 1966; Rozik, 1991; Orian, 1998). Being in the role of audience further includes the element of pleasure it entails, i.e. a pleasurable experience, aligning with literature that portrays theatre as a place of pleasure, entertainment and laughter (Stanislavski, 1966; Finegold, 1996).

In conclusion, identification with dramatized character and narrative generates pleasure, increases awareness, enriches, alters perceptions and changes behavior and these, in turn, all strengthen psychological resilience.

Identification with participant actor

Findings indicate audience's identification with the participant-actor who is their group peer. Contrary to theatre audience who are not personally acquainted with the actor, BoSIP participants are familiar with one another and share program course. This perceived sense of affiliation and partnership with the participant-actor is thus intensified in light of the sense of courage required for performing and being on stage. Moreover, program audience remains aware of the fact that it is their group peer who stands and acts before them. Brecht (in Brockett, 1970), was one of the first who contrary to the prevalent approach that sought audience identification with actor aimed at disconfusing boundaries between imaginary stage world and reality so as to propel the audience to think, change stances and act. Accordingly, BoSIP orients the audience to be alert and active in personal life. Findings further indicate that the audience holds a sense of responsibility and respect towards acting participants and experiences giving. Giving in itself is a therapeutic experience that promotes resilience (Yalom, 2005). That is, identification with participant-actor affords experiencing giving and meaningfulness as well as sensing courage to act. All of these elements fortify spectator's psychological resilience.

Benevolent eye and freedom from criticism

Theatre literature does not contain reference to or the directive of observing with a benevolent eye. Contrarily, in drama therapy group therapy in particular and group therapy in general there is salient orientation towards open attentiveness and acceptance of the other (Yalom, 2005). The theme of acceptance is discussed in literature primarily in the context of groups, contending that when a person is able to accept the other self-acceptance ensues, further leading to self-empowerment and development (Berman, 2017). Thereby, freedom from criticism and judgment, and perceiving the other benevolently and respectfully produce an experience of self-acceptance thereby constitute important factors constructing psychological resilience.

Introspection leading to awareness up to change in self-management

Additional research findings relate to introspection and self-learning leading to awareness processes. Participants noted the prospect of introspection when serving in role of audience while gaining new insight about themselves and changing personal perceptions. These findings concur with both theatre literature and drama therapy group therapy literature which discuss an experience that leads to change and construction of personality (Applebaum, 2013; Nagid, 1996). Multiple drama therapy theorists speak of a process that carries the experiential element of learning, understanding, fortification, empowerment and change of stances (Orian, 1998; Jones, 1996; Jennings, 2012), alongside release and therapy (Oren, 1997; Yalom, 2005; Offner, 2011). Therefore, spectator's experience of identifying with the participant-actor and the character they dramatize on stage affords a process of identification and self-awareness, introspection and self-examination as well as self-acceptance that all enrich, empower and advance psychological resilience.

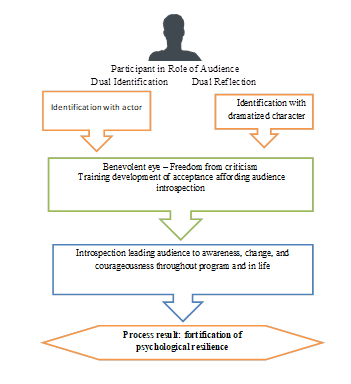

The conclusion arousing from research findings indicates that the participant as spectator-audience simultaneously experiences two processes of identification, i.e. dual identification from dual reflection. One reflection occurs in view of the participant-actor, while the second reflects from dramatized character and narrative. Throughout the program, the audience maintains these two reflection venues open.

The following illustration presents the dual reflection-identification process:

The participant in role of audience experiences double identification, i.e. dual role. These two reflections produce simultaneous dual identification. Throughout the program, attention is focused at training the audience in observing the other with a benevolent eye and free of judgment. Such training in freedom from criticism releases the participant audience affording pleasure and affective experience. Furthermore, it develops a sense of acceptance, acceptance that is directed towards the other, towards the stage, and back to the self as self-acceptance. As reported by research participants, benevolent eye training generates processes of identification leading to introspection and self-awareness where these, in turn, lead to change in stances and perceptions regarding the other and the self, as well as change in behavior and self-management within the program. Thus, the process of identification-benevolent eye-acceptance-awareness supports and propels participant audience to dare throughout the program in sharing and performing on stage. This process further touches and impacts participants' private lives beyond the program.

In conclusion, at the end of a theatre show alike at the end of a performance in BoSIP, the audience commonly applauds the actor for their work. The current article directs the applause towards the audience. The article follows and observes audience experience in the program and the resilience fortification processes they undergo. The experience of being in the role of audience in BoSIP prospects affective processes, identification and awareness processes, alongside training in benevolent eye and acceptance that all strengthen participating students' psychological resilience which assists and supports daily management.

References

- Applebaum, A. (2007). The theater as a tool for education and training; Review forces and its uses as a source known efficacy of change and learning. Doctoral Dissertation. Technion, Haifa, Israel (Hebrew)

- Applebaum, A. (2013). Organizations Theater - From metaphor to intervention. : Retrieved from https://www.articles.co.il/article/164335. (Hebrew).

- Aristotle (2002). Poetics. Jerusalem: Magnes. (Hebrew)

- Bailey, S. (2009). Performance in Dramatherapy. Current approaches in Dramatherapy. Illinois: Charles. C. Thomas. pp. 374–389

- Berger, R. & Lahad, M. (2011). Resilience and coping resources. Episode, Healing Forest, Kiryat Bialik: Ach. (Hebrew)

- Berman, A. (2017). The therapeutic group is at an advanced stage. Retrieved from http://www.aviberman.co.il/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id

- Boal, A. (2000). Theater of the Oppressed. . England .Pluto Press

- Bonnie, B. (2004). Resiliency: What We Have Learned. San Francisco, CA:WestED.

- Brockett, O. (1970). History of the theatre. Boston: Allyn & Bacon.

- Brook, P. (1991). The Empty Space. Tel- Aviv: Or Am (Hebrew)

- Doron Harari, M. (2014). Stage and Soul: The Therapeutic Autobiographical Theatre as a Model In Dramatherapy..in Berger, R. (ed.) Creation – the Heart of Therapy. Kiryat Bialik: Ach. pp. 152-192. (Hebrew)

- Doron Harari, M. (2015). "To Be On Stage Means To Be Alive" Theatre Work with Education Undergraduates as a Promoter of Students' Mental > Resilience ☆ Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences Volume 209, 3 December 2015, Pages 161-166

- Dunham, J. (2002). Stress in teaching. Routledge.

- Finegold, B. (1996). Why drama, education and theater. Tel- Aviv: Itab. (Hebrew)

- Grotowski, J. (1968). Towards a poor theatre. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Grotberg, E. (2005). The International Resilience Project: Research, Application, and Policy. Civitan International Research Center, UAB.

- Hobfoll, S. E., Briggs-Phillips, M., & Stines, L. R. (2003). Fact or artifact: The relationship of hope to a caravan of resources. Between stress and hope: From a disease–centered to a health–centered perspective, 81-104.

- Ingerman, R (2003). The connection between the actor's role to his stage performing, profession and everyday life. Master's Theses. Lesley University (Hebrew)

- Jennings, S. (2012). Theatre of resilience: Ritual and attachment with marginalized groups – “We are all born dramatised and ritualised. In C. Schrader (Ed.). Ritual theatre: The power of dramatic ritual in personal development groups and clinical practice. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishing

- Jones, P. (1996). Drama as Therapy - Theatre as Living. UK: Routlege, Ch 5, pp 99-125.

- Kohut, H. (1978). Psychology of the Self and Human Sciences. Tel- Aviv: Bookworm. (Hebrew)

- Nagid, H. (1996). Stage Language. Tel-Aviv: Sal Tarbut Artzi. (Hebrew)

- Offner, M. (2011). The therapeutic effect of Playback Theatre on those who practice it according to their perception of Players Playback. December, Vol. 2, Issue 3, Haifa: Haifa University. 106-109. (Hebrew)

- Oren, N. (1997). From Theatrical Stage to Therapeutic Stage. Master's Theses. Lesley University. Thesis. (Hebrew)

- Orian, A. (1998). The open circle- a stage and screen art's book. Bney brak: sifriyat hapoalim. (Hebrew).

- Rapp, U. (1980). The World Of Play. .T.A. Broadcast University Ministry of Defense (Hebrew)

- Rozik. E. (1991). The language of the thetron. Dvir Publishing Ltd. Tel Aviv (Hebrew)

- Seligman, M. (2010). Flourish: A Visionary New Understanding of Happiness and Well-being. New York: Free Press.

- Stanislavski, C. (1966). An Actor Prepares. Tel Aviv: Tarbut Ve-hinuch. (Hebrew)

- Yalom, I.D. (2005). The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy. New York: Basic Books.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 June 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-040-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

41

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-889

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Harari, M. D. (2018). Applause The Audience: Benefits Of Being The Audience In Theatre Group Work. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2017, vol 41. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 541-549). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.06.64