Abstract

Keywords: Dance/movement therapymovement parametersemotional intelligenceself-efficacynonverbal knowledge

Introduction

This article presents findings from the pilot study of a doctoral research study in the field of dance/movement therapy. The research seeks to demonstrate the relationship between a unique self-supervision model and changes in movement.

Literature from the past few years has discussed dance as a multisensory experience that provides a “more complete mode of self-expression than speech or writing” (Hanna, 1995). Dance addresses the person on several levels, namely at the bodily, emotional, cognitive, and cultural levels. Dance supplies us with ways of feeling our physical self and detecting solutions for problems in everyday life (Hanna, 2006). Our body posture and the way we move, affects how we perceive the world around us and how we feel, which is continuously being uncovered by the growing research in the field of embodiment (Fuchs & Koch, 2014; Koch, 2011, 2013, 2014; Koch, Morlinghaus & Fuchs, 2007).

Recently, research in this area of supervision has examined the effects of supervision on dance/movement therapy students and therapists. These studies can be divided into two main categories: Those that examine the effects of using verbal language to relate to movement on psychological indicators, such as emotional intelligence and self-efficacy (Wiedenhofer & Koch, 2017) and those that study the effects of movement and dance use on body/movement indicators that reflect dynamic psychological dimensions (Federman, 2001; Ko, 2014). Models are lacking for supervision and research that integrate these two positions (Shalem-Zafari & Grosu, 2016).

This study aims to demonstrate the connection between a unique self-supervision model and changes in movement. It utilizes a tool called Epimotorics’, which is an approach that provides a solid basis for movement analysis (Specktor, 2015; Skrzypek, 2017). This pilot is part of the larger study examining the effects of this new self-supervision model on movement indicators. The larger study will examine the changes in movement, as well as the relationship between the movement indicators and emotional intelligence and self-efficacy.

The current study is based on a workshop given at the Seventh Annual Expressive Arts Therapies Summit in 2016 in New York City. The workshop was based on this self-supervision model. The present study rests upon two important theories in dance/movement therapy: Authentic Movement (Payne, 2008; Whitehouse, 2000) and the Epimotorics` (Shahar-Levy, 1996, 2004, 2012, 2015; Specktor, 2015; Skrzypek, 2017). Both theoretical approaches relate to the mutual influence between words (cognition) and movement (emotion); this reciprocal relationship is a central concept in dance/movement therapy.

Problem Statement

The pilot study is based on a short-term intervention

Clearly the number of participants in such a study is small. However, there are studies in the literature with a small number of participants; these include a study by Wiedenhofer, Hofinger, Wagner, & Koch (2016) with 6 participants, examining health effects of non-goal-orientation in movement. Widenhofer & Koch (2017) write about ways of utilizing a small sample size. They argue that when research demonstrates the occurrence of certain effects in a smaller sample group, one can frequently assume that similar effects will be present in larger sample sizes, as well.

Research Questions

The broader research question

In what ways does the self-supervision model facilitate dance/movement therapists’ movement ability, emotional intelligence, and self-efficacy?

Research question of the pilot study

In the pilot study, we examine which movement indicators are affected by the use of the self-supervision model, and how they are affected.

Purpose of the Study

General research goal

The general research goal of the larger study is to develop a model of self-supervision based on Authentic Movement and Epimotorics` movement analysis.

Subsidiary research aims:

To examine the influence of a self-supervision model, integrating Authentic Movement and Epimotorics` movement analysis, on novice dance movement therapists’ movement ability, emotional intelligence, and self-efficacy.

To examine the relationship between the movement and these psychological measures, i.e. emotional intelligence and self-efficacy.

Purpose of the pilot study

The goal of this pilot study is to provide preliminary findings regarding the development of the self-supervision model based on Authentic Movement and Epimotorics’, while addressing the model’s ability to cause changes in the movement indicators. These indicators may predict a relationship between ways of moving and emotional intelligence and self-efficacy.

Research Methods

This research employed quantitative tools. The pilot study used filmed video recordings of the supervision workshop participants. The recordings filmed the participants’ movement before and after the training in the self-supervision model. The filmed movement was analysed using the Epimotorics’ movement analysis tool.

Research population

The group included six participants: Four dance/movement therapists, one clinical psychologist who integrates body/movement perspectives, and one music therapist who relates to the use of body/movement while clients are creating music during therapy.

Findings

The current research's motives are to provide preliminary findings regarding the development of the self-supervision model, which is based on Authentic Movement and Epimotorics’, as well as its ability to generate changes in movement indicators. The coming chapter will initially present descriptive statistics regarding the movement indicators, as ranked before and after the implementation of the abovementioned model. Afterwards, the statistical examination of the research hypotheses about the broadening of usage and actualization of the movement indicators due to the implementation of the self-supervision model will be presented.

Descriptive statistics

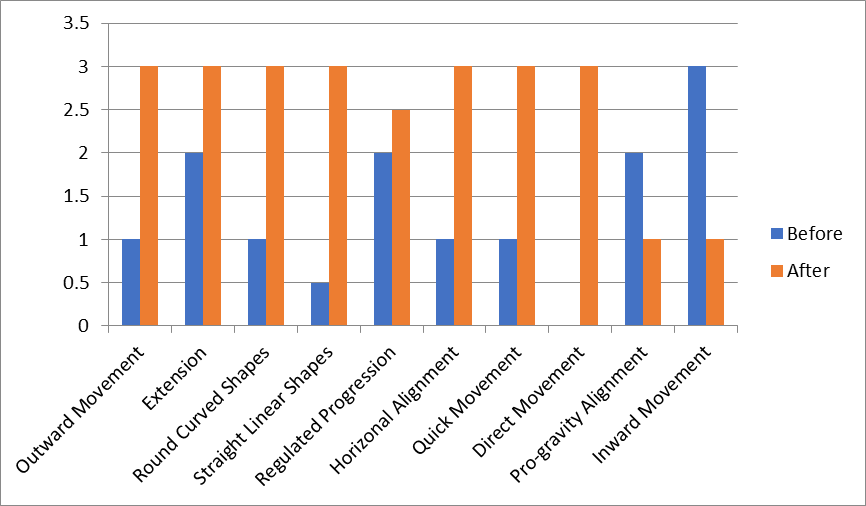

In order to examine the means and standard deviations of the research variables, a calculative transformation was conducted. Therefore, the movement indicators were ranked as followed: "0" = dormant, "1" = actualization potential, "2" = partial actualization, and "3" = complete actualization. For means and standard deviations, view table number 2.

From the presented data, it is noticeable that regardless of the baseline score, eight movement indicators were completely actualized after the implementation the of self-supervision model. Those indicators are: Outward movement, Round curved shapes, Straight linear shapes, Horizontal alignment shapes, Vertical alignment shapes, Quick movement, Continuous movement, and the Direct movement parameter.

Research hypothesis examination

The research hypothesis was that compared to the baseline measurement, after implementing the self-supervision model which is based on Authentic Movement and Epimotorics’, the movement indicators will change significantly. Because the data were derived from a small sample, a Wilcoxon Signed-Ranks Test was performed. The results indicated that post-implementation scores were statistically significantly higher than pre-implementation scores for Outward movement (

Examining the prevalence of 'extreme actualization'

It should be noted that during the examination of the data before the abovementioned statistical transformation, it was found that more than 30% of the participants were possessing extreme actualization

In addition, of the indicators that were just mentioned, 83% of the participants were found to extremely actualize the Indirect Movement indicator

Findings summary

The results show that some movement parameters were affected more than others. Of the 44 measures examined, 14 were statistically different after the implementation of the model. 2 of them were lower after the implementation, and the rest were higher. Of those that were higher after the implementation, 8 were significantly different, and 4 were marginally significant. One indicator, the Vibration Wavy Movement, was found to be difficult to detect though video. Two indicators remained after the implementation as they were before it (Rotation and Trunk Activation

Conclusion

Discussion

Much of these findings can be explained by examining the movement indicators in the context of the psychological content they reflect; this perspective views movement as a nonverbal language expressing meaningful information, which cannot and should not be overlooked. In this study, the motoric parameters that demonstrated significant changes are, according to psychological movement analysis tools (Shahar-Levy, 2015; Feniger-Schaal & Lotan, 2017), parameters related to attachment and connection. Thus changes in this movement area would reflect changes in the areas of attachment and connection. In order to more thoroughly establish this connection between the nonverbal information expressed by the body and its movement with verbal information, further research is necessary. (The doctoral research that this pilot study is a part of examines these connections by cross-examining movement information with emotional intelligence and self-efficacy questionnaires).

It appears quite clear that the self-supervision model affected the participants’ movement. We can relate to the movement indicators in which a significant change was present after using the self-supervision model as movement indicators that react significantly to the use of the self-supervision model (including 4 that had marginal significance). These indicators should be examined further in the context of psychological indicators, in order to understand the effects of this new self-supervision model on therapists. In light of the fact that, among the 44 indicators, 12 had a higher score after implementing the model (indicators 2, 12, 16, 17, 18, 24, 28, 29, 30, 31, 35,42), and 2 had a lower score after implementing the model (indicators 9 and 11), it appears important to examine both increase and decrease in movement potential actualization in the context of the psychological parameters. Additionally, there are indicators that did not lend themselves to examination through this method, e.g. Vibration Wavy Movement.

Conclusion

This pilot study aimed to produce preliminary findings regarding the effects of a unique self-supervision model on novice dance/movement therapists. The findings show a clear impact of the training in the self-supervision model on workshop participants; the findings also provide direction for greater specification of the study’s parameters. Further research aims to examine the correlations between the movement indicators and psychological measures, to assess the effects of the self-supervision model. The correlations tested in this research could lead to a breakthrough wherein movement indicators may reveal information about emotional intelligence and self-efficacy, and vice versa: Questionnaires on emotional intelligence and self-efficacy could provide information about one’s movement.

One of the most important things required of a therapist is the ability to create connection. The fact that the motor parameters that changed significantly in this study are reflective of attachment and connection quality may point to the supervision model’s ability to enhance therapist’s skills in this area.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Dahlia Zilbertal, whose partnership and cooperation made the New York workshop possible.

References

- Federman. D. J. (2011). Kinaesthetic change in the professional development of Dance Movement Therapy trainees. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 6(3), 195-214.

- Feniger-Schaal, R., & Lotan, N. (2017). The embodiment of attachment: Directional and shaping movements in adults’ mirror game. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 53, 55-63.

- Fuchs, T., & Koch, S. C. (2014). Embodied affectivity: On moving and being moved. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 508. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00508

- Hanna, J. L. (1995). The power of dance: Health and healing. Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 1(4), 323–331.

- Hanna, J. L. (2006). Dancing for health: Conquering and preventing stress. Lanham, MD: AltaMira Press.

- Ko, S.K. (2014). Korean Expressive Arts Therapy Students’ Experiences with Movement-Based Supervision: A Phenomenological Investigation. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 36, 141–159.

- Koch, S. C. (2011). Basic body rhythms and embodied intercorporality: From individual to interpersonal movement feedback. In W. Tschacher, & C. Bergomi (Eds.), The implications of embodiment: Cognition and communication (pp.151–171). Exeter: Imprint Academic.

- Koch, S. C. (2013). Bewegungs-Raum. raumbewegung und bedeutung [Movement-Space. spatial movement and meaning]. In B. Eigelsberger, M. Greenlee, P. Jansen, J. Schmidt, & A. Zimmer (Eds.), SPACES – perspektiven aus.

- Koch, S. C. (2014). Rhythm is it: Effects of dynamic body-feedback on affect and attitudes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 537. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00537

- Koch, S. C., Mergheim, K., Raeke, J., Machado, C. B., Riegner, E., & Nolden, J. (2016). The embodied self in Parkinson’s disease: Feasibility of a single tango intervention for assessing changes in psychological health outcomes and aesthetic experience. Frontiers in Neuroscience, 10, 287. http://dx.doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2016.00287

- Koch, S. C., Morlinghaus, K., & Fuchs, T. (2007). The Joy Dance. Specific effects of a single dance intervention on psychiatric patients with depression. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 34, 340–349.

- Payne, H. (2008). Supervision of dance movement psychotherapy: A practitioner’s handbook. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Shahar-Levy, Y. (1996). The visible body reveals the secrets of the mind: A body-movement mind paradigm (BMMP) for the analysis and interpretation of emotive movement. Jerusalem: Author’s Hebrew Edition.

- Shahar-Levy, Y. (2004). A body–movement–mind paradigm for psychophysical analysis of emotive movement and movement therapy. Jerusalem: Shahar-Levy.

- Shahar-Levy, Y. (2012). Development and body memory. Body Memory, Metaphor and Movement, 84, 327.

- Shahar-Levy, Y. (2015). Emotorics: A psychomotor model for the analysis and interpretation of emotive motor behavior. In S. Chaiklin & H. Wengrower (Eds.), The Art and Science of Dance Movement Therapy: Life is Dance, 2nd ed. (pp. 265–297). New York, NY: Routledge.

- Shalem-Zafari, Y., & Grosu, E. F. (2016). Dance Movement Therapy, Past and Present: How History Can Inform Current Supervision. The European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences: ERD 2016: Education, Reflection, Development, Fourth Edition.

- Skrzypek, H. A. (2017) Body Movement Music Score–Introduction of a newly developed model for the analysis and description of body qualities, movement and music in music therapy. Health Psychology Report, 5(2), 100-124.

- Specktor, M. (2015). A study of twins and coping with crisis using Emotorics. Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 10(2), 121-135.

- Whitehouse, M.S. (2000). The transference in dance therapy. In P. Pallaro (Ed.) Authentic Movement: Essays by Mary Starks Whitehouse, Janet Adler and Joan Chodorow (Vol.1)(2nd ed.) (pp. 63-73). London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. (Original work published 1977).

- Wiedenhofer, S.M., Hofinger, S., Wagner, K., & Koch, S.C. (2016). Active factors in dance/movement therapy: Health effects of non-goal-orientation in movement. American Journal of Dance Therapy,American Journal of Dance Therapy 1–13.

- Wiedenhofer, S., & Koch, S. C. (2017). Active factors in dance/movement therapy: Specifying health effects of non-goal-orientation in movement. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 52, 10-23.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 June 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-040-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

41

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-889

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Shalem-Zafari, Y., & Grosu, E. F. (2018). The Contribution Of A Unique Supervisory Model To Novice Dance/Movement Therapists. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2017, vol 41. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 330-338). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.06.40