Abstract

The English language has undergone immense changes throughout the 20th and the beginning of the 21st century. For various sociocultural and economic reasons, it has expanded beyond its inner circle of native speakers and has become a Lingua Franca, a means of communication between different people with different native languages. Today, more people speak English as a second or foreign language than those who speak it as their first language. Due to its spread and interaction with different cultures, the English language serving as a Lingua Franca takes on different forms and undergoes various changes. It has also become a language that is taught throughout the world and native English-speaking TESOL teachers can be found in many countries. These teachers are a unique population to be researched in order to understand the sociolinguistic changes that are happening to English. They are native speakers, who live in a foreign country. Their uniqueness lies in the fact that they are language teachers and therefore possess linguistic awareness. This article is a part of an ongoing research project that focuses on the effect of the local culture on the ESOL teacher. The article lays the theoretical basis for one of the research questions regarding the linguistic changes that native speaking ESOL teachers undergo while assimilating in a different culture. Do they become “international English “speakers? In addition, as such, what do they teach? Answering these questions may lead to further understanding and improving ESOL teaching.

Keywords: TESOLLingua FrancaSociolinguisticsTeacher Training

Introduction

As a young traveler, almost two decades ago I have always found it awkward that I was better at explaining myself in English, to people in foreign non-English speaking countries than native speakers of English. Later on, while studying I understood that I was able to communicate better since I had the ability to shift and change the grammatical structures and vocabulary in a way that native speakers could not. Apparently, I was using ‘English as a Lingua Franca’ (ELF) without even being aware of it. So, if ELF is a natural accruing phenomenon, can it or should it be taught? And how can we actually study it?

The Evolvement of English into Lingua Franca

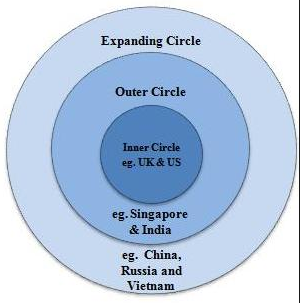

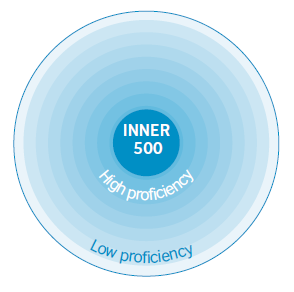

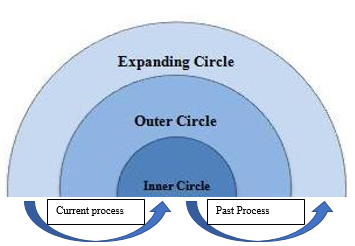

The term ‘English as a Lingua Franca’ (ELF) is referring to the use of English as a communicative tool of choice between people of different first languages (MacKenzie, 2014). English is considered to be the world’s LF or International Language (IL) today based on the number of people using it. Around 500 million people speak it as their L1 and a further 600 million people use it alongside their L1 as second language. At any given moment, there are about a billion-people studying it as a foreign language (Richards, 2015; Graddol 2006). Starting with the British colonial empire in the 19th century through the post-World War II American global dominance English became a dominant language in both political and economic international interactions (Graddol, 2006). Kachru (1990) named the phenomena ‘World Englishes’ and described it as expanding circles of language. Figure

Kachru objected his claim mainly because; speakers of the outer circles were not concerned with the ideas of ‘proper’ language use but rather with intelligibility. Through the lens of time, we can state that English today has become an international language / Lingua Franca (Richards, 2015). The technological revolution that started with the internet in 1995 and has expanded exponentially in the 21st century has brought forth tremendous sociological, economic and demographical changes. The large numbers of people migrating from place to place and the fact that the majority of the biggest world corporations are still US based and conduct their business in English for the time being place English in the position of the global communication tool for people from various places. One can observe that the internet holds almost twice as much pages in English than the relative number of Native English Speakers (NES) in the worlds’ population (Top Ten Internet Languages-World Internet Statistics, 2017). It is still unclear if English status will remain as such since data shows that there are other languages on the rise accompanied with the rise of new world super powers such as China and India, still for the near future English is the world’s Lingua Franca (Graddol, 2006; Friedrich, & Figueiredo, 2016).

The Native Speaker Problem

One of the problems relating to ELF is that it is a language that is not ‘owned’ by anyone in particular and therefore it is important to relate to the definitions of who is considered a native speaker of English. The fact that there are more Non-Native English Speakers today (NNES) than those who are considered to be NES has challenged linguists. The traditional approaches expressed by Randolph Quirk and other researchers regarded NESs as people who grew up in an inner circle country and acquired English as their L1. (Kachru, 1991; Medgyes, 1992, 2000). They claimed that no matter how much time people spent using the language even in an inner circle country, there will always be a barrier impossible to cross and therefore the would never be able to reach nativeness in its usage. Some would even go as far as to require certain ethnicity in order to be a NS (Moussu, 2006). However, when researchers checked TESOL teachers’ perspective they realized that apparently, many people in outer circle and the expanding circle countries do not agree with the definition. Some teachers perceive themselves and others perceive them to be NESs (Braine, 2010).

Davies (2003) concludes and claims that the only way to differentiate between NS and NNS is by their biography. What he meant was that it is possible for someone to achieve NS levels of use in the English language even if they were not born and raised in an ‘inner circle’ country. People can achieve that through long residence and use in an ‘inner circle’ country or by being exceptional students for example. Again, as with the case of Englishes before, it is an argument between what used to be and what is to be. One might wonder what is the difference between the development of a dialect in Texas away from the British Empire to the formation of Punjabi English in India (Trudgill, 2004). Perhaps the answer relates more to the political field than to the linguistic one. From a sociolinguistic perspective, one can assert that languages are formed within a community of practice and in a globalized world in which traditional communities are being replaced with ones that cross cultural, ethnic and lingual barriers by using ELF for communication it is time to redefine the circle model on a proficiency scale rather than a demographical one (

The Characteristics of Lingua Franca

Most irregularities in spoken ELF that do not coincide with the Standardized English (StE) relate to the parts of English grammar that differ from other natural languages. They can be roughly narrowed down to the following (Richards, 2015; MacKenzie, 2014; Harmer, 2015):

First notable feature is the non-use of the third person singular -s suffix. Some linguists consider it a natural development of language but most ELF speakers omit it sporadically unless it was learned in chunks of language such as: ‘it depends on, it makes sense, etc.

Another simplification of StE that happens in ELF is the regularization of the past form of verbs. Even though that is a process that can be noted happening in ENL as well it is still happening more noticeably in EFL. One can find the use of past forms such as:

Prepositions are also simplified in ELF. ‘in’ substitutes ‘at’ on many occasions relating to time and place and is becoming a generalized form. There is also over usage of prepositions such as:

Both ELF and ENL seem to develop a new pattern of prepositional verbs in which the preposition puts stronger emphasis such as:

address to (someone),phone to ,reject against , etc.

There is an apparent change in the use of articles. Perhaps the change stems from the arbitrariness of use in count and non-count nouns. Some dialects omit them completely and some use ‘some’ for plural and singular form.

The use of plurals also changes in ELF. There is frequent use of plurals with non-count nouns:

The use of the progressive form also differs with ELF users who use it with stative verbs and to describe habitual activities:

There is also a conflation between the present perfect and the past simple and the present simple. ELF speakers will use

ELF users tend to use the ‘to-infinitive’ form rather than the gerund. An ELF user will use:

chances to win, forget to do, whereas an ENL speaker will say:chances of winning, forget doing. Many ‘vernacular universals can be found in ELF:

The plural ‘

is ’: there is also many people.The use of ‘

would ’ and ‘would have ’ in hypothetical clauses (if the price would be the same ).Switching of the relative pronouns of ‘

who ’ and ‘which ’.Using ‘

isn’t it? ’ as a universal tag question.The extended use of certain verbs which have a wide variety of meaning:

do, have, take, make andput .

ELF speakers will often change sentence word order in particularly when using question:

Last noticeable feature is the stressing of the topic of a sentence by following it with a pronoun:

These differences they are important.

Is There Reciprocity Between ENL and ELF?

Perhaps the most interesting question regarding the ELF features shown above stems from the fact that almost all of them can be found in ENL language use (MacKenzie,2014). The question is if these features are a result of a natural evolvement of language or is there more to it? The theory of ‘World Englishes’ (Kachru, 1991) described the expansion of the English language from the NS inner circle towards the outer circle and the forming of new Englishes out of that process. But perhaps the change, as discussed before has more to it. Perhaps the evolvement of ELF and the fact that English interaction in a globalized post-modern world, in which new communities of speech are forming is creating a new English. The new language is not what Kachru described i.e. a variety but rather a new language that is forming and affecting all languages around it (Graddol, 2006; Facchinetti et al, 2010). Is this notion acceptable? Vivian Cook (Singelton et al, 2013 P: 27) focuses the attention on the target user. Unlike a native language, ELF is used for practical purposes whatever they may be and therefore it is used in a variety of occasions that cross traditional boundaries of various socio-economic variables. Furthermore, the theory of accommodation (MacKenzie,2014) claims that when people interact (in any language) their natural tendency will be to imitate the grammatical structures and vocabulary of other participants. It is logical to assume that when a ENL speaker interacts with an ELF speaker which is something that happens frequently in today’s world (Friedrich, Figueiredo, 2016), the accommodation will have to take part on the ENL side. Perhaps that is the reason that the same characteristics of ELF shown above manifest themselves within ENL communities, more in the spoken language than in the written one and at a slower rate (MacKenzie,2014). Does this change translate into the Teaching English for Speakers of Other Languages (TESOL) field?

Conclusion

Teaching Lingua Franca

The interaction between ELF and ENL creates a problem when it comes to the pedagogical question regarding its teaching. It is also an age-old debate regarding the actual form of language. Is it a set of structures and rules that construct meaning and enable communication or a living fluctuating entity that is measured only by its ability to form meaningful communication (Williams, 2000)? The former enables us to create a measurable pedagogical system and construct a Second Language Acquisition (SLA) theory while the latter leaves us ‘chasing our own tail’ trying to find coherence. The very nature of ELF stands at the basic answer and that is that traditional SLA theories cannot accommodate it and therefore there is no coherent way to ‘teach’ it (Singelton et al, 2013 P: 27). Even though there are references regarding ELF in teacher training guide books (Richards, 2015; Harmer, 2015) they are still not an integral part of the TESOL field (Sewell, 2012). Since we cannot completely ignore its influence on spoken language throughout the world and the English-speaking world as well, we have to ask ourselves what can be done in order to accommodate ELF within the TESOL practice? One option suggested is that the TESOL field will accept that the modern reality and especially the fluctuating rapidly changing nature of the internet (Friedrich, Figueiredo, 2016) requires of TESOL teachers aside from being aware of the nature of ELF to be also open to accommodate different expressions of language, even those who sidetrack from ENL and to learn to do that as part of their training (Sewell, 2012).

All of the above leads to a restrained ‘yes’ to answer the question raised in the title of this article. It is not certain that they need to ‘relearn’ a language they already know but it makes sense to think that they need to relearn how to teach it. That leaves us with an important question of how can we learn about the teaching of ELF? It is a difficult question because of ELF’s nature as was explained. While there is no absolute answer to this question, I do have a suggestion as to how we can research it and extract the data required for valid conclusions.

Native English Speaking Teachers (NESTs) – A Unique Research Population

Previously I presented the argument regarding the different approaches in defining the ENL speaker. For the purpose of this article, I will categories NESTs as people who acquired English as their L1 in one of the inner circles countries (Medgyes, 2000). Though it has nothing to do with the proficiency level or the environments perception of them as proficient English speakers (Davies, 2003; Moussu, 2006) it is relevant to the methodological assumption I wish to present. The emergence of English as ELF has expanded the TESOL profession and created numerous job opportunities for NEL speakers as TESOL teachers. The numbers are irrelevant to the assumption I wish to raise but the fact that they are spread worldwide does.

The NEST population was researched in many aspects regarding teacher-training and teaching but I wish to assert the claim that it holds valuable information regarding EFL. The uniqueness of this community lies in three key features that it holds and no one else does (Braine, 2010).

Its members are native speakers of English from inner circle countries.

They live in foreign non-English speaking countries and therefore, depending on the time spent there can speak another language and are susceptible for cross cultural influence.

Being teachers of language they possess a degree of linguistic awareness.

These three qualities make it possible for researchers do understand the intercultural effect on language. Since the population of NESTs is spread worldwide it might be possible to isolate characteristics of ELF that are not dependent on regional and local cultural and L1 effects. Furthermore, with regards to the TESOL profession we might be able to gain knowledge to the changes that their perception of the English language and teaching profession have undergone due to their ability to articulate that change in an ‘academic’ discourse.

Perhaps this kind of research may answer some of the questions raised here. It is clear though that there is a need for change in the way we teach English and the way we perceive it.

References

- Braine, G. (2010). Nonnative Speaker English Teachers: Research. Pedagogy and Professional Growth. London: Routledge.

- Crystal, D. (1995). Cambridge Encyclopedia of the English Language Cambridge University Press. Cambridge.

- Davies, A. (2003). The native speaker: Myth and reality (Vol. 38). Multilingual Matters, eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost, viewed 15 May 2017.

- Facchinetti, R., Crystal, D., & Seidlhofer, B. (2010). From international to local English - and back again. Bern: Peter Lang. , eBook Collection (EBSCOhost), EBSCOhost, viewed 23 May 2017.

- Friedrich, P., & de Figueiredo, E. H. D. (2016). The Sociolinguistics of Digital Englishes London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Graddol, D. (2006). English next (Vol. 62). London: British council.

- Harmer, J. (2015). The practice of English language teaching. Harlow: Pearson/Longman.

- Kachru, B. B. (1990). World Englishes and applied linguistics. World Englishes, 9(1), 3-20.

- Kachru, B. B. (1991). Liberation Linguistics and the Quirk Concern.: ERIC, EBSCOhost, viewed 15 May 2017.

- Kilickaya, F. (2009). World Englishes, English as an International Language and Applied Linguistics. English Language Teaching, 2(3), 35-38. ERIC, EBSCOhost, viewed 15 May 2017.

- MacKenzie, I. (2014). English as a lingua franca: Theorizing and teaching English. Routledge.

- Medgyes, P. (1992). Native or non-native: who's worth more? ELT Journal, 46(4), 340-349. doi:10.1093/elt/46.4.340

- Medgyes, P. (2000). Non-native speaker teacher. In , Routledge Encyclopedia of Language Teaching & Learning (pp. 444-446).: Education Source, EBSCOhost, 15 May 2017.

- Moussu, L. M. (2006). Native and Nonnative English-Speaking English as a Second Language Teachers: Student Attitudes, Teacher Self-Perceptions, and Intensive English Administrator Beliefs and Practices. Online Submission. ERIC, EBSCOhost, viewed 15 May 2017.

- Richards, J. C. (2015). Key issues in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

- Sewell, A. (2012). English as a lingua franca: ontology and ideology. ELT journal, 67(1), 3-10. ERIC, EBSCOhost, viewed 24 February 2017.

- Singleton, D., Fishman, J. A., Aronin, L., & Laoire, M. Ó. (Eds.). (2013). Current multilingualism: A new linguistic dispensation(Vol. 102). Walter de Gruyter.

- Top Ten Internet Languages - World Internet Statistics. (2017). Internetworldstats.com. Retrieved 27 May 2017, from http://www.internetworldstats.com/stats7.htm

- Trudgill, P. (2004). New-dialect formation: The inevitability of colonial Englishes. Oxford University Press, USA.

- Williams, M. (2000). Wittgenstein and Davidson on the Sociality of Language. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 30(3), 299-318., SPORTDiscus with Full Text, EBSCOhost, viewed 15 May 2017

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

28 June 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-040-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

41

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-889

Subjects

Teacher, teacher training, teaching skills, teaching techniques, special education, children with special needs

Cite this article as:

Badrian, N. (2018). Do Native English Speaking Tesol Teachers Need To Relearn English?. In V. Chis, & I. Albulescu (Eds.), Education, Reflection, Development – ERD 2017, vol 41. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 278-285). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.06.34