Abstract

This article considers the problems of young graduates seeking employment, problems made more acute by the discrepancy between supply and demand in the labour market: the shortage of qualified personnel for some sectors, of the economy and the lack of demand for young specialists with higher education degrees. The research question is intended to identify the plans and expectations of graduates from higher educational institutions on completion of their studies, assess the difficulties and possibilities of future employment, as well as the factors impeding employment according to specialization. The research is based on quantitative methodology: final year students from the arts disciplines of Tomsk high educational institutions were asked to fill in questionnaires (2017). Based on analysis of the data we identified inconsistencies and vagueness in the plans and intentions of graduates: on the one hand, respondents wanted to work according to their specialist profile, while on the other hand they intended to carry on studying, especially if this would provide them with a new profession that would lead to employment and be of more interest. One priority is the level of pay. It should be borne in mind that while studying students on Bachelor degrees are unable to define clearly why they would choose a particular profession, and many of them have only a patchy idea of working in a business. The graduate mindset is determined by uncertainty, it impacts on their self-esteem and becomes integral to their realistic possibilities and prospects in the labour market.

Keywords: Youth job marketthe employment expectations of graduatesreasons for continuing education

Introduction

In the modern world the individual is interested in achieving his/her own personal prosperity, based on the acquisition of skills essential for professional and personal advancement (Selyutin et al., 2016). The problems graduates from Russian higher educational institutions find in obtaining employment are made more acute by at least two factors. On the one hand, through objective factors such as the economic crisis, industrial decline, a shortage of work places in the labour market, and the low pay for a specialist starting out on his/her career path. The employment situation for young specialists is particularly difficult in towns based on a single industry, such as Yurga (Shabashev et al., 2016).

Thus, following on from our investigations we have established that 44.8% of those employed are working not according to their specialism, including 32.5% of respondents with higher education and 47.7% with secondary vocational education. (Students in vocational colleges on their future employment: ARPOR, 2015).

On the other hand, when offering work the modern employer also requires a certain set of skills: length of employment, professional experience, personal qualities such as even-temperedness, calmness under pressure, the ability to multitask, and personal commitment.

In today's world employers use an effective tool when hiring personnel: the competence model. A successful example of such a competence model could be that of personal factors, which includes 24 competences (Kiseleva & Anikina, 2015). Most graduates do not possess many such skills because of their age and social practices, and therefore are not competitive in the workplace. Furthermore, surveys show that students themselves increasingly express doubts that they can find work easily: only 42% of those graduates polled in Tomsk were sure that they would not have any problems in finding work. We can therefore see a discrepancy between the jobs market, its requirements and education, which sometimes does not meet the expectations of the market.

Researchers in the past also turned their attention to the role of education in working practices, noting the link between higher education and the worker’s labour productivity, leading to the greater commercial viability and competitiveness of the enterprise itself (Rozhdestvenskaia, 2017). In the 1960s other considerations were the link between education, the particular type of employment gained and the individual’s own job satisfaction. It was established that the level of education young people received did not correspond to the level of complexity of the work they were performing, and their profession similarly did not match their social standing, as a result job satisfaction waned and people began to look for other employment and professional possibilities. A positive consequence of this situation was the change in labour activity, the desire to overcome difficulties and adapt to new professional challenges, and the increased demand for higher education (Filippov, 1980).

Let us assume that both the management and the academic community of higher educational institutions need to adhere to principles of the marketing of relationships (Kiseleva et al., 2016a) to enhance the quality of students' education. Psychologists need to be recruited to draw up a psychological portrait of both potential and real students. The procedure for drawing up such a portrait is outlined in the literature (Kiseleva et al., 2016b). However, this requires some modification when taking into account what a higher educational institution actually does. In addition, there are good reasons to assess from time to time the level of interaction between students and academics and/or the higher educational institution itself. This would require a known universal model of interaction stages to be applied (Kiseleva et al., 2016c).

Today other problems are growing more topical: the misalignment of the system of education, the jobs market and similar discrepancies. These issues have been studied by both Russian and foreign writers. Much attention is given to the status of young people in the jobs market, and general characteristics of the youth jobs market are highlighted: the fluctuation in supply and demand, the low level of competitiveness of this age group, the increased risk of becoming redundant, or not being employed at all, hidden unemployment rates as a result of failure to register at the labour exchange, etc. (Bartlett, 2009).

Problem Statement

Problems of graduate employment and their status on the jobs market are studied by sociologists from various angles: the link between one's chosen specialism and future employment; the difficulties encountered (or may be encountered) by graduates when entering the jobs market; the adequacy of experience, knowledge and skills for employment.

Russian and Western sociologists have identified a number of factors that determine the unstable position of young people in the jobs market. External factors include the interaction of the jobs market and the educational system, failure to account of the demands of the jobs market, among others. Internal factors include the quality of specialist training, the range of competences, the lack of social experience among young people, their lack of social and professional focus, and the inconsistencies in their expectations of work.

Research Questions

Intentions after graduation

An individual encounters the jobs market twice: when choosing his/her profession and then when starting work. Both sociological data and actual practice (statistics) that employment is not necessarily connected with one’s chosen and obtained specialism in higher education. In the course of analysing the findings of our study we identified a discrepancy between the survey participants’ intentions and their assessment of future employment prospects. On the one hand, most (80%) of respondents would like to work according to their specialist profile, but at the same time every other person intended to continue education, with boys geared to continuing their studies to a greater degree than girls (58% and 44% respectively). One of the motives for this ‘thirst for knowledge’ among young men could be to insure themselves against military service.

The choice of educational trajectory is not so much focused on increasing knowledge and competences for a specialism already chosen. According to most of those polled, their future studies would more likely be connected with obtaining a new profession and studying something new: only 12& do not plan on changing their specialism. We also established that every third respondent is willing to pay for his/her re-training. As paradoxical as it may seem, but it is not only those respondents intending to continue their studies who want a new specialism, but also those who intend to work immediately after graduation (table

Intentions with regard to obtaining a new specialist profile are dependent on respondents’ conceptions of what it means to succeed in life. Every second respondent considers that the greatest achievement in life depend on knowledge and professionalism, whereas 38% believe that important connections are more important, and 15% believe that studying in a prestigious institute of higher education to gain a prestigious qualification is a key factor, although there are no observed gender differences in the assessment of reasons for continuing study.

Thus, one in two polled graduates intends to continue studying, though not according to the specialism obtained, but a new one, and the basic motive for further study is professionalization and the establishment of the right contacts and connections.

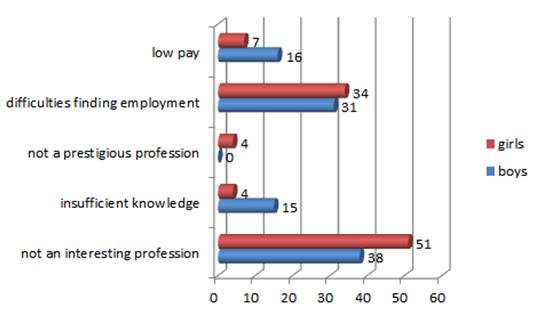

One third of those polled regardless of gender intend to work immediately after graduation, and the majority of them intend to work according to their professional profile. Those who do not intend to work according to their specialism give two basic reasons: ‘the profession is not an interesting one’, although more girls than boys specify this (51% and 38% respectively) and ‘difficulties finding work according to specialism (33%). There is a gender-dependent hierarchy of demotivational work factors for one’s obtained profession, which although repeated, differs in how the symbols are represented (fig.

The poll participants also have plans for so-called labour migration. Migration processes in today’s world are quite widespread: people move to receive an education, for work or for family considerations. 35% of respondents were positive about migration, though one in two in this group does not have any clear intentions in terms of social relocation. According to those polled, the basic reason are as follows: one in three either wants to try to find work abroad, or is not happy with the city landscape they live in (the city of Tomsk), 21% have doubts about employment, 13% refer to family circumstances, and 6% mention accommodation issues. Thus, attitudes towards migration among those polled are motivated more by socio-cultural and domestic conditions rather than an awareness of problems finding work.

Difficulties and opportunities in finding employment.

Young people today are in an unenviable situation when it comes to the jobs market: if in an earlier age there was the system of state allocation and guarantee of employment, now this system no longer exists and graduates have to find work themselves, and this is becoming more difficult because of ever-greater competition and the increased demands of employers.

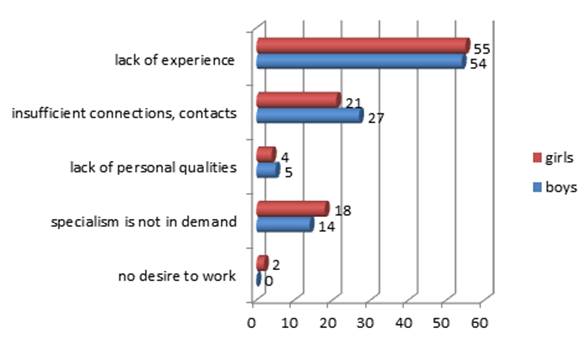

While seeking employment a potential employee may come across various difficulties, in the opinion of one in two of those polled (55%), the most serious of which is the lack of work experience. It was noted more than once that work experience is a significant competitive asset for the individual in the jobs market. Although most students today work while they are studying, among those polled 77% of boys and 60% of girls have (or had) a secondary job at the time of the survey, in 8 out of 10 cases these side jobs had no connection with their future profession. Other difficulties noted by the respondents include ‘insufficient connections and personal contacts’ (19%), ‘the lack of demand for this specialism in the jobs market’ (17%), ‘the lack of personal qualities’ (5%), and 2% of respondents admitted that they had no desire to work at all. Among those graduates wishing to start work immediately after graduation, boys in particular noted the need to have connections and personal contacts for successfully landing a job (fig.

The actions undertaken by graduates to find work are varied and specific: from interviews with employers, drawing up one’s résumé and making presentations to the company, to browsing websites and adverts. From the point of view of the respondents, 32% say that the most effective channels for finding employment for are ‘connections through friends and relatives’, and 26% assert ‘modern information resources’ (the Internet). Only one in ten poll participants relies on official and specialist structures (employment exchanges, employment agencies) as a successful channel for looking for work. The sense of self-worth of one in two respondents (58%) with regard to finding employment in the near future are diffuse and vague, with less than a third (27%) confident that they have a clear idea of where they will work and what they will do, and one in ten respondent admits that he/she has no concept of their own professional future.

If we talk about students, institutional structures could take it upon themselves to provide careers advice and assist with graduate employment. Those who took part in the survey have a definite expectation of help from the university: one in three expressed the desire to be allocated a specific job and place; 11% expect some training in how to find work. Most hope for various kinds of arrangements to be made, such as providing information on job vacancies (37%), or advising on the correct psychological approach (8%), or legal matters (6%).

Graduates a priori have the energy and the will to work, but the lack of work experience counts against them when looking for employment, as a result of which the search for a job can drag on for many long months. It is no surprise that most student opt for specialization, realizing beforehand that they will not use it in work, although there are some who still plan to move in that direction. Apart from experience, demotivating factors for professional work are the lack of interest in and unattractiveness of the specialization obtained, as well as the difficulties in finding employment. The jobs market today prioritizes working professions and technical specializations, and those who have a liberal arts background are faced with a negative outcome even before they start. This reality demonstrates that most graduates find work not according to their own specialization or desire, but as a result of a combination of circumstances.

Thus, the polled graduates clearly see their future employment as full of contradiction, as on the one hand they realize the importance of having work experience, yet on the other they do not have that experience, not so they intend to get it, in the specialization they have obtained. This is reflected in the respondents’ self-esteem and attitudes, and realistic possibilities in the jobs market. This dual situation is made worse because although every other respondent while studying at university was constantly or at least occasionally looking for work which he/she wanted to be engaged in after studying, half of those polled did not have any such plans and intended to continue their education, but studying for a different specialization.

The aspirations of future specialists

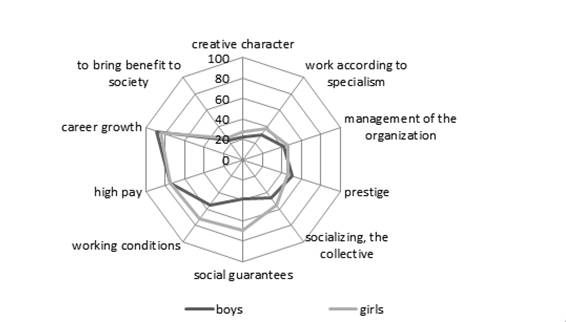

What demands do graduates have of their expected place of work? The gender-dependent hierarchy of the most important stimuli that motivated the respondents in looking for work is shown in figure

Both boys and girls are primarily attracted by the possibility of making a career and earning a respectable income. Girls also prioritize working conditions and the availability of social guarantees, whereas boys rate the prestige of the profession slightly higher. Researchers term this situation ‘egocentrism’, explaining it as young people being focused only on themselves, and doing everything for their own benefit and not for others (society as a whole). Referring to students’ value systems is not fortuitous here, as values are not simply an important behavioural motive, but also constitute the formative core of the individual as a whole and his/her activity. Traditionally, pragmatic considerations are of the utmost importance. However, a career demands of the individual a personal active stance and various losses (temporally, intellectually and, finally, physically). Moreover, survey participants do not pretend that they want work that is complex, or that demands a lot of qualifications and effort. An unequivocal ‘no’ was given to this by one in five respondents, two thirds expressed doubts and uncertainty, while only 10% of those polled wanted work to be challenging in terms of effort and qualifications.

One of the questions asked of the graduates concerned their conceptions of achieving success and how to do it. A large number (39%) identify success with the size of the pay packet, 28% with a stable place of work, 17% with self-development and creativity (boys particularly specified this category, 21% against 16% respectively), and 12% with freedom of choice. What can bring a young person success in life? Regardless of plans with respect to further study or employment, a significant portion of those polled consider that connections and the right people or professionalism (skills) are the primary factors in bringing success (table

The inference can be drawn that students in their choice of profession do not take into account the aptness of their chosen specialism for their personal interests, preferences, and predisposition for specific activity, and reckon first and foremost on the possibility of receiving social and economic dividends. We can make the point that a notable feature of life today is the increased desire of people to look for work that ensures a decent standard of living. The graduates polled are no exception. Young people have to a certain degree distorted concepts both of the jobs market and of their own possibilities of finding employment and trajectories of life.)

Purpose of the Study

An individual encounters the jobs market twice: when choosing his/her profession and then when starting work. Both sociological data and actual practice (statistics) that employment is not necessarily connected with one’s chosen and obtained specialism in higher education. In the course of analysing the findings of our study we identified a discrepancy between the survey participants’ intentions and their assessment of future employment prospects. On the one hand, most (80%) of respondents would like to work according to their specialist profile, but at the same time every other person intended to continue education, with boys geared to continuing their studies to a greater degree than girls (58% and 44% respectively).

Research Methods

This article presents the findings of research conducted in April-May 2017 among final-year students of liberal arts courses in the city of Tomsk. The research method chosen was questionnaires, with a cluster sampling of about 600 people. The main aim of the study was focused on identifying plans and expectations of Bachelor of Arts students with regard to future employment, their readiness to enter the jobs market, and other factors aiding or hindering employment according to specialist profile.

There are several approaches to understanding the jobs market. From the point of view of sociology this phenomenon is examined in terms of the individual's requirements as determined by values and norms prevalent in society, and are is not restricted to by the principle of rationality or maximum benefit. Employment is more commonly understood as the procedure for finding work which can be done either independently or through employment agencies.

With reference to the basic possibilities (or restrictions) of graduate employment, the following variables were highlighted: the plans and intentions of those taking part in the survey after graduation, demands for their future place of work and essential characteristics of their profession, assessment of the conditions that may hinder employment, and the role of the higher educational institution in this process.

Findings

Changes taking place have allowed a situation to develop wherein young people not only do not want to work according to their chosen specialism but also cannot do so. With time assessment of professions changes, and with it doubts begin to emerge about their professional choice. In the course of their higher education, students gather specific professional skills and at least give some thought to their future employment, but many factors inherent in today’s world create difficulties which impel them to ‘forget’ about professional intentions. On the one hand, guided by heightened expectations, students set themselves the aim of finding a highly-paid job with the possibility of career development and even comfortable living conditions, but, on the other hand, with an awareness of the difficulties of finding work, they are prepared to accept a vacancy which does not match their plans and which is not linked to the profession they have obtained.

Conclusion

Changes taking place have allowed a situation to develop wherein young people not only do not want to work according to their chosen specialism but also cannot do so. With time assessment of professions changes, and with it doubts begin to emerge about their professional choice. In the course of their higher education, students gather specific professional skills and at least give some thought to their future employment, but many factors inherent in today’s world create difficulties which impel them to ‘forget’ about professional intentions. On the one hand, guided by heightened expectations, students set themselves the aim of finding a highly-paid job with the possibility of career development and even comfortable living conditions, but, on the other hand, with an awareness of the difficulties of finding work, they are prepared to accept a vacancy which does not match their plans and which is not linked to the profession they have obtained.

Thus, a graduate’s disposition, according to which he/she build his/her own professional trajectory, is focused on acquiring symbolic rather than cultural capital. Symbolic capital mediates the perception, approaches to life and actions of a young person who presumes that this will allow him or her to attain results even in future employment. In other words, for the modern student of a Russian higher educational establishment what is important is not a specific specialization or profession (every one in two polled intends to continue their education), but symbolic characteristics acquire particular significance: prestige, certain mystical (distorted) skills, social connections, the size of the pay packet.

It is our opinion that for professional and personal focus the future young specialist must engage with three aspects. On the one hand, a higher educational establishment may conduct seminars and vocational training workshops for career planning (thus, for instance, in Tomsk Polytechnical University there is the ‘Centre for Employment Assistance and Career Development’, which is delivering the project ‘Labour Exchange’ for graduates); academics may engage in pastoral work with students and mentors may help future specialists to articulate their own models of successful competences and a clear concept of their future profession through trips to businesses, and organize meetings of potential employers with students for an open dialogue.

On the other hand, the active collaboration of future graduates with specialized structures designed to build a successful career is essential. The city of Tomsk boasts such organizations as the Centre for Employment of the Population, the Centre ‘Career Planning’, and the Centre for Vocational Orientation.

In these centres any applicant can undergo training according to his/her chosen professional direction and get advice from specialists in developing their own career (Ivankina et al., 2017).

We should also not forget about the personal participation of the individual in the choice of trajectory of professional development through self-study and active involvement in educational and practical projects in businesses and other organizations.

References

- Bartlett, W. (2009). The effectiveness of vocational education in promoting equity and occupational mobility amongst young people. Economic Annals, 54(180), 7–39.

- Filippov, F. R. (1980). Sociology of Education. Moscow, М: Znaniye.

- Ivankina, L., Trubchenko, T., Krukova, E., Shaidullina, A., Shaftelskaya, N., & Chernyak, V. (2017). The Use of Information and Communication Technologies by Elderly People (Sociological Survey Data). The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, 19, 235-242. DOI:dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.32

- Kiseleva, E. & Anikina, O. (2015). Modern Model of Competences of Personal Agents as Increase Factor of Clients’ Subjective Well-being. Procedia - Social and Behavioural Sciences, 166, 116-121. DOI:10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.12.494

- Kiseleva, E., Yeryomin, V., Filippova, T., & Yakimenko, E. (2016a). Personal Sales Focused on Improving the Psychological Wellbeing of Customers in the Context of Relationship Marketing. DOI:10.15405/epsbs.2016.02.36

- Kiseleva, E. S., Yeryomin, V. V., Yakimenko, E. V., Krakoveckaya, I. V., & Berkalov, S. V. (2016b). The psychological portrait as a tool to improve the subjective well-being of the client in the context of personal sales. SHS Web of Conferences, 28, 01122. DOI:10.1051/shsconf/20162801122

- Kiseleva, E., Yakimenko E., Sakharova E., Khmelkova N., & Krukova E. (2016c). The Universal Model of Stages of Customer Relationships as A Tool for Effective Managing with Personal Sales In the Context of Relationship Marketing. In Innovation Management and Education Excellence Vision 2020: from Regional Development Sustainability to Global Economic Growth (pp. 2821-2827). Seville: IBIMA. Retrieved June 19, 2017, from http://www.ibima.org/SPAIN2016/papers/eesk.html

- Rozhdestvenskaia E.M. (2017). Cognitive Capital and its Profitability. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, 613-616. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.82

- Selyutin, A., Kalasnikova, T., Danilova, N. & Frolova, N. (2016) Massification of the Higher Education as a Way to Individual Subjective Wellbeing. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, 19, 258-263. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.01.35

- Shabashev, V., Trifonov, V., Dobrycheva, I. (2016). Developing a Model for Machine Building Companies to Be Restructured in Russian Mono Company Towns as a Factor and a Condition of Well-Being. The European Proceedings of Social & Behavioural Sciences EpSBS, 346-351. DOI: dx.doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2016.02.45

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 April 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-037-2

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

38

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-509

Subjects

Social welfare, social services, personal health, public health

Cite this article as:

Dreval, A. N., Ivanova, V. S., Trubchenko, T. G., & Shaftelskaya, N. V. (2018). Expectations And Prospects For Professional And Personal Advancement Among Russian. In F. Casati, G. А. Barysheva, & W. Krieger (Eds.), Lifelong Wellbeing in the World - WELLSO 2017, vol 38. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 134-143). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.04.15