Features Of Professional Interpersonal Relationships: Organizational Cultures In Russia And United States

Abstract

This article discusses a current problem of the modern society that requires developing a scientific approach to research of interpersonal relationships in the professional world. There are different approaches to understanding how interpersonal relationships and satisfaction show up in the organization. The goal of this research is to deepen the concept of interpersonal relationships in the workplace, while describing their main components. Employees of Russian and US organizations who took part in the research were individual contributors, first line and middle managers in Russia (229 Russian speaking persons living and working in Russia) and in the United States (279 English speaking persons living and working in the United States) (N=508). The study was performed using: Interpersonal checklist by T. Leary (both “Real Me” and “Ideal Me” scales); projective methods of “Incomplete sentences” by J. Sacks and S. Levy (author’s version); content analysis, used for qualitative analysis of the results obtained with the projective methods. Data analysis included content analysis, analysis of the significance of differences (Chi-square, Mann-Whitney U), correlation analysis (Spearman’s rho), analysis of variance, one-factor ANOVA analysis, IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0. The results of our research demonstrated that both countries (using Russian and American organizational cultures as an example) have a unique and sufficiently strong cultural identity despite the multinational, multicultural, multilingual, multireligious qualities of each country. Moreover, in the present article, the authors are demonstrating that workplace interpersonal relationships exist and develop in the space defined by emotional attachment and the amount of social clarity between relationship partners.

Keywords: : Interpersonal relationshipsworkplace relationshipsatisfactionorganizational culture

Introduction

Social psychological literature and practice of organizational management often refer to the notions of “workplace relationships” (Reina, Reina, 2015; Bolman, Deal, 2003; Sias, 2009; Wagner, Muller, 2009) or “relationships in the workplace”. Also, one can often find such terms as “professional relationships” (Cross, Parker, 2004), “work relationships” and “business relationships” (Greenhalgh, 2001). Their translations into Russian (“delovye” (business), “rabochie” (work) and “proisvodstvennye” (industrial) relationships), respectively, bear connotations of the past historical periods in Russian mentality and have a certain component of assessment, while the “work relationships” term in the English language is completely neutral. Other versions of translations, such as “organizatsionnye” (organizational) or “korporativnye” (corporate) relations, not only do not clarify and specify the term, but also bring another meaning to the context. Given that, the authors suggest using the term “professional interpersonal relationships” to describe interpersonal relations that occur and develop in professional situations in organizations. Because each organization has its own unique culture, features of professional relationships are determined both by personalities of the relationship partners and by the context of organizational culture. Trust takes a significant place in the body of research of professional relationships. Trust is considered as a mechanism for creation of relationships (Gurieva, et al., 2016; Gibb, 1991); and as a system of values (Gurieva & Manichev, 2016; Tararukhina, Gurieva, 2015).

From all the models of interpersonal and professional relationships in organization that the authors studied in our research, they would like to outline the models and frameworks developed by many authors (Saunders 2011; Schutz, 1966, Fisher, Ury, 1991; Rosenberg, 2000; Greenhalgh, 2001; Patterson, Grenny, 2005; Hamilton, 2007; Wagner, Muller, 2009). The TORI model of Gibb J. consists of four discovering and creating processes that are indispensable to interpersonal relationships: Trusting-Being (T), Opening-Showing (O), Realizing-Actualizing (R), Interdepending-Interbeing (I). For Gibb, trust is the foundation for any relationship. Gibb J. believes that “being personal is a relationship” (Gibb, 1991, Р.11-24).

Having analyzed the research on interpersonal relationships in the workplace, the authors conclude that the notion of interpersonal relations is very important for the psychology as a science and as a practice of working with organizations, teams, professional groups, families, business partnerships etc.

Problem Statement

The concept of satisfaction in the workplace is usually discussed in the context of the satisfaction that employees get from their jobs, or client satisfaction with the organization’s product or service. Even though the concept of “satisfaction with relationships” is found in research studies on management, social psychology, and organizational development; this subject is far from being saturated. It is common knowledge that interpersonal relationships exist to meet the needs that a person cannot meet on his or her own. A person grows and develops due to relationships with others, and therefore needs them. Almost every conceptual model of motivation contains the idea of meeting individual’s needs. However, the notion of “satisfaction with interpersonal relations” has not been sufficiently developed yet, and there is a lack of methods and procedures for studying the essence of this phenomenon.

Research Questions

The subject of this research is social and psychological nuances of satisfaction with professional interpersonal relationships in different cultures. The object of this research is professional interpersonal relations in the organizations in Russia and the United States. The main hypothesis of this research is that the way interpersonal relations grow and develop in the workplace is determined by belonging to a specific organizational culture. Organizational cultures in Russia and in the USA were taken as an example for this study.

Purpose of the Study

The main objective of this work is to introduce the concept of “professional interpersonal relationship” to the research of organizations, study their components and put “satisfaction with interpersonal relations” in the context of different national organizational cultures. The authors performed this study within the framework of cross-cultural nuances of satisfaction with interpersonal relationships. The study was carried out in the organizations on the territory of Russia and the United States (Table

Research Methods

-

The interpersonal checklist by Leary T. (both “Real Me” and “Ideal Me” scales) to determine nuances of professional interpersonal relations of the respondents.

-

The projective method “Incomplete sentences” by Sacks J. and Levy S. (author’s version) to determine settings of the respondents for participants of the existing system of relations in an organization, as well as their content and direction.

-

Content analysis, which was used for qualitative analysis of the results obtained with the projective methods.

-

Quantitative methods (analysis of mean values, correlation analysis, contingency tables analysis, analysis of variance, one-factor ANOVA analysis, Mann-Whitney U criterion for independent selections, Wilcoxon W criterion for dependent selections, Pearson's chi-squared (χ2) criterion for comparison of nominal selections, Spearman’s r for detection of non-parametric correlations) were used for statistical solution of the certain research objectives.

Findings

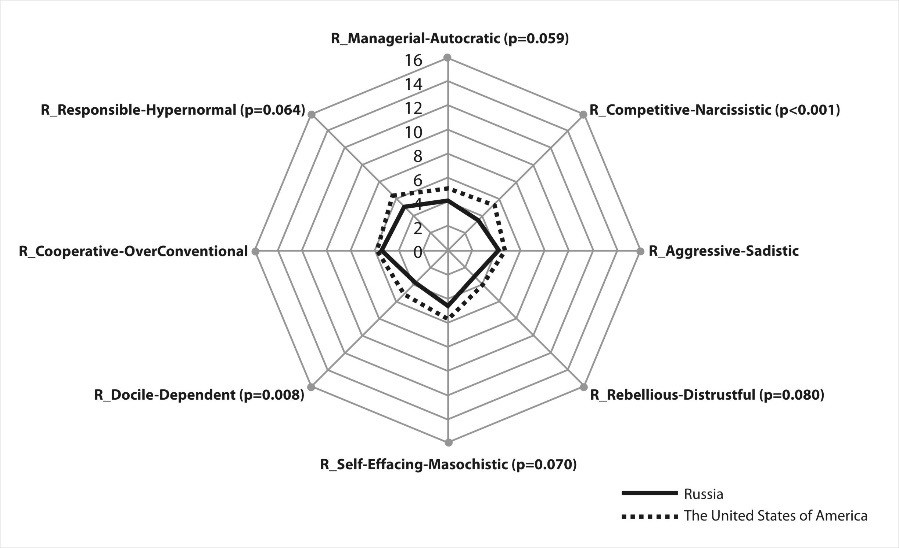

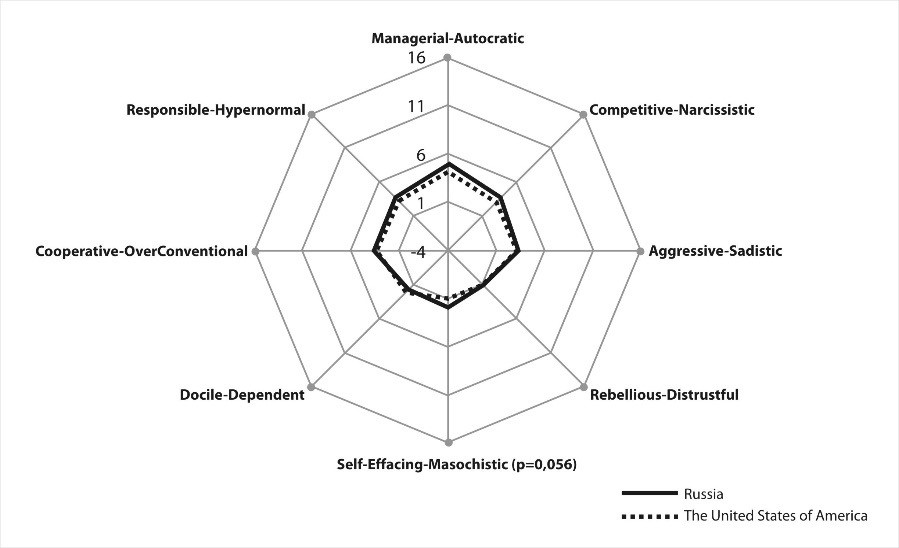

The authors studied cross-cultural differences in nuances of individual’s orientation in professional interpersonal relationships. For statistical significance analysis of the differences in eight parameters of Leary’s test, the authors used Mann-Whitney U criterion for independent selections. And for statistical significance analysis of differences between “Real Me” and “Ideal Me”, the authors used Wilcoxon W criterion for dependent selections. For these data, it is necessary to refer to Fig.

Statistically significant differences between data of the USA and Russian samples in the “Real Me” line were revealed in “Competitive-Narcissistic” (р<0.001) and “Docile-Dependent” (р=0.008) scales. Tendencies for differences were discovered in “Managerial-Autocratic” (р=0.059), “Rebellious-Distrustful” (р=0.080), “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” (р=0.070) and “Responsible-Hypernormal” (р=0.064) scales. These behavioral types are more pronounced by the Americans in all scales, although results for both countries appear predominantly in the first interval.

The “Ideal Me” category for both Russians and Americans has a tendency to differ on the “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” scale (р=0.056); among the Russians, there is also a tendency for more pronounced types of relationships in 6 out of 8 scales, while results for respondents from both countries appear predominantly in the zero interval. It is also worth mentioning that the aspiration for dominance in the Russian sample is more pronounced ideally than currently (factor is increased throughout the “Ideal Me” line in comparison with the “Real Me” category).

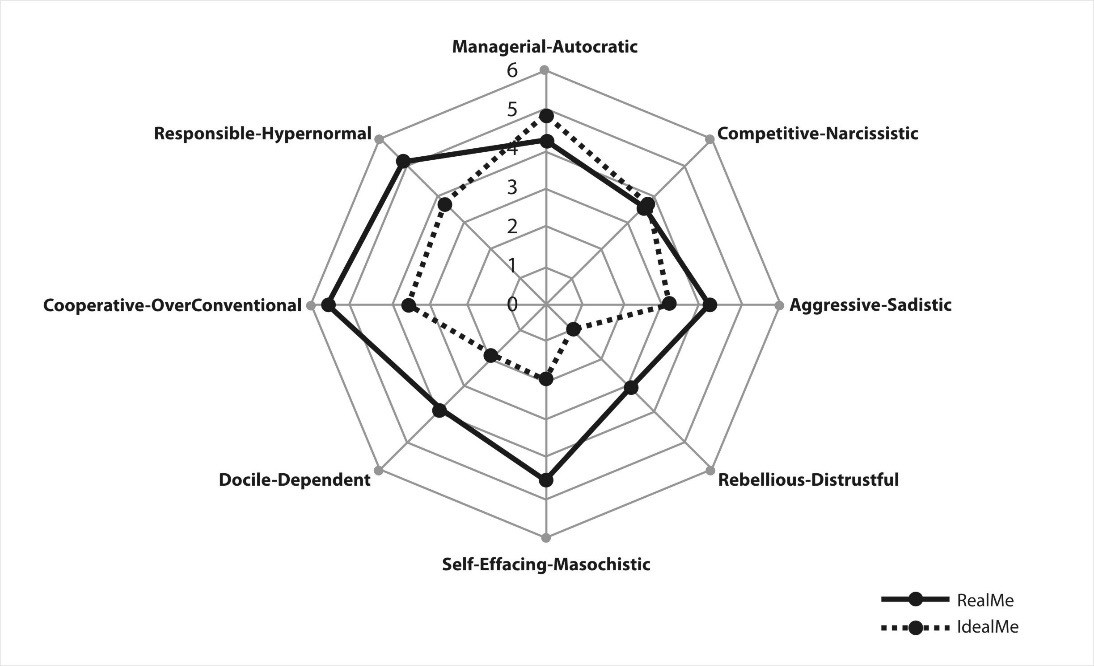

Statistically significant differences between the “Real Me” and the “Ideal Me” categories for the Russian sample were obtained using Wilcoxon W criterion for dependent samples in “Aggressive-Sadistic” (p=0.027), “Rebellious-Distrustful” (p<0.001), “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” (p<0.001), “Docile-Dependent” (p<0.001) and “Cooperative-Over Conventional” (p=0.002) scales. There is a tendency to differ between the samples in the “Managerial-Autocratic” scale (p=0.085), while “Responsible-Hypernormal” (p=0.145) and “Competitive-Narcissistic” (p=0.124) scales returned no significant differences.

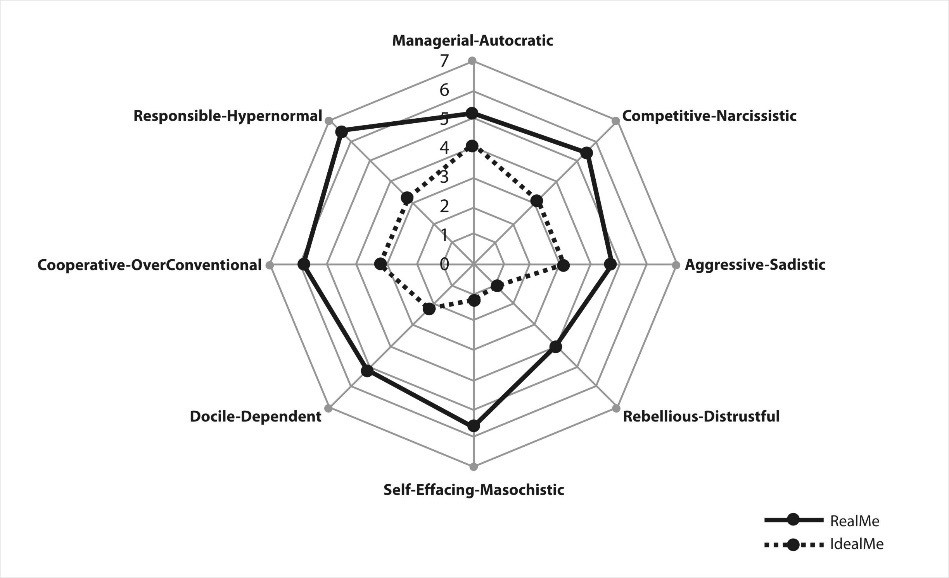

Statistically significant differences between the “Real Me” and the “Ideal Me” categories for the American sample were obtained in “Competitive-Narcissistic” (p<0.001), “Aggressive-Sadistic” (p=0.001), “Rebellious-Distrustful” (p<0.001), “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” (p<0.001), “Docile-Dependent” (p<0.001) “Cooperative-Over Conventional” (p=0.001) and “Responsible-Hypernormal” (p=0.001) scales. The authors have identified a tendency (p=0.077) in the “Managerial-Autocratic” scale.

Main differences between Russian and American samples were discovered in the “Real Me” category. These results allow us to argue that such features as self-respect, self-confidence, aspiration to compete with others, independence in acts and judgments, as well as aspiration to gain recognition and credibility in front of others, are more pronounced by employees of American organizations than by employees of Russian organizations. There is also a noticeable tendency in employees of American organizations to be more inclined to insist, to be skeptical, non-submissive and empathic than employees of Russian organizations.

Comparison of perceptions of the desired interpersonal relationships (the “Ideal Me” category) demonstrates that employees of Russian organizations would like to see themselves as more submissive, dependent and uncertain than American employees.

Diagrams in Fig.

Statistically significant differences between the “Real Me” and the “Ideal Me” categories in the Russian sample were obtained using Wilcoxon W criterion for dependent samples in “Aggressive-Sadistic” (p=0.027), “Rebellious-Distrustful” (p<0.001), “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” (p<0.001), “Docile-Dependent” (p<0.001) and “Cooperative-Over Conventional” (p=0.002) scales. They tend to differ in the “Managerial-Autocratic” scale (p=0.085), while “Responsible-Hypernormal” (p=0.145) and “Competitive-Narcissistic” (p=0.124) scales returned no significant differences.

Statistically significant differences between the “Real Me” and the “Ideal Me” categories for the American sample were obtained in “Competitive-Narcissistic” (p<0.001), “Aggressive-Sadistic” (p=0. 001), “Rebellious-Distrustful” (p<0.001), “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” (p<0.001), “Docile-Dependent” (p<0.001), “Cooperative-Over Conventional” (p=0.001) and “Responsible-Hypernormal” (p=0.001) scales. A tendency (p=0.077) was identified in the “Managerial-Autocratic” scale.

The difference in perception of real and desired interpersonal relationships of Russian employees can be observed in all scales except for the “Competitive-Narcissistic” scale. Additionally, Russians would like all their features of interpersonal relationships to be less pronounced, except for “Managerial-Autocratic” and “Competitive-Narcissistic”. The “Managerial-Autocratic” scale is more pronounced for Russian employees in the “Ideal Me”, while “Competitive-Narcissistic” is the same in “Real Me” and “Ideal Me”. American employees would like their ideal relationships to be less pronounced in all scales. Contrary to Russian employees, they would like to perceive themselves less dominant.

Therefore, results obtained using T. Leary’s checklist allow us to create psychological profiles of employees of American and Russian organizations reflecting specific nature of their professional interpersonal relationships and satisfaction with them. Correlation analysis has shown a great number of statistically significant connections among the factors obtained in all scales of T. Leary test in both categories (“Real Me” and “Ideal Me”) for respondents from Russia and the United States. For both Russian and American samples, the strongest correlations (r>=0.7) were obtained among the scales of the “Ideal Me” category. This observation allows us to conclude that the ideal perception of themselves in interpersonal relationships of both American and Russian respondents is more integrated than their perception of their real selves.

For the Russian sample, the strongest correlations in the “Real Me” category were obtained for the “Self-Effacing-Masochistic” scale. For the American sample, this feature of interpersonal relationships had the strongest correlation with self-esteem in the “Real Me” category: “Docile-Dependent”, “Responsible-Hyper normal” and “Cooperative-Over Conventional”. It is worth mentioning that we have observed a strong correlation between “Aggressive-Sadistic” and “Rebellious-Distrustful” scales, in perceptions of employees in American organizations.

Consequently, one can postulate a certain divergence between real and ideal perceptions of self-image among respondents in both Russian and American companies, which may cause employees interpersonal conflicts. In addition, American respondents ideally would like to decrease levels of all scales of their perception of their real self, and Russian respondents ideally would like to decrease pronouncement in 6 out of 8 scales. The authors can conclude that there is a desire to n aspiration to decrease, “mute” expression of emotions in professional interpersonal relationships in both samples. For employees of American companies, this tendency is more clearly pronounced and that, together with the results of correlation analysis, shows that the employees of American companies are more inclined to the practical and rational aspects of professional interpersonal relationships than Russians. The Russian sample dis not demonstrate a clear perception of their ideal interpersonal relationships; the authors observed a tendency to demonstrate more dominance and to maintain the current level of independency.

Conclusion

As a result of the performed and discussed above cross-cultural research, the authors are making the following conclusions:

Results obtained with method of “Interpersonal checklist” by T. Leary demonstrated the differences in the perceptions of “Real Me” and “Ideal Me”, which reflects satisfaction with professional interpersonal relations among employees of the Russian and the American organizations. The authors attribute this fact to special features of organizational culture unique to the companies.

Respondents in both countries demonstrate more pronounced elements of “Ideal Me” as less pronounced, more integrated (interrelated) than the scales of “Real Me”. Employees of American companies demonstrate a desire to decrease intensity of all scales of professional interpersonal relationships. The Russian sample demonstrated a slightly more controversial tendency, by demonstrating a desire to increase dominance and preserve the existing level of independency.

One may consider the “submission” aspect as a strategic attribute of the “Real Me” among the employees of organizations in both Russia and the United States; in conjunction with other data it may signal a kind of social inactivity in the employees of both countries, which may correlate with the studies demonstrating the epidemic of low employee engagement. At the same time, one may consider the orientation to an increased practicality in interpersonal relationships to be a distinctive feature of the American employees.

The results of our research demonstrate that professional interpersonal relations in the Russian and the American organizations are determined by unique and sufficiently strong cultural identities. These identities are strong despite multinational, multicultural, multilinguistic, and multireligious diversity that is inherent in each national culture.

The amount of research in the field of professional relations should be on the rise not only due to economic reasons, but also due to the significance of social contacts, the fundamental human needs for belonging, connection with others that are even more important at the current stage of the development of our civilization. The contemporary socio-economic situation inevitably leads to the continuous increase of a number of contacts established by an average person. The ability to effectively (i.e. quickly and with satisfaction for both parties) establish, sustain and develop relationships, manage conflict and stressful situations, as well as to help others people to manage them, is becoming an increasingly more important competence of a successful person. Continuing and enhancing research in this field is a vital objective of contemporary social psychology.

References

- Bolman, L. G., Deal, T. E. (2003). Reframing Organizations. 3rd ed. CA, Jossey-Bass.

- Cross, R., Parker, A. (2004). The Hidden Power of Social Networks. Boston, Mass: Harvard Business Press.

- Fisher, R., Ury, W. (1991). Getting to Yes. Negotiating Agreement without Giving in. NY, Penguin Books.

- Gibb, J. (1991). Trust. A New Vision of Human Relationships for Business, Education, Family, and Personal Living. CA, Newcastle Publishing.

- Greenhalgh, L. (2001). Managing Strategic Relationships. New York, NY: The Free Press.

- Gurieva, S., Borisova, M., Takeyasu, Kawabata et al. (2016). Trust as a Mechanism of Social Regulation in the Modern Youth's Behavior. American Journal of Applied Sciences, 13, 1, 100-110. http://thescipub.com/PDF/ajassp.2016.100.110.pdf

- Gurieva, S., Manichev, S. (2016). Values and Hardiness: Entrepreneurs of Former Soviet Countries. Indian Journal of Science and Technology, 9 (46), 333-342. DOI: 10.17485/ijst/2016/v9i46/107510.

- Hamilton, V. (2007). Human Relations. The Art and Science of Building Effective Relationships. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Patterson, K., Grenny, J., McMillan, R., Switzler, A. (2005). Crucial Confrontations. Part 2. McGraw-Hill.

- Reina, D., Reina, M. (2015). Trust and Betrayal in the Workplace: Building Effective Relationships in Your Organization. CA, Berrett-Koehler,

- Rosenberg, M. (2000). Nonviolent Communication. Encinitas, CA: Puddle Dancer Press.

- Saunders, H. (2011). Sustained Dialogue in Conflicts: Transformation and Change. NY, Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schutz, W. (1966). The interpersonal underworld. Palo Alto, Science and Behavior Books.

- Sias, P. M. (2009). Organizing Relationships: Traditional and Emerging Perspectives on Workplace Relationships. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Tararukhina, O., Gurieva, S. D. (2015). Socio-Psychological Model of Interpersonal Relationships in Organization Contemporary Research of Social Problems, 1 (21), 26-40. http://sisp.nkras.ru/p-ru/issues/2015.html ISSN 2077-1770

- Wagner, R., Muller, G. (2009). Power of 2. How to Make the Most of Your Partnership at Work and in Life. NY: Gallup Press.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

19 February 2018

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-034-1

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

35

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1452

Subjects

Business, business innovation, science, technology, society, organizational behaviour, behaviour behaviour

Cite this article as:

Gurieva, S. D., Tararukhina, O. V., Chiker, V. A., & Yanicheva, T. G. (2018). Features Of Professional Interpersonal Relationships: Organizational Cultures In Russia And United States. In I. B. Ardashkin, N. V. Martyushev, S. V. Klyagin, E. V. Barkova, A. R. Massalimova, & V. N. Syrov (Eds.), Research Paradigms Transformation in Social Sciences, vol 35. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 436-444). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2018.02.51