Abstract

For long researchers have been making a case in favor of formative assessment or ‘assessment for learning’ (Williams 2009) against summative assessment or ‘assessment of learning’ (Isabwe, 2012). In our earlier work (

Keywords: Formative assessmentstudents’ perceptionsfeedbackhigher educationPakistan

Introduction

Teaching and learning is an active and reflective process where instruction and assessment go hand-in-hand. Just like instructional strategies, various types and forms of assessment are not only in practice at all levels of education but are also of interest to educationists, policy makers and researchers. While conceptually the concept of formative assessment/ assessment for learning sounds more plausible, empirically the research field is branched; on one hand are the followers of Paul Black and Dylan Wiliam’s seminal work (Black & William, 1998). The latter for long have been advocating formative assessment or ‘assessment for learning’ (William, 2009; Black, Harrison, Lee, Marshall & William, 2004; Black & William, 2003). On the other hand are those who favor summative assessment or ‘assessment of learning’ (Isabwe, 2012; Clark, 2011; Fook & Sidhu, 2010). Quite a few are in between who look at how the two approaches together can facilitate or hinder students’ learning (Kennedy, Chan, Fok, & Yu, 2008; Saltmarsh & Saltmarsh, 2008; Harlen, 2006; 2005).

The definition of formative assessment, for the purposes of our research, is taken from Minstrell, Anderson & Li (2011) who state; “Classroom assessment becomes

It is important to state that like Limniou & Smith, (2014), we also believe that formative assessment is a process whereby students “reflect on their own learning and understand what has been developed, omitted or improved” (p. 210), therefore, their perspective may be helpful in evaluating the utility of feedback practice for learning. However, while we recognize that formative feedback is a communication between two parties- instructor (s) and learner (s), the primary focus of our research is limited to the views of ‘learners’ only; we explored the students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward the feedback they hard eceived from their instructors in the institutions of higher learning in Pakistan during the study period. We purposefully selected a sub-sample of 32 students with Median score = 22 and above from the sample of our previous study. The views of these students were explored with the help of a semi structured questionnaire and a series of focus group discussions. The emerging themes were coded and analyzed for patterns.

The role of feedback in academic setting

Feedback as a positive influence

Formative feedback is an integral part of teaching and learning in general and of formative assessment in particular. A large body of research exists that highlights the value of feedback in academic setup. For instance, one of the contributions of feedback to learning is that it enhances students’ academic achievement and motivation (Akkuzu, 2014;; Clark, 2012; Cauley & McMillan, 2010; Wang and Wu, 2008; Yorke, 2003). An additional expression of its facilitative role is that feedback clarifies students’ misconceptions (Searle, 2013) and reconstructs their knowledge and/or skills (Hattie, 2012; Hattie & Timperely, 2007). The most often cited meta-analyses by Black & William (1998) and Hattie (1987), also draw attention to yet another role of feedback, i.e., it improves the quality of students’ academic outcomes. A host of recent research studies further reinforce the effectiveness of feedback for teaching and learning (Lysaght, 2015; Harshman & Yezierski, 2015; Tay, 2015; among others).

Students’ perspective on feedback

Students’ views on and usage of feedback as a research topic has been very fertile and germane across disciplines and across education levels (Forsythe & Johnson, 2017; Pitt & Norton, 2017; Cookson, 2016; Jackson & Marks, 2015; Ludvigsen, Krumsvik & Furnes, 2015; Roy, 2015; just to name a few). In a two-part research study Lizzio & Wilson (2008) asked 57 and 277 students respectively to evaluate the written feedback they had received for different assessment pieces to distinguish the helping and hindering comments. Based on their ranking and the factor analysis of responses, the most effective feedback was the ‘developmental feedback’ which had the following characteristics; ”Transferability, Identifying goals, Suggesting strategies and Engaging content” (p.268). The contribution of this study to the field is two-fold;

It has highlighted the ‘subjective’ nature of the evaluation criteria that students used for identifying the effectiveness of written feedback; how they defined ‘effectiveness’ falls in the ‘subjective’ domain and thus may be unique to the context it was studied in.

It has also identified an underlying structure through statistical method of Factor analysis which brings out the ‘objective’ dimension of students’ comments on the subject. This quantification of students’ responses renders the data more amenable to standardization and wider applicability.

Similarly, Murphy and Cornell (2010) in their study had a focus group discussion with 38 undergraduates, from three institutions in UK, on their perceptions of the quality and quantity of feedback. Their thematic analysis revealed students’ emphasis on, relevance, specificity, timeliness and clarity as the mark of quality (p.50). Working in the same direction, Hemingway (2011) and Glasson (2009) have added positivity among the major attributes of facilitative feedback from students’ perspective.

One of the essential (and common) elements of the research studies on feedback is that almost all of them underscore the positive role of feedback in students’ learning. In this connection these studies suggest an array of students’ views on feedback, i.e., what they considered was good, bad and/ or effective feedback. The common contribution of these studies (and others in the field) is the identification of a host of factors that affect students’ views on feedback. These factors include academic as well as non-academic factors. Moreover, most of the studies have used qualitative methods of research as these offer more opportunities for probing and extended discussions. Both these inputs were extremely relevant to our research; the first helped us in categorizing the content of data while the other pointed out the appropriate methods of data collection. Keeping in mind the context of our research we identified the appropriate spheres for data collection which were then used for preparing an Interview Guide for conducting semi-structured interviews and focus group discussions.

One of the most visible limitations of the body of literature cited above on feedback is that students appear as passive recipients of the feedback in general and in the case of written feedback in particular. Though one may be able to discern it from their discussions, most of the studies explicitly fall short of bringing out the role of students as active ‘players’ in the utilization of feedback. While we do not intend to deny the contribution and consequence of formative feedback, the fact remains that feedback is only a tool; how it is used and to what end will vary from individual to individual thus making a difference to the outcome or the desired impact. By positioning individual learner in relation to feedback, Price, Handley, Millar and O’Donovan (2010) draw attention to the fact that the effectiveness of feedback is situated in the interaction of individuals with it and how they decide to use it is a personal choice. The centrality of students’ choices and actions in relation to the use of feedback equates them with ‘rational consumers’ and this is the theoretical stance of our research.

Students as consumers of feedback

The work by Higgins, Hartley and Skelton (2002) on formative feedback, lends support to the idea of students being rational consumers of feedback. Their ‘Conscientious Consumer’[s] are those students who are more interested in understanding the subject rather than just completing a task and getting final grades. Students as conscientious consumers are; “

Students are consumers of feedback

Students themselves are catalysts for change in their learning (Price, Handley, Millar and O’Donovan, 2010)

The effectiveness of feedback is situated in students’ interaction with it (ibid)

How they decide to use feedback is a personal choice (Sanchez & Dunworth, 2015)

Students’ perception of the utility or futility of feedback will determine the ultimate use of it (ibid).

The theoretical and conceptual framework of the study

The basic premise of our research is that being a consumer, students can decide what to do with the product in hand which for our research is ‘the feedback they received from their instructor on a specific piece of assignment for formative assessment.’ As consumers they have their choices and preferences based on their views of the product; how important is an instructors feedback will shape their perceptions of the utility or futility of the feedback and will determine their attitude towards the usage of the feedback and the way they interact with it will result in the attainment (or otherwise) of the desired outcome. Our specific research question was; what are the students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward the feedback they receive from their instructors in the institutions of higher learning in Pakistan?

Problem Statement

In our earlier work on assessment, we compared students’ results of written assignments and quizzes that were assessed through formative and summative assessment techniques. All our results for summative assessment were statistically significant but non-significant for formative assessment. Our findings revealed that students generally put more effort into tasks for summative assessment (Qureshi, Zahoor and Zahoor, 2017). What stops them from putting equal effort, if not more, into tasks for formative assessment is a question worth exploring. The purpose of the current research was to extend our work to reconnect with same students in order to explore their perspective on formative assessment.

Research Questions

What are the students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward the feedback they receive from their instructors in the institutions of higher learning in Pakistan?

Purpose of the Study

The purpose of the study is to explore the perspective of students on formative assessment

Research Methods

Sampling and Participants

In order to reconnect with our earlier study published in 2017, a brief sketch of sample details is presented. For that research an institution of higher learning was the research site. It was chosen purposefully and the study period was two consecutive semesters in 2011. The sample comprised of two intact groups of 60 student- teachers who were enrolled in two research methodology courses (for details see Qureshi, Zahoor and Zahoor 2017 in the reference section). For the present study, we reconnected with a sub-sample of 32 student-teachers from the above study in January 2013 as for all their assessed pieces, these students had received feedback which for our purposes was defined as, “information provided by an agent [the instructor] … regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding” (Hattie and Timperley, 2007:81) in either form, verbal or written. They had received; general feedback as a whole class, specific written feedback individually and one-to-one oral feedback as and when sought by them. The, sample, therefore, was suitable for exploring the views and attitudes toward formative feedback as a key instrument of formative assessment.

The single selection criterion for the participants was extremely low scores on assignment and quiz assessed with token grades but high scorers on summative assessment (Median score = 22 +). The token grade indicated their performance but was not part of the final official grade sheets. The timing of the data collection was also done purposively as the students had completed all their degree requirements, were under no pressure for time and were more ‘open’ to answer freely. All of them gave their consent to be interviewed individually but only 24 students were willing to share their views through a series of focus group discussions.

Tools for and methods of data collection

Interview Guide

We prepared an interview guide with the help of open ended questions culled from literature available on the subject. For exploring students views and use of the ‘feedback’ provided to them by their instructors on two specific pieces of assessment, i.e., quiz and written assignment, for a course in research methodology, we interviewed 32 students for a duration of 40-60 minutes and asked them to respond to a set of three open ended statements;

I did not use the instructor’s comments because-----.

The responses would reveal personal choices and reasons for the actions taken or not taken. It would make the ‘I’ more visible as an active player by bringing out ‘I am responsible for my decision’ kind of attitude.

I could not use the instructor’s comments because-----.

The responses would exhibit ‘fault finding /blame shifting’ behavior and ‘I’ as a passive victim of the larger forces; ‘It is not my fault’ kind of attitude.

I would like to use the instructor’s comments in future for-----------

The responses would give clues of the students’ futuristic vision of the gains from their interaction with the feedback they had received. The responses would not only show their views on future utilization of these gains for their personal and career advancement plans but would also be useful for triangulation of the data from Statement 1 above and the information obtained from focus group discussions.

Checklist for Focus Group Discussion (FDG)

For focus group discussions, a checklist of the topics was prepared from multiple sources including, but not restricted to, other research studies on the topic, formal discussions and informal conversations with colleagues, and last but not least, personal observations and experiences of being on both sides of the fence. The final consensus among the team members produced the following questions;

Does feedback make a difference in the overall scheme of students’ learning?

Why should instructors give or be asked to give feedback?

What are the preferred alternatives?

What other mechanisms could be suggested?

Three groups, comprising of 8 students plus a moderator and a note-taker, were formed and the questions were deliberated upon in two rounds. In the first round, questions 1&2 and in the second round questions 3&4 respectively, were discussed by all groups, in three separate rooms, at the same time and place. The duration of the discussions varied between 90-120 minutes. In so doing, we explored the views and attitude of graduate students through 32 individual interviews and six focus group discussions. The emerging themes from both sources were coded and analyzed for patterns.

Findings

The purpose of our research was to explore students’ perceptions and attitudes toward feedback in the institutions of higher learning in Pakistan. For this reason we posed the following research question; what are the students’ perceptions of and attitudes toward the feedback they receive from their instructors in the institutions of higher learning in Pakistan? In order to address this question we selected a sample of 32 students who had received feedback from their instructors on assignments for formative assessment. These students were interviewed with an Interview Guide specifically developed for the purpose. 24 out of these also participated in focus group discussions and voiced their opinions.

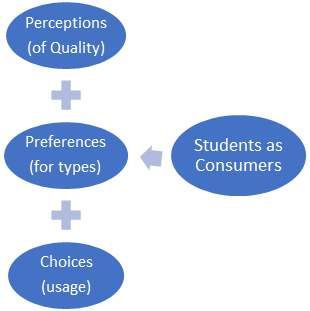

As stated earlier, the premise of our research is that as individuals, students are rational consumers of feedback with perceptions, preferences and choices. Figure

Students Choices

As consumers, students have a choice to be selective- to use or not to use the feedback they had received from their instructors. Our purpose was to unravel the ‘why’ of these choices. The ‘usage’ fell into two categories of close split in numbers; by personal decision and under duress.

Free Personal decisions

The students who decided not to spend ‘too much’ time on incorporating their instructors feedback were reluctance to invest their time and energy in engaging with feedback because of the ‘invisibility of their efforts’ towards incorporating the feedback;

The amount of time I spent in working on the feedback I wish my instructors could see and take notice of the efforts I had made (R23, S1 (S denotes the Source of data for thematic analysis; S1 and S2 correspond to data from interviews and FDGs respectively. ) )

I worked only on those comments which did not take much time because putting too much effort means wasting a lot of time…yes ‘wasting’ because nobody can see it...so where does it go…just vanishes in thin air. (R4, S1)

Students, while owning their actions, also included ‘lack of appreciation’ by Instructors as a reason for their inaction;

Another major reason for not interacting with feedback was that it required more ‘intensive engagement with academic readings’ than the students had or were willing to have;

I spent a lot of time in reading and re-reading the assigned material but the feedback I received said that I had not understood the main concepts. I said to myself “if that is the case then let it be. I am not going to concentrate on it more than I have already done” (R15, S1)

I skim through the assigned readings and I know that if I do not understand something at that time then there is no point in going over it again. I know my habits, so why waste time in working on feedback that requires me to do this? (R30, S1).

A different but relevant issue relates to the medium of instruction and the ‘language’ of the readings. In Pakistan English is the language of teaching and learning for higher education institutions. The context of the students’ daily lives is a mosaic of multiple languages with different syntax and structures. The difference between the languages of learning and living contexts exacerbates the difficulties of engaging with academic readings;

I have to read more than once just to understand the language. Then read again to comprehend the jargons…yet the feedback says ‘superficial analysis’ [mimics Instructor] makes me feel like I have been wasting my time (R25, S1)

At times I think if the readings were not in English my performance on assignments would have been a lot better … even working on the feedback would have been much easier (R32, S1).

The stuff [reading] is in English which in itself is time-consuming. Working on assignments also takes time so when the feedback says I need to re-engage with readings in order to ‘read between the lines’ then I feel like banging my head against the wall (R20, S1).

The issue of language and its impact on academic performance (and formative feedback by implications) was a recurring theme in interviews and FGDs. Moreover, feedback, as an exchange of ideas, takes place in a context where the medium of instruction is English and neither learner nor instructor (generally) is a native speaker of English. On top of it, the complex and multidimensional nature of the academic language is another challenge non-native speakers of a language have to surmount.

Decisions under duress

Majority of the students were of the view that they did not use the feedback because ‘it was difficult to understand’;

Instructor’s feedback was handwritten…the writing was like medical doctors, you know [laughs] …very difficult to read. [Makes a face] what then of understanding [with a shrug of shoulders] little wonder I was unable to work on it (R10, S1)

The quality of the feedback was not good. The comments were too general and were written all over the paper. Which comment belonged where was not clear. It was difficult for me to locate the gap in my arguments that was being pointed out. (R1, S1).

Most of the comments are vague. I really had to spend considerable time in ‘decoding’ the intended message. If there were really a message then sorry, both its meaning and significance were lost (R22, S1)

Another point of concern was that Instructors expected too much from students;

They do not realize that theirs is not the only course we are taking. They ought to understand that we cannot spend a whole lot of time concentrating just on one piece of assignment for one course which they teach (R18, S1).

I would have spent at least half a semester on this assignment and the related feedback if I did not have to divide my time and energy among all the courses I was taking. Now when I look back I seriously think that Instructors are responsible for creating undue stress in our lives (R8, S1).

Research studies on feedback have come to a common understanding that it is a dialogic process; a give and take activity that involves at least two agents- Instructor and student. Although the focus of our research was on the role of ‘learners’ in the process, our participants would invariably bring in the views of the other agent in telling their own story. Initially when the participants were explaining why they decided not to engage with the feedback, their locus of control was ‘internal’ as they were locating the causes within their own behavior (Hill, 2016). Their explanations did not hold any other stakeholder responsible. With the assured way of thinking they believed that they themselves were in control of their performance (Hill, 2016). However, gradually their explanations shifted toward ‘external’ locus of control when they started explaining why they could not engage with the feedback; the reasons they gave involved external forces which they thought were in control (Hill, 2016).

Students Perceptions

Students were not only aware of the role of feedback in improving the quality of learning outcomes but were also attentive to the ‘quality’ of feedback they had received. Their perceptions varied widely;

For me quality of a feedback lies in its ‘understandability.’ What value a set of comments written in excellent English would add to my learning if I am unable to understand even half of it? (S2)

I go for simplicity of the language; an effective feedback uses simple language and plain sentences for connecting with a student like me rather than scaring me with big words and fancy language. I do not care if it is in King’s English, it is not my language anyway (S2).

A good feedback is detailed… it pin points exactly what is wrong and how to fix it…it gives clear directions… is not vague (S2).

Most of the perceptions of the quality of feedback, identified by students in our sample, were similar to the ones described by Murphy & Cornell (2010). Contrary to the observations of Hemingway (2011) and Glasson (2009), none of the students in our sample directly mentioned ‘positivity’ among the quality indicators of a good feedback.

As far as the future utilization of the gains from formative feedback was concerned, none of the students denied the ‘potential’ role of the formative feedback in their personal and career advancement in future. One of the participants commented that the benefits of formative feedback generally materialized very late even in the span of campus life. To the same effect, an excerpt from an interview is given below for two reasons; not only is it explicit and unique but also vivid in summing up the wide-ranging position of feedback in that respect, and represents the majority of students’ views in our sample as well;

Being ruralite, I compare the benefits of formative feedback with growing of sugarcane which is the main crop of my area. It takes 12 to 16 months in getting ready for harvesting but everybody works hard for it because it brings in cash which not only sustains the farming families but is also important for the local economy (R9, S1).

Students Preferences

As consumers students also have preferences for the kind of feedback they would like better (and are likely to use). The first category that emerged for comparison was Oral vs. written feedback. Majority of the students liked the oral feedback which was given mostly in local language.

Oral vs. written feedback

I like oral feedback because I can understand it better (R13, S1)

Oral feedback is better because it does not hurt much [general laughter] we can counter argue, ask probing questions and can have extended discussion in our own language (S2).

When giving feedback orally, Instructors usually use a mixture of English and local language. I feel more comfortable with that kind of communication. (R6, S1).

While the majority clearly indicated their liking for oral feedback, they also had concerns about the practicality of its usage;

Oral feedback is easy to understand but then translating the suggestions or ideas is difficult (S2)

Getting feedback in local language [oral] sounds great, incorporating it in English [pause] too much is lost in translation, a lot is gained in frustration…improvement?, not worth it (S2)

Even if they did not prefer written feedback, students were aware of the practical advantages it offered;

Written feedback is more formal and structured. One can recycle some of the vocabulary for improving one’s own work (S2)

Written feedback with track changes is more effective and less time consuming as it is detailed and precise (S2)

Majority of the students preferring written feedback emphasized their partiality for typed/electronic feedback just like the 70% of the students in Mulliner & Tucker (2017) study but unlike the majority of students in Edeiken-Cooperman & Berenato’ (2014) study.

Corrective/ direct vs. indirect feedback

Almost all students preferred corrective feedback;

A good feedback ‘tells’ what is wrong, where and how to correct it. It helps students by correcting mistakes, not leaving them unsure of how to do it (S2)

What is the point of indicating your errors and not correcting them? An Instructor should provide solutions not suggestions (S2)

This is opposite to what was reported by Westmacott (2017) in her research study of English language students in Chile. These students preferred indirect feedback as “it prompts deeper cognitive processing and learning” (p.17). These Chilean students could also represent the ‘conscientious consumers’ of Higgins et., al., (2010) but not the Pakistani students of our sample who were, the majority anyway, more interested in just finishing the task for getting the grade. The frequency of using phrases like ‘waste of time and energy’ in relation to feedback related activities revealed their beliefs about the worth of engaging with feedback. The views of these student-teachers have implications for future processes of teaching and learning at the institutions of higher learning as they will be shaping the academic experiences of our future generation.

Two alternative forms of direct feedback suggested by students were the ‘Supervised preparation of assignments for assessment’ and ‘Help centers.’

A more helpful approach for students is that instead of giving feedback, no matter written or oral, Instructors should hold special sessions where students could work directly on their assignments for assessment under their constant supervision, just like teaching how to solve arithmetic or mathematics problems, Instructors should be present to constantly guide each student, individually through their assignment (S2).

Our university should provide Help Centers as part of Student Support Services where students could seek help for their assignment/ feedback related activities from professional editors. This would also ease the burden of our regular Instructors. (S2)

The above suggestions were analogous to advocating ‘assessment-driven teaching’ with a lot of handholding. It was not difficult to see that students were missing the boat on enhancing their personal capacities for improving their learning outcomes through their own efforts. It re-affirmed our earlier observation that students in our sample were not conscientious but rational consumers who wanted to maximize their gains while minimizing their pains.

Individual vs. group feedback

Individual feedback, in whatever form, was the preferred choice of all students.

It is less hurtful; in fact it is better to have ones shortcomings thrown in their face privately than be humiliated in the presence of one’s classmates (S2)

One-on-one feedback is more specific and directly relevant to individual mistakes (S2)

Qureshi & Vazir (2016), Qureshi (2014) and Qureshi & Vazir (2011) reported similar findings as their students also preferred individual versus group feedback. Similarly, Gallien & Oomen (2008) in their comparative study also stated that students who received individual feedback were more satisfied than their counterparts who received collective feedback.

Conclusion

The focus of our research has been the use and views of students on feedback in higher education. Our research has revealed that students are aware of the importance of feedback in making a difference to the overall quality of their learning, but their usage of it is affected by a host of factors some of which are beyond their personal sphere. Our research has highlighted the complexities of the context in which formative feedback is given and taken. The diversity of learners’ linguistic background is an important context in which feedback usage is embedded; how much of students’ potential is lost because of the differences between the language of higher learning and that of their daily living is not only a concern for linguists but also for other social science disciplines concerned with knowledge creation, acquisition and transmission.

To the best of our knowledge, no research based evidence is available to vouch for formative assessment having a positive or negative impact on students’ learning in Pakistan. What's more is that the dominant mode of assessment is still summative at almost all levels of education. Our research has also revealed that students believe in just completing the task in hand rather than ‘wasting’ time on ‘unproductive pursuit of improving the invisible future learning’. For that reason and in light of our research, we conclude that the Higher Education Commission of Pakistan’s push, implicitly and explicitly, for formative assessment being better than summative may be premature. We need more research on teaching and learning in Higher Education Institutions before finalizing any policy or action plan in this direction.

Acknowledgments

We are thankful to our students who participated in this research. Without them the study would not have been possible. We also thank our colleagues who refined our thoughts through informal discussions of the conceptual framework and suggestions for improving the write up.

References

- Akkuzu, N. (2014). The Role of Different Types of Feedback in the Reciprocal Interaction of Teaching

- Performance and Self-efficacy Belief. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(3):37-66

- Black, P. & William, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning, Assessment in Education, vol. 5, no.

- 1, pp. 7-74.

- Black, P., Harrison, C., Lee, C., Marshall, B., & Wiliam, D. (2004). Working inside the black box:

- Assessment for learning in the classroom. Phi delta kappan, 86(1), 8-21.

- Black, P., & William, D. (2003). ‘In praise of educational research’: Formative assessment. British

- Educational Research Journal, 29(5), 623-637.

- Cauley, M. C., & McMillan, J. H. (2010). FA techniques to support student motivation and achievement

- Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83(1), 1–6.

- Clark, Ian (2012). Formative Assessment: Assessment is for Self-regulated Learning. Educational

- Psychology Review, 24:205–249 DOI 10.1007/s10648-011-9191-6

- Clark, I. (2011). Formative Assessment: Policy, Perspectives and Practice. .Florida Journal of

- Educational Administration & Policy, 4(2), 158-180.

- Coffey, J.E., Hammer, D., Levin, D.M., and Grant, T. (2011). The Missing Disciplinary Substance of

- Formative Assessment. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, Vol. 48. No. 10: pp.1109-1136

- Cookson, C. (2016): Voices from the East and West: congruence on the primary purpose of tutor

- feedback in higher education, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, DOI: 10.1080/02602938.2016.1236184

- Edeiken-Cooperman, N., & Berenato, C. L. (2014). Students' Perceptions of Electronic Feedback as an

- Alternative to Handwritten Feedback: One University's Inquiry. Journal of Education and Learning, 3(1), 79.

- Fook, C. Y., & Sidhu, G. K. (2010). Authentic assessment and pedagogical strategies in higher

- education. Journal of Social Sciences, 6(2), 153-161.

- Forsythe, A., & Johnson, S. (2017). Thanks, but no-thanks for the feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in

- Higher Education, 42(6), 850-859. DOI:

- Gallien. T., and Oomen, J. (2008). Personalized Versus Collective Instructor Feedback in the Online

- Course room: Does Type of Feedback Affect Student Satisfaction, Academic Performance and Perceived Connectedness With the Instructor. International Journal on E-Learning. 7(3), 463-476

- Glasson, T. (2009 ). Improving Student Achievement: A Practical Guide to Assessment for Learning.

- Curriculum Corporation, US

- Harlen, W. (2006). On the relationship between assessment for formative and summative

- purposes. Assessment and learning, 2, 95-110.

- Harlen, W. (2005). Teachers' summative practices and assessment for learning; tensions and

- synergies. Curriculum Journal, 16(2), 207-223.

- Hattie, J.A. (2012). Visible Learning for Teachers: Maximizing Impact on Learning. Routledge, .

- Hattie, J.A., and Timperley, H. (2007). The Power of Feedback. Review of Educational Research,

- 77(1):81–112 DOI: 10.3102/003465430298487

- Hattie, J.A. (1987). Identifying the salient facets of a model of student learning: a synthesis of meta-

- analyses, International Journal of Educational Research, vol. 11:187-212.

- Haroldson, Rachelle Ann. (2012). Student perceptions of formative assessment in the chemistry

- classroom. Retrieved from the University of Minnesota Digital Conservancy, http://purl.umn.edu/131744.

- Harshman, J., & Yezierski, E. (2015). Guiding teaching with assessments: high school chemistry

- teachers’ use of data-driven inquiry. Chemistry Education Research and Practice, 16(1), 93-103.

- Hemingway, A. P. (2011). How Students’ Gratitude for Feedback Can Identify the Right Attitude for

- Success:Disciplined Optimism. Perspectives: Teaching Legal Research and Writing, 19(3), 170

- Higgins, R., Hartley, P., and Skelton, A. (2002). The Conscientious Consumer: reconsidering the role of

- assessment feedback in student learning. Studies in Higher Education, 27(1): 53-64 DOI: 10.1080/0307507012009936 8

- Hill, R. (2016). Locus of Control, Academic Achievement, and Discipline Referrals. Murray State

- Theses and Dissertations. Paper 1

- Isabwe, G. M. N. (2012, June). Investigating the usability of iPad mobile tablet in formative assessment

- of a mathematics course. In Information Society (i-Society), 2012 International Conference on (pp. 39-44). IEEE.

- Jackson, M., & Marks, L. (2015). Improving the effectiveness of feedback by use of assessed reflections

- and withholding of grades. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, (ahead-of-print), 1-16.

- Kennedy, K. J., Chan, J. K. S., Fok, P. K., & Yu, W. M. (2008). Forms of assessment and their potential

- for enhancing learning: Conceptual and cultural issues. Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 7(3), 197.

- Limniou, M., & Smith, M. (2014). The role of feedback in e-assessments for engineering

- education. Education and Information Technologies, 19(1), 209-225.

- Lizzio, Alf & Wilson, Keithia (2008). Feedback on assessment: students’ perceptions of quality and

- effectiveness. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 33(3):263-275,

- DOI: 10.1080/02602930701292548

- Ludvigsen, K., Krumsvik, R., & Furnes, B. (2015). Creating formative feedback spaces in large

- lectures. Computers & Education, 88, 48-63.

- Lysaght, Z. (2015). Assessment for Learning and for Self-Regulation. The International Journal of

- Emotional Education, Volume 7, Number1:pp 20-34

- Minstrell, J., Anderson, R., and Li, M. (2011). Building on Learner Thinking: A Framework for

- Assessment in Instruction. Commissioned paper for the Committee on Highly Successful STEM Schools or Programs for K-12 STEM Education: Workshop, May 10-11, 2011

- Mulliner & Tucker (2017) Feedback on feedback practice: perceptions of students and academics,

- Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 42:2, 266-288, DOI:

- Murphy, C., and Cornell, J. (2010). Student perceptions of feedback: seeking a

- coherent flow Practitioner Research in Higher Education, 4 (1):41-51

- Price, M., Handley, K., Millar, J., and O’Donovan, B. (2010). Feedback: all that effort, but what is the

- effect? Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 35(3):277–289

- Qureshi, R. (2014). Reflections on the implications of globalization of education for research supervision

- . Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, published online: 4-Sep-2014. pp. 546-550. DOI: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.05.095

- Qureshi, R., and Vazir, N. (2016). Pedagogy of Research Supervision Pedagogy: A Constructivist Model.

- Research in Pedagogy, Vol. 6, No. 2, Year 2016, pp. 95‐110.

- Qureshi, R., Zahoor, M., and Zahoor, M. (2017). Assessment drives student learning: Evidence

- From Pakistan. Research in Pedagogy, Vol.7, No. 6, pp. 122-33.

- Roy, J. (2015). The Implementation of Feedback in the English Classes of Bengali Medium

- Schools. Global Journal of Human-Social Science Research, 15(7).

- Saltmarsh, D., & Saltmarsh, S. (2008). Has anyone read the reading? Using assessment to promote

- academic literacies and learning cultures. Teaching in Higher Education, 13(6), 621-632.

- Sanchez, H. S., & Dunworth, K. (2015). Issues and agency: postgraduate student and tutor experiences

- with written feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 40(3), 456-470.

- Searle. M. (2013). Causes & Cures in the Classroom: Getting to the Root of Academic and .Behavior

- problems. ASCD:US

- Shute, V. J. (2007). Focus on Formative Feedback. Research Report. RR-07-11. Educational Testing

- Service. Princeton:NJ

- Tay, H. Y. (2015). Setting formative assessments in real-world contexts to facilitate self-regulated

- learning. Educational Research for Policy and Practice,14(2), 169-187.

- Vazir, N., and Qureshi, R. (2011). How to teach the art of ‘doing’ research: Lessons learnt from teacher

- Education program in Pakistan, in, Teaching and Learning in Diverse Contexts: Issues and Approaches, (Editors), Ambigapathy Pandian, Shaik Abdul Malik Mohamed Ismail and Toh Chwee Hiang, School of Languages, Literacies and Translation: Universiti Sains Malaysia

- Wang, S.L., and Wu, P.Y. (2008). The role of feedback and self-efficacy on web-based learning: The

- social cognitive perspective. Computers & Education 51:1589–1598

- Westmacott, A. (2017). Direct vs. Indirect Written Corrective Feedback: Student Perceptions. Íkala,

- revista de lenguaje y cultura, 22(1), 17-32.

- Yorke, M. (2003). Formative assessment in higher education: Moves towards theory and the enhancement

- of pedagogic practice. Higher Education 45: 477–501

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 October 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-030-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

31

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1026

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Qureshi, R., Zahoor, M., & Zahoor, M. (2017). Does Formative Assessment Help? Students’ Perspective On ‘Feedback’ From Pakistan. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2017: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 31. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 487-501). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.10.47