Abstract

Puberty is an important element of sex education in the European and global context. Puberty is a normal feature of human development and encompasses a number of changes that affect children and their environment. Children need to be prepared for puberty, relevant changes and other aspects associated with this stage of life in a timely and appropriate manner. Children should acquire the necessary knowledge about puberty and should communicate about puberty before its onset. The prepubescent period is identified as the middle school age and relates to children in lower elementary school. Communication about puberty should be based around the family, but there is no guarantee that the child will acquire subjectively and socially desirable knowledge, adequate attitudes and behaviour. The role of the school is to provide information about puberty, basic attitudes and ways of decision-making. Parents and teachers often have barriers to communication about puberty, which result from their unpreparedness due to life experience. The present paper focuses on whether there is any communication about puberty among middle-school-aged children, on ways that they perceive puberty, what they think about it, and whether friends are a source of information about puberty. The paper is a description of a research questionnaire applied in the Czech Republic and China. It describes whether and how middle-school-aged children communicate about puberty. The present research study was carried out at the Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc (Czech Republic) and was a basis for a follow-up research project (IGA_PdF_2017_006), in which communication about puberty in Sweden is currently investigated.

Keywords: Pubertyeducationcommunicationrisk eliminationresearch

Introduction

Puberty is an important element of sex education in the European dimension (Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe, 2010), as well as the global dimension (International Planned Parenthood Federation). It is a usual manifestation of human development, a life stage with a number of changes that influence all individuals and their environment. Children need to be prepared for puberty on time and in an appropriate manner; they need to be prepared for all changes, relations and contexts associated with this stage of life. Children should acquire the necessary knowledge about puberty before its onset. At the same time, they should begin to communicate about puberty. That is, during the prepubescent period in lower elementary school. This is a period of between 8/9 and 11/12 years of age, which is identified as middle school age (Vágnerová, 2000). A middle-school-aged child is capable of adopting a communication style depending on whether he or she communicates with adults or children, at school or at home, etc.

When considering communication, the first aspect to be analysed is the meaning of direct communication between people via speech and writing. Generally, people use verbal and non-verbal means of communication; it is also logical that communication via visual media cannot be ignored. This type of communication is referred to as visual communication. In terms of communication considered in the present paper, it takes place between middle-school-aged children and is of an interpersonal nature.

Communication about puberty is based around the family. However, there is no guarantee that children will acquire subjectively and socially desirable knowledge, adequate attitudes and behaviour in the family. The school is supposed to provide knowledge about puberty, basic attitudes, and ways of decision-making. Parents and teachers often have barriers to communication with their children about puberty. These barriers result from personal unpreparedness due to their life experience (Štěrbová, Rašková, 2014).

The paper provides answers to the following questions: Do middle-school-aged children communicate about puberty? How do they perceive puberty? How do they reflect on their own level of awareness about puberty? Do they consider their friends to be a source of information about puberty? The article is a description of a questionnaire survey performed in the Czech Republic and China. The topic of communication about puberty among middle-school-aged children is contextually related to the authors’ previous empirical research. The purpose of the previous research study was to verify the cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty among lower elementary school students. The study focused on mutual communication about puberty between lower elementary school students, their teachers and families. The present paper describes a single aspect, which is a part of a wider research context. The paper focuses on the questions that relate to communication about puberty among middle-school-aged children. The text describes a questionnaire survey, which was carried out in the Czech Republic and China in the context of a project (IGA_PdF_2015_007) performed at the Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc. This research project is followed by another initiative, which is currently implemented at the Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc (IGA_PdF_2017), headed by the principal investigator doc. Miluše Rašková, Ph.D. The follow-up project systematically addresses the issue of puberty in Sweden. The present paper does not include the results of the questionnaire survey from Sweden because the implementation phase is still in progress (data collection, coding and data processing).

Respondents, research methodology, data collection and data analysis

The investigation of communication about puberty among middle-school-aged children was carried out using a non-standardized questionnaire. The items of the questionnaire were aimed at identifying the opinions about mutual communication about puberty between lower elementary school students, their teachers and the family. The questionnaire items (numbered 10-21) followed the test items (numbered 1-9), which tested the level of knowledge about puberty (Rašková, Provázková Stolinská, 2015; Rašková, Provázková Stolinská, Vavrdová, 2015). The questionnaire items were identified as Part B and were introduced by the following question ‘Who do you talk to about puberty?’ The items were classified according to their content into questions about the source of information about puberty (i.e. from whom or from where students get information), and its frequency or method of communication (i.e. how often, what intensity, what obstacles etc.) The questionnaire items included scaled, closed, and semi-closed questions. The Czech version of the text was proofread and translated to English and also to Chinese by a fellow Chinese doctoral student for the purposes of data collection in China.

In the Czech Republic, the questionnaire survey included a total of 120 students from grade 4 and 5 of elementary schools; in terms of gender the sample was balanced. In China, the questionnaire survey included 135 students of the same age group and gender distribution. The respondents were middle-school-aged children (9-12 years of age). The research data were analysed by means of descriptive statistics. Statistical significance of the differences between the results from individual countries (Czech Republic, China, Sweden) will be examined after the data from Sweden are obtained.

In the questionnaires, the students indicated the intensity of information sources, i.e. from whom or from where they get information about puberty, on a scale never – rarely – sometimes – often – very often. Friends and classmates were included among these sources. In questionnaire items 17 and 18 the respondents expressed their opinions about the intensity of mutual communication about puberty, and about obtaining new information about puberty from friends on a scale never – rarely – sometimes – often – very often. In questionnaire items 20 and 21 the respondents commented on their own perception of puberty and the level of their own awareness about puberty.

Partial results and discussion

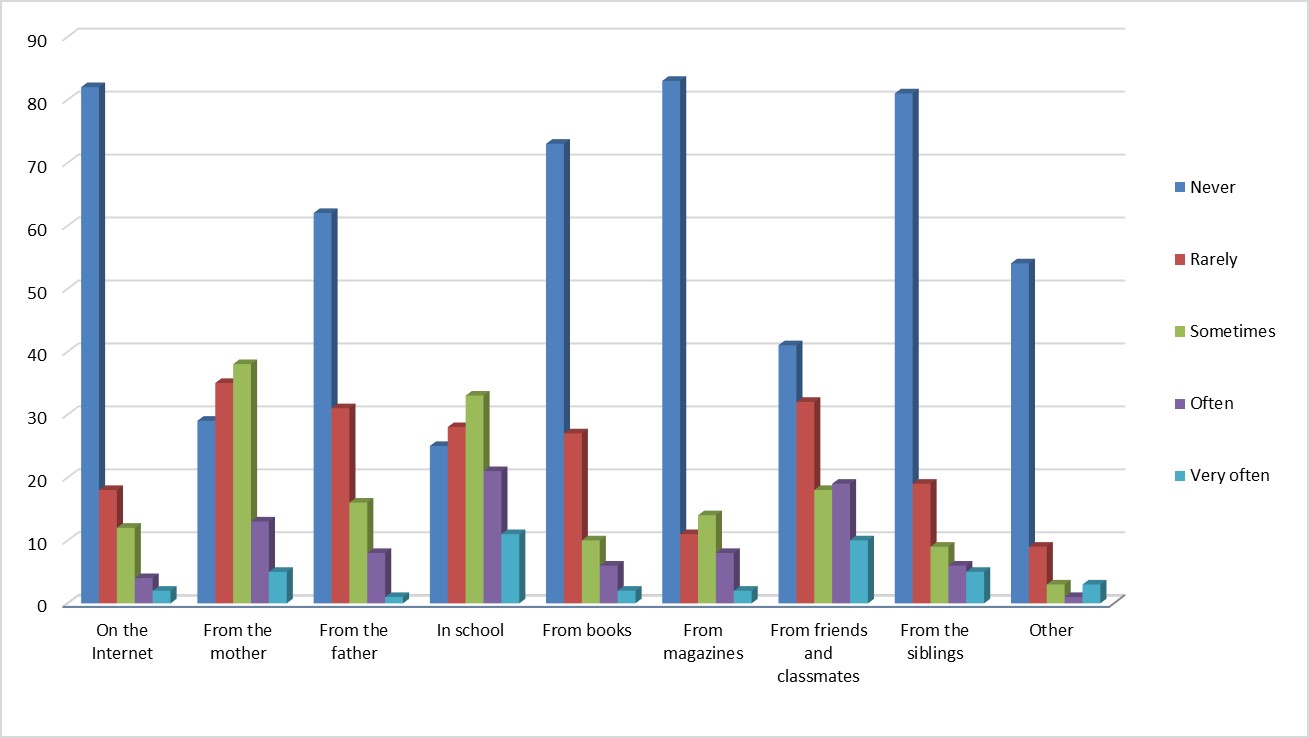

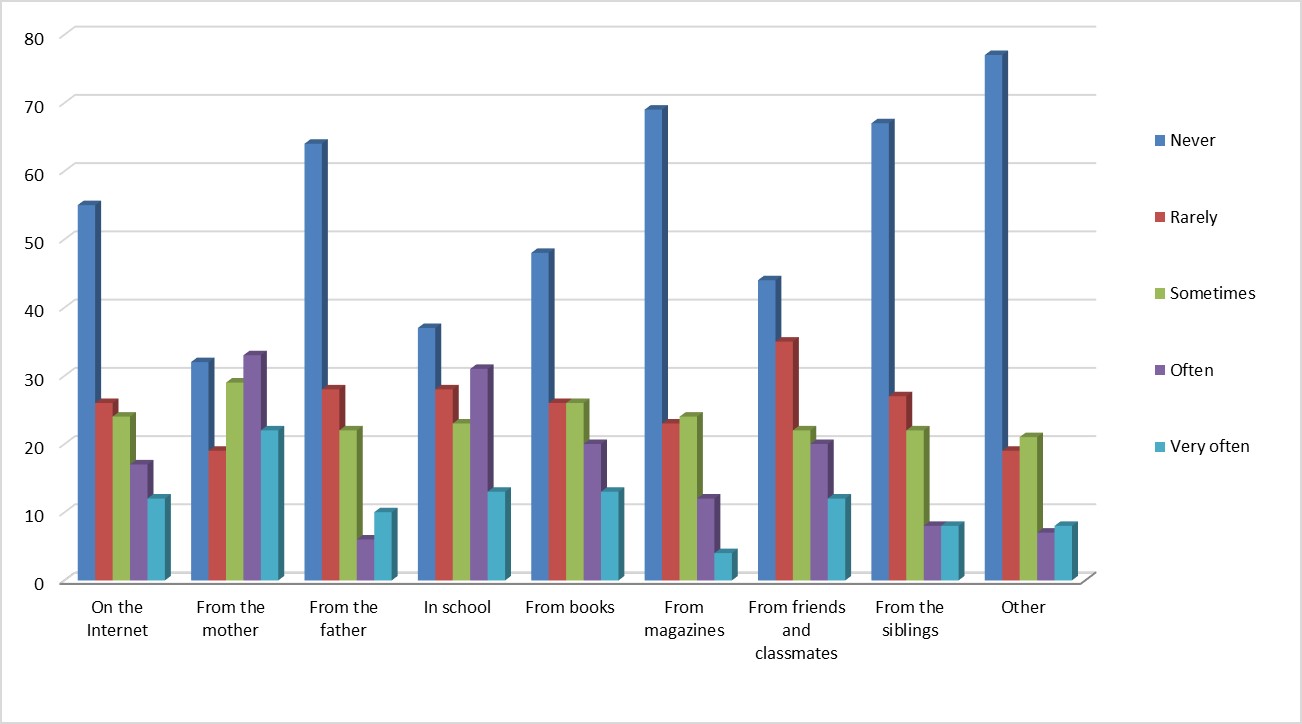

Communication about puberty among middle-school-aged children and relevant sources of verbal and visual information are shown in the figures below. Verbal sources include friends, classmates, mothers, fathers, siblings and teachers. Visual sources include the Internet, books, and magazines. The role of friends and classmates as sources of information about puberty is shown in figures

The distribution of the sources of information about puberty is shown in Figures 1A and 1B above. According to the respondents, friends and classmates are more frequent sources of information about puberty compared with visual sources. Mothers, teachers, friends and classmates reach a low negative score in terms of verbal communication in comparison with other sources. The family, which appears to be the primary source of information about puberty, shows a difference between mothers and fathers. Parents communicate with children about puberty sometimes, rarely or never. The responses suggest that fathers, unlike mothers, do not communicate with children about puberty at all. The role of mothers in providing information about puberty is higher in China. Siblings are sources of information rarely, sometimes or never. In China, unlike in the Czech Republic, the most frequent sources are teachers, mothers, and visual sources (Internet, books, magazines and others).

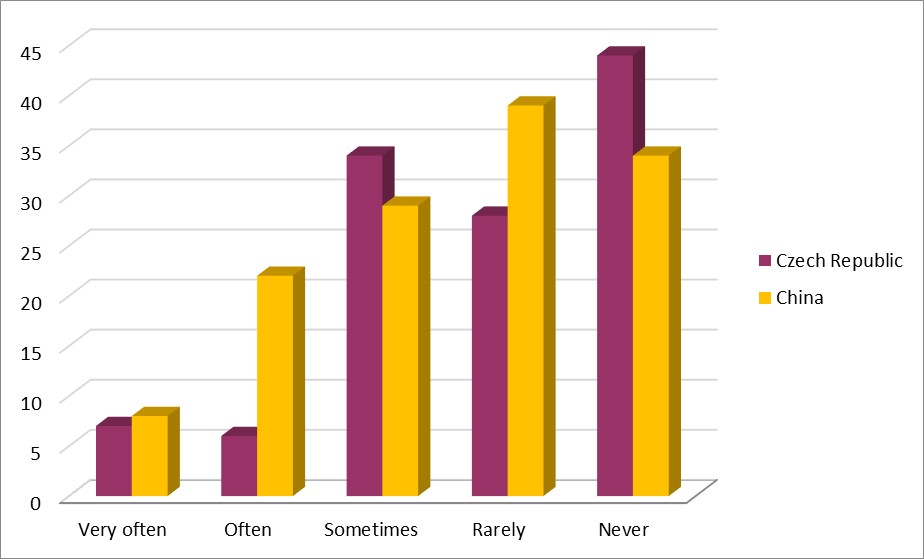

The intensity of communication about puberty among students as reflected by students themselves is shown in Figure

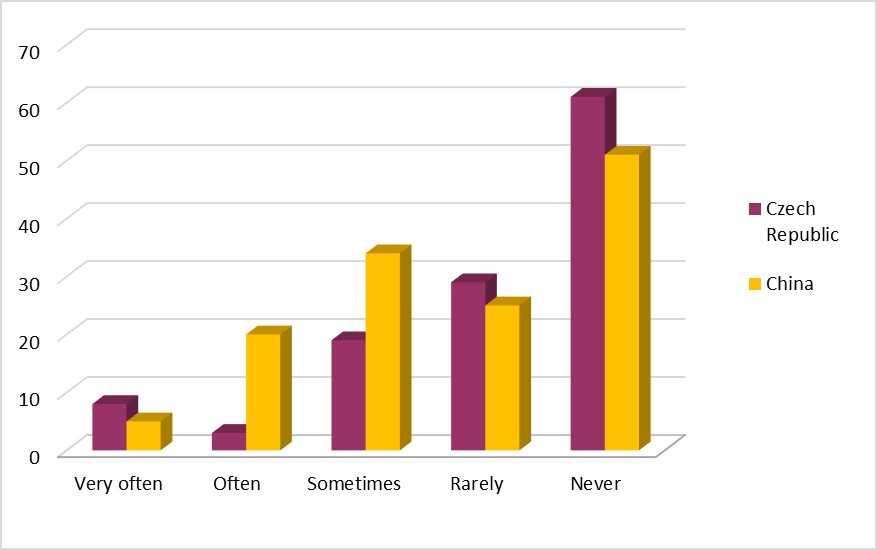

The responses to whether the participants learn some new information about puberty from their friends and classmates are shown in Figure

Czech Republic (p = 120); China (p=135)

Figure

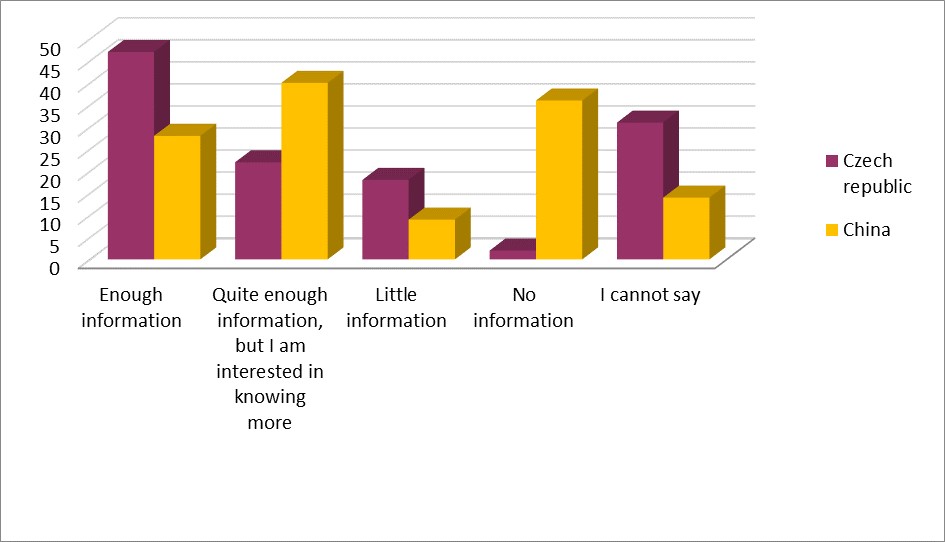

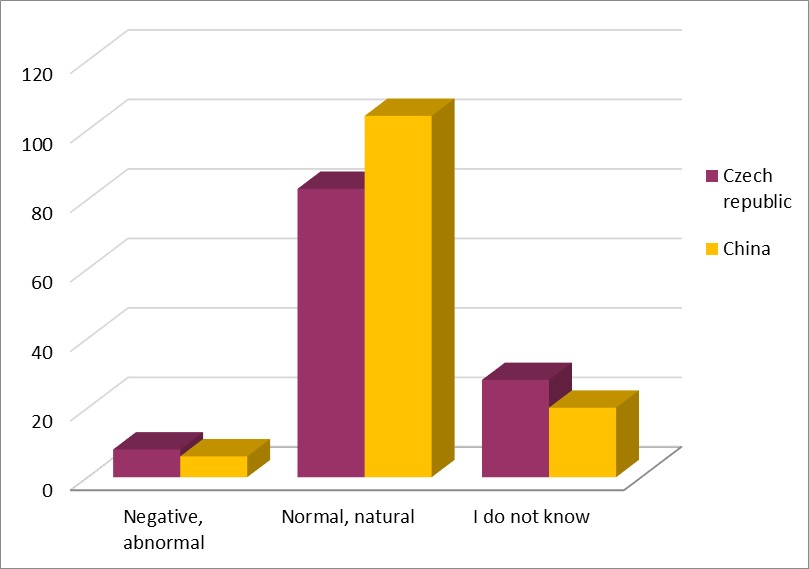

The findings concerning students’ opinions about how they perceive puberty are presented in Figure

Czech Republic (p = 120); China (p=135)

Most of the responses of both Czech and Chinese students suggest that they perceive puberty as a normal and natural phenomenon in their lives. This finding becomes an important prerequisite for communication about puberty in a broader context.

The following statements summarize the preliminary part of the research focusing on communication about puberty among middle-school-aged children:

In the field of verbal communication, the sources of information about puberty include friends and classmates, mothers and teachers; these sources of information appear to be more significant than visual sources;

If students communicate about puberty, the do so sometimes or rarely;

Students perceive puberty as a normal and natural phenomenon;

If students are able to reflect on their information on puberty, they believe the information they have is sufficient but are interested in learning more.

Discussion

Middle-school-aged children in the role of classmates, peers and friends share life experiences and face problems in their peer groups. The influence of the peer group is significant for a middle-school-aged child in the context of gradual socialization. In this age, children communicate in different ways. Various communication styles are related to social experience and development of thinking. Children have a specific way of communication (predominance of slang, popularity of interjections, simplification of speech, noisy speech, non-verbal communication). As far as communication about puberty is concerned, children need to acquire not only a large body of knowledge, but also develop adequate attitudes and behaviours.

As suggested by the authors’ own teaching experience, puberty is an imminent issue for children. Children are aware of a number of fundamental changes, but they do not have a comprehensive idea about biological and psychosocial changes and their importance for the future. From a students’ perspective, biological aspects and their significance for future reproductive life are not associated with other changes. They mostly believe that puberty is reflected in psychosocial changes, as confirmed by various research studies.

Friends and classmates cannot play a priority role in the formation of knowledge or development of adequate attitudes and behaviours. For this reason, it is desirable for children to communicate about puberty with teachers and primarily with their parents. Teachers may also have some personal barriers to communication about puberty with children, but in terms of their teaching expertise and qualification, they should have the knowledge concerning practical application of teaching materials. Teachers provide everything necessary for the process of education, taking into account children’s educational and psychological specifics, humane approaches and ethical principles. School-based communication is influenced and sometimes limited by a variety of different circumstances. The main actor in educational communication is the teacher. First of all, the teacher determines the intention and time of communication activity. In the context of modern education, there has been a shift in the field of teacher-student communication in the sense that students can now freely express their own requirements to the teacher and provide feedback on the teacher’s response (Stolinská, 2009). This can be considered a prerequisite for accepting a partner status between the two actors of the educational process, which can remove the barriers to communication about puberty.

Conclusion

Regarding the fact that children perceive puberty as a normal and natural phenomenon and express their interest in learning more, it is desirable for communication to take place especially in the family and school. Friends and classmates are not competent sources of information because they do not guarantee the provision of relevant knowledge. Friends and classmates do not understand puberty in the context of all changes related to this stage of life. The task of the school is not only to build knowledge about puberty, but also to lay the foundations for attitudes and decision-making. The teacher should be able to communicate about puberty with his/her students despite any pitfalls resulting from personal unpreparedness. The teacher should never be helpless in communication about puberty with children, which might happen to parents. Communicating about puberty in the family should be a natural part of family life. If, for various reasons, the family does not communicate with the child about puberty, mothers and fathers do not take their primary roles, the school and the teacher should substitute the family and take the educational function.

In terms of school-based education in the Czech Republic, the concept and content of puberty education is defined in a state-level curricular document (FEP EE). The school level is represented by school educational programmes (SEPs), according to which education is specifically delivered in schools. The issue of puberty in lower elementary school is a part of Health Education. The teaching goals of Health Education, including the issue of puberty, are fulfilled through all subjects in lower elementary school. The teachers should be professionally and educationally prepared to teach about puberty. The system of education in China has changed dramatically in the recent period due to the introduction of a new subject – Sex Education. Sex Education, including puberty issues, began to be taught in some Chinese schools mainly in Beijing and Shanghai, and mandatory courses have even been introduced in some Chinese universities. In the traditional Chinese society, where sex and sex education is usually a taboo topic, this new school subject has triggered a heated debate. Some Chinese experts and a large part of the lay community claim that it is unnecessary to deliver sex education at the age of six years, i.e. in the first grade of elementary school. Moreover, the new experimental textbooks of Sex Education are thought to be very explicit. A large number of various reactions were presented on the Internet and through press. However, the Chinese Ministry of Education argues that sex education is the best way of protecting children. Apart from parents’ and especially grandparents’ criticism, who still have a strong influence on children’s upbringing, schools also fight a lack of experienced teachers and experts in sex education.

The partial results concerning teacher-student communication about puberty and particularly other research activities of the authors suggest that education about puberty should be implemented in lower elementary school. At the same time, the authors advocate a need for continued teacher training and parent training in sex education with respect to the issue of puberty. Children need and expect adequate and satisfactory answers to their questions. Lower elementary school teachers should have professional qualification and be willing to communicate about puberty with children in a comprehensible manner adequate to their age.

The present research study was carried out at the Faculty of Education, Palacký University in Olomouc (Czech Republic) and was a basis for a follow-up research project (IGA_PdF_2017_006), in which communication about puberty in Sweden is currently investigated.

References

- International Planned Parenthood Federation. b. (n.d.) Comprehensive sexuality education. Retrieved from: <http://www.ippf.org/our-work/what-we-do/adolescents/education>

- Rašková, Miluše and Dominika Provázková Stolinská (2015). Cognitive and informative level of knowledge about puberty of Czech elementary school students. SGEM. Bulgaria.

- Rašková, Miluše and Dominika Provázková Stolinská (2015). Puberty as the concept of pedagogical theory and practice. IAC-TLEI. Vienna.

- Rašková, Miluše, Provázková Stolinská, Dominika and Alena Vavrdová (2015). Educational premises of puberty at primary school. ICLEL. Olomouc.

- Rámcový vzdělávací program pro základní vzdělávání. [on-line] Retrieved from: http://www.msmt.cz/vzdelavani/zakladni-vzdelavani/upraveny-ramcovy-vzdelavaci-program-pro-zakladni-vzdelavani

- Stolinská, Dominika (2009). Efektivita interakce učitel – žák na dnešních školách. Media4U Magazine [online]. No. 1, p. 64-69. Retrieved from: <http://www.media4u.cz>. ISSN 1214-918.

- Štěrbová, Dana and Miluše Rašková et al (2014). The Specifics of Communication in Relation to Sexuality I: Helping Professions in Relation to Sexuality, Including Persons with Intellectual Disabilities. Olomouc: Palacký University. ISBN 978-80-244-4444-4. 161 p.

- Vágnerová, Marie (2000). Vývojová psychologie. Dětství, dospělost, stáří. Praha: Portál. 522 p. ISBN 80-7178-308-0.

- WHO Regional Office for Europe and BZgA. (2010). Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe. Retrieved from: <http://www.bzga-whocc.de/?uid=20c71afcb419f260c6afd10b684768f5&id=home>

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

16 October 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-030-3

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

31

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-1026

Subjects

Education, educational psychology, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Rašková, M., & Stolinská, D. P. (2017). Communication About Puberty Among Middle-School-Aged Children. In Z. Bekirogullari, M. Y. Minas, & R. X. Thambusamy (Eds.), ICEEPSY 2017: Education and Educational Psychology, vol 31. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 194-202). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.10.18