Abstract

As a presence in human life sacred art can act through similat forms of expression and reception in different moments of time and places. Humanistic education through sacred art can convey, through different creative manifestations, those ethical and aesthetical values which can transform the (restorers’) works of art into landmarks based on sublimation into models of self-realization in several fields. This paper presents some visual and synchrectic examples which illustrate the specific nature of the ethical, aesthetic and heritage aspects of some artistic landamarks in the Romanian and neighbourning Orthodox context of sacred art: motherly love and devotion, child devotion, student-teacher relationship and, last but not least, personal self-realization and cultural awareness. The knowledge of, exhibition, conservation and restauration as well as the emphasis on some (hidden) aspects of sacred art objects can contribute to their appreciation; in particular, through them young people can connect to their own or other spiritual and material, old and updated tradition(s).

Keywords: Sacred arteducational landmarkshumanistic perspectiveethicalaesthetic and heritage aspectsRomanian Christian

Introduction

Present in time as long as the human species, sacred art is thousands of years old; not exclusively a special section of artistic and religious expression, sometimes polarized in space and time, sacred art represents a substantial resource of aesthetic values. Sacred art can supply a solid ethical background and impact. Art in the religious context is called to act as ‘theology in colours’/words/sounds and to educate, as an inspiration in self-development and heritage-awareness.

Problem Statement

Sacred art educates moral values

The role of sacred art rests in its core function of conveying traditional religious, moral values, with a potential to change education in humanities as well as visual education today. This role should not be neglected. The moral values of Christianity as a personal faith and a community belief are transferred into the everyday life of the community by artistic means and practices. In what is commonly a long-time effort, this involves, among other forms, (re)creative work, data collecting and archiving (Anastasiu et al., 1976).

Also, the potential of synchretic acts as liturgy has been strong enough to help preserve the identity of smaller or emigre groups (Vascenco, 2003).

Sacred art gives a sense of identity

A person with an artistic background can have stronger convictions and arguments in a world which shows a tendency to relativize values. Icons and murals as well as spiritual verse are called to educate people and give them a sense of belonging to a certain time and place.

Research Questions

The role of sacred art resides in its core function of conveying traditional religous, moral values, with a potential to change education in humanities as well as visual education today. This role should not be neglected. The moral values of Christianity as a person’s faith are transferred into the everyday life of the community by artistic means and practices. This collective effort involves, among other forms, (re)creative work, data collecting and archiving. Also, the potential of synchretic acts as liturgy has been strong enough to help preserve the identity of smaller or expatriate (emigre) groups.

The knowledge and study of the values of Sacred Art can facilitate the infusion of ethical and aesthetical principles which should lead to an appreciation of cultural-religious commodities and to the involvement in their protection, whether they are seen as heritage values or not. The first impression or appearance does not offer conclusive evidence or true answers. Further investigation can reveal hidden phenomena or a complex situation, which need minute work and take time and patience for clarification. An older paiting, hidden by a newer repainting confronts the evasion of tradition (by visual surrogates) with its recuperation (by iconographic restauration). The need for professional restauration, which has been done professionally in Romania cannot be overstated (Anastasiu, et al., 1976).

Then, variations on the same theme offer the subtle performance of plastic nuances within the observance of some iconographic cannons, as can be seen in the art of some ethnic communities (Russian Orthodox Old-Believers, Lipoveni, ’Lipovans`) (Fedotov, 1991/1935; Melnikov, 2013)..

Purpose of the Study

The knowledge and study of the values of Sacred Art can facilitate the infusion of ethical and aesthetical principles which should lead to an appreciation of cultural-religious commodities and to the involvement in their protection, whether they are seen as heritage values or not.

Is sacred art still relevant for the young generations today? How is new artwork seen as compared to heritage values? What kind of ethical and aesthetical landmarks can one find in sacred art and humanist education? These questions have been raised by the authors, who, as educators, are in a position to ask them with every new generation of students.

Icon restauration and spiritual verse

This paper presents some icons and murals from some Romanian sources on which the authors have worked as well as some evidence from the spiritual and artistic life of a relatively-closed Christian Orthodox community church in Northern Romania (Melnikov, 2013). The mother-child love comes from the icon of Theotokos with the infant Jesus Christ. Various sacred images displayed in the church in the area reserved for women strenghten the same virtues of faith, hope and love guided by and guiding divine wisdom and devotion. While some of these images were made by the authors and their students, others were shown in connection to the practice of communal prayer.

Research Methods

This paper presents the results of observation carried out over a longer process of work in icon restauration, field work and archiving. Observation, data analysis, (socio) linguistic analysis and documentation have been involved in a complex methodology.

Documentation, research and restauration correlates a set of minute and long-time activities. Their results, which are not always public knowledge, are destined to keep and convey past messages which might otherwise dissapear. Such essential ways (contributing to the development of knowledge) involve many fields of activity and usually take place in anonimity; neither of these fields, scientific, humanistic or artistic, can be considered more favoured or more important, because the diverse material expression of concepts legitimates them by the very concrete evidence to which they constantly relate. This is why without documentation, observation, analysis, comparison, assessment and conservation-restauration any field is bereft spiritually and materially. The human being risks to be left without the necessary, important and multiple landmarks which lat them make progress on the path of knowledge with increased discernment and responsibility. In fact, even if the reference in this paper are concerned with (the need of) sacred art, these landmarks do not target exclusively the faithful or/and people affiliated to iconographical art; they try to attract and raise the visual-artistic-religios-humanist awareness of anyone who sees the work. The following questions are asked in this process: What is a human being’s task? What can one say about the human seed which has been shared with you by a work of art? What do you know and what do you do to keep it alive, in yourself and in the community? While these questions and methods to answer them involve the idea of

Findings

Many genuine values of Romanian national heritage are still unknown, mainly due to historical events. One can discover these values gradually, by combining the research methods of sciences, history, art, sociolinguistics etc. The art history research blends with the current scientific possibilities, especially in the restoration and conservation of cultural and heritage objectives.

Icon restauration

Sacred art features significantly among these Romanian paintings of the 17th-19th centuries. The actual rediscovery of real values, covered by the “matter of time”, can be illustrated by some images of the phases of cleaning a painting on wood and also of an icon and a heritage object in the Orthodox cult (set of photos a-h in Figure

Photos a-b-c-d: Details in the process of cleaning and removing the repainting show the comparative difference from a plastic point of view between the decorative style of Byzantine influence of the original painting of Mother and Child (the end of 17th century), and the naturalistic image of St. Menas, a repainting (end of the 19th century or ear;y 20th century).

Photos c-d: Details of the removing the repainting progressively reveal the initial writings and the image of the icon of Theotokos Hodegitria

Photos e-h: Revealing the initial image (Theotokos Hodegitria) on the 17th century icon, after the removing of the 19th repainting and of other restauration stages. The almost symmetrical gravity of the expression of the faces resonates with the asymmetrical parallelism of the hands on the backround of the red vestments (symbolizing humanity, commitment, love, sacrifice) which covers their blue zones (a symbol of spirituality and celestial dimension). The golden uncreated light in the background is counterpointed by circles of inscriptions, personalized in colours and dimension for Theotokos and Child Jesus Christ. The sobiety of the faces appears as a counterbalance in a symmetrical spirit to the gestual resolution of the hands, which seem smaller, but wholly protective in their rectangular rhythnics. A monolith of a visual expression, the image is rigurous, balanced and harmonius. Eventually, after the contemplation of the icon, a feeling of suspension in internalization lingers and the feeling of material substance is transgressed.

Photos “a- h” (All the photos in this paper (Figures

The Eight Sequences Shown In Figure

Other images of the Theotokos with the infant Jesus (Figures

Religion and ethnic identity

The identity of the relatively-closed community of Russian Christian Old Believers in Romania, known as the Lipovans (

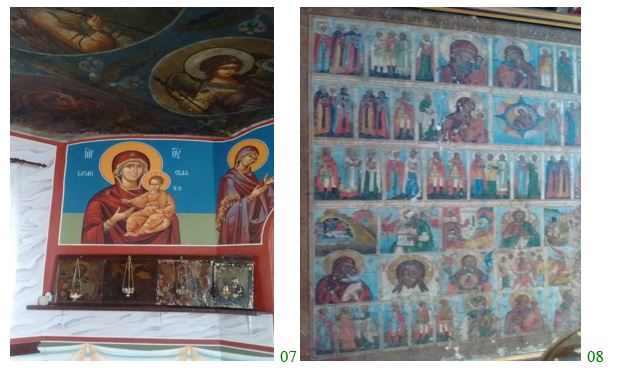

Lipovan iconography shows a preference for some specific representations, such as the forty faces of the Theotokos, shown in Figure 08 above. Part of the traditional and compulsory education of any Lipovan, church-going, knowledge of Slavonic and ritual has created (and exported) a set of basic humanistic values. The strict division of women and men during liturgy in Old-Believers churches - the women enter through the west door and stand exclusively in the pro-nave - is reflected in the specific decorations in this part of the church: Theotokos (Figure 07). Other ‘Lipovan’ icons have lost their masters, but can safely rest in the welcoming Orthodox medium (Figure 06). Others yet are eshibited in musems (Figures

The readings assigned to some icon feasts are accompanied by spiritual verses whose significance cannot be overlooked. Old Believers treasure a traditional Russian form of sacred poetry, the so-called

So, forms of plastic and literary art are vividly present in this strict community which manages to educate their young generation into the essential Christian moral values, as well as into the specific associated art forms.

At the interference between the canon of images, epic context and religious significance, the image of the icon brings together a complex of feelings and information; its mission is to educate, from a spiritual and humanist perspective, any onlooker or believer who discovers its inherent value through their own faith and receptivity towards the simultaneously received spiritual, ethic, aesthetic and heritage messages. In sacred art, these messages are conveyed along as educational and humanist landmarks; they tend to induce the reaching of the essence of being through sublimated forms of expression, which, intn, illustrate the content that individualized them and the harmonious features that brought them together.

Conclusion

The questions the authors asked themselves have generated some observations and suggestions included in this study. The authors have collected data from the field of icon restauration, mural representation and sacred oral literature present in the life and work of a community living in Romania. The fact that young generations today have developed an interest in sacred art, the increasing number of schools of painting, both part of systematic and occasional (summer) education show an interest that has been `exported’ to Europe. Along with traditional arts and crafts, sacred art in Romania - either in the general community and in some local (ethnic) communities holds a special position.

The two aspects presented in the two iconographic situations: the hieratism of Byzantine tradition illustrated by Theotokos Hodegitria and the naturalism of `Lipovan` iconographic representation have as plastic connecting points the rubicond images of Theotokos Orans, which belong to the Orthodox iconographic type; but by excessive visual expression, this frame is naturally overcome, the decorative techniques for showing the veneration of Sacred Persons and the enhancement of visual attraction are evidenced as an artistic option to be used.

The element of hieratism and austerity, of the awareness of the Saviour’s sacrifice, which is bound to follow, the anticipation which informd the grave faces of the icon of Theotokos Hodegitria is paralleled by the element of joyful and serene invocation of divine protection, by the prayer oriented in a gesture to God - in the icon of Theotokos Orans with the Holy Child. In both cases the symbolic elements in the parent-child-divinity communion draw one’s attention to the need and importance of asking and receiving divine protection, either with the feeling of a path taken to basic-reference religious values, or to those situated in its axis, to acceed to the divine from their own depths. The selected visual illustrations, beside their message as heritage values, contain some essential connotations without which human beings cannot find and maintain in time their positive sens of earthly life and their balance to be adopted as beings.

In other words, religiosity expressed here in a Christian Orthodox sense is a component of the human being, irrespective of its degree of exteriorization in a spiritual and material sense; from a theoretical, concrete, dogmatic and aristic perspective, sacred art represents a set of symbolic vehicles for the journey of sharing diverse typologies of religiosity.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the following: the Climăuți community for their persmission to take pictures inside the Church of Saint Sergius of Radonezh on the saint’s feast; the ICEM Tulcea Museum Complex; the Popăuți Monastery, Botoșani and to the Cetăţuia Monastery, Iaşi.

References

- Anastasiu, A., Moagar, P. A., Stoica O., Ionescu, V., Vartic Gh., Cosaceanu P., Fagarasanu, M., Maluchin,E., & Bente T. (1976). Restaurarea - știinta si artă. Bucharest: Muzeul de Artă al Republicii Socialiste România

- Dionisie din Furna. (2000). Erminia picturii byzantine. Bucharest: Editura Sophia.

- Fedotov, G.P. (1991/1935). Stikhi dukhovnye (Russkaia narodnaya vera po dukhovnym stikham). Moscow: Gnozis.

- Melnikov, F.E. (2013). Istoria biserici ortodoxe de rit vechi. Translation by Leonte Ivanov. Bucharest: CRLR Publishers .

- Vascenco, V. (2003). Lipovenii. Studii lingvistice. Bucharest: Editura Academiei.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 July 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-026-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

27

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-893

Subjects

Teacher training, teaching, teaching skills, teaching techniques,moral purpose of education, social purpose of education, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Dominte, G. M., Vraciu, M., Cojocea, B., & Onica, S. (2017). Some Educational Landmarks Of Sacred Art In A Humanistic Perspective. In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Multidimensional Education and Professional Development: Ethical Values, vol 27. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 404-412). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.07.03.48