Abstract

In this paper, we aim to bring into question a subject that has been addressed over the years by many professionals from the field of educational sciences, which consists in adapting the methods of teaching - learning to the educational needs of the student, in particular, those with attention-deficit and hyperactivity disorder. The Custom Intervention Program lies at the core of the inclusive education of the student with ADHD and promotes the idea of a personalized and differentiated teaching method. In the past years, there have been adopted more personalized intervention programs based on behavior change regarding children with ADHD in the school environment, without significant results. Nevertheless, we pored over one that is being used in health psychology. In order to verify the utility of the program, we examined some relevant studies. The originality of our study lies in our own adaptation of the behavior change program based on the INTEGRATED THEORY OF HEALTH BEHAVIOR CHANGE (ITHBC) to the school environment. The methods that we used are the following: observation, interview, investigation of school documents and case study. We concluded that the problem of children with ADHD is linked to the adaptive behavior to the school environment and, therefore, we consider it necessary to use the above mentioned program. Creating a healthy educational environment implies adopting a functional behavior by the students with special educational needs, more precisely, by those with ADHD.

Keywords: Special needsADHDindividual educational plandifferentiated teachinginclusive education

Introduction

In this study, we aim to adapt the teaching and learning methods to the educational needs of students, especially to those who suffer from attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder. In the past years, there have been adopted more personalized intervention programs based on behavior change regarding children with ADHD in the school environment, without significant results. Nevertheless, we pored over one that is being used in health psychology. In order to verify the utility of the program, we examined some relevant studies.

In the following, we will define three important terms, more precisely: special educational needs, inclusive school and attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder.

Special educational needs (SEN) are defined in the Executive Decision n˚ 1251 from 2005, which enumerates a few improvement measures regarding the acts of learning, instruction, compensation, recuperation and special protection of the children/ students/ youngsters with special educational needs from special or inclusive schools: “additional educational needs, complementary to the general objectives of education, adapted to the individual particularities and to those that are characteristic of a deficiency/ disability or disorder/ difficulty in learning or of a different nature, and also a complex assistance (medical, social, educational, etc.)” (Creţu, 2006).

Students with ADHD (attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder) are included in the category of students with special educational needs.

ADHD (attention-deficit/ hyperactivity disorder) is characterized by attention-deficit or/and hyperactivity. There are three types of ADHD: inattentive ADHD, hyperactive-impulsive ADHD and combined ADHD, which exhibits symptoms of both inattentive and hyperactive-impulsive ADHD.

Approximately 80% of the first graders were diagnosed in 2002 with ADHD in the USA, and it was believed that between 30 and 65% of them were likely to have behavioral disorders in adolescence (Cooper and Bilton, 2002, apud Rutter, 2011).

This is, according to Barkley (1997), a mental disorder of the neurodevelopmental type, characterized by an early debut (usually in the first five years of life), a lack of persistence in activities that require cognitive involvement, a tendency to switch from one activity to another, without completing the first one, a disorganized behavior and an excessive activity (Barkley, 2004; Taylor & Larson, 2011).

The inclusive school elevates the act of learning to a general principle and implies a universal belief that any child is capable of learning. All the actors that are involved in education learn, change and transform themselves. In the learning and teaching process, it is fundamental to understand the interactivity of learning and growth. Every participant learns and grows by interacting with others. Thus, not only teachers learn continuously, but also school managers, parents and other members of the community. The concept of inclusive education addresses the individual needs, but offers, at the same time, solutions for collaborative and cooperative learning. The sources of learning can be found in interpersonal relationships and in the permanent experience that the individual has with the objects and with himself/ herself. School is not only the territory of academic knowledge, but also of practical experiences and interpersonal relationships (Crețu, 2006).

Problem Statement

It is well known the fact that, at most times, the class teacher cannot identify a child with ADHD, mainly because any child that has a choleric temperament can be mistakably diagnosed with this mental disorder. Moreover, the teacher will have to learn different ways of engaging the other students and also the parents of the child with ADHD in showing a positive behavior support to the child with this type of disorder.

In Romania, we do not know much about these students. They are usually called children with a difficult behavior. There is no clear distinction between behavioral disorders and ADD/ADHD, and the diagnosis is being made superficially. This is why we believe that it is necessary to elaborate a personalized intervention plan by a team of specialists in science education, psychology and psychiatry.

Furthermore, we consider that it is necessary to create a personalized program, based on behavior change theories, because hyperactivity and attention deficit have an impact on adopting a functional behavior in school environment.

Finally, adopting a personalized program determines a functional behavior not only in the classroom, but also in different situations that the child diagnosed with ADHD encounters daily. Thus, the functional behavior can be generalized.

Research Questions

In this study we want to answer at the next question: Do personalized educational programs have an impact on adopting a functional behavior by the child with ADHD?

Purpose of the Study

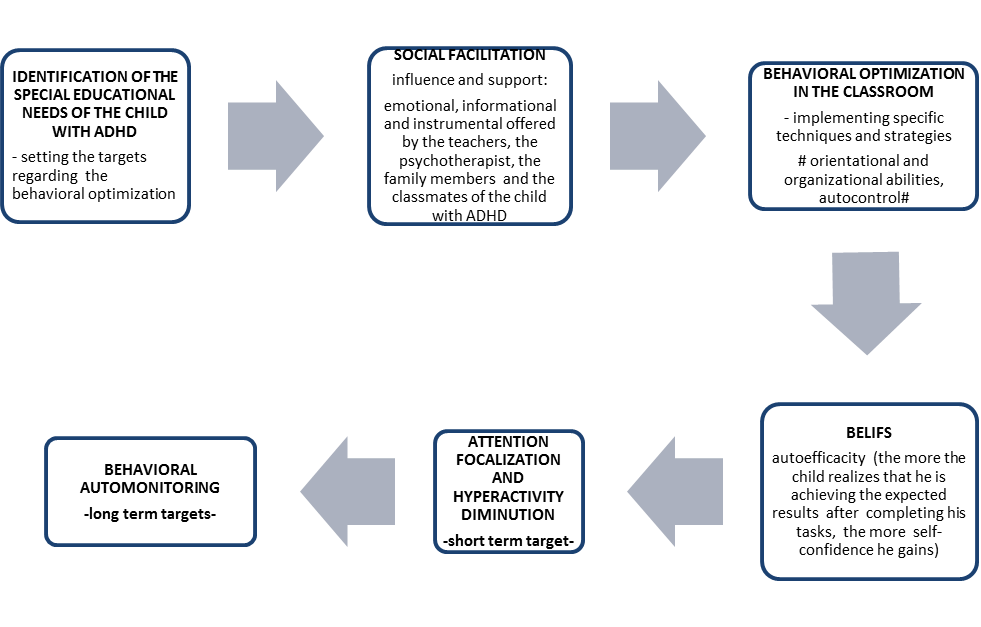

Our purpose is to adapt a behavior change program based on ITHBC (Ryan, 2009) to the educational needs of the student with ADHD. In this paper, we aim to adapt a behavior change program from Health Psychology to school environment, because we consider that it is necessary to create a healthy environment that can determine not only the inclusion of the child with ADHD, but also his/ her adaptation to the challenges that arise in the school environment and, moreover, his/ her adaptation to the everyday challenges.

Therefore, we aim to create personalized educational programs based on the Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) (Ryan, 2009).

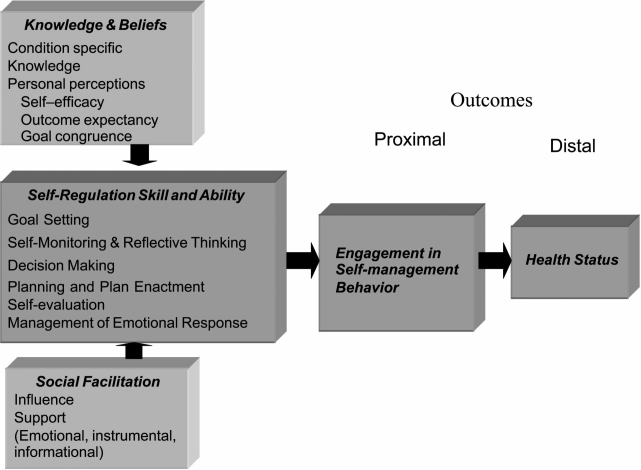

The Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change (ITHBC) (Ryan, 2009) tries to change the patient’s behavior and is oriented toward maintaining a good health. This type of behavior can be improved by promoting knowledge and beliefs, developing self-regulation skills and abilities, and also by consolidating social facilitation. Engaging in self-management behaviors is perceived as a proximal outcome/ short-term outcome, and this, in turn, influences the long-term outcome, namely, the health status. The ITHBC presumes that the change behavior process is dynamic and iterative. Desire and motivation are two preliminary conditions in order to initiate change, and self-reflection facilitates progress. Positive social influences guide a person’s interest toward respecting a number of rules that help maintain change.

According to ITHBC (Ryan, 2009), the persons who want to engage in health maintaining behaviors, which are recommended by the doctor, the persons who have information regarding their illness and want to embrace healthy behaviors, the persons who develop self-regulation skills, oriented toward a good health status, the persons who experience social facilitation, which plays a positive part in encouraging change behavior, based on self-efficiency, hope of resolving the issues and realistic objectives, in the long-term, will improve their health status.

This theory is based especially on self-regulation and social facilitation (Ryan, 2009).

Self-regulation (Ryan, 2005 apud Ryan, 2009), as an educational objective, is the process used in order to change behavior and incorporate activities such as: goal setting, self-monitoring and reflective thinking, decision making, planning and plan enactment, but also self-evaluation and management of emotions occurring with the change.

Social facilitation includes the concepts of social influence, social support and collaboration/ negotiation between individuals, family and professionals (Ryan, 2005 apud Ryan, 2009).

The Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change is based on Bandura's social learning theory (1986) and on the theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991 apud Armitage & Conner, 2001; Ryan, 2009) (Figure

The theory of planned behavior (Ajzen, 1991, apud Armitage & Conner, 2001) suggests that behavior is dependent on someone’s intention to produce the behavior and on attitudes (an individual’s beliefs and values about the outcome), but also on subjective norms (beliefs regarding what other people think the individual should perform or social normative pressure).

Behavior is also determined by the perceived behavioral control of the individual, defined as an individual’s perception about his capacity or feelings of self-efficiency to produce a behavior. This relationship depends usually on the type of relationship and the nature of the situation. Namely, if a person believes that he/she can perform a certain action, he/she will try to accomplish it (Armitage & Conner, 2001).

Bandura, on the other hand, according to Negovan (2010) stresses the importance of observing and modeling other people’s behavior, attitudes and emotional reactions. Observing others and copying someone’s behavior offer information about other types of reactions, their impact and their consequences. This information becomes subsequently a reference point for future actions.

The purpose of social learning is to assimilate a desired behavior, new desired behaviors, new forms and schemes for interpersonal interactions, and, thus, new personality traits. To a large extent, all human learning is social, because it takes place in cultural contexts and is conducted by exemplar models. There is a social learning to a small extent, specialized in creating a connection with reality and the interpsychological values and norms.

In the adapted version of the program, we keep the construct of social facilitation as a key element, which determines:

behavioral optimization in children with ADHD,

development of self-efficacy for learning,

focus of attention on tasks and diminution of distractibility in children with ADHD, by intervening in the environment where the classes take place and by making a collective effort to support the children with ADHD.

SOCIAL FACILITATION is initiated, first of all, by the teacher, the psychotherapist, the support teacher and also by the other students and the parents of the child with ADHD, and can be realized by:

a) paying attention to the way we give instructions, to the words and tone used – clear instructions, complex tasks broken into smaller steps, easy to realize

b) correctly applying psychotherapeutic techniques of behavioral change (ABC behavior model (David, 2012))

c) adapting the space where classes take place – as few distractions as possible

d) giving rewards in accordance with the established plan (The rewards can be verbal, in order to encourage the child to do his/ her tasks.)

e) making sure that the child with ADHD does his/her homework with the help of a parent. As fallows, the child learns mathematical formulas, which are steps for correct problem solving (Figure

Research Methods

After identifying the child with ADHD, the Personalized Intervention Program will be implemented by a team of specialists consisting of: the class teacher and the support teacher (who will implement pedagogic methods adapted to the program’s objectives), a Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy psychotherapist (who will implement behavioral change techniques, which will have an impact on the academic achievement of the student with ADHD). They will try to find the best pedagogical and psychotherapeutic methods in order to engage the other students in the process of behavioral adaptation of the child with ADHD and to adapt the environment and the educational tasks to the needs of the student with ADHD.

Methods

In order to implement this type of personalized plan, we will use different methods: the observation method, the case study method, the interview method and the content analysis method.

The observation method and the case study method will be used to find the support needs and the special educational demands of the child with ADHD. They will be implemented by the class teacher, the support teacher and the psychotherapist.

The interview method will be used by the psychotherapist to find out information that he cannot obtain by using other methods, such as those referring to the behavior of the child with SEN/ ADHD when he does his homework.

The content analysis method will provide information about the school progress before and after the implementation of the program.

Participants

The Personalized Intervention Program addresses schoolchildren, diagnosed with ADHD, who attend a mainstream school.

Findings

According to the authors, this theory became the base for an intervention program for prevention of osteoporosis in women.

The initial testing of the theory showed that the concepts within the theory explain approximately 25% of the variation for a specific health behavior change and up to 45% of the variation when select characteristics of the participants (race/ethnicity and body mass index) are used as moderators (Ryan et al., 2005 apud Ryan, 2009).

Women who were at a high risk for osteoporosis were included in a support group, and they were required to engage in a number of health behaviors, such as consuming an adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D, engaging in easy physical exercises, such as Thai Chi, and also maintaining a body mass index appropriate for their height. The intervention plan was created with the assistance of a computer and with the help of doctors, nurses and the other patients who were included in the group, by talking about their own experience. Consequently, it was possible to set realistic and feasible goals, in the short- and long-term (Ryan et al., 2005 apud Ryan, 2009).

In view of these results, we consider that the students with ADHD can adapt to the challenges that arise in the school environment by implementing an intervention program based on the theory of behavior change. Even though, at first glance, there is no connection between women with osteoporosis and students with ADHD, in both cases, these persons need support for behavior change. Like women with osteoporosis, students with ADHD need to be taught how to self-manage their behavior by giving them the required support.

Conclusion

Unquestionably, ADHD is a complex disorder (which affects more men than women) and there is no simple explanation, despite a significant number of researches, that can isolate its causes (Thapar et al., 2013).

Just a few studies have shown the effects of intervention programs on academic achievements and on behavior change in children with ADHD (Wyman et al., 2010; Pfiffner et al., 2013). There is no study that stresses the importance of creating a team of specialists in behavior change in children with ADHD.

The teacher must understand that, by moving a child with ADHD from a class to another, he does not solve the educational problems of the student and that he must intervene promptly along with the interdisciplinary team in order to support the educational needs of all the students.

The teacher is also responsible for creating a supportive environment for the child with ADHD and encouraging his classmates to help the student with a difficult behavior. Thus, it is essential to initiate social facilitation by influencing and showing emotional, informational and instrumental support.

References

- Armitage, C. J., & Conner, M. (2001). Efficacy of the Theory of Planned Behaviour: a meta-analytic review. The British Journal of Social Psychology / the British Psychological Society, 40, (471–499.

- Barkley, R. A. (1997). Behavioral inhibition, sustained attention, and executive functions: constructing a unifying theory of DAHA/ADHD. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 65–94.

- Barkley, R. A. (2004). Attention – Deficity/Hyperactivity Disorder and Self – Regulation. In R.F. Baumeister, & D. K. Vohs, (Eds.), Handbook of Self-Regulation. Research, Theory, and Applications (pp. 301-323). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Crețu, V. (2006). Incluziunea socială şi şcolară a persoanelor cu handicap strategii şi metode de cercetare. București: Printech Publishing.

- Negovan, V. (2010). Psihologia învăţării - Forme, strategii şi stil. București: Editura Universitară.

- Pfiffner, L. J., Villodas, M., Kaiser, N., Rooney, M., & McBurnett, K. (2013). Educational Outcomes of a Collaborative School–Home Behavioral Intervention for DAHA/ADHD. School Psychology Quarterly : The Official Journal of the Division of School Psychology, American Psychological Association, 28(1), 25–36.

- Rutter, M. (2011). Research review: Child psychiatric diagnosis and classification: concepts, findings, challenges and potential. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 52(6), 647–660.

- Ryan, P. (2009). Integrated Theory of Health Behavior Change. Clinical Nurse Specialist CNS, 23(3), 161–172.

- Taylor, H. E., & Larson, S. (1998). Teaching Children with DAHA/ADHD: What Do Elementary and Middle School Social Studies Teachers Need to Know?. The Social Studies, 89(4), 161–164.

- Thapar, A., Cooper, M., Eyre, O., & Langley, K. (2013). What have we learnt about the causes of DAHA/ADHD?. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 54(1), 3–16.

- Wyman, P. A., Cross, W., Brown, C. H., Yu, Q., Tu, X., & Eberly, S. (2010). Intervention to Strengthen Emotional Self-Regulation in Children with Emerging Mental Health Problems: Proximal Impact on School Behavior. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 38(5), 707–720.

Copyright information

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

About this article

Publication Date

30 July 2017

Article Doi

eBook ISBN

978-1-80296-026-6

Publisher

Future Academy

Volume

27

Print ISBN (optional)

-

Edition Number

1st Edition

Pages

1-893

Subjects

Teacher training, teaching, teaching skills, teaching techniques,moral purpose of education, social purpose of education, counselling psychology

Cite this article as:

Lincă, F. I., & Hrițcu, M. Ș. (2017). Personalized Intervention Program For Children With Special Educational Needs (Adhd). In A. Sandu, T. Ciulei, & A. Frunza (Eds.), Multidimensional Education and Professional Development: Ethical Values, vol 27. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 364-371). Future Academy. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.07.03.44